Report 17 2058 Reportingnz: Building a Reporting Framework Fit for Purpose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary and Recommended Investment Strategy. Investment Outlook

Thirty Four Years of Independent Information and Unbiased Advice on the Australian and NZ Stockmarkets Market Analysis Issue No. 516 www.stockmarket.co.nz June 8, 2015 Inside Market Analysis Nuplex Industries to lift dividend ................................ 2 Neglect Ratings of New Zealand Shares ................... 7 ALS Life Sciences becomes largest division.............. 2 Neglect Ratings of Australian Shares ................ 10, 11 Private Equity firms buys into Cardno ........................ 4 Short Interest in Australian Shares .................... 11, 12 Founder: James R Cornell (B.Com.) Summary and Recommended Investment Strategy. Successful non-resource exporters will continue to benefit significantly from the downturn in the resource sector and the resulting lower Australian dollar exchange rate. Remain fully invested. Investment Outlook. Our Stockmarket Forecasts remain relatively Bearish to Stockmarket Forecasts Neutral and sentiment remains depressed, but it is difficult One-Month One-Year to make a case for a significant stockmarket decline. Australia: 25% (Bearish) 58% (Neutral) Media reports on the Australian Resource sector are New Zealand: 64% (Bullish) 41% (Neutral) depressing, but are an example of Peter Lynch's “penultimate preparedness”. Commodity prices have fallen and new mining developments have been cut back 80-90% . so the media (and investors) are now expecting and “prepared” for commodity prices to fall and mining developments to be cut back! Stockmarkets peak (and subsequently decline significantly) from an environment of excessive optimism New Zealand and over-valuation. The sort of thing that we saw in the NZX 50 Index 1980's Investment and Property boom or the late 1990's Internet boom. That is certainly not the case in most of the world. -

What NZ's Top Executives Are Paid

Friday, June 8, 2012 The Business | 5 What NZ’s top executives are paid Average Pay for 2011 Change 2010 to 2011 $1,507,996 –0.4% Average pay for 2010 was $1,514,373, an increase of 11.8% over the previous year Company Company Name Position Pay 2009 Pay 2010 Pay 2011 Change Profit Fonterra Andrew Ferrier CEO $3,630,000 $5,110,000 $5,000,000 -2% $771m Westpac George Frazis CEO NZ $3,410,588 $5,696,504 $4,597,683 -19% $451m Appointed Mar 09 Telecom Paul Reynolds CEO $5,406,450 $5,150,611 $3,023,074 -41% $166m SkyCity Entertainment Nigel Morrison CEO $2,563,908 $2,556,408 $2,970,577 16% $123m ANZ Banking Group David Hisco CEO NZ n/a n/a $2,882,705 n/a $899m Appointed Oct 10 Fletcher Building Jonathan Ling CEO $1,967,082 $2,713,494 $2,821,317 4% $291m Nuplex Industries Emery Severin CEO n/a n/a $2,495,787 n/a $69.3m Started April 10 The Warehouse Ian Morrice CEO $3,800,000 $2,844,000 $1,995,000 -30% $78.1m Resigned May 11 as an executive director Ebos Mark Waller CEO $1,330,000 $1,769,420 $1,901,218 7% $31.6m Air New Zealand Rob Fyfe CEO $1,487,100 $2,538,432 $1,859,934 -27% $81m Superannuation data unavailable for 09 Mighty River Power Doug Heffernan CEO $1,255,394 $1,317,469 $1,769,342 34% $127.1m Michael Hill Int. Mike Parsell CEO $702,597 $1,853,247 $1,729,870 -7% $34.5m NZ Exchange Mark Weldon CEO $1,392,300 $1,319,236 $1,628,871 23% $14.5m Auckland Airport Simon Moutter CEO $1,130,058 $1,297,665 $1,476,257 14% $100.8m Appointed Aug 08 Sky Network Television John Fellet CEO $1,287,500 $1,350,000 $1,467,500 9% $120.3m Solid Energy Don Elder -

Stoxx® Developed Markets Total Market Small Index

SIZE INDICES 1 STOXX® DEVELOPED MARKETS TOTAL MARKET SMALL INDEX Stated objective Key facts The EURO STOXX® Small Index provides a broad yet liquid » Liquid gateway to Eurozone small-cap stocks representation of small capitalization companies of 12 Eurozone countries: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, » Transparent and rules-based methodology Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. The index has a variable number of components and is part of the EURO » Buffer rule applied on parent index level aims at reducing turnover STOXX Size index family. » Weighted by free-float market capitalization » Serves as an underlying for a variety of financial products such as options, futures, and ETFs Descriptive statistics Index Market cap (USD bn.) Components (USD bn.) Component weight (%) Turnover (%) Full Free-float Mean Median Largest Smallest Largest Smallest Last 12 months STOXX Developed Markets Total Market Small Index 2,555.7 2,013.0 1.0 0.8 9.1 0.0 0.5 0.0 17.0 STOXX Developed Markets Total Market Index 44,524.3 38,816.9 8.9 2.3 618.0 0.0 1.6 0.0 3.0 Supersector weighting (top 10) Country weighting Risk and return figures1 Index returns Return (%) Annualized return (%) Last month YTD 1Y 3Y 5Y Last month YTD 1Y 3Y 5Y STOXX Developed Markets Total Market Small Index 1.8 6.7 20.7 45.1 78.3 24.2 10.0 20.3 12.9 11.9 STOXX Developed Markets Total Market Index 2.3 7.1 21.6 56.1 0.0 30.7 10.6 21.1 15.6 0.0 Index volatility and risk Annualized volatility (%) Annualized Sharpe ratio2 STOXX Developed Markets Total Market Small Index 7.6 8.5 8.5 13.1 14.2 1.2 1.1 2.1 0.9 0.8 STOXX Developed Markets Total Market Index 8.4 8.3 8.4 13.2 0.0 1.0 1.2 2.2 1.1 0.7 Index to benchmark Correlation Tracking error (%) STOXX Developed Markets Total Market Small Index 0.9 0.8 0.8 0.9 0.9 4.0 4.9 4.7 5.7 6.1 Index to benchmark Beta Annualized information ratio STOXX Developed Markets Total Market Small Index 0.8 0.8 0.9 0.9 0.9 0.1 -0.2 -0.2 -0.5 -0.4 1 For information on data calculation, please refer to STOXX calculation reference guide. -

S&P/ASX Index Consultation

S&P/ASX Index Consultation: New Zealand and PNG Secondary Listings on ASX and Index Eligibility October 2010 JOINT S&P / ASX Disclaimer: The information contained in this consultation paper (the “Paper”) is for the purposes of conducting a market survey only. It does not constitute investment and/or financial product advice. You should consider obtaining independent advice before making any investment and/or financial decisions. Neither ASX, ASX’s directors, officers, agents, employees, or contractors (“ASX Personnel”), nor Standard & Poor’s, Standard & Poor’s directors, officers, agents, employees or contractors (“S&P Personnel”) give any representation or warranty as to the reliability, accuracy or currency of the information contained in the Paper. To the extent permitted by law, neither ASX, ASX Personnel, Standard & Poor’s, S&P Personnel, shall be liable for, or responsible for, any losses, damages, costs, expenses or claims arising in any way (including by way of negligence) from anyone taking an action (or failing to act) based on, or in reliance on, the Paper or any information or material arising from or incidental to the Paper, whether in writing or otherwise. Any reference to “ASX” means “ASX Limited”, “ASX Operations Pty Limited” and all other related bodies corporate. Any reference to “S&P” or “Standard & Poor’s” means “Standard & Poor’s, a division of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.” and all of its affiliates. All currency values are in Australian dollars unless otherwise stated. © copyright 2010 Standard & Poor’s, a division of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, ASX Operations Pty Limited ABN 42 004 523 782 (ASXO). -

Partners with the Right Chemistry

Partners With The Right Chemistry 2016 Financial Year Half Year Report WorldReginfo - 4a7e06a9-e381-4ff9-9367-ce2c557199a1 Contents IFC Financial Highlights 1 Business Strategy 2 Chairman’s and Chief Executive Officer’s Report 4 Overview of the Allnex/Advent Proposal 6 Business Overview 8 Financial Report IBC Corporate Directory Revenue (in NZ$m) Operating EBITDA1 (in NZ$m) 1H16 700.5 1H16 65.7 685.8 126.0 54.5 5.9 1H15 1H15 811.8 60.4 1H14 815.2 1H14 59.5 1H13 828.7 1H13 57.6 1H12 746.4 1H12 57.3 Operating profit after-tax Net profit after-tax attributable (in NZ$m) to shareholders of the parent company (in NZ$m) 1H16 29.3 1H16 24.9 25.2 3.8 1H15 29.0 1H15 37.3 1H14 26.0 1H14 11.4 1H13 24.5 1H13 11.5 1H12 2 7.1 1H12 24.1 Total Continuing operations Non-continuing operations3,4 Regional sales (%) Regional EBITDA (%) 13% 22% ANZ ANZ 34% 41% 21% EMEA2 13% EMEA2 Americas Americas 24% 32% Asia Asia 1 Earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, amortisation, significant items, associates and minority interests. 2 Europe, Middle East & Africa. 3 Non-continuing operations include the businesses that have been sold or discontinued, including Nuplex Specialties, Nuplex Masterbatch and the Brazil resins operations, and as such differ slightly to the results historically reported as part of Nuplex’s segment disclosures for FY11 to FY14. 4 In FY15, non-continuing operations only includes 5 months of Nuplex Specialties and Nuplex Masterbatch and the results of Nuplex Brazil for the period. -

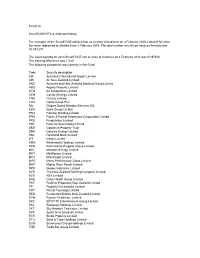

Code Security Description AIA Auckland International

5-Feb-16 SmartFONZ NTA & Allotment Notice The manager of the SmartFONZ advises that as at close of business on 4 February 2016 a total of Nil units has been redeemed or allotted since 3 February 2016. The total number of units on issue on that day was 99,074,271. The asset backing for each SmartFONZ unit at close of business on 4 February 2016 was $1.97440 The tracking difference was 1.43% The following companies are currently in the Fund: Code Security description AIA Auckland International Airport Limited AIR Air New Zealand Limited ANZ Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ARG Argosy Property Limited ATM A2 Corporation Limited CEN Contact Energy Limited CNU Chorus Limited COA Coats Group PLC DIL Diligent Board Member Services INC EBO Ebos Group Limited FBU Fletcher Building Limited FPH Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Corporation Limited FRE Freightways Limited FSF Fonterra Shareholders' Fund GMT Goodman Property Trust GNE Genesis Energy Limited HBL Heartland Bank Limited IFT Infratil Limited KMD Kathmandu Holdings Limited KPG Kiwi Income Property Group Limited MEL Meridian Energy Limited MET Metlifecare Limited MFT Mainfreight Limited MPG Metro Performance Glass Limited MRP Mighty River Power Limited NPX Nuplex Industries Limited NZR The New Zealand Refining Company Limited NZX NZX Limited OHE Orion Health Group Limited PCT Precinct Properties New Zealand Limited PFI Property For Industry Limited POT Port of Tauranga Limited RBD Restaurant Brands New Zealand Limited RYM Ryman Healthcare Limited SKC SKYCITY Entertainment Group Limited SKL Skellerup Holdings Limited SKT Sky Network Television Limited SPK Spark New Zealand Limited STR Stride Property Limited STU Steel & Tube Holdings Limited SUM Summerset Group Holdings Limited TME Trade Me Group Limited TPW TrustPower Limited TWR Tower Limited VCT Vector Limited VHP Vital Healthcare Property Trust WBC Westpac Banking Corporation WHS The Warehouse Group Limited XRO Xero limited ZEL Z Energy Limited For further information please contact: Smartshares Limited 0800 80 87 80 [email protected]. -

Summary and Recommended Investment Strategy. Investment Outlook

Information and Advice on the NZ Sharemarket from Securities Research Company's . Market Analysis Issue No. 351 P.O. Box 34-162, Auckland September 11, 2001. Inside Market Analysis BUY Commander Communications .................... 10-12 Company Review: We sold for a 603% gain, but ERG shares have since plunged in value ........... 14-16 Richina Pacific upgraded to “Buy” ............................. 5 Update: Scientific Services...................................... 16 Steel & Tube raises dividend 33%............................. 6 Toll Holdings, Lang Corporation bid for Rail .............. 9 Neglect Ratings of NZ and Australian Shares ......... 17 Editor and Research Director: James R Cornell (B.Com.) Summary and Recommended Investment Strategy. World stockmarkets fell sharply last week - dragging Australia and NZ lower. A further interest rate cut by the US Federal Reserve has highlighted continued weakness in the US economy, but will eventually lead to a moderate economic recovery. We are re-investing a little more of our cash reserve. Investment Outlook. On August 21, the US Federal Reserve made their growth companies to our portfolio. We are therefore seventh consecutive cut in interest rates. Rates were using another 2-5% of our cash reserve to buy shares in cut ¼% to 3½% - down from 6½ at the start of this Commander Communications. calendar year. The US stockmarket - and other major stockmarkets - have responded by plunging sharply to new lows! Investors could be mistaken for thinking falling interest rates are unfavourable for share prices! In fact, stockmarkets (i.e. investors) often act irrationally - especially in the short to medium term. Investors have seen six previous interest rate cuts this year while US New Zealand share prices have fallen. -

NSCC Important Notice

OTC# 210 Date: October 29, 2008 To: ALL PARTICIPANTS - OTC COMPARISON SYSTEM CASHIER, MANAGER REORGANIZATION Attention: OPERATIONS PARTNER/OFFICER, MANAGER P&S DEPT. CASHIER, MANAGER REORGANIZATION, GLOSSARY DEPT UPDATES TO THE LIST OF OTC CLEARED SECURITIES From: Underwriting Subject: OTC UPDATE CUSIP # SYMBOL NAME DATE ADD D95473225 GRYIF GERRY WEBER INT’L AG 10/29/2008 ADD G37704106 GLFMF GALIFORM PLC ORDINARY SHARES 10/29/2008 (UNITED KINGDOM) ADD 00089H106 ACSAY ACS ACTIVIDADES DE CONSTRUCCION 10/29/2008 Y SERVICIOS SA UNSPONSORED A ADD 00203U108 APNDY APN NEWS & MEDIA LTD 10/29/2008 UNSPONSORED ADR (NEW ZEALAND) ADD 00241Q101 AVOP AV1 GROUP, INC. COMMON STOCK 10/29/2008 ADD 00431B104 ACWRF ACCELEWARE CORP COMMON SHARES 10/29/2008 (CANADA) ADD 009136102 ANZFY AIR NEW ZEALAND LTD UNSPONS ADR 10/29/2008 (NEW ZEALAND) ADD 05070F100 ACKDY AUCKLAND INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT 10/29/2008 LIMITED UNSPONSORED ADR ADD 14950H103 CVLRY CAVALIER CORPORATION 10/29/2008 UNSPONSORED ADR (NEW ZEALAND) ADD 204476105 CATJY COMPANIA MINERA ATACOCHA S.A. 10/29/2008 UNSPONSORED ADR (PERU) ADD 21073R108 COENY CONTACT ENERGY LIMITED 10/29/2008 UNSPONSORED ADR (NEW ZEALAND) ADD 33774M205 FSPKY FISHER & PAYKEL HEALTHCARE CORP 10/29/2008 LTD UNSPONSORED ADR ADD 351645106 FXBY FOXBY CORP (FR:AMEX) 10/29/2008 ADD 367348109 GHSE GATEHOUSE MEDIA INC COM STK 10/29/2008 (FR:NYSE) Non-Confidential DTCC is now offering enhanced access to all important notices via a new, Web-based subscription service. The new notification system leverages RSS Newsfeeds, providing significant benefits including real-time updates and customizable delivery. To learn more and to set up your own DTCC RSS alerts, visit http://www.dtcc.com/subscription_form.php. -

Banner Year for Deloitte Top

DYNAMIC BUSINESS Exclusive report: Deloitte TOP 200 AWARDS Inside: Winners and finalists for 2016 Company Chief Executive Chairperson of the Year of the Year of theth YearYea Z Energy D7 Mike Bennetts, Christopher Moller D10 Z Energy D8 Ranjna Patel Visionary Banner year for leader Deloitte Top200 ZEnergy takes outtop honour at prestigiousbusiness awards 016 is abanner year for the their promise to the community,” the Accident Compensation Corporation Deloitte Top 200 —New Zea- judges added. (ACC) was well represented. land’s most prestigious busi- No surprise, then, that ZEnergy ACC’s turnaround in financial per- ness awards. CEO Mike Bennetts also takes the formance and public perception over 2Several Kiwi success stories have crown of Chief Executive of the Year recent years earned it the Excellence been honoured, along with arecord for 2016. in Governance award; while deputy number of women in the awards. Bennetts’ “inclusive” leadership chair, Trevor Janes, was afinalist in The successes goes beyond the has seen ZEnergy develop are- Chairperson of the Year. winners. spected and well known brand in a Christopher Moller, lauded for re- The total profits for the Top 200 short period of time while, again, cent successesaschair of SkyCity companies measured on the Deloitte delivering commendable financial re- Entertainment, Meridian Energy, and Index are also up nearly 19 per cent. sults for shareholders. NZTA, won that category for his The top honour was presented to Spark was also afinalist for Com- “courageous leadership”. ZEnergy which progressed from a pany of the Year, while their manag- Zespri Group had impressive finalist in the 2015 awards to the ing director Simon Moutter was revenue growth of 27.5 per cent —the standout winner in 2016 among the runner-up to Bennetts in the chief highest in the top 50 ranked com- Top 200 companies. -

Appreciating Value New Zealand Edition Six

Appreciating Value New Zealand Edition six March 2015 Contents Introduction Introduction 1 Does the increase in value of NZX listed companies have an impact on private company values? 2 Building quality financial models 6 In this edition of Appreciating Value Our second feature article shares our we reflect on a strong 2014 in terms of 15 Best Practice Financial Modelling deal activity, IPOs and listed share price tips. Given the importance of financial Risk Free Rate revisited 10 performance. Against this backdrop, models in business decision making, it and certainly a surprise compared to is critical that those models are robust Deals update 12 expectations this time last year, we and understandable. Our specialist observe a significant decline in the business modelling team has developed risk-free rate due to a steady decline in these tips through their experience Government bond yields over the last creating and reviewing financial models Cost of Capital and Market Multiples 16 Justin Liddell quarter of 2014 and continuing into throughout New Zealand. Our team’s Partner 2015. credentials are underpinned with team (09) 355 8330 members Alex Gordon and Michael In our first feature article we discuss [email protected] Clarke having achieved first, second the higher trading multiples observed and third placings between them at the from New Zealand listed companies last three ModelOff Financial Modelling and consider what impact this is likely World Championships in New York. to have on private company and SME values. Finally we include our regular Deals update and cost of capital and multiples of listed companies. -

Impact of Anonymity on Liquidity in Limit Order Books: Evidence from Cross-Listed Stocks

Impact of Anonymity on Liquidity in Limit Order Books: Evidence from Cross-listed Stocks Jane Chau* Corresponding author: PhD candidate in the School of Accounting and Finance University of Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia Email: [email protected] Alex Frino CEO of Capital Markets CRC Limited & Professor of finance in the Discipline of Finance The University of Sydney Business School Email: [email protected]. Gary Tian Professor of finance in the School of Accounting and Finance University of Wollongong Email: [email protected] Shiguang Ma Senior Lecturer in the School of Accounting and Finance University of Wollongong Email: [email protected]. This Draft: 25 November, 2012 * Jane Chau is supported by the Capital Markets Cooperative Research Centre Scholarship. The authors thank the Securities Industry Research Centre of Asia-Pacific (SIRCA) for the provision of data. 1 Abstract This paper examines anonymity effects on liquidity migration of cross-listed stocks using a natural experiment created by the staggered move to anonymity regime undertaken by ASX and NZX. The 2SLS instrumental variable estimation shows two interesting trends. When considering liquidity impact on cross-listed stocks after ASX switched to anonymous trading, bid-ask spreads, quoted depth and trading volume improve on ASX, but deteriorate on NZX. On the other hand, when considering NZX’s adoption of anonymous trading, liquidity decreases on ASX, but increases on NZX. Consistent with our hypothesis, anonymity attracts the trading of cross-listed stocks from the foreign counterparty. Results also suggest the existence of commonality in liquidity in financial markets, and the inclusion of this commonality in natural experiment studies may be necessary. -

Summary and Recommended Investment Strategy. Investment

Information and Advice on the Australian and NZ Sharemarket from Securities Research Company's . Market Analysis Issue No. 395 www.stockmarket.co.nz May 10, 2005 Inside Market Analysis Markets dip sharply, but offer good value .................. 1 Warrant / Option Analysis .................................. 10, 11 Colonial Motors. Warrant / Option Analysis identifies new realises cash from surplus property .......................... 3 speculative opportunity, plus current advice Sonnet Corporation plans major acquisition .............. 7 on previous options ........................................... 11 -14 Editor and Research Director: James R Cornell (B.Com.) Summary and Recommended Investment Strategy. World stockmarkets have dipped sharply over the last month, but too many shares already look under-valued. We recommend that investors remain close to fully invested in the Recommended Portfolio. Investment Outlook. The global stockmarket correction that began in Februay Stockmarket Forecasts has acelerated with prices falling rapidly over the last One-Month One-Year month. This is no doubt flaahing big “Sell” signals for all Australia: 55% (Neutral) 67% (Bullish) New Zealand: 52% (Neutral) 38% (Bearish) the technical analysts and other trend followers. Sometimes, however, a stockmarket dip is simply a random fluctuation. A sharp decline does make us a bit nervous. So this is probably a time to be cautious. Investors should seek to invest with the trend - so if prices are going down then the best option is usually to sit on any surplus cash and buy additional shares once prices have stablised and New Zealand NZX 50 Index started to go back up. The main reason we think this is a short (albeit very sharp) decline and not a major long term downtrend is simply that too many good quality shares already appear to offer excellent value.