Business Models: a Unit of Analysis for Company Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Initial Briefing for the Purposes of the Inquiry

INITIAL BRIEFING FOR THE PURPOSES OF THE INQUIRY - History of the Earthquake Commission 26 October 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 1929 – 2009 1 Government response to the 1929 and 1931 earthquakes 1 Earthquake and War Damage Act 1944 2 Review and reform of the 1944 Act 3 Earthquake Commission Act 1993 (EQC Act) 3 Preparedness following the EQC Act 4 EQC claims mostly cash settled 5 Crown Entities Act 2004 6 2010 6 Position prior to the first Canterbury earthquake 6 4 September 2010 earthquake 7 Residential building claims 7 Residential land 8 Progress with Canterbury claims 8 Managing liabilities 9 EQC’s role 10 2011 10 Cyclone Wilma 10 22 February 2011 earthquake 10 EQC’s additional roles 11 Rapid Assessment 11 Emergency repairs 12 13 June 2011 earthquake 12 Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority - Zoning and Crown offers 13 Additional land remediation 13 High Court Declaratory Judgment – Reinstatement of cover 13 Progress with Canterbury claims 13 New Technical Categories (TC1, TC2 and TC3) 14 Relationship with private insurers 14 Staff and contractors 15 23 December 2011 earthquake 15 Residential land claims 15 Statement of Intent 2011-14 16 Reviews of EQC 16 2012 17 Progress with Canterbury claims 17 Canterbury Earthquake (Earthquake Commission Act) Order 2012 18 Royal Commission of Inquiry into Building Failure Caused by Canterbury Earthquakes 19 Unclaimed damage – Ministerial Direction 19 Nelson floods 19 Residential land damage 19 Managing liabilities 20 Reviews of EQC 20 Review of EQC’s 2012 Christchurch Recruitment Processes -

Download PDF

Table of Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................... 2 What Auckland consumers have to say about electricity retail issues ........................... 3 The EAP has not fully met the requirements of the terms of reference ......................... 4 The big-5 incumbent retailers are to blame for residential price increases .................... 5 Sweet-heart deals with Tiwai Smelter are keeping prices artificially high ...................... 6 Stronger wholesale and retail competition needed to make electricity more affordable ... 8 Saves & Winbacks is making the two-tier retail market problem worse ...................... 11 Late payment penalties disadvantage vulnerable Kiwis unable to pay on time ............. 14 Prepayment arrangements exploit vulnerable consumers ......................................... 18 There are questions about compliance with the Vulnerable Consumer Guidelines and the objectives of the Guidelines .................................................................................. 19 Concluding remarks and recommendations ............................................................. 20 Appendix 1: Price increases over the last 18-years largely driven by retail (energy) .... 22 Appendix 2: Manipulation of pricing data can make it look like lines are to blame ........ 27 Appendix 3: The electricity retail and generation markets are highly “concentrated” .... 30 Appendix 4: Retail competition improvements driven by the last inquiry reforms -

FY21 Results Overview

Annual Report 2021 01 Chorus Board and management overview 14 Management commentary 24 Financial statements 60 Governance and disclosures 92 Glossary FY21 results overview Fixed line connections1 Broadband connections1 FY21 FY20 FY21 FY20 1,340,000 1,415,000 1,180,000 1,206,000 Fibre connections1 Net profit after tax FY21 FY20 FY21 FY20 871,000 751,000 $47m $52m EBITDA2 Customer satisfaction Installation Intact FY21 FY20 FY21 FY21 $649m $648m 8.2 out of 10 7.5 out of 10 (target 8.0) (target 7.5) Dividend Employee engagement score3 FY21 FY20 FY21 FY20 25cps 24cps 8.5 out of 103 8.5 This report is dated 23 August 2021 and is signed on behalf of the Board of Chorus Limited. Patrick Strange Mark Cross Chair Chair Audit & Risk Management Committee 1 Excludes partly subsidised education connections provided as part of Chorus’ COVID-19 response. 2 Earnings before interest, income tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) is a non-GAAP profit measure. We monitor this as a key performance indicator and we believe it assists investors in assessing the performance of the core operations of our business. 3 Based on the average response to four key engagement questions. Dear investors Our focus in FY21 was to help consumers especially important because fixed wireless services don’t capitalise on the gigabit head start our fibre provide the same level of service as fibre - or even VDSL in network has given New Zealand. We knocked most cases – and these service limitations often aren’t made clear to the customer. on about a quarter of a million doors and supported our 100 or so retailers to connect As expected, other fibre companies continued to win copper customers in those areas where they have overbuilt our another 120,000 consumers to fibre. -

Westpac Online Investment Loan Acceptable Securities List - Effective 3 September2021

Westpac Online Investment Loan Acceptable Securities List - Effective 3 September2021 ASX listed securities ASX Code Security Name LVR ASX Code Security Name LVR A2M The a2 Milk Company Limited 50% CIN Carlton Investments Limited 60% ABC Adelaide Brighton Limited 60% CIP Centuria Industrial REIT 50% ABP Abacus Property Group 60% CKF Collins Foods Limited 50% ADI APN Industria REIT 40% CL1 Class Limited 45% AEF Australian Ethical Investment Limited 40% CLW Charter Hall Long Wale Reit 60% AFG Australian Finance Group Limited 40% CMW Cromwell Group 60% AFI Australian Foundation Investment Co. Ltd 75% CNI Centuria Capital Group 50% AGG AngloGold Ashanti Limited 50% CNU Chorus Limited 60% AGL AGL Energy Limited 75% COF Centuria Office REIT 50% AIA Auckland International Airport Limited 60% COH Cochlear Limited 65% ALD Ampol Limited 70% COL Coles Group Limited 75% ALI Argo Global Listed Infrastructure Limited 60% CPU Computershare Limited 70% ALL Aristocrat Leisure Limited 60% CQE Charter Hall Education Trust 50% ALQ Als Limited 65% CQR Charter Hall Retail Reit 60% ALU Altium Limited 50% CSL CSL Limited 75% ALX Atlas Arteria 60% CSR CSR Limited 60% AMC Amcor Limited 75% CTD Corporate Travel Management Limited ** 40% AMH Amcil Limited 50% CUV Clinuvel Pharmaceuticals Limited 40% AMI Aurelia Metals Limited 35% CWN Crown Limited 60% AMP AMP Limited 60% CWNHB Crown Resorts Ltd Subordinated Notes II 60% AMPPA AMP Limited Cap Note Deferred Settlement 60% CWP Cedar Woods Properties Limited 45% AMPPB AMP Limited Capital Notes 2 60% CWY Cleanaway Waste -

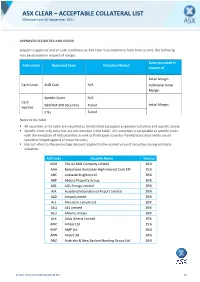

Asx Clear – Acceptable Collateral List 28

et6 ASX CLEAR – ACCEPTABLE COLLATERAL LIST Effective from 20 September 2021 APPROVED SECURITIES AND COVER Subject to approval and on such conditions as ASX Clear may determine from time to time, the following may be provided in respect of margin: Cover provided in Instrument Approved Cover Valuation Haircut respect of Initial Margin Cash Cover AUD Cash N/A Additional Initial Margin Specific Cover N/A Cash S&P/ASX 200 Securities Tiered Initial Margin Equities ETFs Tiered Notes to the table . All securities in the table are classified as Unrestricted (accepted as general Collateral and specific cover); . Specific cover only securities are not included in the table. Any securities is acceptable as specific cover, with the exception of ASX securities as well as Participant issued or Parent/associated entity issued securities lodged against a House Account; . Haircut refers to the percentage discount applied to the market value of securities during collateral valuation. ASX Code Security Name Haircut A2M The A2 Milk Company Limited 30% AAA Betashares Australian High Interest Cash ETF 15% ABC Adelaide Brighton Ltd 30% ABP Abacus Property Group 30% AGL AGL Energy Limited 20% AIA Auckland International Airport Limited 30% ALD Ampol Limited 30% ALL Aristocrat Leisure Ltd 30% ALQ ALS Limited 30% ALU Altium Limited 30% ALX Atlas Arteria Limited 30% AMC Amcor Ltd 15% AMP AMP Ltd 20% ANN Ansell Ltd 30% ANZ Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd 20% © 2021 ASX Limited ABN 98 008 624 691 1/7 ASX Code Security Name Haircut APA APA Group 15% APE AP -

New Zealand Broadband: Free TV's and Fridges - the Consumer Wins but Is It Sustainable?

MARKET PERSPECTIVE New Zealand Broadband: Free TV's and Fridges - The Consumer Wins but is it Sustainable? Peter Wise Shane Minogue Monica Collier Jefferson King Sponsored by Spark New Zealand Limited IDC OPINION The New Zealand telecommunications market is shifting; from a focus around better and faster connectivity, to service innovations and value. Consumers are enjoying better internet connectivity and a raft of competitive offers from more than 90 retailers. Retailers, however, are feeling the pinch of decreasing margins. Questions are starting to arise about the sustainability of such a competitive retail marketplace. Total telecommunications market revenues increased by 1.1% from NZ$5.361 billion in the year to December 2016 to NZ$5.421 billion in the year to December 2017. IDC forecasts that this growth will continue in future years with a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 1.4% to 2021. However, this growth disguises the true story of a market that is displaying extreme price pressure and competition in both fixed and mobile. Overall, ARPUs are either flat or declining in both broadband and mobile and in the broadband space Retail Service Providers (RSPs) continue to compete away any chance of strong, sustainable ARPU growth. New Zealand telecommunication's structural separation and national broadband plan have created new constructs and market dynamics. The UFB initiative has commoditised fibre in New Zealand. Consumer fibre plan prices have plummeted from averaging over NZ$200 per month in 2013 to around NZ$85 per month as at February 2018. Fibre is available to more than a million homes and premises, and over a third have made the switch. -

Rakon Letterhead NZ Dec 2014

27 May 2021 5G momentum drives Rakon’s growth Revenue $128.3 million, 8% higher than FY2020 Underlying EBITDA1 $23.5 million, 59% higher than FY2020 Net profit after tax $9.6 million, 142% higher than FY2020 Rapid response and ongoing adaption through worldwide Covid-19 disruptions Sustained growth in Telecommunications revenue, driven by increased 5G momentum Market opportunities captured through agility and strong supply chain relationships FY2022 guidance confirmed of Underlying EBITDA range of $27-32 million All amounts are in New Zealand Dollars Rakon (NZX.RAK) today announced strong improvements in revenue and earnings for the year to 31 March 2021, as sustained demand from the global telecommunications sector for its industry-leading frequency control and timing solutions helped to offset the significant disruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic. Revenue for the year to 31 March 2021 rose 8% to $128.3 million from $119.0 million a year earlier. Gross margin improvements and careful cost management drove a 59% increase in underlying EBITDA to $23.5 million (2020: $14.8m), ahead of the company’s guidance of $20-22 million. Net profit after tax rose 142% to $9.6 million from $4.0 million in the same period a year ago. Rakon Chair Bruce Irvine said the company’s FY2021 performance was a testament to the capability, resilience and commitment of Rakon’s global team, and the agility and responsiveness of the business. “It has been a particularly challenging year. Rakon’s strong performance through these challenges reflects the sustained demand for its industry-leading products and builds on the solid operating improvements made in recent years.” Managing Director Brent Robinson said: “This result has been achieved despite the considerable disruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic, and it demonstrates our position as the supplier of choice in high-reliability connectivity solutions. -

Bringing the Future Faster

6mm hinge Bringing the future faster. Annual Report 2019 WorldReginfo - 7329578e-d26a-4187-bd38-e4ce747199c1 Bringing the future faster Spark New Zealand Annual Report 2019 Bringing the future faster Contents Build customer intimacy We need to understand BRINGING THE FUTURE FASTER and anticipate the needs of New Zealanders, and Spark performance snapshot 4 technology enables us Chair and CEO review 6 to apply these insights Our purpose and strategy 10 to every interaction, Our performance 12 helping us serve our Our customers 14 customers better. Our products and technology 18 Read more pages 7 and 14. Our people 20 Our environmental impact 22 Our community involvement 24 Our Board 26 Our Leadership Squad 30 Our governance and risk management 32 Our suppliers 33 Leadership and Board remuneration 34 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Financial statements 38 Notes to the financial statements 44 Independent auditor’s report 90 OTHER INFORMATION Corporate governance disclosures 95 Managing risk framework roles and 106 responsibilities Materiality assessment 107 Stakeholder engagement 108 Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) content 109 index Glossary 112 Contact details 113 This report is dated 21 August 2019 and is signed on behalf of the Board of Spark New Zealand Limited by Justine Smyth, Chair and Charles Sitch, Chair, Audit and Risk Management Committee. Justine Smyth Key Dates Annual Meeting 7 November 2019 Chair FY20 half-year results announcement 19 February 2020 FY20 year-end results announcement 26 August 2020 Charles Sitch Chair Audit and Risk Management Committee WorldReginfo - 7329578e-d26a-4187-bd38-e4ce747199c1 Create New Zealand’s premier sports streaming business Spark Sport is revolutionising how New Zealanders watch their favourite sports events. -

Summary and Recommended Investment Strategy. Investment Outlook

Thirty Four Years of Independent Information and Unbiased Advice on the Australian and NZ Stockmarkets Market Analysis Issue No. 516 www.stockmarket.co.nz June 8, 2015 Inside Market Analysis Nuplex Industries to lift dividend ................................ 2 Neglect Ratings of New Zealand Shares ................... 7 ALS Life Sciences becomes largest division.............. 2 Neglect Ratings of Australian Shares ................ 10, 11 Private Equity firms buys into Cardno ........................ 4 Short Interest in Australian Shares .................... 11, 12 Founder: James R Cornell (B.Com.) Summary and Recommended Investment Strategy. Successful non-resource exporters will continue to benefit significantly from the downturn in the resource sector and the resulting lower Australian dollar exchange rate. Remain fully invested. Investment Outlook. Our Stockmarket Forecasts remain relatively Bearish to Stockmarket Forecasts Neutral and sentiment remains depressed, but it is difficult One-Month One-Year to make a case for a significant stockmarket decline. Australia: 25% (Bearish) 58% (Neutral) Media reports on the Australian Resource sector are New Zealand: 64% (Bullish) 41% (Neutral) depressing, but are an example of Peter Lynch's “penultimate preparedness”. Commodity prices have fallen and new mining developments have been cut back 80-90% . so the media (and investors) are now expecting and “prepared” for commodity prices to fall and mining developments to be cut back! Stockmarkets peak (and subsequently decline significantly) from an environment of excessive optimism New Zealand and over-valuation. The sort of thing that we saw in the NZX 50 Index 1980's Investment and Property boom or the late 1990's Internet boom. That is certainly not the case in most of the world. -

What NZ's Top Executives Are Paid

Friday, June 8, 2012 The Business | 5 What NZ’s top executives are paid Average Pay for 2011 Change 2010 to 2011 $1,507,996 –0.4% Average pay for 2010 was $1,514,373, an increase of 11.8% over the previous year Company Company Name Position Pay 2009 Pay 2010 Pay 2011 Change Profit Fonterra Andrew Ferrier CEO $3,630,000 $5,110,000 $5,000,000 -2% $771m Westpac George Frazis CEO NZ $3,410,588 $5,696,504 $4,597,683 -19% $451m Appointed Mar 09 Telecom Paul Reynolds CEO $5,406,450 $5,150,611 $3,023,074 -41% $166m SkyCity Entertainment Nigel Morrison CEO $2,563,908 $2,556,408 $2,970,577 16% $123m ANZ Banking Group David Hisco CEO NZ n/a n/a $2,882,705 n/a $899m Appointed Oct 10 Fletcher Building Jonathan Ling CEO $1,967,082 $2,713,494 $2,821,317 4% $291m Nuplex Industries Emery Severin CEO n/a n/a $2,495,787 n/a $69.3m Started April 10 The Warehouse Ian Morrice CEO $3,800,000 $2,844,000 $1,995,000 -30% $78.1m Resigned May 11 as an executive director Ebos Mark Waller CEO $1,330,000 $1,769,420 $1,901,218 7% $31.6m Air New Zealand Rob Fyfe CEO $1,487,100 $2,538,432 $1,859,934 -27% $81m Superannuation data unavailable for 09 Mighty River Power Doug Heffernan CEO $1,255,394 $1,317,469 $1,769,342 34% $127.1m Michael Hill Int. Mike Parsell CEO $702,597 $1,853,247 $1,729,870 -7% $34.5m NZ Exchange Mark Weldon CEO $1,392,300 $1,319,236 $1,628,871 23% $14.5m Auckland Airport Simon Moutter CEO $1,130,058 $1,297,665 $1,476,257 14% $100.8m Appointed Aug 08 Sky Network Television John Fellet CEO $1,287,500 $1,350,000 $1,467,500 9% $120.3m Solid Energy Don Elder -

The Climate Risk of New Zealand Equities

The Climate Risk of New Zealand Equities Hamish Kennett Ivan Diaz-Rainey Pallab Biswas Introduction/Overview ØExamine the Climate Risk exposure of New Zealand Equities, specifically NZX50 companies ØMeasuring company Transition Risk through collating firm emission data ØCompany Survey and Emission Descriptives ØPredicting Emission Disclosure ØHypothetical Carbon Liabilities 2 Measuring Transition Risk ØTransition Risk through collating firm emissions ØAimed to collate emissions for all the constituents of the NZX50. ØUnique as our dataset consists of Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 emissions, ESG scores and Emission Intensities for each firm. ØCarbon Disclosure Project (CDP) reports, Thomson Reuters Asset4, Annual reports, Sustainability reports and Certified Emissions Measurement and Reduction Scheme (CEMAR) reports. Ø86% of the market capitilisation of the NZX50. 9 ØScope 1: Classified as direct GHG emissions from sources that are owned or controlled by the company. ØScope 2: Classified as indirect emissions occurring from the generation of purchased electricity. ØScope 3: Classified as other indirect GHG emissions occurring from the activities of the company, but not from sources owned or controlled by the company. (-./01 23-./014) Ø Emission Intensity = 6789 :1;1<=1 4 Company Survey Responses Did not Email No Response to Email Responded to Email Response Company Company Company Air New Zealand Ltd. The a2 Milk Company Ltd. Arvida Group Ltd. Do not report ANZ Group Ltd. EBOS Ltd. Heartland Group Holdings Ltd. Do not report Argosy Property Ltd. Goodman Property Ltd. Metro Performance Glass Ltd. Do not report Chorus Ltd. Infratil Ltd. Pushpay Holdings Ltd. Do not report Contact Energy Ltd. Investore Property Ltd. -

FNZ Basket 14102010

14-Oct-10 smartFONZ Basket Composition Composition of a basket of securities and cash equivalent to 200,000 NZX 50 Portfolio Index Fund units effective from 14 October 2010 The new basket composition applies to applications and withdrawals. Cash Portion: $ 1,902.98 Code Security description Shares ABA Abano Healthcare Group Limited 88 AIA Auckland International Airport Limited Ordinary Shares 6,725 AIR Air New Zealand Limited (NS) Ordinary Shares 2,784 AMP AMP Limited Ordinary Shares 432 ANZ Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited Ord Shares 212 APN APN News & Media Limited Ordinary Shares 1,759 APT AMP NZ Office Trust Ordinary Units 8,453 ARG Argosy Property Trust Ordinary Units 4,344 CAV Cavalier Corporation Limited Ordinary Shares 482 CEN Contact Energy Limited Ordinary Shares 1,508 EBO Ebos Group Limited Ordinary Shares 537 FBU Fletcher Building Limited Ordinary Shares 1,671 FPA Fisher & Paykel Appliances Holdings Limited Ordinary Shares 6,128 FPH Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Corporation Limited Ord Shares 3,106 FRE Freightways Limited Ordinary Shares 1,625 GFF Goodman Fielder Limited Ordinary Shares 3,990 GMT Macquarie Goodman Property Trust Ordinary Units 8,004 GPG Guinness Peat Group Plc Ordinary Shares 15,588 HLG Hallenstein Glasson Holdings Limited Ordinary Shares 430 IFT Infratil Limited Ordinary Shares 6,363 KIP Kiwi Income Property Trust Ordinary Units 10,287 KMD Kathmandu Holdings Limited Ordinary Shares 690 MFT Mainfreight Limited Ordinary Shares 853 MHI Michael Hill International Limited Ordinary Shares 1,433 NPX