Open PDF 111KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operation Kipion: Royal Navy Assets in the Persian by Claire Mills Gulf

BRIEFING PAPER Number 8628, 6 January 2020 Operation Kipion: Royal Navy assets in the Persian By Claire Mills Gulf 1. Historical presence: the Armilla Patrol The UK has maintained a permanent naval presence in the Gulf region since October 1980, when the Armilla Patrol was established to ensure the safety of British entitled merchant ships operating in the region during the Iran-Iraq conflict. Initially the Royal Navy’s presence was focused solely in the Gulf of Oman. However, as the conflict wore on both nations began attacking each other’s oil facilities and oil tankers bound for their respective ports, in what became known as the “tanker war” (1984-1988). Kuwaiti vessels carrying Iraqi oil were particularly susceptible to Iranian attack and foreign-flagged merchant vessels were often caught in the crossfire.1 In response to a number of incidents involving British registered vessels, in October 1986 the Royal Navy began accompanying British-registered vessels through the Straits of Hormuz and in the Persian Gulf. Later the UK’s Armilla Patrol contributed to the Multinational Interception Force (MIF), a naval contingent patrolling the Persian Gulf to enforce the UN-mandated trade embargo against Iraq, imposed after its invasion of Kuwait in August1990.2 In the aftermath of the 2003 Iraq conflict, Royal Navy vessels, deployed as part of the Armilla Patrol, were heavily committed to providing maritime security in the region, the protection of Iraq’s oil infrastructure and to assisting in the training of Iraqi sailors and marines. 1.1 Assets The Type 42 destroyer HMS Coventry was the first vessel to be deployed as part of the Armilla Patrol, followed by RFA Olwen. -

The Naval Engineer

THE NAVAL ENGINEER SPRING/SUMMER 2019, VOL 06, EDITION NO.2 All correspondence and contributions should be forwarded to the Editor: Welcome to the new edition of TNE! Following the successful relaunch Clare Niker last year as part of our Year of Engineering campaign, the Board has been extremely pleased to hear your feedback, which has been almost entirely Email: positive. Please keep it coming, good or bad, TNE is your journal and we [email protected] want to hear from you, especially on how to make it even better. By Mail: ‘..it’s great to see it back, and I think you’ve put together a great spread of articles’ The Editor, The Naval Engineer, Future Support and Engineering Division, ‘Particularly love the ‘Recognition’ section’ Navy Command HQ, MP4.4, Leach Building, Whale Island, ‘I must offer my congratulations on reviving this important journal with an impressive Portsmouth, Hampshire PO2 8BY mix of content and its presentation’ Contributions: ‘..what a fantastic publication that is bang up to date and packed full of really Contributions for the next edition are exciting articles’ being sought, and should be submitted Distribution of our revamped TNE has gone far and wide. It is hosted on by: the MOD Intranet, as well as the RN and UKNEST webpages. Statistics taken 31 July 2019 from the external RN web page show that there were almost 500 visits to the TNE page and people spent over a minute longer on the page than Contributions should be submitted average. This is in addition to all the units and sites that received almost electronically via the form found on 2000 hard copies, those that have requested electronic soft copies, plus The Naval Engineer intranet homepage, around 700 visitors to the internal site. -

1/23/2019 Sheet1 Page 1 Date Ship Hull Number Port Notes 31-Dec

Sheet1 1/23/2019 Date Ship Hull Number Port Notes 31-Dec-18 USNS Cesar Chavez T-AKE 14 Sembawang 31-Dec-18 USCGC William R Flores WPC 1103 Miami 31-Dec-18 USCGC Skipjack WPB 87353 Intracoastal City 31-Dec-18 USCGC Sanibel WPB 1312 Woods Hole 31-Dec-18 USCGC Resolute WMEC 620 St Petersburg FL 31-Dec-18 USCGC Oliver Berry WPC 1124 Honolulu 31-Dec-18 USCGC Flyingfish WPB 87346 Little Creek 31-Dec-18 USCGC Donald Horsley WPC 1127 San Juan 31-Dec-18 USCGC Bailey Barco WPC 1122 Ketchikan 31-Dec-18 USAV Missionary Ridge LCU 2028 Norfolk 31-Dec-18 USAV Hormigueros LCU 2024 Kuwait 31-Dec-18 MV Cape Hudson T-AKR 5066 Pearl Harbor 31-Dec-18 INS Nirupak J 20 Kochi 31-Dec-18 INS Kuthar P 46 Visakhapatnam 31-Dec-18 HNLMS Urania Y 8050 Drimmelen 31-Dec-18 HNLMS Holland P 840 Amsterdam 31-Dec-18 HMS Argyll F 231 Yokosuka 31-Dec-18 ABPF Cape Leveque Nil Darwin 30-Dec-18 HMCS Ville de Quebec FFH 332 Dubrovnik SNMG2 30-Dec-18 USNS Yano T-AKR 297 Norfolk 30-Dec-18 USNS Trenton T-EPF 5 Taranto 30-Dec-18 USNS Fall River T-EPF 4 Sattahip 30-Dec-18 USNS Catawba T-ATF 168 Jebel Ali 30-Dec-18 USCGC Washington WPB 1331 Guam 30-Dec-18 USCGC Sitkinak WPB 1329 Fort Hancock 30-Dec-18 USCGC Flyingfish WPB 87346 Norfolk 30-Dec-18 USCGC Blue Shark WPB 87360 Everett 30-Dec-18 HNLMS Urk M 861 Zeebrugge 30-Dec-18 HMS Brocklesby M 33 Mina Sulman 30-Dec-18 ABPF Cape Nelson Nil Darwin 29-Dec-18 ESPS Infanta Elena P76 Cartagena Return from patrol 29-Dec-18 RFS Ivan Antonov 601 Baltiysk Maiden Arrival 29-Dec-18 USNS Bowditch T-AGS 62 Guam 29-Dec-18 USNS Amelia Earhart T-AKE 6 -

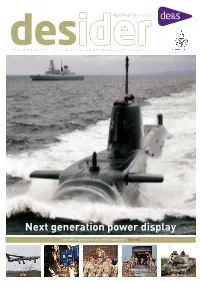

Next Generation Power Display

Apr/May 10 Issue 24 desthe magazine for defenceider equipment and support Next generation power display Latest DE&S organisation chart and PACE supplement See inside Parc Chain Dress for Welcome Keeping life gang success home on track Picture: BAE Systems NEWS 5 4 Keeping on track Armoured vehicles in Afghanistan will be kept on track after DE&S extended the contract to provide metal tracks the vehicles run on. 8 UK Apache proves its worth The UK Apache attack helicopter fleet has reached the landmark of 20,000 flying hours in support of Operation Herrick 8 Just what the doctor ordered! DE&S’ Chief Operating Officer has visited the 2010 y Nimrod MRA4 programme at Woodford and has A given the aircraft the thumbs up after a flight. /M 13 Triumph makes T-boat history The final refit and refuel on a Trafalgar class nuclear submarine has been completed in Devonport, a pril four-year programme of work costing £300 million. A 17 Transport will make UK forces agile New equipment trailers are ready for tank transporter units on the front line to enable tracked vehicles to cope better with difficult terrain. 20 Enhancement to a soldier’s ‘black bag’ Troops in Afghanistan will receive a boost to their personal kit this spring with the introduction of cover image innovative quick-drying towels and head torches. 22 New system is now operational Astute and Dauntless, two of the most advanced naval A new command system which is central to the ship’s fighting capability against all kinds of threats vessels in the world, are pictured together for the first time is now operational on a Royal Navy Type 23 frigate. -

Navy News Week 47-1

NAVY NEWS WEEK 47-1 26 November 2017 Yemen’s Houthis threaten to attack warships, oil tankers if ports stay closed Yemen’s armed Houthi movement said on Sunday it could attack warships and oil tankers from enemy countries in retaliation against the closure of Yemeni ports by a Saudi-led military coalition last week Saudi Arabia has blamed the Iran- allied Houthis for firing a ballistic missile towards Riyadh airport on Nov 4. Two days later, the Saudi-led coalition responded by closing access to Yemeni ports, saying this was needed to stop arms reaching the Houthis. The United Nations says the closure could cause a famine in Yemen that could kill millions of people if ports are not reopened. “The battleships and oil tankers of the aggression and their movements will not be safe from the fire of Yemeni naval forces if they are directed by the senior leadership (to attack),” the Houthis’ official media outlet Al Masirah said on its website, citing a military commander. Yemen lies beside the southern mouth of the Red Sea, one of the most important trade routes in the world for oil tankers, which pass near Yemen’s shores while heading from the Middle East through the Suez Canal to Europe. The Houthis, fighters drawn mainly from Yemen’s Zaidi Shi‘ite minority and allied to long-serving former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, control much of Yemen including the capital San‘aa. The Saudi-led military alliance is fighting in support of the internationally recognised government of President Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who is based in the southern port of Aden. -

Coronation Review of the Fleet

CORONATION REVIEW OF THE FLEET. While every care has been taken in the preparation of this show, accuracy cannot be guaranteed. CLICK TO CONTINUE, APPLIES TO ALL SLIDES Acknowledgement: Much of the information for this presentation was gathered from various internet websites and publications from the era. The naming of the ships came from a chart provided by Bill Brimson. The chart was published at the Admiralty 22nd May 1953, under the Superintendence of Vice-Admiral A. Day, C.B. C.B.E. D.S.O. Hydroggrapher Cover of the Official Programme The programme was published under the authority of Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth. PROGRAMME FOR THE DAY 8 a.m. Ships dress over-all. 5.10 p.m. HMS Surprise anchors at the head of line E. Morning Her Majesty The Queen receives the Board of ( approximately) Admiralty and certain Senior Officers on board 5.35 p.m. The flypast by Naval Aircraft takes place. HMS Surprise. Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen 1 p.m. Her Majesty the Queen holds a luncheon party Mother, and some other members of the Royal on board HMS Surprise. Family disembark to return to London. 2.35 p.m. Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, 6.30 p.m. Her Majesty The Queen holds a Sherry Party on Her Royal Highness Princess Margaret and board HMS Surprise. other members of the Royal Family arrive by 8.30 p.m. Her Majesty The Queens dines on board train and embark in HMS Surprise. HMS Vanguard. 3 p.m. Preceded by Trinity House vessel Patricia and 10.30 p.m. -

The CNOA Newsletter for May 2019

The CNOA Newsletter for May 2019 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cnoa.org.uk Contents Next CNOA meeting details Chairman’s Flag Hoist Future speakers & events An Oasis of Peace in Middle East New RN Facility for East of Suez Seafarers UK visit Harbour Masters CNOA Guest Night booking is open Members asked to provide talks P&O Cross Channel trip is open Naval Pilots of “Forgotten Few” Boats Chartered in the Pacific CNOA Member charity abseil Application for CNOA membership HMS PURSUER leading other P2000 class patrol boats on the Solent as part of their annual squadron exercise. The 1st Patrol Boat Squadron have five ships based in HMNB Portsmouth while the others are based around the UK, with two in Gibraltar, and affiliated to allocated universities. As well as providing training and maritime experience for the university students, the patrol vessels provide support to wider Fleet tasking and often take the role of attack craft in maritime exercise around the UK and Europe. Commanded by Lieutenants with a small Royal Navy ship’s company, university students also crew the ships to learn about the Service and to enjoy the camaraderie of working in a small team. Photo © Copyright MoD Navy 2019 © Crown Copyright MoD Navy 2019 Ladies and Gentlemen, The next meeting of the Association will be on Friday the 10th of May in the Warfare Room, RSME HQ Brompton Barracks 19.45 for 20.00 when CNOA Member, Rev. Keith McNicol will talk about a village of Peace in the midst of conflict. The evening will then continue with refreshments and fellowship in the Officers Mess. -

Plymouth Eligibility and Application Form for WAC Pilot: Plymouth

Wrap Around Childcare (WAC) Plymouth Eligibility and Application form for WAC pilot: Plymouth. Personal data recorded on this form is collected for processing purposes in line with the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR), Article 6(1)(e); Data Protection Act (DPA) 2018. Further details of how the Ministry of Defence processes your personal data can be found at: MOD privacy notice (www) Processing of this data is necessary for application screening and funding approval where applicable. Please note that by completing this form you are consenting to the information contained within it to be used to process your application for Wrap Around Childcare, (WAC). This means that details will be shared with those members of staff who are required to check your eligibility status including your local HR Personnel, (this could also include APC OH in Glasgow and Operational Commitments Establishment (OCE)), the Childcare Support Team and potentially HMRC. The application data will be stored on a secure system, or in the case of a hard copy, (paper), submission the application will be scanned and stored on a secure system with the original being shredded. Due to the requirement to reconfirm eligibility at the three month point then this application data will be retained for as long as you take part in the WAC. The application data will be used to provide statistical data on the uptake of the WAC which will be shared within the MOD and potentially with partner organisations but any data used in this way would not contain personal information other than where required by HMRC. -

The Wedding of His Royal Highness Prince William Of

THE WEDDING OF HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS PRINCE WILLIAM OF WALES, K.G. WITH MISS CATHERINE MIDDLETON 29th APRIL 2011 A SUMMARY OF INFORMATION AS OF 28th APRIL 2011 1 Contents as of 28/04/11 Page ● The Service 3 ● Costs 3 ● Timings 4 ● Members of the Wedding Party 6 ● Invitations 7 ● Selected Guest List for the Wedding Service at Westminster Abbey 8 ● Westminster Abbey Seating Plan 16 ● The Route 19 ● Cars and Carriages 19 ● Music for the Wedding Service 22 ● Wedding Musicians 24 ● Floral Displays 26 ● Wedding Ring 28 ● Receptions 29 ● Wedding Cake 30 ● Official Photographer 31 ● Westminster Abbey 32 ● Ceremonial Bodies 39 ● Official Souvenir Wedding Programme 41 ● New Coat of Arms for Miss Catherine Middleton and her Family 43 ● Instrument of Consent 45 ● Gifts 46 ● Wedding Website 54 ● The Royal Wedding Online – On the day 55 ● Visitors to London 57 ● Ministry of Defence Royal Wedding Commentary 58 ● The Royal Wedding Policing Operation 88 ● Media logistics 91 ● Biographies o Prince William 92 o Catherine Middleton 95 o The Prince of Wales 96 o The Duchess of Cornwall 99 o Prince Harry 100 o Clergy 102 o Organist and Master of the Choristers, Westminster Abbey 105 ● The British Monarchy 106 o The Queen 106 o The Prince of Wales 107 o The Royal Family 108 2 The Service The marriage of Prince William and Miss Catherine Middleton will take place at Westminster Abbey on Friday 29th April 2011. The Dean of Westminster will conduct the service, the Archbishop of Canterbury will marry Prince William and Miss Middleton, and the Bishop of London will give the address. -

Sailing New Waters - Role Two Afloat Medical Facility Enhanced Counter Piracy Operations September – December 2010

J Royal Naval Medical Service 2011, 97.1 21-27 General Sailing new waters - role two afloat medical facility Enhanced counter piracy operations September – December 2010 A L Day, D A Newman, R M Heames, J E Risdall Introduction predominantly on the East coast of Somalia in In Autumn 2010, a Role Two Afloat Medical the Somali Basin [Figure 1]. The aim of Team (R2A), deployed onboard RFA Fort counter piracy operations was to deter and Victoria (FTVR), initially as part of the UK disrupt pirate activity through a show of Enhanced Counter Piracy (ECP) operation, Maritime Force using the assets on board initially Operation Capri under CTF 151 (with FTVR, namely the airpower of the embarked HMS Northumberland) and subsequently Merlin, and the Royal Marine boarding teams under NATO command (CTF 508) on and boats. Operation Ocean Shield with HMS Montrose. This article sets out the background to the The area of operation spanned the North West history of piracy in the Somali Basin and how region of the Indian Ocean, focusing the R2A developed its role on the ship and integrated itself with the other Embarked Military Forces (EMF) to provide support to the anti-piracy operations. Political Background Since 2008, piracy of commercial shipping within the Somali region has escalated, finally coming to a head by the taking of the super tanker MV Sirius Star captured November 2008, 450 miles south-east of Mombasa, Kenya. Once taken it was sailed to an anchorage close to Hobyo, Somalia, a well known pirate camp area. This incident was of international concern especially as the Sirius Star (with 2 UK citizens in the crew) contained a quarter of Saudi Arabia’s daily output of oil and resulted in its price jumping to more than $1 a barrel. -

Inside This Brief Editorial Team Captain Sarabjeet S

Inside this Brief Editorial Team Captain Sarabjeet S. Parmar Maritime Security………………………………p.7 Mr. Oliver N. Gonsalves Maritime Forces………………………………..p.10 Shipping, Ports and Ocean Economy.….p.16 Address Marine Environment………………………...p.25 National Maritime Foundation Geopolitics……………………………………….p.35 Varuna Complex, NH- 8 Airport Road New Delhi-110 010, India Email:[email protected] Acknowledgement : ‘Making Waves’ is a compilation of maritime news and news analyses drawn from national and international online sources. Drawn directly from original sources, minor editorial amendments are made by specialists on maritime affairs. It is intended for academic research, and not for commercial use. NMF expresses its gratitude to all sources of information, which are cited in this publication. Royal Navy makes large drug seizure in Arabian Sea Saudi Arabia joins U.S.-led maritime coalition after attack on its oil facility Page 2 of 37 Japan to independently dispatch MSDF to Middle East Hyundai to design F-35B-capable amphibious assault ship for ROK Navy First UK fighter jets land onboard HMS Queen Elizabeth Philippines, Japan, US conclude amphibious drill Kamandag Russian frigate Admiral Kasatonov begins state trials US leads International Maritime Exercise in Persian Gulf Page 3 of 37 Hambantota International Port partners with NYK Japan LNG shipping rates soar as sanctions hit vessel availability IBM Boards Mayflower Autonomous Ship Project Atlantic container shipping rates far outperform Pacific Australia and European Union push for -

UK Defence from the 'Far East' to the 'Indo-Pacific'

UK Defence from the ‘Far East’ to the ‘Indo-Pacific’ Dr Alessio Patalano Foreword by Rt Hon Sir Michael Fallon MP Endorsements “This is an important contribution to our understanding of a region that is so vital to international peace and security. I find Dr. Patalano’s insights and arguments informative and relevant to any nation with interests in the sustaining the stability of the global order. He makes a striking case that it is important to abandon a backwards looking perspective and instead look forward with insight and vision for a future that is compelling for all.” Admiral Scott Harbison Swift is a retired admiral in the US Navy, former Commander of the US Pacific Fleet and former Director of the Navy Staff on the Office of Chief of Naval Operations Cover image: HMS SUTHERLAND’S wildcat helicopter, callsign ‘FEARLESS’. With the Japanese ship JS SUZUNAMI in the background.. Crown Copyright 2019, reproduced with permission. UK Defence from the ‘Far East’ to the ‘Indo-Pacific’ Dr Alessio Patalano Foreword by Rt Hon Sir Michael Fallon MP Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an independent, non-partisan educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development and retains copyright and full editorial control over all its written research. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes.