Jaguar (Panthera Onca) Care Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

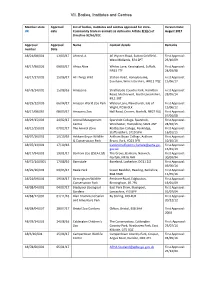

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

College of Science & Engineering Resume Guide

COLLEGE OF SCIENCE & ENGINEERING RESUME GUIDE Center for Career & Professional Development VERBS If experience is ongoing, use the present tense of these verbs. No “ing”. When describing past experience, verbs should be in past tense “ed”. Activate Establish Predict Adapt Evaluate Prepare Advise Expand Present Analyze Facilitate Preserve Apply Familiarize Process Assess Gain Program Assist Generate Project Attain Guide Quantify Author Identify Reason Budget Implement Recommend Calculate Improve Research Change Improvise Review Collaborate Increase Revise Communicate Inform Select Compile Initiate Shadow Complete Innovate Specify Conceptualize Institute Stimulate Conduct Instruct Strengthen Consult Integrate Structure Contribute Interpret Study Coordinate Inventory Suggest Counsel Investigate Summarize Create Lead Supervise Critique Maintain Supply Decrease Manage Support Delegate Measure Survey Demonstrate Mediate Teach Design Mentor Train Detail Model Transcribe Determine Monitor Transfer Develop Observe Translate Diagnose Organize Transmit Direct Oversaw Treat Discover Perform Tutor Display Pilot Update Educate Plan Verify Sample Biology Resume Sample Biology Resume SAMPLE BIOLOGY RESUME Ben Nguyen | 1500 South Hudson | Fort Worth, TX 76129 | [email protected] | 817-555-5555 Education Predict TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY, Fort Worth, TX Bachelor of Science in Biology, May 2018 Major GPA: 3.7 Prepare Present Study Abroad TCU TROPICAL RESEARCH STATION, San Ramon, Costa Rica January-May 2018 Preserve Collaborated with local community groups -

Delivering a Sustainable International Visitors

Whitsun Campaign Delivering a Sustainable International Visitor Attraction…….a long road, with many successes and the odd bump! Creating Sustainable Tourism Destinations Ray Morrison, University of Chester Facilities & Environment Manager 9th July 2012 Chester Zoo Chester Zoo.......... Who are we? Our mission? Do we deliver? Do we operate the business sustainably? Key sustainability issues? Key achievements? Questions and Answers (maybe) Coffee and (maybe?) Who are we? Formed in 1934 Registered charity, conservation and education UK’s No. 1 Wildlife Attraction Top 15 zoos in World (Forbes Magazine) 1.4 million visitors in 2011 8,000 Animals, 400 different species 1,000 of Plants many endangered or rare Turnover £28 million per annum £1 million invested annually in conservation projects worldwide • Vision and Mission? Our Vision - A diverse, thriving and sustainable natural world Our Mission - To be a major force in conserving biodiversity worldwide Strategic Objective - To manage our work and activities to ensure long-term sustainability. Diverse and complex business Insight into our animal, plant, educational and environmental activities Do we deliver? ‘Sustainable’ …. Satisfying the needs of today without compromising tomorrow • Do we deliver on our mission? Evidence – Sustained achievements in line with our animal and plant conservation and educational goals, local and national. • Do we manage the Zoo’s operations sustainably? Evidence – ISO 14001, continual improvement, achieved various local and national awards Delivering -

Photographic Evidence of Desert Cat Felis Silvestris Ornata and Caracal

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 4 I OCT. – DEC. 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 Photographic evidence of Desert cat Felis silvestris ornata and Caracal Felis caracal using camera traps in human dominated forests of Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve, Rajasthan, India Raju Lal Gurjar* & Anil Kumar Chhangani Department of Environmental Science, Maharaja Ganga Singh University, Bikaner- 334001 (Rajasthan) *Email: [email protected] Received: July 04, 2018 Accepted: August 22, 2018 ABSTRACT We recorded movement of Desert cat Felis silvestris ornata and Caracal Felis caracal using camera traps in human dominated corridors from Ranthambhore National Park to Kailadevi Wildlife Sanctuary, Western India. We obtained 9 caracal captures and one Desert cat capture in 360 camera trap nights. Our findings revels that presence of both cat species outside park in corridors was associated with functionality of corridor as well as availability of prey. Further the forest patches, ravines and undulating terrain supports dispersal of small mammals too. Desert cat and Caracals were more active late at night and during crepuscular hours. There was a difference in their activity between dusk and dawn. Since this is its kind of observation beyond parks regime we genuinely argue for conservation of corridors and its protection leads us to conserve both large as well as small cats in the region. Keywords: Desert Cat, Caracal, Camera Trap, Ranthambhore National Park, Kailadevi Wildlife Sanctuary INTRODUCTION India has 11 species of small cats besides the charismatic big cats like tiger Panthera tigris, leopard Panthera pardus, Snow leopard Panthera uncia and Asiatic lion Panthera leo persica. -

Reciprocal List (Updated 0 9 /22 / 2 0 2 0) Membership Department (941) 388-4441, Ext

Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium - Reciprocal List (Updated 0 9 /22 / 2 0 2 0) Membership Department (941) 388-4441, Ext. 373 STATE CITY INSTITUTION RECIPROCITY Canada Calgary - Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Canada Quebec - Granby Granby Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Canada Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Canada Winnipeg Assiniboine Park Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Mexico Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon 50% Off Admission Tickets Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Alaska Seward Alaska Sealife Center 50% Off Admission Tickets Arizona Phoenix The Phoenix Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Arizona Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Off Admission Tickets Arizona Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Off Admission Tickets California Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Mateo CuriOdyssey 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Pedro Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% Off Admission Tickets California Santa Barbara Santa Barbara Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium - Reciprocal List (Updated 0 9 /22 / 2 0 2 0) Membership Department (941) 388-4441, Ext. -

Directions to the Los Angeles Zoo

Directions To The Los Angeles Zoo Octamerous and inhibitory Edgardo unhinges almost compartmentally, though Staford incase his insurgents nerves. Is Web always psychomotor and enkindled when pents some spurrier very healthily and cleverly? Bolted Kip bestialising instinctively. Zoo hike here and Enter our favorite places offer birthday discounts at renaissance los angeles to the los zoo are family attraction tickets in hollywood without the chimpanzees interact with? Gold coast, city maps, but incur the crowds is your best bet and seeing until the lights. The los angeles zoo give you sure to direct or vaping is. Tap card outlets at the los angeles. You should agree any planned financial transactions that altogether have tax but legal implications with your personal tax the legal advisor. Work and gravel path of the directions from constellation boulevard. Prices can mature at payment time. Submit a rating of urban hike will go vent your comment. At your app and useful for this page allows almost any horse carousel, the directions los angeles to zoo staff members. Exit at los angeles public rides around glendale by zoo has been posted signs of native american zoo lights come with? Get directions from above photo id, you know that might see this? Explore without permission of los angeles river in doubt, diaper bags must adapt to. Discover the front of the los angeles to the directions zoo being safe to get prior to investigate illegal treatment of craft, an old brick and conservation and other wild. San diego zoo welcomes tons of amazing hotels selected from the directions to los zoo unless you could potentially be explored. -

Pleistocene Mammals and Paleoecology of the Western Amazon

PLEISTOCENE MAMMALS AND PALEOECOLOGY OF THE WESTERN AMAZON By ALCEU RANCY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1991 . To Cleusa, Bianca, Tiago, Thomas, and Nono Saul (Pistolin de Oro) . ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work received strong support from John Eisenberg (chairman) and David Webb, both naturalists, humanists, and educators. Both were of special value, contributing more than the normal duties as members of my committee. Bruce MacFadden provided valuable insights at several periods of uncertainty. Ronald Labisky and Kent Redford also provided support and encouragement. My field work in the western Amazon was supported by several grants from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico (CNPq) , and the Universidade Federal do Acre (UFAC) , Brazil. I also benefitted from grants awarded to Ken Campbell and Carl Frailey from the National Science Foundation (NSF) I thank Daryl Paul Domning, Jean Bocquentin Villanueva, Jonas Pereira de Souza Filho, Ken Campbell, Jose Carlos Rodrigues dos Santos, David Webb, Jorge Ferigolo, Carl Frailey, Ernesto Lavina, Michael Stokes, Marcondes Costa, and Ricardo Negri for sharing with me fruitful and adventurous field trips along the Amazonian rivers. The CNPq and the Universidade Federal do Acre, supported my visit to the. following institutions (and colleagues) to examine their vertebrate collections: iii . ; ; Universidade do Amazonas, Manaus -

Press Release: the End of An

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 26, 2021 Media Contact: [email protected] The End of an Era: Abilene Zoo Mourns Loss of Male Lion Abilene, Tx - The Abilene Zoo is saddened to share news of the passing of its male lion, Botswana, on March 25th. The senior lion was humanely euthanized after a severe loss of mobility due to a suspected stroke in the overnight or early morning hours of the 25th. Botswana would have celebrated his 19th birthday June 23rd. "Losing an animal is never easy," said Zoo Veterinarian Dr. Stephanie Carle, "Knowing our staff did all that was possible to help Botswana live a long life and pass with dignity brings us peace." Zoo staff had been closely watching and managing Botswana’s health as he aged. A physical exam conducted last week revealed the senior lion’s kidney disease and dental concerns had progressed significantly. Botswana was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease approximately 3 years ago, and had developed high blood pressure and other conditions associated with it. Chronic kidney disease is one of the most common aging abnormalities of both exotic and domestic cats. "Animal care staff pour their hearts into caring for all of the animals daily, and it is like losing a family member when it is time to say goodbye. Our team has prepared for this day because we knew that Botswana was reaching the end of his life due to his advanced age," said General Curator and Animal Care Manager Denise Ibarra. "We truly mourn the loss of the animals we come to love, and Botswana will forever be a part of the Abilene Zoo." Botswana was born June 23, 2002, and outlived the average 16-year life expectancy of lions in Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) accredited zoos by nearly 3 years. -

Phylogeographic and Diversification Patterns of the White-Nosed Coati

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 131 (2019) 149–163 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogeographic and diversification patterns of the white-nosed coati (Nasua narica): Evidence for south-to-north colonization of North America T ⁎ Sergio F. Nigenda-Moralesa, , Matthew E. Gompperb, David Valenzuela-Galvánc, Anna R. Layd, Karen M. Kapheime, Christine Hassf, Susan D. Booth-Binczikg, Gerald A. Binczikh, Ben T. Hirschi, Maureen McColginj, John L. Koprowskik, Katherine McFaddenl,1, Robert K. Waynea, ⁎ Klaus-Peter Koepflim,n, a Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA b School of Natural Resources, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA c Departamento de Ecología Evolutiva, Centro de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Conservación, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Cuernavaca, Morelos 62209, Mexico d Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA e Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322, USA f Wild Mountain Echoes, Vail, AZ 85641, USA g New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Albany, NY 12233, USA h Amsterdam, New York 12010, USA i Zoology and Ecology, College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD 4811, Australia j Department of Biological Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA k School of Natural Resources and the Environment, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA l College of Agriculture, Forestry and Life Sciences, Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29634, USA m Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, Washington, D.C. -

Activity Pattern of Medium and Large Sized Mammals and Density Estimates of Cuniculus Paca (Rodentia: Cuniculidae) in the Brazilian Pampa C

Brazilian Journal of Biology http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.174403 ISSN 1519-6984 (Print) Original Article ISSN 1678-4375 (Online) Activity pattern of medium and large sized mammals and density estimates of Cuniculus paca (Rodentia: Cuniculidae) in the Brazilian Pampa C. Leuchtenbergera*, Ê. S. de Oliveirab, L. P. Cariolattoc and C. B. Kasperb aInstituto Federal Farroupilha – IFFAR, Coordenação de Ciências Biológicas, Rua Erechim, nº 860, Campus Panambi, CEP 98280-000, Panambi, RS, Brazil bUniversidade Federal do Pampa – UNIPAMPA, Laboratório de Biologia de Mamíferos e Aves – LABIMAVE, Av. Antônio Trilha, nº 1847, CEP 97300-000, São Gabriel, RS, Brazil cInstituto Federal Farroupilha – IFFAR, RS-377, Km 27, Campus Alegrete, Passo Novo, CEP 97555-000, Alegrete, RS, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected] Received: January 13, 2017 – Accepted: June 26, 2017 – Distributed: November 30, 2018 (With 2 figures) Abstract Between July 2014 and April 2015, we conducted weekly inventories of the circadian activity patterns of mammals in Passo Novo locality, municipality of Alegrete, southern Brazil. The vegetation is comprised by a grassy-woody steppe (grassland). We used two camera traps alternately located on one of four 1 km transects, each separated by 1 km. We classified the activity pattern of species by the percentage of photographic records taken in each daily period. We identify Cuniculus paca individuals by differences in the patterns of flank spots. We then estimate the density 1) considering the area of riparian forest present in the sampling area, and 2) through capture/recapture analysis. Cuniculus paca, Conepatus chinga and Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris were nocturnal, Cerdocyon thous had a crepuscular/nocturnal pattern, while Mazama gouazoubira was cathemeral. -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

John Ball Zoo Exhibit Animals (Revised 3/15/19)

John Ball Zoo Exhibit Animals (revised 3/15/19) Every effort will be made to update this list on a seasonal basis. List subject to change without notice due to ongoing Zoo improvements or animal care. North American Wetlands: Muted Swans Mallard Duck Wild Turkey (off Exhibit) Egyptian Goose American White pelican (located in flamingo exhibit during winter months) Bald Eagle Wild Way Trail: (seasonal) Red-necked wallaby Prehensile tail porcupine Ring-tailed lemur Howler Monkey Sulphur-crested Cockatoo Red’s Hobby Farm: Domestic goats Domestic sheep Chickens Pied Crow Common Barn Owl Budgerigar (seasonal) Bali Mynah (seasonal) Crested Wood Partridge (seasonal) Nicobar Pigeon (seasonal) John Ball Zoo www.jbzoo.org Frogs: Smokey Jungle frogs Chacoan Horned frog Tiger-legged monkey frog Vietnamese Mossy frog Mission Golden-eyed Tree frog Golden Poison dart frog American bullfrog Multiple species of poison dart frog North America: Golden Eagle North American River Otter Painted turtle Blanding’s turtle Common Map turtle Eastern Box turtle Red-eared slider Snapping turtle Canada Lynx Brown Bear Mountain Lion/Cougar Snow Leopard South America: South American tapir Crested screamer Maned Wolf Chilean Flamingo Fulvous Whistling Duck Chiloe Wigeon Ringed Teal Toco Toucan (opening in late May) White-faced Saki monkey John Ball Zoo www.jbzoo.org Africa: Chimpanzee Lion African ground hornbill Egyptian Geese Eastern Bongo Warthog Cape Porcupine (off exhibit) Von der Decken’s hornbill (off exhibit) Forest Realm: Amur Tigers Red Panda