The Date for the Opening of the Twentieth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Natural Science Underlying Big History

Review Article [Accepted for publication: The Scientific World Journal, v2014, 41 pages, article ID 384912; printed in June 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/384912] The Natural Science Underlying Big History Eric J. Chaisson Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 USA [email protected] Abstract Nature’s many varied complex systems—including galaxies, stars, planets, life, and society—are islands of order within the increasingly disordered Universe. All organized systems are subject to physical, biological or cultural evolution, which together comprise the grander interdisciplinary subject of cosmic evolution. A wealth of observational data supports the hypothesis that increasingly complex systems evolve unceasingly, uncaringly, and unpredictably from big bang to humankind. This is global history greatly extended, big history with a scientific basis, and natural history broadly portrayed across ~14 billion years of time. Human beings and our cultural inventions are not special, unique, or apart from Nature; rather, we are an integral part of a universal evolutionary process connecting all such complex systems throughout space and time. Such evolution writ large has significant potential to unify the natural sciences into a holistic understanding of who we are and whence we came. No new science (beyond frontier, non-equilibrium thermodynamics) is needed to describe cosmic evolution’s major milestones at a deep and empirical level. Quantitative models and experimental tests imply that a remarkable simplicity underlies the emergence and growth of complexity for a wide spectrum of known and diverse systems. Energy is a principal facilitator of the rising complexity of ordered systems within the expanding Universe; energy flows are as central to life and society as they are to stars and galaxies. -

Islamic Calendar from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Islamic calendar From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia -at اﻟﺘﻘﻮﻳﻢ اﻟﻬﺠﺮي :The Islamic, Muslim, or Hijri calendar (Arabic taqwīm al-hijrī) is a lunar calendar consisting of 12 months in a year of 354 or 355 days. It is used (often alongside the Gregorian calendar) to date events in many Muslim countries. It is also used by Muslims to determine the proper days of Islamic holidays and rituals, such as the annual period of fasting and the proper time for the pilgrimage to Mecca. The Islamic calendar employs the Hijri era whose epoch was Islamic Calendar stamp issued at King retrospectively established as the Islamic New Year of AD 622. During Khaled airport (10 Rajab 1428 / 24 July that year, Muhammad and his followers migrated from Mecca to 2007) Yathrib (now Medina) and established the first Muslim community (ummah), an event commemorated as the Hijra. In the West, dates in this era are usually denoted AH (Latin: Anno Hegirae, "in the year of the Hijra") in parallel with the Christian (AD) and Jewish eras (AM). In Muslim countries, it is also sometimes denoted as H[1] from its Arabic form ( [In English, years prior to the Hijra are reckoned as BH ("Before the Hijra").[2 .(ﻫـ abbreviated , َﺳﻨﺔ ﻫِ ْﺠﺮﻳّﺔ The current Islamic year is 1438 AH. In the Gregorian calendar, 1438 AH runs from approximately 3 October 2016 to 21 September 2017.[3] Contents 1 Months 1.1 Length of months 2 Days of the week 3 History 3.1 Pre-Islamic calendar 3.2 Prohibiting Nasī’ 4 Year numbering 5 Astronomical considerations 6 Theological considerations 7 Astronomical -

Geologic History of the Earth 1 the Precambrian

Geologic History of the Earth 1 algae = very simple plants that Geologists are scientists who study the structure grow in or near the water of rocks and the history of the Earth. By looking at first = in the beginning at and examining layers of rocks and the fossils basic = main, important they contain they are able to tell us what the beginning = start Earth looked like at a certain time in history and billion = a thousand million what kind of plants and animals lived at that breathe = to take air into your lungs and push it out again time. carbon dioxide = gas that is produced when you breathe Scientists think that the Earth was probably formed at the same time as the rest out of our solar system, about 4.6 billion years ago. The solar system may have be- certain = special gun as a cloud of dust, from which the sun and the planets evolved. Small par- complex = something that has ticles crashed into each other to create bigger objects, which then turned into many different parts smaller or larger planets. Our Earth is made up of three basic layers. The cen- consist of = to be made up of tre has a core made of iron and nickel. Around it is a thick layer of rock called contain = have in them the mantle and around that is a thin layer of rock called the crust. core = the hard centre of an object Over 4 billion years ago the Earth was totally different from the planet we live create = make on today. -

Critical Analysis of Article "21 Reasons to Believe the Earth Is Young" by Jeff Miller

1 Critical analysis of article "21 Reasons to Believe the Earth is Young" by Jeff Miller Lorence G. Collins [email protected] Ken Woglemuth [email protected] January 7, 2019 Introduction The article by Dr. Jeff Miller can be accessed at the following link: http://apologeticspress.org/APContent.aspx?category=9&article=5641 and is an article published by Apologetic Press, v. 39, n.1, 2018. The problems start with the Article In Brief in the boxed paragraph, and with the very first sentence. The Bible does not give an age of the Earth of 6,000 to 10,000 years, or even imply − this is added to Scripture by Dr. Miller and other young-Earth creationists. R. C. Sproul was one of evangelicalism's outstanding theologians, and he stated point blank at the Legionier Conference panel discussion that he does not know how old the Earth is, and the Bible does not inform us. When there has been some apparent conflict, either the theologians or the scientists are wrong, because God is the Author of the Bible and His handiwork is in general revelation. In the days of Copernicus and Galileo, the theologians were wrong. Today we do not know of anyone who believes that the Earth is the center of the universe. 2 The last sentence of this "Article In Brief" is boldly false. There is almost no credible evidence from paleontology, geology, astrophysics, or geophysics that refutes deep time. Dr. Miller states: "The age of the Earth, according to naturalists and old- Earth advocates, is 4.5 billion years. -

Confronting History on Campus

CHRONICLEFocusFocus THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION Confronting History on Campus As a Chronicle of Higher Education individual subscriber, you receive premium, unrestricted access to the entire Chronicle Focus collection. Curated by our newsroom, these booklets compile the most popular and relevant higher-education news to provide you with in-depth looks at topics affecting campuses today. The Chronicle Focus collection explores student alcohol abuse, racial tension on campuses, and other emerging trends that have a significant impact on higher education. ©2016 by The Chronicle of Higher Education Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, forwarded (even for internal use), hosted online, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For bulk orders or special requests, contact The Chronicle at [email protected] ©2016 THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS OODROW WILSON at Princeton, John Calhoun at Yale, Jefferson Davis at the University of Texas at Austin: Students, campus officials, and historians are all asking the question, What’sW in a name? And what is a university’s responsibil- ity when the name on a statue, building, or program on campus is a painful reminder of harm to a specific racial group? Universities have been grappling anew with those questions, and trying different approaches to resolve them. Colleges Struggle Over Context for Confederate Symbols 4 The University of Mississippi adds a plaque to a soldier’s statue to explain its place there. -

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

How Long Is a Year.Pdf

How Long Is A Year? Dr. Bryan Mendez Space Sciences Laboratory UC Berkeley Keeping Time The basic unit of time is a Day. Different starting points: • Sunrise, • Noon, • Sunset, • Midnight tied to the Sun’s motion. Universal Time uses midnight as the starting point of a day. Length: sunrise to sunrise, sunset to sunset? Day Noon to noon – The seasonal motion of the Sun changes its rise and set times, so sunrise to sunrise would be a variable measure. Noon to noon is far more constant. Noon: time of the Sun’s transit of the meridian Stellarium View and measure a day Day Aday is caused by Earth’s motion: spinning on an axis and orbiting around the Sun. Earth’s spin is very regular (daily variations on the order of a few milliseconds, due to internal rearrangement of Earth’s mass and external gravitational forces primarily from the Moon and Sun). Synodic Day Noon to noon = synodic or solar day (point 1 to 3). This is not the time for one complete spin of Earth (1 to 2). Because Earth also orbits at the same time as it is spinning, it takes a little extra time for the Sun to come back to noon after one complete spin. Because the orbit is elliptical, when Earth is closest to the Sun it is moving faster, and it takes longer to bring the Sun back around to noon. When Earth is farther it moves slower and it takes less time to rotate the Sun back to noon. Mean Solar Day is an average of the amount time it takes to go from noon to noon throughout an orbit = 24 Hours Real solar day varies by up to 30 seconds depending on the time of year. -

The Little Metropolis at Athens 15

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2011 The Littleetr M opolis: Religion, Politics, & Spolia Paul Brazinski Bucknell University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Brazinski, Paul, "The Little eM tropolis: Religion, Politics, & Spolia" (2011). Honors Theses. 12. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/12 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Paul A. Brazinski iv Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge and thank Professor Larson for her patience and thoughtful insight throughout the writing process. She was a tremendous help in editing as well, however, all errors are mine alone. This endeavor could not have been done without you. I would also like to thank Professor Sanders for showing me the fruitful possibilities in the field of Frankish archaeology. I wish to thank Professor Daly for lighting the initial spark for my classical and byzantine interests as well as serving as my archaeological role model. Lastly, I would also like to thank Professor Ulmer, Professor Jones, and all the other Professors who have influenced me and made my stay at Bucknell University one that I will never forget. This thesis is dedicated to my Mom, Dad, Brian, Mark, and yes, even Andrea. Paul A. Brazinski v Table of Contents Abstract viii Introduction 1 History 3 Byzantine Architecture 4 The Little Metropolis at Athens 15 Merbaka 24 Agioi Theodoroi 27 Hagiography: The Saints Theodores 29 Iconography & Cultural Perspectives 35 Conclusions 57 Work Cited 60 Appendix & Figures 65 Paul A. -

Vaughn Next Century Learning Center

2020 VAUGHN 2021 NEXT CENTURY LEARNING CENTER July/julio 2020 JULY-JULIO January/enero 2021 S M T W Th F S 1-31 Summer Vacation S M T W Th F S 1 2 3 4 30-31 Staff Development 1 2 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 3 SPED SPED SPED ESY ESY 9 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 AUGUST-AGOSTO 10 ESY ESY ESY ESY ESY 16 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 1 Compact Signing 17 18 ESY ESY ESY ESY 23 26 27 28 29 SD SD 3 Staff Development 24 ESY ESY ESY ESY SPED 30 0 4 FIRST DAY OF SCHOOL 31 August/agosto 2020 0 S M T W Th F S SEPTEMBER-SEPTIEMBRE February/febrero 2021 CS 4 Minimum Day (Comp Time) S M T W Th F S 2 SD 4 5 6 7 8 7 Labor Day Holiday SD 2 3 4 5 6 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 OCTOBER-OCTUBRE 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 5-9 Fall Break 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 30 31 28 20 NOVEMBER-NOVIEMBRE 18 September/septiembre 2020 3 Election Day - No Committee Meeting March/marzo 2021 S M T W Th F S 11 Veteran's Day Holiday S M T W Th F S 1 2 3 4 5 25 Minimum Day (Comp Time) 1 2 3 4 5 6 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 26-27 Thanksgiving Day Holiday 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 DECEMBER-DICIEMBRE 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 27 28 29 30 17 Minimum Day 28 29 30 31 21 18-31 Winter Vacation 20 October/octubre 2020 April/abril 2021 S M T W Th F S JANUARY-ENERO S M T W Th F S 1 2 3 1-6 Winter Vacation 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 4-6, 29 SpEd ESY (ID'd SPED Only) 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 7-28 ESY 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 18 Martin Luther King Jr Holiday 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 No School (Except -

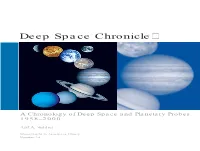

Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: a Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 | Asifa

dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 1 Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: A Chronology ofDeep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 |Asif A.Siddiqi National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA SP-2002-4524 A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 Asif A. Siddiqi NASA SP-2002-4524 Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 2 Cover photo: A montage of planetary images taken by Mariner 10, the Mars Global Surveyor Orbiter, Voyager 1, and Voyager 2, all managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Included (from top to bottom) are images of Mercury, Venus, Earth (and Moon), Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. The inner planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth and its Moon, and Mars) and the outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) are roughly to scale to each other. NASA SP-2002-4524 Deep Space Chronicle A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 ASIF A. SIDDIQI Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 June 2002 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of External Relations NASA History Office Washington, DC 20546-0001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siddiqi, Asif A., 1966 Deep space chronicle: a chronology of deep space and planetary probes, 1958-2000 / by Asif A. Siddiqi. p.cm. – (Monographs in aerospace history; no. 24) (NASA SP; 2002-4524) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Space flight—History—20th century. I. Title. II. Series. III. NASA SP; 4524 TL 790.S53 2002 629.4’1’0904—dc21 2001044012 Table of Contents Foreword by Roger D. -

Package 'Lubridate'

Package ‘lubridate’ February 26, 2021 Type Package Title Make Dealing with Dates a Little Easier Version 1.7.10 Maintainer Vitalie Spinu <[email protected]> Description Functions to work with date-times and time-spans: fast and user friendly parsing of date-time data, extraction and updating of components of a date-time (years, months, days, hours, minutes, and seconds), algebraic manipulation on date-time and time-span objects. The 'lubridate' package has a consistent and memorable syntax that makes working with dates easy and fun. Parts of the 'CCTZ' source code, released under the Apache 2.0 License, are included in this package. See <https://github.com/google/cctz> for more details. License GPL (>= 2) URL https://lubridate.tidyverse.org, https://github.com/tidyverse/lubridate BugReports https://github.com/tidyverse/lubridate/issues Depends methods, R (>= 3.2) Imports generics, Rcpp (>= 0.12.13) Suggests covr, knitr, testthat (>= 2.1.0), vctrs (>= 0.3.0), rmarkdown Enhances chron, timeDate, tis, zoo LinkingTo Rcpp VignetteBuilder knitr Encoding UTF-8 LazyData true RoxygenNote 7.1.1 SystemRequirements A system with zoneinfo data (e.g. /usr/share/zoneinfo) as well as a recent-enough C++11 compiler (such as g++-4.8 or later). On Windows the zoneinfo included with R is used. 1 2 R topics documented: Collate 'Dates.r' 'POSIXt.r' 'RcppExports.R' 'util.r' 'parse.r' 'timespans.r' 'intervals.r' 'difftimes.r' 'durations.r' 'periods.r' 'accessors-date.R' 'accessors-day.r' 'accessors-dst.r' 'accessors-hour.r' 'accessors-minute.r' 'accessors-month.r' -

International Standard Iso 8601-1:2019(E)

This preview is downloaded from www.sis.se. Buy the entire standard via https://www.sis.se/std-80010314 INTERNATIONAL ISO STANDARD 8601-1 First edition 2019-02 Date and time — Representations for information interchange — Part 1: Basic rules Date et heure — Représentations pour l'échange d'information — Partie 1: Règles de base Reference number ISO 8601-1:2019(E) © ISO 2019 This preview is downloaded from www.sis.se. Buy the entire standard via https://www.sis.se/std-80010314 ISO 8601-1:2019(E) COPYRIGHT PROTECTED DOCUMENT © ISO 2019 All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, or required in the context of its implementation, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address belowCP 401or ISO’s • Ch. member de Blandonnet body in 8 the country of the requester. ISO copyright office Phone: +41 22 749 01 11 CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva Fax:Website: +41 22www.iso.org 749 09 47 PublishedEmail: [email protected] Switzerland ii © ISO 2019 – All rights reserved This preview is downloaded from www.sis.se. Buy the entire standard via https://www.sis.se/std-80010314 ISO 8601-1:2019(E) Contents Page Foreword ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................v