Multiple Isotope Effects As a Probe of the Tartrate Dehydrogenase

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

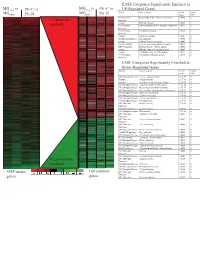

Supplement 1 Microarray Studies

EASE Categories Significantly Enriched in vs MG vs vs MGC4-2 Pt1-C vs C4-2 Pt1-C UP-Regulated Genes MG System Gene Category EASE Global MGRWV Pt1-N RWV Pt1-N Score FDR GO Molecular Extracellular matrix cellular construction 0.0008 0 110 genes up- Function Interpro EGF-like domain 0.0009 0 regulated GO Molecular Oxidoreductase activity\ acting on single dono 0.0015 0 Function GO Molecular Calcium ion binding 0.0018 0 Function Interpro Laminin-G domain 0.0025 0 GO Biological Process Cell Adhesion 0.0045 0 Interpro Collagen Triple helix repeat 0.0047 0 KEGG pathway Complement and coagulation cascades 0.0053 0 KEGG pathway Immune System – Homo sapiens 0.0053 0 Interpro Fibrillar collagen C-terminal domain 0.0062 0 Interpro Calcium-binding EGF-like domain 0.0077 0 GO Molecular Cell adhesion molecule activity 0.0105 0 Function EASE Categories Significantly Enriched in Down-Regulated Genes System Gene Category EASE Global Score FDR GO Biological Process Copper ion homeostasis 2.5E-09 0 Interpro Metallothionein 6.1E-08 0 Interpro Vertebrate metallothionein, Family 1 6.1E-08 0 GO Biological Process Transition metal ion homeostasis 8.5E-08 0 GO Biological Process Heavy metal sensitivity/resistance 1.9E-07 0 GO Biological Process Di-, tri-valent inorganic cation homeostasis 6.3E-07 0 GO Biological Process Metal ion homeostasis 6.3E-07 0 GO Biological Process Cation homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Biological Process Cell ion homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Biological Process Ion homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Molecular Helicase activity 2.3E-06 0 Function GO Biological -

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information (a) (b) Figure S1. Resistant (a) and sensitive (b) gene scores plotted against subsystems involved in cell regulation. The small circles represent the individual hits and the large circles represent the mean of each subsystem. Each individual score signifies the mean of 12 trials – three biological and four technical. The p-value was calculated as a two-tailed t-test and significance was determined using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure; false discovery rate was selected to be 0.1. Plots constructed using Pathway Tools, Omics Dashboard. Figure S2. Connectivity map displaying the predicted functional associations between the silver-resistant gene hits; disconnected gene hits not shown. The thicknesses of the lines indicate the degree of confidence prediction for the given interaction, based on fusion, co-occurrence, experimental and co-expression data. Figure produced using STRING (version 10.5) and a medium confidence score (approximate probability) of 0.4. Figure S3. Connectivity map displaying the predicted functional associations between the silver-sensitive gene hits; disconnected gene hits not shown. The thicknesses of the lines indicate the degree of confidence prediction for the given interaction, based on fusion, co-occurrence, experimental and co-expression data. Figure produced using STRING (version 10.5) and a medium confidence score (approximate probability) of 0.4. Figure S4. Metabolic overview of the pathways in Escherichia coli. The pathways involved in silver-resistance are coloured according to respective normalized score. Each individual score represents the mean of 12 trials – three biological and four technical. Amino acid – upward pointing triangle, carbohydrate – square, proteins – diamond, purines – vertical ellipse, cofactor – downward pointing triangle, tRNA – tee, and other – circle. -

VIEW Open Access the Role of Ubiquitination and Deubiquitination in Cancer Metabolism Tianshui Sun1, Zhuonan Liu2 and Qing Yang1*

Sun et al. Molecular Cancer (2020) 19:146 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-020-01262-x REVIEW Open Access The role of ubiquitination and deubiquitination in cancer metabolism Tianshui Sun1, Zhuonan Liu2 and Qing Yang1* Abstract Metabolic reprogramming, including enhanced biosynthesis of macromolecules, altered energy metabolism, and maintenance of redox homeostasis, is considered a hallmark of cancer, sustaining cancer cell growth. Multiple signaling pathways, transcription factors and metabolic enzymes participate in the modulation of cancer metabolism and thus, metabolic reprogramming is a highly complex process. Recent studies have observed that ubiquitination and deubiquitination are involved in the regulation of metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells. As one of the most important type of post-translational modifications, ubiquitination is a multistep enzymatic process, involved in diverse cellular biological activities. Dysregulation of ubiquitination and deubiquitination contributes to various disease, including cancer. Here, we discuss the role of ubiquitination and deubiquitination in the regulation of cancer metabolism, which is aimed at highlighting the importance of this post-translational modification in metabolic reprogramming and supporting the development of new therapeutic approaches for cancer treatment. Keywords: Ubiquitination, Deubiquitination, Cancer, Metabolic reprogramming Background cells have aroused increasing attention and interest [3]. Metabolic pathways are of vital importance in proliferat- Because of the generality of metabolic alterations in can- ing cells to meet their demands of various macromole- cer cells, metabolic reprogramming is thought as hall- cules and energy [1]. Compared with normal cells, mark of cancer, providing basis for tumor diagnosis and cancer cells own malignant properties, such as increased treatment [1]. For instance, the application of 18F- proliferation rate, and reside in environments short of deoxyglucose positron emission tomography is based on oxygen and nutrient. -

Genome-Scale Metabolic Network Analysis and Drug Targeting of Multi-Drug Resistant Pathogen Acinetobacter Baumannii AYE

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Molecular BioSystems. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2017 Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) for Molecular BioSystems Genome-scale metabolic network analysis and drug targeting of multi-drug resistant pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii AYE Hyun Uk Kim, Tae Yong Kim and Sang Yup Lee* E-mail: [email protected] Supplementary Table 1. Metabolic reactions of AbyMBEL891 with information on their genes and enzymes. Supplementary Table 2. Metabolites participating in reactions of AbyMBEL891. Supplementary Table 3. Biomass composition of Acinetobacter baumannii. Supplementary Table 4. List of 246 essential reactions predicted under minimal medium with succinate as a sole carbon source. Supplementary Table 5. List of 681 reactions considered for comparison of their essentiality in AbyMBEL891 with those from Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1. Supplementary Table 6. List of 162 essential reactions predicted under arbitrary complex medium. Supplementary Table 7. List of 211 essential metabolites predicted under arbitrary complex medium. AbyMBEL891.sbml Genome-scale metabolic model of Acinetobacter baumannii AYE, AbyMBEL891, is available as a separate file in the format of Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) version 2. Supplementary Table 1. Metabolic reactions of AbyMBEL891 with information on their genes and enzymes. Highlighed (yellow) reactions indicate that they are not assigned with genes. No. Metabolism EC Number ORF Reaction Enzyme R001 Glycolysis/ Gluconeogenesis 5.1.3.3 ABAYE2829 -

Table S1. the Statistical Metrics for Key Differentially Expressed Genes (Degs)

Table S1. The statistical metrics for key differentially expressed genes (DEGs) Gene Agilent Id Symbol logFC pValue FDR tvalue Regulation Gene Name oxidized low density lipoprotein A_24_P124624 OLR1 2.458429 1.19E-13 7.25E-10 24.04241 Up receptor 1 A_23_P90273 CHST8 2.622464 3.85E-12 6.96E-09 19.05867 Up carbohydrate sulfotransferase 8 A_23_P217528 KLF8 2.109007 4.85E-12 7.64E-09 18.76234 Up Kruppel like factor 8 A_23_P114740 CFH 2.651636 1.85E-11 1.79E-08 17.13652 Up complement factor H A_23_P34031 XAGE2 2.000935 2.04E-11 1.81E-08 17.02457 Up X antigen family member 2 A_23_P27332 TCF4 1.613097 2.32E-11 1.87E-08 16.87275 Up transcription factor 4 histone cluster 1 H1 family A_23_P250385 HIST1H1B 2.298658 2.47E-11 1.87E-08 16.80362 Up member b abnormal spindle microtubule A_33_P3288159 ASPM 2.162032 2.79E-11 2.01E-08 16.66292 Up assembly H19, imprinted maternally expressed transcript (non-protein A_24_P52697 H19 1.499364 4.09E-11 2.76E-08 16.23387 Up coding) potassium voltage-gated channel A_24_P31627 KCNB1 2.289689 6.65E-11 3.97E-08 15.70253 Up subfamily B member 1 A_23_P214168 COL12A1 2.155835 7.59E-11 4.15E-08 15.56005 Up collagen type XII alpha 1 chain A_33_P3271341 LOC388282 2.859496 7.61E-11 4.15E-08 15.55704 Up uncharacterized LOC388282 A_32_P150891 DIAPH3 2.2068 7.83E-11 4.22E-08 15.5268 Up diaphanous related formin 3 zinc finger protein 185 with LIM A_23_P11025 ZNF185 1.385721 8.74E-11 4.59E-08 15.41041 Up domain heat shock protein family B A_23_P96872 HSPB11 1.887166 8.94E-11 4.64E-08 15.38599 Up (small) member 11 A_23_P107454 -

SUPPORTING INFORMATION for Regulation of Gene Expression By

SUPPORTING INFORMATION for Regulation of gene expression by the BLM helicase correlates with the presence of G4 motifs Giang Huong Nguyen1,2, Weiliang Tang3, Ana I. Robles1, Richard P. Beyer4, Lucas T. Gray5, Judith A. Welsh1, Aaron J. Schetter1, Kensuke Kumamoto1,6, Xin Wei Wang1, Ian D. Hickson2,7, Nancy Maizels5, 3,8 1 Raymond J. Monnat, Jr. and Curtis C. Harris 1Laboratory of Human Carcinogenesis, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, U.S.A; 2Department of Medical Oncology, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, John Radcliffe Hospital, University of Oxford, Oxford, U.K.; 3Department of Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA U.S.A.; 4 Center for Ecogenetics and Environmental Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA U.S.A.; 5Department of Immunology and Department of Biochemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA U.S.A.; 6Department of Organ Regulatory Surgery, Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima, Japan; 7Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Nordea Center for Healthy Aging, University of Copenhagen, Denmark; 8Department of Genome Sciences, University of WA, Seattle, WA U.S.A. SI Index: Supporting Information for this manuscript includes the following 19 items. A more detailed Materials and Methods section is followed by 18 Tables and Figures in order of their appearance in the manuscript text: 1) SI Materials and Methods 2) Figure S1. Study design and experimental workflow. 3) Figure S2. Immunoblot verification of BLM depletion from human fibroblasts. 4) Figure S3. PCA of mRNA and miRNA expression in BLM-depleted human fibroblasts. 5) Figure S4. qPCR confirmation of mRNA array data. 6) Table S1. BS patient and control detail. -

Substrate Softness Promotes Terminal Differentiation of Human

Substrate softness promotes terminal differentiation of human keratinocytes without altering their ability to proliferate back into a rigid environment Choua Ya, Mariana Carrancá, Dominique Sigaudo-Roussel, Philippe Faure, Berengere Fromy, Romain Debret To cite this version: Choua Ya, Mariana Carrancá, Dominique Sigaudo-Roussel, Philippe Faure, Berengere Fromy, et al.. Substrate softness promotes terminal differentiation of human keratinocytes without altering their ability to proliferate back into a rigid environment. Archives of Dermatological Research, Springer Verlag, 2019, 311 (10), pp.741-751. 10.1007/s00403-019-01962-5. hal-02322166 HAL Id: hal-02322166 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02322166 Submitted on 7 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Substrate softness promotes terminal differentiation of human keratinocytes without altering their ability to proliferate back into a rigid environment Choua Ya1,2, Mariana Carrancá1, Dominique Sigaudo-Roussel1, Philippe Faure3, Bérengère Fromy1†, Romain Debret1†* 1 CNRS, University Lyon 1, UMR 5305, Laboratory of Tissue Biology and Therapeutic Engineering, IBCP, 7 Passage du Vercors, 69367 Lyon Cedex 07, France. 2 Isispharma, 29 Rue Maurice Flandin, 69003 Lyon, France. 3 Alpol Cosmétique, 140 Rue Pasteur, 01500 Château-Gaillard, France. -

Gene Expression Patterns Induced by HPV-16 L1 Virus-Like Particles in Leukocytes from Vaccine Recipients

Gene Expression Patterns Induced by HPV-16 L1 Virus-Like Particles in Leukocytes from Vaccine Recipients This information is current as Alfonso J. García-Piñeres, Allan Hildesheim, Lori Dodd, of October 3, 2021. Troy J. Kemp, Jun Yang, Brandie Fullmer, Clayton Harro, Douglas R. Lowy, Richard A. Lempicki and Ligia A. Pinto J Immunol 2009; 182:1706-1729; ; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1706 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/182/3/1706 Downloaded from Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2009/01/15/182.3.1706.DC1 Material http://www.jimmunol.org/ References This article cites 53 articles, 16 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/182/3/1706.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists by guest on October 3, 2021 • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2009 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology Gene Expression Patterns Induced by HPV-16 L1 Virus-Like Particles in Leukocytes from Vaccine Recipients1 Alfonso J. -

1471-2164-6-174-S4.PDF (299.1Kb)

Sup_Table_2. Comparison of the whole genomes in Fig. 3A. Segment 1- Conserved in Bm, Bp, and Bt to Bp to Bt Gene Description % length % identity % length % identity BMA0001 chromosomal replication initiator protein DnaA 100 99 100 96 BMA0002 DNA polymerase III, beta subunit 100 100 100 99 BMA0003 DNA gyrase, B subunit 100 100 100 99 BMA0006 carboxymuconolactone decarboxylase family protein 100 98 100 99 BMA0010 hypothetical protein 100 99 100 92 BMA0011 hypothetical protein 100 100 100 91 BMA0014.1 hypothetical protein 100 99 96 94 BMA0018 hypothetical protein 100 99 100 95 BMA0019 FHA domain protein 100 100 100 94 BMA0020 protein kinase domain protein 100 99 100 90 BMA0023 conserved hypothetical protein 100 99 100 90 BMA0024 aldolase, class II 100 98 100 91 BMA0027 polysaccharide biosynthesis family protein 100 100 100 96 BMA0028 glycosyl transferase, group 1 family protein 100 99 100 94 BMA0029 mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase/mannose-6-phosphate isomerase 100 99 100 92 BMA0030 ElaA family protein 100 99 100 90 BMA0032 glycosyl transferase, group 1 family protein 100 99 100 93 BMA0037 sigma-54 dependent transcriptional regulator 100 99 100 97 BMA0039 beta-mannosidase-related protein 100 99 100 91 BMA0040 conserved hypothetical protein 100 100 100 94 BMA0041 conserved hypothetical protein 100 99 100 95 BMA0042 acyl-CoA dehydrogenase domain protein 100 99 100 96 BMA0043 acyl carrier protein, putative 100 100 100 95 BMA0044 conserved hypothetical protein 100 99 100 96 BMA0045 conserved hypothetical protein 100 100 100 98 BMA0046 -

All Enzymes in BRENDA™ the Comprehensive Enzyme Information System

All enzymes in BRENDA™ The Comprehensive Enzyme Information System http://www.brenda-enzymes.org/index.php4?page=information/all_enzymes.php4 1.1.1.1 alcohol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.B1 D-arabitol-phosphate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.2 alcohol dehydrogenase (NADP+) 1.1.1.B3 (S)-specific secondary alcohol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.3 homoserine dehydrogenase 1.1.1.B4 (R)-specific secondary alcohol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.4 (R,R)-butanediol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.5 acetoin dehydrogenase 1.1.1.B5 NADP-retinol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.6 glycerol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.7 propanediol-phosphate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.8 glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (NAD+) 1.1.1.9 D-xylulose reductase 1.1.1.10 L-xylulose reductase 1.1.1.11 D-arabinitol 4-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.12 L-arabinitol 4-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.13 L-arabinitol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.14 L-iditol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.15 D-iditol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.16 galactitol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.17 mannitol-1-phosphate 5-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.18 inositol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.19 glucuronate reductase 1.1.1.20 glucuronolactone reductase 1.1.1.21 aldehyde reductase 1.1.1.22 UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.23 histidinol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.24 quinate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.25 shikimate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.26 glyoxylate reductase 1.1.1.27 L-lactate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.28 D-lactate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.29 glycerate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.30 3-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.31 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.32 mevaldate reductase 1.1.1.33 mevaldate reductase (NADPH) 1.1.1.34 hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase (NADPH) 1.1.1.35 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA -

Table Legend

Bin 1 Bins 2 & 3 Bins 4 & 5 Bins 6 & 7 Bin 8 Bin 9 Bin 10 Accession Accession Accession Accession Accession Accession Accession Gene Name Gene Name Gene Name Gene Name Gene Name Gene Name Gene Name Number Number Number Number Number Number Number U70270 Mud-4 U70268 Mud-7 H31839 EST (Bak1) BCL2-antagonist/killer 1 U77829 Gas-5 growth arrest homolog AF025670 Caspase 6 (CASP6); MCH2 AA800243 EST (CIDE-A) Cell death inducing DNA fragmenta AA859938 EST (Bnip23l) BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-inte AA818072 EST Bcl-2 associated death agonist AJ006971 DAP-like kinase U77829 Gas-5 growth arrest homolog U77933 Nedd2/Ich-1 M64733 Testosterone-repressed prostate message 2 AA891842 EST Death rec 6, (TNFRSF21) tumor necrosis fa U72995 MAP-kinase activating death domain AA891933 EST Smac protein, mitochondrial precursor, (seconU94340 ADP-ribosyltransferase (NAD+; poly (ADP-ribose) U47315 R2 cerebellum DDRT-T-PCR AA875455 EST Wig1, p53-activated gene 608 U05989 Par-4 induced by effectors of apoptosis AA874794 EST (TNFRSF16) NGF receptor associated protein AA848545 EST Programmed cell death 10, TF-1 cell apoptosi AA874794 EST (TNFRSF16) NGF receptor associated protein U49930 Caspase 3, apoptosis related cysteine protease (IC U49930 Caspase 3, apoptosis related cysteine protease (IC U84410 Caspase 3, apoptosis related cysteine protease (IC AA891591 EST Programmed cell death 8 (apoptosis-inducing AA892388 EST Death-associated kinase 2 AF030358 Chemokine CX3C AA818894 EST (Pgsg) proteoglycan peptide core protein S79676 IL-1 Beta converting enzyme U14647 Interleukin -

Integrative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Common Molecular Subclasses of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Supplementary Information Hoshida, et al., Integrative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Common Molecular Subclasses of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Data analysis Preprocess of microarray datasets: Non-HCC and replicated samples were removed based on the sample annotation attached to each dataset. To integrate the datasets generated by different microarray platforms, each probe ID was converted and collapsed into gene symbols (http://www.genenames.org/) by averaging the signal intensities. For Affymetrix GeneChip datasets, only probe sets with a minimal 3-fold differential expression and absolute difference >100 units across the samples were included (after applying floor and ceiling values of 20 and 16000 units, respectively). Gene filtering for two-channel cDNA array datasets was based on a minimal 2-fold differential expression across the samples and an absolute fold change >2. In addition, only genes having missing values in less than 20% of the samples were included. Missing values were imputated using a k-nearest neighbor algorithm (1) (ImuputeMissingValues module, GenePattern). Identification of common HCC subclasses: i) Subclass Mapping (SubMap) Subclass Mapping (SubMap) was used to identify corresponding subclasses between the training datasets (2). The subclasses to be mapped (candidate subclasses) were defined in each dataset before collapsing into gene symbols using three unsupervised clustering methods: hierarchical clustering (HC, http://biosun1.harvard.edu/complab/dchip/), non- negative matrix factorization (3) (NMF, http://www.broad.mit.edu/cgi- bin/cancer/publications/pub_paper.cgi?mode=view&paper_id=89) and k-means clustering (kmeans function of Matlab software, Mathworks). For the dendrogram generated by HC, the subclass splitting was traced from its root and splitting was allowed if each resulting subclass contained at least 10% of the samples in the dataset.