Andrew Jackson(2000)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corrupt Bargain" Charge Against Clay and Adams

THE "CORRUPT BARGAIN" CHARGE AGAINST CLAY AND ADAMS: AN HISTORIOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS BY WILLIAM G. MORGAN Oral Roberts University Tulsa, Oklahoma The election of 1824 provided a substantial portion of the ground- work for the notable political changes which emerged from the some- what misnamed "Era of Good Feelings," while at the same time involv- ing several unusual political phenomena. A cardinal feature of this electoral struggle was the large number of prominent candidates. Early in the contest the serious contenders totaled as many as "16 or 17," in- cluding William H. Crawford, Secretary of the Treasury; John Quincy Adams, Secretary of State; Henry Clay, long-time Speaker of the House; John C. Calhoun, Secretary of War; Smith Thompson, Secretary of the Navy; Vice-President Daniel D. Tompkins; Governor DeWitt Clinton of New York; Representative William Lowndes of South Carolina; and a comparative latecomer to politics, General Andrew Jackson] As the campaign progressed, several of these men dropped from conten- tion: Lowndes died in 1822, while Thompson, Tompkins, and Clinton fell from the ranks for lack of support, though there was mention of the latter's possible candidacy late in 1823.2 Calhoun subsequently withdrew from the race, deciding to delay his bid for the presidency to accept the second office.8 Of the prominent contenders remaining in the contest, Crawford was the administration favorite, and his position as Treasury Secretary had enabled him to build a significant following in various circles.4 Despite these advantages, Crawford's success proved illusory: among other difficulties, the Georgian suffered a severe stroke in the summer of 1823 and was the victim of the growing antagonism toward the caucus, the very insti- nation on which he was relying to bring him broad party support.5 Adams, Clay, and Jackson fought actively to secure an electoral majority or, failing that, to gain sufficient votes to be included in the top three who would be presented to the House of Representatives for the final decision. -

The Corrupt Bargain

The Corrupt Bargain Thematic Unit Introduction Drama! Intrigue! Scandal! The Presidential Election of 1824 was the most hotly-contested election in American history to that time. Join Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage, Home of the People’s President, in an interactive look at the election that changed the course of American history, examining the question of whether or not our nation is a republic, or a democracy. By referencing primary source documents such as the diary of John Quincy Adams, the official record of the electoral vote, the vote in the House of Representatives and personal letters from Andrew Jackson, students will be able to see a Revolutionary nation come into its own. Objectives A. Examine historical information from a variety of sources, including museum and library collections, letters, maps, government documents, oral histories, firsthand accounts, and web sites. B. Analyze documentation to uncover the events of the Presidential Election of 1824. C. Understand, through dialogue and discussion, how the Presidential Election of 1824 reflected the political climate of the era, its effect on John Quincy Adams’ presidency, and the future of American politics. Background A former cabinet member and Senator. The Speaker of the House of Representatives. A well-travelled international diplomat and the son of a Founding Father. An Indian- fighter, duelist, and powerhouse in Western politics. The Election of 1824 was the first election to that time in which there was not a majority of votes earned by a candidate. As a result, the election moved to the House of Representatives, where each state received one vote. John Quincy Adams, despite being outgained by almost 40,000 votes, won the presidency, and the campaign for the election of 1828 began almost immediately after claims from Jackson supporters alleged a “corrupt bargain” between Adams and Speaker of the House Henry Clay. -

Methods and Philosophies of Managing American Presidential Scandals

Public Disgrace: Methods and Philosophies of Managing American Presidential Scandals Travis Pritchett Pritchett !1 Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................................2 Corruption and Indiscretion: the Election of 1884........................................................................7 "Corrupt Bargain": A Phantom Scandal.......................................................................................11 Scandals of Abraham Lincoln: Insufficiently White Supremacist...............................................15 Scandals of Richard Nixon: Funding and Watergate...................................................................19 Conclusion...................................................................................................................................24 Bibliography.................................................................................................................................27 Pritchett !2 The study of political science is often seen as a study of political movements and mechanisms; more concerned with the patterns and statistics of human activity than with the basic human elements. But, ultimately, politics is a human construction, and any human construction is shaped by the human beings who created it and participate in it. Nowhere, perhaps, is this more apparent than in the idea of scandal, of a political secret whose potential to destabilize or alter politics at large comes entirely -

The Election of 1824 I

Do Now 151, 383 Based on this chart, who became president in 1824? The Presidential Election of 1824 Henry Clay VS. William CrawfordVS. John Quincy Adams VS. Andrew Jackson Directions: 1. Google Classroom 2. Open: Election of 1824 What does the Constitution say? Amendment XII The person having the greatest number of [electoral] votes for President, shall be the President… and if no person have such majority... the House of Representatives shall choose immediately, by ballot, the President...in choosing the President, the votes shall be taken by states, the representation from each state having one vote. Is that fair? 39.3 million people 582,000 people Intro. Video What do you notice on the Electoral College Map? Type here The Election of 1824 I. Results Vs. A. No candidate won a majority of the electoral votes 1. Andrew Jackson gets most 2. John Quincy Adams get second most B. Constitutional Response 1. 12th Amendment determines what to do 2. House of Representatives will decide who becomes president ● Leader of the House of The Corrupt Bargain? Representatives ● Elected by the members of the majority party ● What they do: ○ Sets the order of issues discussed ○ Moderates debates ○ Determine who sits II. House of Representatives decides on what committee A. Henry Clay was the Speaker of the House The Corrupt Bargain? B. The Deal 1. A newspaper published an unsigned letter. 2. Letter says that John Q. Adams promised Clay would become Secretary of State if he convinced people to vote for him. The Corrupt Bargain? C. Outcome Tally sheet showing each state’s vote 1. -

Synopsis of American Political Parties

Synopsis of American Political Parties FEDERALISTS DEMOCRATIC-REPUBLICANS Favored strong central gov't emphasized states' rights Social order & stability important Stressed civil liberties & public trust "True patriots vs. the subversive rabble" "Rule of all people vs. the favored few" "Loose" constructionists "Strict" constructionists Promoted business & manufacturing Encouraged agrarian society Favored close ties with Britain Admired the French Strongest in Northeast Supported in South & West Gazette of the United States (John Fenno) National Gazette (Philip Freneau) Directed by Hamilton (+ Washington) Founded by Jefferson (+ Madison) First Two-Party System: 1780s-1801 During most of George Washington's presidency, no real two-party political system existed. The Constitution made no provision whatever for political parties. While its framers recognized that reasonable disagreement and organized debate were healthy components in a democratic society, creation of permanent factions was an extreme to be avoided. (The consensus among the founding fathers was that political parties were potentially dangerous because they divided society, became dominated by narrow special interests, and placed mere party loyalty above concern for the common welfare.) Hence, to identify Washington with the Federalist Party is an ex post facto distinction. Accordingly, Washington's first "election" is more accurately described as a "placement"; his second election was procedural only. The first presidential challenge whereby the citizenry genuinely expressed choice between candidates affiliated with two separate parties occurred in 1896, when John Adams won the honor of following in Washington's footsteps. The cartoon above shows the infamous brawl in House of Representatives between Democratic-Republican Matthew Lyon of Vermont and Federalist Roger Griswold from Connecticut. -

Andrew Jackson

THE JACKSONIAN ERA DEMOCRATS AND WHIGS: THE SECOND PARTY SYSTEM THE “ERA OF GOOD FEELINGS” • James Monroe (1817-1825) was the last Founder to serve as President • Federalist party had been discredited after War of 1812 • Monroe unopposed for reelection in 1820 • Foreign policy triumphs: • Adams-Onís Treaty (1819) settled boundary with Mexico & added Florida • Monroe Doctrine warned Europeans against further colonization in Americas James Monroe, By Gilbert Stuart THE ELECTION OF 1824 & THE SPLIT OF THE REPUBLICAN PARTY • “Era of Good Feelings” collapsed under weight of sectional & economic differences • New generation of politicians • Election of 1824 saw Republican party split into factions • Andrew Jackson received plurality of popular & electoral vote • House of Representatives chose John Quincy Adams to be president • Henry Clay became Secretary of State – accused of “corrupt bargain” • John Quincy Adams’ Inaugural Address called in vain for return to unity THE NATIONAL REPUBLICANS (WHIGS) • The leaders: • Henry Clay • John Quincy Adams • Daniel Webster • The followers: • Middle class Henry Clay • Educated • Evangelical • Native-born • Market-oriented John Quincy Adams WHIG ISSUES • Conscience Whigs – abolition, temperance, women’s rights, etc. • Cotton Whigs – internal improvements & protective tariffs to foster economic growth (the “American System”) THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLICANS (DEMOCRATS) • The leaders: • Martin Van Buren • Andrew Jackson • John C. Calhoun • The followers: Martin Van Buren • Northern working class & Southern planter aristocracy • Not well-educated • Confessional churches • Immigrants • Locally-oriented John C. Calhoun DEMOCRATIC ISSUES • Limited power for federal government & states’ rights • Opposition to “corrupt” alliance between government & business • Individual freedom from coercion “KING ANDREW” & THE “MONSTER BANK” • Marshall’s decision in McCulloch v. -

John Quincy Adams Influence on Washington's Farewell Address: A

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Undergraduate Research La Salle Scholar Winter 1-7-2019 John Quincy Adams Influence on ashingtW on’s Farewell Address: A Critical Examination Stephen Pierce La Salle University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/undergraduateresearch Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, International Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, Military History Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, National Security Law Commons, President/Executive Department Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pierce, Stephen, "John Quincy Adams Influence on ashingtW on’s Farewell Address: A Critical Examination" (2019). Undergraduate Research. 33. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/undergraduateresearch/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the La Salle Scholar at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. John Quincy Adams Influence on Washington’s Farewell Address: A Critical Examination By Stephen Pierce In the last official letter to President Washington as Minister to the Netherlands in 1797, John Quincy Adams expressed his deepest thanks and reverence for the appointment that was bestowed upon him by the chief executive. As Washington finished his second and final term in office, Adams stated, “I shall always consider my personal obligations to you among the strongest motives to animate my industry and invigorate my exertions in the service of my country.” After his praise to Washington, he went into his admiration of the president’s 1796 Farewell Address. -

The Age of Jackson Test Study Guide Format • 15 Multiple Choice • Short Answer - Chose 4 out 10 • Essay - Evaluate the Presidency of Andrew Jackson

The Age of Jackson Test Study Guide Format • 15 Multiple Choice • Short Answer - Chose 4 out 10 • Essay - Evaluate the Presidency of Andrew Jackson. Short Answers 1. What was unusual about the Presidential Election of 1824? How was the winner of this election decided? o Jackson had the most popular votes, but he didn’t win. Since the vote was split 4 ways (JQA, Clay, Crawford, and Jackson), he did not get required number of electoral votes. So, the House of Representatives decided the president. Henry Clay used his power to make sure JQA had enough votes to win the election. JQA was elected president. Corrupt bargain – Henry Clay was given Secretary of State because he helped JQA win. Position usually meant he would be the next president (was stepping stone). Was quid pro quo/ logrolling. 2. What political party that opposed Jackson was created durinG this era? What did they stand for? o The political party that opposed Jackson was the Whigs. They opposed Andrew Jackson, and called him “King Andrew”. Their name came from the Whig Party in England, who opposed the king. They favored Clay’s American system ( a national bank, federal funding of internal improvements, a protective tariff). It was mainly New Englanders and residents of mid-Atlantic and upper-Middle-Western states. 3. What did Jackson’s Vice-President [John C. Calhoun] say in response to Jackson’s faMous toast on the tariff issue in 1830, and what exactly does this toast mean? With whom would you have toasted, the President or Vice-President? Why? o “The Union, next to our liberty, most dear.” Union and liberty go hand in hand. -

John Quincy Adams and the Dorcas Allen Case, Washington, DC

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Fall 2010 Slavery exacts an impossible price: John Quincy Adams and the Dorcas Allen case, Washington, DC Alison T. Mann University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Mann, Alison T., "Slavery exacts an impossible price: John Quincy Adams and the Dorcas Allen case, Washington, DC" (2010). Doctoral Dissertations. 531. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/531 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SLAVERY EXACTS AN IMPOSSIBLE PRICE: JOHN QUINCY ADAMS AND THE DORCAS ALLEN CASE, WASHINGTON, D.C. BY ALISON T. MANN Bachelor of Arts, Rutgers University, 1991 Master of Arts, University of New Hampshire, 2003 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University ofNew Hampshire In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History September, 2010 UMI Number: 3430785 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3430785 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. -

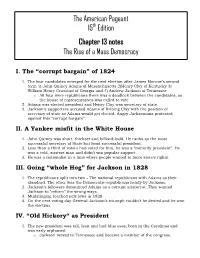

The American Pageant 15 Edition Chapter 13 Notes the Rise of A

The American Pageant th 15 Edition Chapter 13 notes The Rise of a Mass Democracy I. The “corrupt bargain” of 1824 1. The four candidates emerged for the next election after James Monroe’s second term 1) John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts 2)Henry Clay of Kentucky 3) William Henry Crawford of Georgia and 4) Andrew Jackson of Tennessee. o All four were republicans there was a deadlock between the candidates, so the house of representatives was called to vote. 2. Adams was elected president and Henry Clay was secretary of state. 3. Jackson’s supporters accused Adams of Bribing Clay with the position of secretary of state so Adams would get elected. Angry Jacksonians protested against this “corrupt bargain”. II. A Yankee misfit in the White House 1. John Quincy was short, thickset and billiard-bald. He ranks as the most successful secretary of State but least successful president. 2. Less than a third of voters had voted for him, he was a “minority president”. He was a cold, austere man and didn’t win popular support. 3. He was a nationalist in a time where people wanted to more state’s rights. III. Going “whole Hog” for Jackson in 1828 1. The republicans split into two – The national republicans with Adams as their standard. The other was the Democratic-republicans heady by Jackson. 2. Jackson’s followers denounced Adams as a corrupt aristocrat. They wanted Jackson to “reform” the wrong ways. 3. Mudslinging reached new lows in 1828. 4. On the next voting day General Jackson’s triumph couldn’t be denied and he won the election. -

The Corrupt Bargain

Insight The Corrupt Bargain MARCH 15, 2010 From The Feehery Theory In 1824, the House of Representatives awarded the Presidency to John Quincy Adams after Henry Clay, who was then the House Speaker, concluded that he wouldn’t be President and cut a deal that landed him the job of Secretary of State. It seemed like a good deal for Adams and a good deal for Clay. But to supporters of Andrew Jackson, America’s first true populist leader, this was a “corrupt bargain”, a sign of a decadent and untrustworthy political process, and a rallying cry for a new class of American voters. The “corrupt bargain” would haunt both Adams and Clay for the rest of their careers. Adams became only the second one-term President (the first was his father), losing easily to Jackson in 1828. Clay, although he would prove to be the most powerful Speaker in history, would never become President. Congressional Democrats are now embarking on their own version of the “corrupt bargain”. House Democrats have dreamed up a parliamentary device to vote on a health care bill that will become the law of the land (for how long, nobody really knows), without actually ever voting on it. They are using a parliamentary device known as the self-executing rule. This is a rule that allows debate on one piece of legislation while deeming another piece of legislation passed through the House. Pelosi herself has said that she thinks that the Senate bill is so bad that she doesn’t want to put her members through a stand-alone vote on it. -

"The Jacksonian Reformation: Political Patronage and Republican Identity"

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2019 "The Jacksonian Reformation: Political Patronage and Republican Identity" Max Matherne University of Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Matherne, Max, ""The Jacksonian Reformation: Political Patronage and Republican Identity". " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5675 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Max Matherne entitled ""The Jacksonian Reformation: Political Patronage and Republican Identity"." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. Daniel Feller, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Luke Harlow, Ernest Freeberg, Reeve Huston Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) The Jacksonian Reformation: Political Patronage and Republican Identity A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Max Matherne August 2019 Dedicated to the memory of Joshua Stephen Hodge (1984-2019), a great historian and an even better friend.