Biological Opinion on the Catalina-Rincon Firescape Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Pima County Multi-Species Conservation Plan, Arizona

United States Department of the Interior Fish and ,Vildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Office 2321 West Royal Palm Road, Suite 103 Phoenix, Arizona 85021-4951 Telephone: (602) 242-0210 Fax: (602) 242-2513 In reply refer to: AESO/SE 22410-2006-F-0459 April 13, 2016 Memorandum To: Regional Director, Fish and Wildlife Service, Albuquerque, New Mexico (ARD-ES) (Attn: Michelle Shaughnessy) Chief, Arizona Branch, Re.. gul 7/to . D'vision, Army Corps of Engineers, Phoenix, Arizona From: Acting Field Supervisor~ Subject: Biological and Conference Opinion on the Pima County Multi-Species Conservation Plan, Arizona This biological and conference opinion (BCO) responds to the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) requirement for intra-Service consultation on the proposed issuance of a section lO(a)(l)(B) incidental take permit (TE-84356A-O) to Pima County and Pima County Regional Flood Control District (both herein referenced as Pima County), pursuant to section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (U.S.C. 1531-1544), as amended (ESA), authorizing the incidental take of 44 species (4 plants, 7 mammals, 8 birds, 5 fishes, 2 amphibians, 6 reptiles, and 12 invertebrates). Along with the permit application, Pima County submitted a draft Pima County Multi-Species Conservation Plan (MSCP). On June 10, 2015, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE) requested programmatic section 7 consultation for actions under section 404 of the Clean Water Act (CW A), including two Regional General Permits and 16 Nationwide Permits, that are also covered activities in the MSCP. This is an action under section 7 of the ESA that is separate from the section 10 permit issuance to Pima Couny. -

Bear Wallow-Mt. Lemmon Area, Santa Catalina

Structural geology of the Mt. Bigelow-Bear Wallow- Mt. Lemmon area, Santa Catalina Mountains, Arizona Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic); maps Authors Waag, Charles Joseph, 1931- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 07:04:44 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565165 STRUCTURAL GEOLOGY OF THE MT. BIGELOW- BEAR WALLOW-MT. LEMMON AREA, SANTA CATALINA MOUNTAINS, ARIZONA by Charles Joseph Waag A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 8 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles J« Waag_________________________________ entitled STRUCTURAL GEOLOGY OF THE MT. BIGELOW-BEAR WALLOW- MT. LEMMON AREA, SANTA CATALINA MOUNTAINS, ARIZONA be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy______________________________ % /96r After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:* This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination. The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. -

Building Manager Alternate 2 Art Building Manager Albert Chamillard 621-95093/520-954-9654 [email protected] Dept

Bldg. No. Building Name Department Dean/Dir/dept Head/Resp Person Room # Phone Building Manager Alternate 2 Art Building Manager Albert Chamillard 621-95093/520-954-9654 [email protected] Dept. 2201 only Alternate James Kushner 621-7567/520-419-0944 [email protected] Alternate Kristen Schmidt 621-9510/520-289-3123 [email protected] Dept. 3504 School of Art only Building Manager Carrie M. Scharf Art 108 621-1464/520-488-7869 [email protected] Alternate Ginette K. Gonzalez 621-1251 [email protected] Alternate Maria Sanchez 621-7000 [email protected] Alternate Michelle Stone-Eklund 108 621-7001 [email protected] 2A Art Museum Building Manager Carrie M. Scharf 621-1464 [email protected] Alternate Michell Stone-Eklund 621-7001 [email protected] Alternate Ginette K. Gonzalez 621-1251 [email protected] 3/3A Drama Dept. 3509 School of Theatre, Film & Television Building Manager Edward Kraus 621-1104/678-457-0092 [email protected] Alternate Stacy Dugan 621-1561/520-834-2196 [email protected] Alternate Jennifer Lang 621-1277/626-321-7264 [email protected] Dept. 3504 School of Art only Building Manager Carrie M. Scharf 621-1464/520-488-7869 [email protected] Alternate Ginette K. Gonzalez 621-1251 [email protected] Alternate Maria Sanchez 621-7000 [email protected] Alternate Michelle Stone-Eklund 621-7001 [email protected] 4/4A Fred Fox School of Music Building Manager Carson Scott 621-9853/520-235-5071 [email protected] Alternate Owen Witzeman 520-272-2446 [email protected] Alternate Kiara Johnson 760-445-5458 [email protected] 5 Coconino Hall Building Manager Alex Blandeburgo Likins A104 621-4173 [email protected] Alternate Megan Mesches 621-6644 [email protected] 6 Slonaker Dept. -

Coronado National Forest Draft Land and Resource Management Plan I Contents

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Coronado National Forest Southwestern Region Draft Land and Resource MB-R3-05-7 October 2013 Management Plan Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona, and Hidalgo County, New Mexico The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Front cover photos (clockwise from upper left): Meadow Valley in the Huachuca Ecosystem Management Area; saguaros in the Galiuro Mountains; deer herd; aspen on Mt. Lemmon; Riggs Lake; Dragoon Mountains; Santa Rita Mountains “sky island”; San Rafael grasslands; historic building in Cave Creek Canyon; golden columbine flowers; and camping at Rose Canyon Campground. Printed on recycled paper • October 2013 Draft Land and Resource Management Plan Coronado National Forest Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona Hidalgo County, New Mexico Responsible Official: Regional Forester Southwestern Region 333 Broadway Boulevard, SE Albuquerque, NM 87102 (505) 842-3292 For Information Contact: Forest Planner Coronado National Forest 300 West Congress, FB 42 Tucson, AZ 85701 (520) 388-8300 TTY 711 [email protected] Contents Chapter 1. -

A GUIDE to the GEOLOGY of the Santa Catalina Mountains, Arizona: the Geology and Life Zones of a Madrean Sky Island

A GUIDE TO THE GEOLOGY OF THE SANTA CATALINA MOUNTAINS, ARIZONA: THE GEOLOGY AND LIFE ZONES OF A MADREAN SKY ISLAND ARIZONA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 22 JOHN V. BEZY Inside front cover. Sabino Canyon, 30 December 2010. (Megan McCormick, flickr.com (CC BY 2.0). A Guide to the Geology of the Santa Catalina Mountains, Arizona: The Geology and Life Zones of a Madrean Sky Island John V. Bezy Arizona Geological Survey Down-to-Earth 22 Copyright©2016, Arizona Geological Survey All rights reserved Book design: M. Conway & S. Mar Photos: Dr. Larry Fellows, Dr. Anthony Lux and Dr. John Bezy unless otherwise noted Printed in the United States of America Permission is granted for individuals to make single copies for their personal use in research, study or teaching, and to use short quotes, figures, or tables, from this publication for publication in scientific books and journals, provided that the source of the information is appropriately cited. This consent does not extend to other kinds of copying for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, for creating new or collective works, or for resale. The reproduction of multiple copies and the use of articles or extracts for comer- cial purposes require specific permission from the Arizona Geological Survey. Published by the Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress, #100, Tucson, AZ 85701 www.azgs.az.gov Cover photo: Pinnacles at Catalina State Park, Courtesy of Dr. Anthony Lux ISBN 978-0-9854798-2-4 Citation: Bezy, J.V., 2016, A Guide to the Geology of the Santa Catalina Mountains, Arizona: The Geology and Life Zones of a Madrean Sky Island. -

Social and Economic Sustainability Report

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southwestern Region Coronado National Forest November 2008 Social and Economic Sustainability Report Coronado NF Social and Economic Sustainability Report Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................1 Historical Context........................................................................................................................................4 Demographic and Economic Conditions ...................................................................................................6 Demographic Patterns and Trends.............................................................................................................6 Total Persons.........................................................................................................................................7 Population Age......................................................................................................................................7 Racial / Ethnic Composition..................................................................................................................8 Educational Attainment.......................................................................................................................10 Housing ...............................................................................................................................................12 -

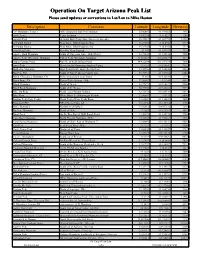

Peak List Please Send Updates Or Corrections to Lat/Lon to Mike Heaton

Operation On Target Arizona Peak List Please send updates or corrections to Lat/Lon to Mike Heaton Description Comment Latitude Longitude Elevation "A" Mountain (Tempe) ASU campus by Sun Devil Stadium 33.42801 -111.93565 1495 AAA Temp Temp Location 33.42234 -111.8227 1244 Agassiz Peak @ Snow Bowl Tram Stop (No access to peak) 35.32587 -111.67795 12353 Al Fulton Point 1 Near where SR260 tops the Rim 34.29558 -110.8956 7513 Al Fulton Point 2 Near where SR260 tops the rim 34.29558 -110.8956 7513 Alta Mesa Peak For Alta Mesa Sign-up 33.905 -111.40933 7128 Apache Maid Mountain South of Stoneman Lake - Hike/Drive? 34.72588 -111.55128 7305 Apache Peak, Whetstone Mountain Tallest Peak, Whetstone Mountain 31.824583 -110.429517 7711 Aspen Canyon Point Rim W. of Kehl Springs Point 34.422204 -111.337874 7600 Aztec Peak Sierra Ancha Mountains South of Young 33.8123 -110.90541 7692 Battleship Mountain High Point visible above the Flat Iron 33.43936 -111.44836 5024 Big Pine Flat South of Four Peaks on County Line 33.74931 -111.37304 6040 Black (Chocolate) Mountain, CA Drive up and park, near Yuma 33.055 -114.82833 2119 Black Butte, CA East of Palm Springs - Hike 33.56167 -115.345 4458 Black Mountain North of Oracle 32.77899 -110.96319 5586 Black Rock Mountain South of St. George 36.77305 -113.80802 7373 Blue Jay Ridge North end of Mount Graham 32.75872 -110.03344 8033 Blue Vista White Mtns. S. of Hannagan Medow 33.56667 -109.35 8000 Browns Peak (Four Peaks) North Peak of Four Peaks Range 33.68567 -111.32633 7650 Brunckow Hill NE of Sierra Vista, AZ 31.61736 -110.15788 4470 Bryce Mountain Northwest of Safford 33.02012 -109.67232 7298 Buckeye Mountain North of Globe 33.4262 -110.75763 4693 Burnt Point On the Rim East of Milk Ranch Point 34.40895 -111.20478 7758 Camelback Mountain North Phoenix Mountain - Hike 33.51463 -111.96164 2703 Carol Spring Mountain North of Globe East of Highway 77 33.66064 -110.56151 6629 Carr Peak S. -

Subject: Safety Programs and Requirements: Mountain Travel and Habitat Section

Subject: Safety Programs and Requirements: Mountain Travel and Habitat Section: V Date: 08/02/2011 (rev. 1) Page 1 of 3 Environment, Health, & Safety Manual Mountain Travel and Habitat Steward Observatory operates telescopes, labs, shops and other facilities on several mountains in Southern Arizona. Each of these sites have the potential for hazardous weather conditions year around including heavy rain, flash floods, very high winds, and ice and snow particularly in the winter months. In its effort to minimize risk to employees and visitors who must travel in the mountain areas, the Steward Observatory has established the following policies and procedures: 1. Employees and visitors are encouraged to either stay on the mountain for the night if they must work late, or leave the mountain in time to arrive at the bottom by sunset. If emergency situations require travel after dark, they are required to carry a two-way radio and make arrangements with another employee on the mountain to monitor the radio channel until the traveling person reaches the bottom/top of the mountain. When the traveling person arrives at their destination, they must announce their arrival to the monitor at the other end. 2. Each observatory department that has vehicles which are primarily used to travel to/from mountain sites, will outfit those vehicles with proper supplies that can be used in the event of an accident or breakdown on mountain roads. The supplies should be kept in a duffel bag and will include at least the following: Listing of all emergency telephone -

Roberto Furfaro(2), Eric Christensen(1), Rob Seaman(1), Frank Shelly(1)

SYNERGISTIC NEO-DEBRIS ACTIVITIES AT UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA Vishnu Reddy(1), Roberto Furfaro(2), Eric Christensen(1), Rob Seaman(1), Frank Shelly(1) (1) Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA, Email:[email protected]. (2) Department of Systems and Industrial Engineering, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA. ABSTRACT and its neighbour, the 61-inch Kuiper telescope (V06) for deep follow-up. Our survey telescopes rely on 111 The University of Arizona (UoA) is a world leader in megapixel 10K cameras that give G96 a 5 square-degree the detection and characterization of near-Earth objects and 703 a 19 square-degree field of view. (NEOs). More than half of all known NEOs have been Catalina Sky Survey has been a dominant contributor to discovered by two surveys (Catalina Sky Survey or CSS the discovery of near Earth asteroids and comets over its and Spacewatch) based at UoA. All three known Earth more than two decades of operation. In 2018, CSS was impactors (2008 TC3, 2014 AA and 2018 LA) were the first NEO survey to discover >1000 new NEOs in a discovered by the Catalina Sky Survey prior to impact single year, including five larger than one kilometre, enabling scientists to recover samples for two of them. and more than 200 > 140 metres. Capitalizing on our nearly half century of leadership in NEO discovery and characterization, UoA has Our survey was a major contributor satisfying the embarked on a comprehensive space situational international Spaceguard Goal (1992) [4] of finding awareness program to resolve the debris problem in cis- 90% of the NEAs larger than 1-km in diameter, and has lunar space. -

Feasibility Study for the SANTA CRUZ VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA

Feasibility Study for the SANTA CRUZ VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA FINAL Prepared by the Center for Desert Archaeology April 2005 CREDITS Assembled and edited by: Jonathan Mabry, Center for Desert Archaeology Contributions by (in alphabetical order): Linnea Caproni, Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona William Doelle, Center for Desert Archaeology Anne Goldberg, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona Andrew Gorski, Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona Kendall Kroesen, Tucson Audubon Society Larry Marshall, Environmental Education Exchange Linda Mayro, Pima County Cultural Resources Office Bill Robinson, Center for Desert Archaeology Carl Russell, CBV Group J. Homer Thiel, Desert Archaeology, Inc. Photographs contributed by: Adriel Heisey Bob Sharp Gordon Simmons Tucson Citizen Newspaper Tumacácori National Historical Park Maps created by: Catherine Gilman, Desert Archaeology, Inc. Brett Hill, Center for Desert Archaeology James Holmlund, Western Mapping Company Resource information provided by: Arizona Game and Fish Department Center for Desert Archaeology Metropolitan Tucson Convention and Visitors Bureau Pima County Staff Pimería Alta Historical Society Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona Sky Island Alliance Sonoran Desert Network The Arizona Nature Conservancy Tucson Audubon Society Water Resources Research Center, University of Arizona PREFACE The proposed Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area is a big land filled with small details. One’s first impression may be of size and distance—broad valleys rimmed by mountain ranges, with a huge sky arching over all. However, a closer look reveals that, beneath the broad brush strokes, this is a land of astonishing variety. For example, it is comprised of several kinds of desert, year-round flowing streams, and sky island mountain ranges. -

SUMMER HIKING GUIDE Arizona Is a Dream State for Hikers

SUMMER HIKING GUIDE Arizona is a dream state for hikers. There’s a trail for everyone, and the weather allows for year-round hiking. Summer, however, is when most people hit the trail. Thus, our fifth-annual Summer Hiking Guide, which spotlights our top 10 trails, along with some bonus hikes in the White Mountains and five wheelchair-accessible trails that are just right this time of year. BY ROBERT STIEVE One of the most popular trails in the Coconino National Forest, the West Fork Oak Creek Trail requires several creek-crossings. | PAUL MARKOW 18 JUNE 2012 for the trailhead. SPECIAL CONSIDERATION: National Park Widforss Trail Service fees apply. NORTH RIM, GRAND CANYON 1 VEHICLE REQUIREMENTS: None 1 Inner Basin Trail Widforss Trail DOGS ALLOWED: No FLAGSTAFF NORTH RIM, GRAnd CANYON USGS MAP: Bright Angel Point Named for Gunnar Widforss, an artist who INFORMATION: Backcountry Office, Grand Humphreys Trail FLAGSTAFF 6 painted landscapes in the national parks in the Canyon National Park, 928-638-7875 or www. 4 Weatherford Trail 1920s and 1930s, this relatively easy trail fol- nps.gov/grca 3 FLAGSTAFF lows the rim of the Grand Canyon to Widforss FLAGSTAFF Point. And getting there, you’ll pass through Foot Note: At the height of Gunnar Widforss’ West Fork Oak 5 Creek Trail an idyllic forest of Colorado blue spruce, career in 1929, just after his 50th birthday, the OAK CREEK CANYON 8 Engelmann spruce, white firs, Douglas firs and American stock market crashed, sending the 9 Maxwell Trail MOGOLLON RIM aspens, the latter of which can be seen growing artist into near obscurity and his paintings into 7 West Clear Creek Trail in droves where recent fires have burned. -

Coronado National Forest Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report

United States Department of Agriculture Coronado National Forest Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report Forest Service Southwestern Region Coronado National Forest July 2017 Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S.