Cosmopolitan Dreams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Karachi MS/ BS/ Master’S / Diploma / Certificate Programs

University of Karachi MS/ BS/ Master’s / Diploma / Certificate Programs Admissions 2019-20 Our Vision To become a world recognized university accessible to all sections of society and a representative of the best of human values and intellectual endeavor in all academic disciplines, contributing to the success and prosperity of the nation Our Mission The University aims to be a prominent international seat of higher learning, providing a vibrant academic environment and a focal point for creativity through research, mobilization of the community and quality education for humanity. University of Karachi Prof. Dr. Khalid M. Iraqi Vice Chancellor MESSAGE I welcome all the keen seekers of admission to the University of Karachi, who can secure admission in the desired department by satisfying the specific criteria. I find it important to highlight that the University of Karachi is making efforts to promote higher education in the region. Due to this fact, University of Karachi stands in the list of top 200 Universities in Asia. Nevertheless, this journey of rapid development does not limit itself to the current international ranking Only; we are rather trying hard to take our Alma Mater to the list of top universities in the world. In this relation, extensive developmental work is being carried out in every sphere of the University, be it academic or administrative. Our teaching and research is on a par with the international standards and address issues that have a global impact. The facilities University provides make the learning process easier and interesting. In short, we are fervently trying to rise a well-educated, professionally skilled and technically advanced new generation in Pakistan. -

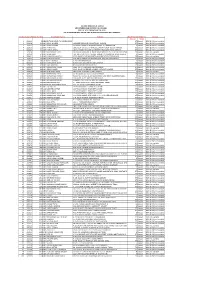

List of Share Holders

GATRON (INDUSTRIES) LIMITED 2ND INTERIM CASH DIVIDEND NO. 32 (20%) FOR THE YEAR ENDING JUNE 30, 2019 LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS WHOSE CNIC & IBAN NOT AVAILABLE WITH COMPANY Sr. No Warrant # Folio Number Shareholder Name Address Net Dividend Dividend Reason Amount Status 1 320022 91 SHARES TO BE ISSUED TO SHAREHOLDER 675 Unpaid IBAN & CNIC not available 2 320024 233 MR. ABDUL WAHEED AL ZAHEER DRRALINE KALAKOTLYARI, KARACHI. 675 Unpaid IBAN & CNIC not available 3 320025 294 MR. IMDAD HUSSAIN 112 AMIR KHUSRO ROAD,BAHADURABAD BL 7/8KARACHI -8 67 Unpaid IBAN & CNIC not available 4 320026 313 MRS. MARIE HOU CONSTELLATION 5/1, CH KHALIQUZ ZAMAN ROAD4-B GIZRI, KARACHI. 800 Unpaid IBAN & CNIC not available 5 320027 331 MRS. AMINA SHAKIL 100-AL-HAMRA HOUSING SOCIETYOFF TIPO SULTAN ROAD,KARACHI. 675 Unpaid IBAN & CNIC not available 6 320028 423 MR. MOHAMMAD HANIF C/O ANWAR MOOSANI AL NOOR SUGAR MILLSLTD 96 A S.M.C.H. SOCIETYKARACHI -3. 148 Unpaid IBAN not available 7 320030 516 MR. JAVED IQBAL FLAT NO.2, PLOT NO. 4C, SUNSET LANE NO.4COMMERCIAL AREA, DEFENCE SOCIETY, KAR6A7CUHnI paid IBAN & CNIC not available 8 320031 543 MRS. NARGIS SHAUKAT ALI 327/2 GARDEN EAST OFF BRITTO ROADSOLDIER BAZZARKARACHI 797 Unpaid IBAN not available 9 320032 552 MRS. RUKAYA KASBATI FLAT NO MI EMPIRE SQUAREJAMALIDIN AFGHANI ROADKARACHI 405 Unpaid IBAN & CNIC not available 10 320033 585 CH. ABDUL RAZAQUE D 269 K D A (1A)KARACHI 67 Unpaid IBAN & CNIC not available 11 320034 620 MR. MUHAMMAD ALTAF B 132 BLOCK 15GULSHAN E IQBALKARACHI 742 Unpaid IBAN & CNIC not available 12 320035 625 MR. -

Prospectus Evening Program University of Karachi

2014 PROSPECTUS EVENING PROGRAM UNIVERSITY OF KARACHI Admissions - 2014 Contents Message from the Vice Chancellor i Faculty of Pharmacy Message from the Director Evening Program ii Pharmacogonosy 27 University Officials iii Pharmacology 28 Admission Schedule iv Pharmaceutical Chemistry 29 Pharmaceutice 30 Introduction The Journey Begins Here 1 Faculty of Science The Karachi University Degree 2 Agriculture & Agribusiness Evening Program 3 Management 31 Applied Chemistry & General Information 4 Chemical Technology 32 System of Studies 5 Applied Physics 33 Instructions for Foreign Students 5 Biochemistry 34 Admission Policy 6 Biotechnology 35 Admission Form 8 Botany 36 Chemistry 37 Faculty of Arts / Education Computer Science 38 Arabic 9 Environmental Studies 39 Economics 10 Food Science & Technology 40 Education 11 Mathematical Sciences 41 English 12 Microbiology 42 General History 13 Petroleum Technology 43 International Relations 14 Physics 44 Library and Inf. Sciences 15 Physiology 45 Mass Communication 16 Statistics 46 Persian 17 Zoology 47 Psychology 18 Sociology 19 Table - I (Masters Programs) 48 Social Work 20 Table - II (Bachelor Programs) 49 Special Education 21 Table - III (Diploma Program) 55 Urdu 22 Table - IV (Certificate Programs) 54 Women’ Studies 23 Procedure of Admission for Selected Candidates 57 Faculty of Management and Table - V (Fee Structure) 59 Administrative Sciences Table - VI (Last year closing 61 percentages) Commerce 24 Karachi University Business School 25 Academic Calendar 63 Public Administration 26 University of Karachi Prof. Dr. Muhammad Qaiser ViceViceVice-Vice ---ChancellorChancellor MESSAGE I welcome all the keen seekers of admission to the University of Karachi, who can secure admission in the desired department by satisfying the specific criteria. -

Hasan Manzar: an Introduction

Hasan Manzar: An Introduction B , Syed Manzar Hasan, who writes under the pen name of Hasan Manzar, comes of a north Indian middle class family. His great-grandfather carried a price on his head for his involvement in the War of Independence—otherwise referred to as the Great Mutiny—against the English. Luckily, he was never caught and escaped imperial wrath. Hasan Manzar was born in Hapur (Uttar Pradesh) on March . His family migrated to Pakistan in and settled in Lahore where he received most of his formal education. He attended Forman Christian College, Islamia College, and, later, King Edward Medical College for his medical degree. He did his postgraduate work in psychiatry at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. He lives in Hyderabad, Sindh, where he heads a psychiatric clinic. He is married and has three children. His son and elder daughter are medical doctors, and his younger daughter is a university student. His wife is a pediatrician by profession. To date he has published four books: three collections of short stories, viz., Rih≥’µ (Emancipation; ), Nadµdµ (Greedy; ), and Ins≥n k≥ D®sh (Man’s Country; ); and a translation into Urdu of Premchand’s last, unfinished Hindi novel Mangal Sutar (). A book of children’s stories and a fourth collection of short stories await publication. In his conception of the form and technique of the short story, Hasan Manzar is very much a realist, inclining towards a traditional, old- fashioned view of plot, character and narrative in his story-telling. But his realism is so subtle, his stories so true to life, that while reading him, one often forgets to notice that a story is being told. -

List of Shareholders Withheld Final Cash Dividend 2019

GATRON (INDUSTRIES) LIMITED FINAL CASH DIVIDEND NO.33 (150%) FOR THE YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2019 LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS WHOSE CNIC & IBAN NOT AVAILABLE WITH COMPANY Sr. No. Warrant # Folio Number Shareholder Name Net Dividend Amount Dividend Status Reason 1 330022 91 SHARES TO BE ISSUED TO SHAREHOLDER 5250 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 2 330024 233 MR. ABDUL WAHEED 5250 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 3 330025 294 MR. IMDAD HUSSAIN 525 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 4 330026 313 MRS. MARIE HOU 5250 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 5 330027 331 MRS. AMINA SHAKIL 5250 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 6 330028 423 MR. MOHAMMAD HANIF 1155 Unpaid IBAN not Available 7 330030 516 MR. JAVED IQBAL 525 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 8 330031 543 MRS. NARGIS SHAUKAT ALI 7012 Unpaid IBAN not Available 9 330032 552 MRS. RUKAYA KASBATI 3150 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 10 330033 585 CH. ABDUL RAZAQUE 525 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 11 330034 620 MR. MUHAMMAD ALTAF 5775 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 12 330035 625 MR. JAMIL HAROON 1050 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 13 330036 629 MR. MOHAMMAD NAWAZ 5250 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 14 330037 696 MR. IRSHAD AHMED 5250 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 15 330038 705 MRS. RUKHSANA JAFAR 525 Unpaid IBAN not Available 16 330039 739 MR. MOHAMMAD RAFIQ 5775 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 17 330040 831 MR. MUHAMMAD FAHEEM 525 Unpaid CNIC and IBAN not Available 18 330041 873 MR. -

CBCS- M.A. Urdu,Revised Syllabus.Pdf

DEPARTMENT OF URDU University Of Delhi Delhi - 110007 PROGRAMME BROCHURE MASTER OF ARTS (Effective from Academic Year 2018-19) M. A. Urdu Revised Syllabus as approved by Academic Council on XXXX, 2018 and Executive Council on YYYY, 2018 Department of Urdu, University of Delhi CONTENTS Page I. About the Department 03 II. Introduction to CBCS 03 Scope 03 Definitions 03 Programme Objectives (POs) 04 Programme Specific Outcomes (PSOs) 04 III. M. A. in Urdu Programme Details 04 Programme Structure 04 Eligibility for Admissions 10 Assessment of Students’ Performance and Scheme 10 of ExaminationPass Percentage & Promotion Criteria: Semester to Semester Progression 10 Conversion of Marks into Grades 11 Grade Points 11 CGPA Calculation 11 Division of Degree into Classes 11 Attendance Requirement 11 Span Period 11 SCHEME OF EXAMINATIONS 12 IV. Course Wise Content Details for M A Urdu Literature Programme 13 2 Department of Urdu, University of Delhi I. About the Department: Name of the Department: Department of Urdu The Department of Urdu was established in 1959. It is a big department which assumed a character in itself over the period. Apart from the MA, MPhil, and PhD courses, the Department offers Post-MA Diploma in Translation & Mass Media, and a Post-MA Diploma Course in Paleography. It also offers 3 courses in Certificate, Diploma and Advanced Diploma in Urdu language for non-Urdu knowing Students and Foreigners catering to the needs for several hundred students. As part of the research program, considerable numbers of research theses have been published and praised by critics and scholars for their quality research. -

American Telugu Association Convention in Chicago

www.Asia Times.US NRI Global Edition Email: [email protected] July 2016 Vol 7, Issue 7 American Telugu Association Convention in Chicago ATA Board: Iftekhar Shareef, ATA president Sudhaker Perikari along with Executive board and different committee chairs and co-chair . July 2016 www.Asia Times . US PAGE 2 To all the Readers and Sponsors of www.Asia Times US July 2016 www.Asia Times . US PAGE 3 Asia Times US Mohammed Noor Rahman ISSN 2159-9645 Sheikh new consul general in Editor-in-Chief Vacant Jeddah Publisher JEDDAH: Mohammed Noor Rahman Sheikh assumed charge as Azeem A. Quadeer, P.E. India’s next consul general in Jeddah EditorAsiaTimes He was given a sendoff by his colleagues in New York where he was @gmail.com first secretary at India’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations. “I am happy to be back in Jeddah,” he told Arab News. “I am Finance and Marketing looking forward to serving the Indian community and the Indian Chief pilgrims.” Madam Sheela Sheikh’s predecessor B.S. Mubarak has returned to New Delhi. MadamSheela1@gmail. Sheikh served previously in Jeddah as deputy consul general and com Haj consul before moving to New York. He has returned to a city with which he is familiar and in which he is comfortable. Chairman Just as his predecessor, Sheikh is down-to-earth and enjoys good Board of Directors rapport with the large Indian community in and around Jeddah. Vacant A native of Imphal in Manipur, Sheikh is a product of the famed Indian Foreign Service (2004 batch). -

UBL Holds the 5Th UBL Literary Excellence Awards in Karachi

PRESS RELEASE UBL holds the 5th UBL Literary Excellence Awards in Karachi Mr. Wajahat Husain, President & CEO UBL presenting the award for the Best Children’s Literature in English to Ms. Hamida Khuhro at the 5th UBL Literary Excellence Awards 2015 Karachi, 7 February, 2016: The 5th UBL Literary Excellence Awards 2015 were held at the Beach Luxury Hotel in Karachi on Sunday, 7 February 2016. The awards were held in conjunction with the 7th Karachi Literature Festival. Celebrating the literary efforts of Pakistani writers, UBL Literary Excellence Awards were held for the fifth year running. Over 123 entries were received as nominations for the seven categories of the awards. The books, which were written by Pakistani authors and published in Pakistan in the previous year, were shortlisted by an esteemed panel of judges which included the likes of (late) Mr. Intizar Hussain, Dr. Asghar Nadeem Syed, Dr. Asif Farrukhi Mr. Ghazi Salahuddin, Dr. Arfa Syeda, Ms. Kishwar Naheed, Dr. Anwaar Ahmad and Dr. Framji Minwalla. The winners from each category are: Urdu Fiction: Na-Tamaam by Muhammad Asim Butt Urdu Non-Fiction: Bazm-e-Ronaq-e-Jahan by Aslam Farrukhi Urdu Poetry: Dhoop Kiran by Imdad Hussaini Urdu Translation: Surkh Mera Naam (Urdu Translation) by Huma Anwar Children’s Urdu Literature: Sunehri Kahaniyan by Najma Parveen and Dragon Ki Wapsi by Akhtar Abbas. English Non-Fiction: The Emergence of Socialist Thought Among North Indian Muslims by Khizar Humayun Ansari Children’s English Literature: A Children’s History of Balochistan by Hamida Khuhro. Mr. Wajahat Husain, President & CEO UBL, during his speech, said that UBL has a strong connection with literature and plays an active role in promoting literary activities in Pakistan. -

School-Library-Catalogue-2021.Pdf

Contacts This catalogue lists educational books which have been published, reprinted, or imported and made available at reduced, rupee prices by Oxford University Press (OUP), Pakistan. Orders can be placed with a local bookseller. However, in case of any difficulty in obtaining your requirements, do not hesitate to get in touch with us. KaracHi QUetta faisaLabad Head Office/disTributiOn cenTre: booksHOP: Office/booksHOP: no. 38, sector 15, no. 2-11/6a, near Mannan chowk, Palm breeze Tower, near Jamiya Masjid, Korangi industrial area, M. a. Jinnah road, Quetta. Kohinoor city, faisalabad. Karachi-74900, Pakistan. Tel.: 2839044. Tel.: 8736112-15. fax: 92-41-2620126. UAN: 111 693673 (111 OXfORD). email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Tel.: 35071580-86. contact: contact: fax: 92-21-35055071-72. imran Latif adnan nasir email: [email protected] Multan disTribUTiOn cenTre: 21-P, Malik Plaza, Main Kotwali road, raheela fahim baqai, Office/booksHOP: Marketingd irector Outside aminpur bazar, faisalabad. 31-b, Gulgasht colony, Tel.: 2620124-28. fax: 92-41-2620126. salma adil, Opposite Gole bagh, sales director, south near national bank of Pakistan, Multan. email: [email protected] imran Zahoor, Tel.: 6511971. fax: 92-61-6511972. contact: Manager customer services email: [email protected] Muhammad Wasim contacts: BooksHOP: Muhammad naeem ayubi isLaMabad LG-11, Ground floor, Park Towers, regional sales Manager Office/booksHOP: shahrah e firdousi, clifton, Karachi. disTribUTiOn cenTre: 7, shalimar Plaza, Jinnah avenue, Tel.: 35376796-99. 32-b, Gulgasht colony, 99 West, blue area, islamabad-44000. contact: Tel.: (Office): 2347264-65. Opposite Gole bagh, roshan Zameer Tel.: (bookshop): 8317022-23. -

Witnessing Partition

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 21:06 09 May 2016 Witnessing Partition Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 21:06 09 May 2016 This page intentionally left blank Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 21:06 09 May 2016 Witnessing Partition Memory, History, Fiction TARUN K. SAINT Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 21:06 09 May 2016 Memory, LONDONLONDONLONDON LONDON NEW YORK NEW DELHI First published 2010 by Routledge 912 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Transferred to Digital Printing 2010 © 2010 Tarun K. Saint Typeset by Star Compugraphics Private Limited D–156, Second Floor Sector 7, Noida 201 301 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 21:06 09 May 2016 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-415-56443-4 Contents Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 Negotiating the Effects of Historical Trauma: Novels of the 1940s and 50s 61 Partition’s Afterlife: Perspectives from the 1960s and 70s 115 Narrativising the ‘Time of Partition’: Writings -

Gatron (Industries) Limited Interim Cash Dividend No.31 (95%) for the Year Ending June 30, 2019 List of Shareholders Whose Cnic & Iban Not Available with Company

GATRON (INDUSTRIES) LIMITED INTERIM CASH DIVIDEND NO.31 (95%) FOR THE YEAR ENDING JUNE 30, 2019 LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS WHOSE CNIC & IBAN NOT AVAILABLE WITH COMPANY Net Dividend Sr. No Warrant # Folio Number Shareholder Name Address Dividend Status Reason Amount 1 310021 34 NATIONAL BANK OF PAKISTAN HEAD OFFICE I.I. CHUNDRIGAR ROAD KARACHI. 5700 Paid 2 310022 91 SHARES TO BE ISSUED TO SHAREHOLDER 3800 Unpaid IBAN & CNIC not available 3 310023 145 MR. ABDUL HAFEEZ KHOKHAR D-3, WAJID SQUARE FL-7 & 8, GULSHAN-E-IQBAL, BLOCK - 16, KARACHI-47. 4441 Paid 4 310024 233 MR. ABDUL WAHEED AL ZAHEER DRRALINE KALAKOT LYARI, KARACHI. 3800 Unpaid IBAN & CNIC not available 5 310025 294 MR. IMDAD HUSSAIN 112 AMIR KHUSRO ROAD, BAHADURABAD BL 7/8 KARACHI-8 380 Unpaid IBAN & CNIC not available 6 310026 313 MRS. MARIE HOU CONSTELLATION 5/1, CH KHALIQUZ ZAMAN ROAD 4-B GIZRI, KARACHI. 3800 Unpaid IBAN & CNIC not available 7 310027 331 MRS. AMINA SHAKIL 100-AL-HAMRA HOUSING SOCIETY OFF TIPO SULTAN ROAD, KARACHI. 3800 Unpaid IBAN & CNIC not available 8 310028 423 MR. MOHAMMAD HANIF C/O ANWAR MOOSANI AL NOOR SUGAR MILLS LTD 96 A S.M.C.H. SOCIETY KARACHI-3. 836 Unpaid IBAN not available 9 310029 454 MR. NIZAM ALI GHAURI E-232 KOSAR TOWN MALIR KARACHI-37. 3800 Paid 10 310030 516 MR. JAVED IQBAL FLAT NO.2, PLOT NO. 4C, SUNSET LANE NO.4 COMMERCIAL AREA, DEFENCE SOCIETY, POST OFFICE DEFENCE SOCIETY, K3A8R0ACHI-755U0n0p.a i d IBAN & CNIC not available 11 310031 543 MRS. -

University of Delhi Syllabus M.A. Urdu

University Of Delhi Syllabus M.A. Urdu Each paper of M.A. will carry 100 marks. Distribution of marks: Home Examination 10 marks Assignment 10 marks Semester Examination 75 marks (text 30 marks, critical questions 45 marks) Attendance 05 marks SEMESTER-I Course-1: Core Course: (Basic Text) Books Prescribed: 1. Sab-Ras : Mulla Wajhi (first half) 2. Kulliyat-e-Quli Qutub Shah (first 25 Ghazals and Poems on Barkha-rut) 3. Diwan-e-Wali (Radif Alif) 4. Intikhab-e-Kalam-e-Meer: ed. Maulvi Abdul Haq (Radif Alif) 5. Intikhab-e-Sauda (first 25 Ghazals): ed. Maktaba Jamia 6. Nau Tarz-e-Murassa: Mir Mohd. Husain Ata Khan Tahseen Books Recommended: 1 Tarikh-e-Adab-e-Urdu (Vol. I) : Jameel Jalbi 2 Decan Mein Urdu : Naseeruddin Hashmi 3 Sab-Ras Ka Tanqidi Jaeza : Manzar Azmi 4 Neqd-e-Meer : Syed Abdullah 5 Mutala-e-Sauda : Mohammad Hasan 6 Urdu Ki Nasri Dastanen : Gyan Chand Jain 7 Wali Dakani : Sharib Rudaulvi Course-2 Option (i): Literary History of Urdu upto 1857 1. Urdu ka aaghaz-o-irtaqa 2. Behmani daur mein Urdu adab 3. Qutub Shahi daur mein Urdu adab 4. Adilshahi daur mein Urdu adab 5. Shumali Hind mein rekhta goi ka Aghaz aur Wali ke asraat – Khan Arzoo, Abroo, Shakir Naaji, Mazmoon, Mirza Mazhar Jan-e-Janan, Shah Hatim 6. Eiham Goi – tahzibi aur adabi moharrikat 7. Meer-o-Mirza ka ahad – Dard, Sauda, Meer Hasan, Meer 8. Dabistan-e-Delhi ke aham rujhanaat 9. Atharahveen sadi mein Urdu nasr – Karbal Katha, Quran-e-Pak ke tarjume, Nau Tarz-e-Murassa, Qissa-e- Mehr Afroz-o-Dilbar, Ajaib-ul Qasas, Fort-William College Aur Dilli College ki adabi khidmaat 10.