Memory | July 2020 1 Ó

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Ago on Another World, Red and Blue Warriors Fought Continuously, Caught in a Stalemate. for the Sake of Settling Their Disp

Long ago on another world, Red and Blue warriors fought continuously, caught in a stalemate. For the sake of settling their dispute, a neutral party named the Moderators intervened in the conflict to minimise the casualties and collateral. They decided to have select champions fight instead. These champions would be imbued with power, and set against each other. The winner of those champions would be the winner of the war. Additionally, to make sure it was fair and neutral, these champions would be selected from another unrelated race. They chose humanity. Now these Kämpfer’s clash in the shadows, unknown to the rest of humanity. In a few short days Natsuru, a normal boy who attends a school physically split in half according to gender, will find himself transformed into a Kämpfer. He is rightly shocked, as unfortunately for him Kämpfers are female. Luckily he is able to transform back, which lasts up until the next day when a gun held by another Kämpfer is rather rudely put against his head. And so the story begins. Have 1000CP to spend on the options below. Origins: You can choose your gender for free. Roll 1d3+15 for your age. Student You will be starting off this jump as an ordinary student. There is little innately special about you, beyond the norm. You have a roof over your head, 3 meals a day, and a family that may or may not be still living in the same house as you. All in all, you are perfectly set to have a relaxing decade if you wished. -

Edition 2019

YEAR-END EDITION 2019 Global Headquarters Republic Records 1755 Broadway, New York City 10019 © 2019 Mediabase 1 REPUBLIC #1 FOR 6TH STRAIGHT YEAR UMG SCORES TOP 3 -- AS INTERSCOPE, CAPITOL CLAIM #2 AND #3 SPOTS For the sixth consecutive year, REPUBLIC is the #1 label for Mediabase chart share. • The 2019 chart year is based on the time period from November 11, 2018 through November 9, 2019. • All spins are tallied for the full 52 weeks and then converted into percentages for the chart share. • The final chart share includes all applicable label split-credit as submitted to Mediabase during the year. • For artists, if a song had split-credit, each artist featured was given the same percentage for the artist category that was assigned to the label share. REPUBLIC’S total chart share was 19.2% -- up from 16.3% last year. Their Top 40 chart share of 28.0% was a notable gain over the 22.1% they had in 2018. REPUBLIC took the #1 spot at Rhythmic with 20.8%. They were also the leader at Hot AC; where a fourth quarter surge landed them at #1 with 20.0%, that was up from a second place 14.0% finish in 2018. Other highlights for REPUBLIC in 2019: • The label’s total spin counts for the year across all formats came in at 8.38 million, an increase of 20.2% over 2018. • This marks the label’s second highest spin total in its history. • REPUBLIC had several artist accomplishments, scoring three of the top four at Top 40 with Ariana Grande (#1), Post Malone (#2), and the Jonas Brothers (#4). -

Nightmare Magazine, Issue 77 (February 2019)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 77, February 2019 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial: February 2019 FICTION Quiet the Dead Micah Dean Hicks We Are All Monsters Here Kelley Armstrong 58 Rules to Ensure Your Husband Loves You Forever Rafeeat Aliyu The Glottal Stop Nick Mamatas BOOK EXCERPTS Collision: Stories J.S. Breukelaar NONFICTION The H Word: How The Witch and Get Out Helped Usher in the New Wave of Elevated Horror Richard Thomas Roundtable Interview with Women in Horror Lisa Morton AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS Micah Dean Hicks Rafeeat Aliyu MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks Support Us on Patreon or Drip, or How to Become a Dragonrider or Space Wizard About the Nightmare Team Also Edited by John Joseph Adams © 2019 Nightmare Magazine Cover by Grandfailure / Fotolia www.nightmare-magazine.com Editorial: February 2019 John Joseph Adams | 153 words Welcome to issue seventy-seven of Nightmare! We’re opening this month with an original short from Micah Dean Hicks, “Quiet the Dead,” the story of a haunted family in a town whose biggest industry is the pig slaughterhouse. Rafeeat Aliyu’s new short story “58 Rules To Ensure Your Husband Loves You Forever” is full of good relationship advice . if you don’t mind feeding your husband human flesh. We’re also sharing reprints by Kelley Armstrong (“We Are All Monsters Here”) and Nick Mamatas (“The Glottal Stop”). Our nonfiction team has put together their usual array of author spotlights, and in the latest installment of “The H Word,” Richard Thomas talks about exciting new trends in horror films. Since it’s Women in Horror Month, Lisa Morton has put together a terrific panel interview with Linda Addison, Joanna Parypinski, Becky Spratford, and Kaaron Warren—a great group of female writers and scholars. -

Jiwei Ci Vi CONTENTS

CONTEMPORARY CHINESE PHILOSOPHY Edited by CHUNG-YING CHENG AND NICHOLAS BUNNIN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE PHILOSOPHY Dedicated to my mother Mrs Cheng Hsu Wen-shu and the memory of my father Professor Cheng Ti-hsien Chung-ying Cheng Dedicated to my granddaughter Amber Bunnin Nicholas Bunnin CONTEMPORARY CHINESE PHILOSOPHY Edited by CHUNG-YING CHENG AND NICHOLAS BUNNIN Copyright © Blackwell Publishers Ltd 2002 First published 2002 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Blackwell Publishers Inc. 350 Main Street Malden, Massachusetts 02148 USA Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford OX4 1JF UK All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Contemporary chinese philosophy / edited by Chung-ying Cheng and Nicholas Bunnin p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-631-21724-X (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-631-21725-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Philosophy, Chinese—20th century. I. Cheng, Zhongying, 1935– II. -

New School Plan Keeps the Local Program Started in 1972 for Human Development, Sexuality and Grades 4,5 and 6

Rage 16 CRANFORD iti%) CHRONICLE Thursday, February 21. 1980 Crawford's Way Ahead 0i Garwood budget shows Schooltime: more on four point hike; the new/gym program, ^ Ed Kenilworth's OKed plus Greek mythology Page~2\ ~ ; ,..-._.,1^ Page 9 The new state school board niandate education in grade 11 to develop courses in1 family life is npl Since no administrative^ guidelifltes have been issued yet byu the state, expected to require much adjustment USI'S KUi 80(1 S<-corld Class PoMage P;iid Cranford, N.J. 20CKNTS inCraiiford. The family living program Robert D. Paul, schools superintendent,, VOfa. 87 No, g^Published Every Thursday Thursday, February 28', 198(1 Serving (Inmfprd, Kcmhvorth ittui (>nnvo/xl started here eight years ago after said he "assumes we are in compliance,'1 considerable debate. , - - butvvill have to gear up for K to 3." The state will require,,however, a The regulations call for local districts curriculum for grades K to 12. Cranford to provide family life < education by currently starts "tiie-i>pogram in the September 1981v including the In Our fourth grade . • physiological and psychological basis of - New school plan keeps The local program started in 1972 for human development, sexuality and grades 4,5 and 6. The family living units repr/ctdfjctiofn. • a ' : • """'" ' ' "•'.'" - .'•-•• " ' • for grades 7,8 and 9'were introduced in Accq|dirig to legislation signed by 1973 in the health programs. There is a Gpv.,ByrneMonday, parents with moral detailed family living curriculum again or^ religious convictions against sex. in grade 12 after a lapse for first aid and • education, may have their children drug education in grade 10 aod driver's excusetT '. -

Winter Holiday Self-Care

Winter Holiday Self-Care 2 Self-Care for the Winter Holiday Season Adapted from: http://www.lifecoachingcenterstone.org/self-care-for-the-holidays/ It would be great if each of us was able to experience the winter months as “the most wonderful time of the year.” The approach of the winter season often brings expectations of perfect family gatherings, holiday magic, and picture-perfect moments. Yet, we know that for many of us, idealized expectations can lead to frustration, loneliness, disappointment, anxiety, sadness and holiday blues. For those of us who may dread the winter holiday season, the reality of life simply contrasts too greatly with a fairy-tale dream –a dream that we carry ourselves, or that others have built for us, or that others carry for themselves. Question: What does the winter holiday season mean for you? Do you dread it? Look forward to it? Couldn’t care less? __________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ -

III M *III~II~II 4 5 C ~II C a 2 9 5 *~

Date Printed: 06/11/2009 JTS Box Number: IFES 74 Tab Number: 18 Document Title: All Around Kentucky Document Date: Sep-98 Document Country: United States - Kentucky Document Language: English IFES ID: CE02255 III m *III~II~II 4 5 C ~II C A 2 9 5 *~ , VOL. 62, NO.5 SEPTEMBER,1998 Market questions overhang improved political outlook he political outlook for tobac tine content of cigarettes and chew Tco has taken a remarkable ing tobacco, restrict the industry's upturn over the past 60 days, on advertising and extract huge sums the heels of favorable court rulings of money from manufacturers to and a stalemate in Congress. fund ambitious anti-smoking cam But the improvements on the paigns. policy side now may take a back The secondhand smoke decision, seat to concerns about the com though more lightly reported in the modity's commercial prospects, as. media, was signficant for the. brak farmers continue to harvest a crop ing effect it had on the govern that may be more than buyers ment's attempts to virtually ban need .. indoor smoking. On the plus side, two recent There the court said that EPA court victories have given an enor had jury-rigged its research, mous boost to the morale oftobacco throwing out findings that contra partisans. Within weeks of each dicted its anti-smoking bias and other, federal judges in separate lowered its own standard of proof 'SJIra.gu,~ pODSe' with the team for a picture thaZpdorTUJ a new full color poster, cases invalidated the Food and to validate its classification deci 'sp.om;or"d by Farm Bureau (lnd distributed {hrough county offices, at the .Drug~dministration's attempt to .sion. -

Canterbury NEWS & DIRECTORY FOLLOW US on FACEBOOK and Villages

NEWS AND DIRECTORY [email protected] | 01227 392702 01227 392702 Canterbury NEWS & DIRECTORY FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK and Villages WINTER 2018 Please mention Canterbury News & Directory when responding to these ads 1 NEWS AND DIRECTORY [email protected] | 01227 392702 NEWS AND DIRECTORY [email protected] | 01227 392702 ADVERTORIAL Has Your Double NEWS & DIRECTORY It’s my pleasure to welcome you to this Glazing Steamed Up? first issue of our Canterbury Villages title. When we started News & Directory, this Established for over a whole window including With years of experience wonderful part of the world was always in decade Cloudy2Clear the frames and all the Cloudy2Clear have a mind and it’s been fantastic to spread our windows have become hardware, however wealth of knowledge wings and venture into our cathedral city and a leading company Cloudy2Clear have come and are recognised as a Cloudy2Clear the beautiful villages that surround it. for glass replacement. up with a simple and cost Which Trusted Trader, GUARANTEE All Issues with double saving solution… Just plus our work is backed Customers That An We hope you make the most of any time glazing can often be replace the glass!! by an industry leading Average Quote Will off during the festive period and our events gradual and may only 25 year guarantee. Take No Longer page should point you in the direction of be noticed during a clear If you see condensation Cloudy2Clear also some splendid goings on in the city and Than 20 MINS!!! sunny day or during the in your windows just replace faulty locks beyond, including some fun with old Kris winter. -

Sayuri Arai Dissertation Final Final Final

© 2016 Sayuri Arai MEMORIES OF RACE: REPRESENTATIONS OF MIXED RACE PEOPLE IN GIRLS’ COMIC MAGAZINES IN POST-OCCUPATION JAPAN BY SAYURI ARAI DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Chapmpaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Clifford G. Christians, Chair Professor Cameron R. McCarthy Professor David R. Roediger, The University of Kansas Professor John G. Russell, Gifu University ABSTRACT As the number of mixed race people grows in Japan, anxieties about miscegenation in today’s context of intensified globalization continue to increase. Indeed, the multiracial reality has recently gotten attention and led to heightened discussions surrounding it in Japanese society, specifically, in the media. Despite the fact that race mixing is not a new phenomenon even in “homogeneous” Japan, where the presence of multiracial people has challenged the prevailing notion of Japaneseness, racially mixed people have been a largely neglected group in both scholarly literature and in wider Japanese society. My dissertation project offers a remedy for this absence by focusing on representations of mixed race people in postwar Japanese popular culture. During and after the U.S. Occupation of Japan (1945-1952), significant numbers of racially mixed children were born of relationships between Japanese women and American servicemen. American-Japanese mixed race children, as products of the occupation, reminded the Japanese of their war defeat. Miscegenation and mixed race people came to be problematized in the immediate postwar years. In the 1960s, when Japan experienced the postwar economic miracle and redefined itself as a great power, mixed race Japanese entertainers (e.g., models, actors, and singers) became popular. -

![Fairy Inc. Sheet Music Products List Last Updated [2013/03/018] Price (Japanese Yen) a \525 B \788 C \683](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1957/fairy-inc-sheet-music-products-list-last-updated-2013-03-018-price-japanese-yen-a-525-b-788-c-683-4041957.webp)

Fairy Inc. Sheet Music Products List Last Updated [2013/03/018] Price (Japanese Yen) a \525 B \788 C \683

Fairy inc. Sheet Music Products list Last updated [2013/03/018] Price (Japanese Yen) A \525 B \788 C \683 ST : Standard Version , OD : On Demand Version , OD-PS : Piano solo , OD-PV : Piano & Vocal , OD-GS : Guitar solo , OD-GV : Guitar & Vocal A Band Score Piano Guitar Title Artist Tie-up ST OD ST OD-PS OD-PV ST OD-GS OD-GV A I SHI TE RU no Sign~Watashitachi no Shochiku Distributed film "Mirai Yosouzu ~A I DREAMS COME TRUE A A A Mirai Yosouzu~ SHI TE RU no Sign~" Theme song OLIVIA a little pain - B A A A A inspi'REIRA(TRAPNEST) A Song For James ELLEGARDEN From the album "BRING YOUR BOARD!!" B a walk in the park Amuro Namie - A a Wish to the Moon Joe Hisaishi - A A~Yokatta Hana*Hana - A A Aa Superfly 13th Single A A A Aa Hatsu Koi 3B LAB.☆ - B Aa, Seishun no Hibi Yuzu - B Abakareta Sekai thee michelle gun elephant - B Abayo Courreges tact, BABY... Kishidan - B abnormalize Rin Toshite Shigure Anime"PSYCHO-PASS" Opening theme B B Acro no Oka Dir en grey - B Acropolis ELLEGARDEN From the album "ELEVEN FIRE CRACKERS" B Addicted ELLEGARDEN From the album "Pepperoni Quattro" B ASIAN KUNG-FU After Dark - B GENERATION again YUI Anime "Fullmetal Alchemist" Opening theme A B A A A A A A Again 2 Yuzu - B again×again miwa From 2nd album "guitarium" B B Ageha Cho PornoGraffitti - B Ai desita. Kan Jani Eight TBS Thursday drama 9 "Papadoru!" Theme song B B A A A Ai ga Yobu Hou e PornoGraffitti - B A A Ai Nanda V6 - A Ai no Ai no Hoshi the brilliant green - B Ai no Bakudan B'z - B Ai no Kisetsu Angela Aki NHK TV novel series "Tsubasa" Theme song A A -

THE KNOWING a Fantasy by Kevan Manwaring

APPENDICES Novel (cont.) Kevan Manwaring THE KNOWING A Fantasy by Kevan Manwaring (Continued from Section Two: Creative Component) Submission for a Creative Writing PhD University of Leicester June 2018 Supervisor: Dr Harry Whitehead Student Number: 129044809 ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1756-5222 www.thesecretcommonwealth.com Page 1 APPENDICES Novel (cont.) Kevan Manwaring REMINDER TO EXAMINERS Motifs are included that relate to supplementary narrative voices, which can be viewed via the website (www.thesecretcommonwealth.com). See ‘Discover the McEttrick Women’ and ‘Discover the Characters’. The novel can be read without referring to these, but it may enhance your experience, if you wish to know more. Additional material is also available on the website: other voices from the world of the novel; audio and video recordings; original artwork; articles (by me as a research- practitioner); photographs of field research; a biographical comic strip about Rev. Robert Kirk; and so on. Collectively, this constitutes the totality of my research project. www.thesecretcommonwealth.com Page 2 APPENDICES Novel (cont.) Kevan Manwaring 22 Janey awoke with a jolt. Turbulence again. Felt like they were riding through a storm. Jim Morrison eat your heart out, she groaned to herself. Being cooped up in a soup can in the sky for hours on end felt like the very opposite of rock'n'roll. All but the safety lights were out. Around her, a small village of strangers slept above the clouds, swaddled in cellophane-static blankets, commode cushions and flight socks. She tried to stretch, but there just wasn't enough leg room for someone like her. -

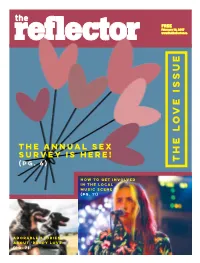

Reflector-Feb.-16-2017Mini.Pdf

the FREE FREE FebruaryFebruary 16, 2017 16, 2017 reflector www.TheReflector.cawww.TheReflector.ca ISSUE LOVE The annual sex survey is here! THE (PG. 6) How to get involved in the local music scene. (Pg. 11) Adorable stories about ‘puppy love.’ (Pg. 7) News Editor Jennifer Dorozio news [email protected] PAN Calgary exists to equalize the abortion rights debate U of C Club aims to counter-protest triggering pro-life signage on campus Sydney Fritz and supporters. This helps to such as Jews in the Holocaust or Staff Writer mobilize group demonstrations or African-Americans during the Civil “counter protests” as she calls them, Rights struggle in the US.” The The pro-life vs. pro-choice debate and provide support for people who GAP website says this is done to has been causing a stir on campuses have negative reactions to some of stimulate “dialogue among students across Canada for a long time. But the more graphic pro-life displays. and others who ordinarily ignore the Pro Choice Activist Network Calgary She says they do so, “to show abortion debate” and to “humanize (PAN Calgary) has made the choice- students and community members the pre-born and dehumanize side of the debate far more visible that they are not alone and to show abortion.” on the University of Calgary (U of that there is support for the Pro- Currently, PAN Calgary is most C) campus. Choice movement on campus.” active at the U of C, however the PAN Calgary is a rising activist “While counter-protesting we will group is looking to expand to MRU.