(Crustacea: Decapoda) and Its Impact on the Anomura

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Classification of Living and Fossil Genera of Decapod Crustaceans

RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2009 Supplement No. 21: 1–109 Date of Publication: 15 Sep.2009 © National University of Singapore A CLASSIFICATION OF LIVING AND FOSSIL GENERA OF DECAPOD CRUSTACEANS Sammy De Grave1, N. Dean Pentcheff 2, Shane T. Ahyong3, Tin-Yam Chan4, Keith A. Crandall5, Peter C. Dworschak6, Darryl L. Felder7, Rodney M. Feldmann8, Charles H. J. M. Fransen9, Laura Y. D. Goulding1, Rafael Lemaitre10, Martyn E. Y. Low11, Joel W. Martin2, Peter K. L. Ng11, Carrie E. Schweitzer12, S. H. Tan11, Dale Tshudy13, Regina Wetzer2 1Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PW, United Kingdom [email protected] [email protected] 2Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90007 United States of America [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3Marine Biodiversity and Biosecurity, NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Kilbirnie Wellington, New Zealand [email protected] 4Institute of Marine Biology, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung 20224, Taiwan, Republic of China [email protected] 5Department of Biology and Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602 United States of America [email protected] 6Dritte Zoologische Abteilung, Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien, Austria [email protected] 7Department of Biology, University of Louisiana, Lafayette, LA 70504 United States of America [email protected] 8Department of Geology, Kent State University, Kent, OH 44242 United States of America [email protected] 9Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum, P. O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands [email protected] 10Invertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, 10th and Constitution Avenue, Washington, DC 20560 United States of America [email protected] 11Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 12Department of Geology, Kent State University Stark Campus, 6000 Frank Ave. -

Crustacea, Decapoda, Brachyura) Danièle Guinot

New hypotheses concerning the earliest brachyurans (Crustacea, Decapoda, Brachyura) Danièle Guinot To cite this version: Danièle Guinot. New hypotheses concerning the earliest brachyurans (Crustacea, Decapoda, Brachyura). Geodiversitas, Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle Paris, 2019, 41 (1), pp.747. 10.5252/geodiversitas2019v41a22. hal-02408863 HAL Id: hal-02408863 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-02408863 Submitted on 13 Dec 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Changer fig. 19 initiale Inverser les figs 15-16 New hypotheses concerning the earliest brachyurans (Crustacea, Decapoda, Brachyura) Danièle GUINOT ISYEB (CNRS, MNHN, EPHE, Sorbonne Université), Institut Systématique Évolution Biodiversité, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, case postale 53, 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris cedex 05 (France) [email protected] An epistemological obstacle will encrust any knowledge that is not questioned. Intellectual habits that were once useful and healthy can, in the long run, hamper research Gaston Bachelard, The Formation of the Scientific -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 02:14:49PM Via Free Access B.M

Contributions to Zoology, 72 (2-3) 83-84 (2003) SPB Academic Publishing bv, The Hague An interesting case of homonymy: Notopus de Haan, 1841 (Crustacea, Raninidae; Recent) and Notopus Leonardi, 1983 (ichnofossil; Devonian) ³ Barry+W.M. van Bakel¹, John+W.M. Jagt² & René+H.B. Fraaije 1 2 Schepenhoek 235, NL-5403 GB Uden, the Netherlands; Natuurhistorisch Museum Maastricht, de 3 Bosquetplein 6-7, P.O. Box 882, NL-6200 AW Maastricht, the Netherlands; Oertijdmuseum de Groene Poort, Bosscheweg 80, NL-5283 WB Boxtel, the Netherlands Keywords: Homonymy, Crustacea, ichnofossils, Notopus Abstract N. petri, involves an ichnofossil from the Devonian of Paran-, Brazil (Leeonardi, 1983: 236). Leonard! Upper Cretaceous strata in the type area of the Maastrichtian interpreted this as the imprint of the left front limb Stage Netherlands, NE have yielded (SE Belgium) compara- of an amphibian. Roek & Rage (1994), who restudied tively abundant and diverse raninid assemblages (Collins et al., Leonardos .original material, were of the opinion 1995; Fraaye & van Bakel, 1998). To date, seven species are that this ichnofossil taxon did not represent part of known: Eumorphocorystes sculptus, Pseudoraninella muelleri, but rather similar to Lyreidinapyriformis, Raninoides? quadrispinosus,Raniliformis an amphibian trackway, was asteroid chevrona, Raniliformis prebaltica and Raniliformis occlusa. traces of an or ophiuroid, comparable to These Maastricht occur mainly from the portion of the Asteriacites upper the ichnofossil genus von Schlotheim. Formation[Emael, Nekum andMeerssen members, Belemnitella Irrespective of the correct assignment of this junior and Belemnella (Neobelemnella) kazimiroviensis bio- ichnotaxon, Notopus Leonard!, 1983 (non de Haan, zones]. is in need of substitute the 1841) a name, more so with since ichnotaxon names compete (palaeo)zoo- taxa June Introduction logical (A.K. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/11/2021 08:33:28AM Via Free Access 224 E

Contributions to Zoology, 67 (4) 223-235 (1998) SPB Academic Publishing bv, Amsterdam Optics and phylogeny: is there an insight? The evolution of superposition eyes in the Decapoda (Crustacea) Edward Gaten Department of Biology, University’ ofLeicester, Leicester LEI 7RH, U.K. E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Compound eyes, superposition optics, adaptation, evolution, decapod crustaceans, phylogeny Abstract cannot normally be predicted by external exami- nation alone, and usually microscopic investiga- This addresses the of structure and in paper use eye optics the tion of properly fixed optical elements is required construction of and crustacean phylogenies presents an hypoth- for a complete diagnosis. This largely rules out esis for the evolution of in the superposition eyes Decapoda, the use of fossil material in the based the of in comparatively on distribution eye types extant decapod fami- few lies. It that arthropodan specimens where the are is suggested reflecting superposition optics are eyes symplesiomorphic for the Decapoda, having evolved only preserved (Glaessner, 1969), although the optics once, probably in the Devonian. loss of Subsequent reflecting of some species of trilobite have been described has superposition optics occurred following the adoption of a (Clarkson & Levi-Setti, 1975). Also the require- new habitat (e.g. Aristeidae,Aeglidae) or by progenetic paedo- ment for good fixation and the fact that complete morphosis (Paguroidea, Eubrachyura). examination invariably involves the destruction of the specimen means that museum collections Introduction rarely reveal enough information to define the optics unequivocally. Where the optics of the The is one of the compound eye most complex component parts of the eye are under investiga- and remarkable not on of its fixation organs, only account tion, specialised to preserve the refrac- but also for the optical precision, diversity of tive properties must be used (Oaten, 1994). -

Brachyura, Majoidea) Genera Acanthonyx Latreille, 1828 and Epialtus H

Nauplius 20(2): 179-186, 2012 179 Range extensions along western Atlantic for Epialtidae crabs (Brachyura, Majoidea) genera Acanthonyx Latreille, 1828 and Epialtus H. Milne Edwards, 1834 Ana Francisca Tamburus and Fernando L. Mantelatto Laboratory of Bioecology and Crustacean Systematics (LBSC) - Postgraduate Program in Comparative Biology - Department of Biology - Faculty of Philosophy, Sciences and Letters of Ribeirão Preto (FFCLRP) - University of São Paulo (USP). Av. Bandeirantes 3900, CEP 14040- 901, Ribeirão Preto (SP), Brazil. E-mails: (AFT) [email protected]; (FLM) [email protected] Abstract The present study provided information extending the known geographical distribution of three species of majoid crabs, the epialtids Acanthonyx dissimulatus Coelho, 1993, Epialtus bituberculatus H. Milne Edwards, 1834, and E. brasiliensis Dana, 1852. Specimens of both genera from different carcinological collections were studied by comparing morphological characters. We provide new data that extends the geographical distributions of E. bituberculatus to the coast of the states of Paraná and Santa Catarina (Brazil), and offer new records from Belize and Costa Rica. Epialtus brasiliensis is recorded for the first time in the state of Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil), and A. dissimulatus is reported from Quintana Roo, Mexico. The distribution of A. dissimulatus, previously known as endemic to Brazil, has a gap between the states of Espírito Santo and Rio de Janeiro. However, this restricted southern distribution is herein amplified by the Mexican specimens. Key words: Geographic distribution, majoid, new records, spider crabs. Introduction (Melo, 1996). Epialtus bituberculatus H. Milne Edwards, 1834 has been from Florida (USA), The family Epialtidae MacLeay, 1838 Gulf of Mexico, West Indies, Colombia, includes 76 genera, among them Acanthonyx Venezuela and Brazil (Ceará to São Paulo Latreille, 1828 and Epialtus H. -

Part I. an Annotated Checklist of Extant Brachyuran Crabs of the World

THE RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2008 17: 1–286 Date of Publication: 31 Jan.2008 © National University of Singapore SYSTEMA BRACHYURORUM: PART I. AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF EXTANT BRACHYURAN CRABS OF THE WORLD Peter K. L. Ng Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Kent Ridge, Singapore 119260, Republic of Singapore Email: [email protected] Danièle Guinot Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Département Milieux et peuplements aquatiques, 61 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France Email: [email protected] Peter J. F. Davie Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT. – An annotated checklist of the extant brachyuran crabs of the world is presented for the first time. Over 10,500 names are treated including 6,793 valid species and subspecies (with 1,907 primary synonyms), 1,271 genera and subgenera (with 393 primary synonyms), 93 families and 38 superfamilies. Nomenclatural and taxonomic problems are reviewed in detail, and many resolved. Detailed notes and references are provided where necessary. The constitution of a large number of families and superfamilies is discussed in detail, with the positions of some taxa rearranged in an attempt to form a stable base for future taxonomic studies. This is the first time the nomenclature of any large group of decapod crustaceans has been examined in such detail. KEY WORDS. – Annotated checklist, crabs of the world, Brachyura, systematics, nomenclature. CONTENTS Preamble .................................................................................. 3 Family Cymonomidae .......................................... 32 Caveats and acknowledgements ............................................... 5 Family Phyllotymolinidae .................................... 32 Introduction .............................................................................. 6 Superfamily DROMIOIDEA ..................................... 33 The higher classification of the Brachyura ........................ -

Population Structure, Recruitment, and Mortality of the Freshwater Crab Dilocarcinus Pagei Stimpson, 1861 (Brachyura, Trichodactylidae) in Southeastern Brazil

Invertebrate Reproduction & Development ISSN: 0792-4259 (Print) 2157-0272 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tinv20 Population structure, recruitment, and mortality of the freshwater crab Dilocarcinus pagei Stimpson, 1861 (Brachyura, Trichodactylidae) in Southeastern Brazil Fabiano Gazzi Taddei, Thiago Maia Davanso, Lilian Castiglioni, Daphine Ramiro Herrera, Adilson Fransozo & Rogério Caetano da Costa To cite this article: Fabiano Gazzi Taddei, Thiago Maia Davanso, Lilian Castiglioni, Daphine Ramiro Herrera, Adilson Fransozo & Rogério Caetano da Costa (2015) Population structure, recruitment, and mortality of the freshwater crab Dilocarcinuspagei Stimpson, 1861 (Brachyura, Trichodactylidae) in Southeastern Brazil, Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, 59:4, 189-199, DOI: 10.1080/07924259.2015.1081638 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2015.1081638 Published online: 15 Sep 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 82 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tinv20 Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, 2015 Vol. 59, No. 4, 189–199, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2015.1081638 Population structure, recruitment, and mortality of the freshwater crab Dilocarcinus pagei Stimpson, 1861 (Brachyura, Trichodactylidae) in Southeastern Brazil Fabiano Gazzi Taddeia*, Thiago Maia Davansob, Lilian Castiglionic, Daphine Ramiro Herrerab, Adilson Fransozod and Rogério Caetano da Costab aLaboratório de Estudos de Crustáceos Amazônicos (LECAM), Universidade do Estado do Amazonas – UEA/CESP, Centro de Estudos Superiores de Parintins, Estrada Odovaldo Novo, KM 1, 69152-470 Parintins, AM, Brazil; bFaculdade de Ciências, Laboratório de Estudos de Camarões Marinhos e Dulcícolas (LABCAM), Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Av. -

Notopus Dorsipes (Linnaeus) in Singapore: First Record of the Brachyuran Superfamily Raninoidea (Crustacea: Decapoda) on the Sunda Shelf

NATURE IN SINGAPORE 2012 5: 19–25 Date of Publication: 27 January 2012 © National University of Singapore NOTOPUS DORSIPES (LINNAEUS) IN SINGAPORE: FIRST RECORD OF THE BRACHYURAN SUPERFAMILY RANINOIDEA (CRUSTACEA: DECAPODA) ON THE SUNDA SHELF Martyn E. Y. Low1* and S. K. Tan2 1Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences, Graduate School of Engineering and Science University of the Ryukyus, 1 Senbaru, Nishihara, Okinawa 903-0213, Japan 2Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, National University of Singapore 6 Science Drive 2, Singapore 117546, Republic of Singapore (*Corresponding author: [email protected]) INTRODUCTION Recently, a brachyuran crab identified as Notopus dorsipes (Linnaeus, 1758), was found at Changi (north-east Singapore). This represents the first record of the superfamily Raninoidea de Haan, 1839, in Singapore and on the Sunda Shelf (Figs. 1, 2). The superfamily Raninoidea has a worldwide distribution and its members inhabit marine habitats from the intertidal zone to over 300 m deep (reviewed in Ahyong et al., 2009; see also Dawson & Yaldwyn, 1994). Fifty species of raninoids are currently assigned to 12 genera in six subfamilies (Ng et al., 2008). Notopus dorsipes belongs to a monotypic genus currently assigned to the subfamily Notopodinae Serène & Umali, 1972 (see Ng et al., 2008). Originally described as Cancer dorsipes by Linnaeus (1758), this species has had a confused nomenclatural history (see Holthuis, 1962). In order to stabilise the name Cancer dorsipes Linnaeus, Holthuis (1962: 55) designated a figure in Rumphius (1705: pl. 10: Fig. 3) as the lectotype of Notopus dorsipes (reproduced as Fig. 3). De Haan (1841) established the genus Notopus for Cancer dorsipes Linnaeus, the type species by monotypy. -

How to Become a Crab: Phenotypic Constraints on a Recurring Body Plan

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 25 December 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202012.0664.v1 How to become a crab: Phenotypic constraints on a recurring body plan Joanna M. Wolfe1*, Javier Luque1,2,3, Heather D. Bracken-Grissom4 1 Museum of Comparative Zoology and Department of Organismic & Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford St, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 2 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa–Ancon, 0843–03092, Panama, Panama 3 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520-8109, USA 4 Institute of Environment and Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Biscayne Bay Campus, 3000 NE 151 Street, North Miami, FL 33181, USA * E-mail: [email protected] Summary: A fundamental question in biology is whether phenotypes can be predicted by ecological or genomic rules. For over 140 years, convergent evolution of the crab-like body plan (with a wide and flattened shape, and a bent abdomen) at least five times in decapod crustaceans has been known as ‘carcinization’. The repeated loss of this body plan has been identified as ‘decarcinization’. We offer phylogenetic strategies to include poorly known groups, and direct evidence from fossils, that will resolve the pattern of crab evolution and the degree of phenotypic variation within crabs. Proposed ecological advantages of the crab body are summarized into a hypothesis of phenotypic integration suggesting correlated evolution of the carapace shape and abdomen. Our premise provides fertile ground for future studies of the genomic and developmental basis, and the predictability, of the crab-like body form. Keywords: Crustacea, Anomura, Brachyura, Carcinization, Phylogeny, Convergent evolution, Morphological integration 1 © 2020 by the author(s). -

Fishery Bulletin/U S Dept of Commerce National Oceanic

LARVAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE CUBAN STONE CRAB, MENlPPE NODlFRONS (BRACHYURA, XANTHIDAE), UNDER LABORATORY CONDITIONS WITH NOTES ON THE STATUS OF THE FAMILY MENIPPIDAE1 LumInA E. SCO,I'02 ABSTRACT The complete larval development of the Cuban stone crab, Menippc nodifrons, is described and illustrated. Larvae reared in the laboratory passed through a prezoeal, five and uncommonly six zoeal, and one megalopal stage. At 30" C the megalopal stage was attained in 16-17 clays, at 20" C, 28-37 days. The six zoeal stages of M. nodifrons are compared with those of its sympatric congener M. mcrc<'!laria and with the first zoeal stage of the Indo-Pacific species M. rumphii. Larvae ofthe genus Menippe may be distinguished from other xanthid larvae by a combination of morphological features, including lilltennal development (exopodite at least three-fourths the length ofprotopoditel, lack of setae on the basal segment of the second maxillipL'<!al endopodite, and number oflarval stages (Menippe, 5 or 6; most other xanthids, 4). Using Lebour's criteria (emphasizing antenna! development and number of zoeal stages) to determine the primitive or advancL'<! status of decapod larvae, the genus Menippe is more closely related to the phylogentically primitive family Cancriclae than to most of the Xanthidae. The possible reestablishment of the family Menippidae is discussed in view of new larval evidence. The Cuban stone crab, MCllippe llodij'rolls tions of West Africa (Capart 1951; Monod 1956), a Stimpson 1859, is a medium-sized xanthid crab survey of stomatopod and decapod crustaceans of closely allied to the common commercial stone Portuguese Guiana (Vilela ]951), and an ecologi crab, MCllippc I/lcrcenaria (Say 18] 8). -

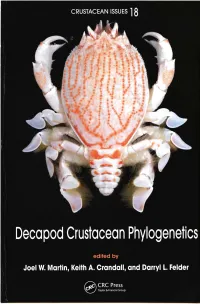

Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics

CRUSTACEAN ISSUES ] 3 II %. m Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics edited by Joel W. Martin, Keith A. Crandall, and Darryl L. Felder £\ CRC Press J Taylor & Francis Group Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics Edited by Joel W. Martin Natural History Museum of L. A. County Los Angeles, California, U.S.A. KeithA.Crandall Brigham Young University Provo,Utah,U.S.A. Darryl L. Felder University of Louisiana Lafayette, Louisiana, U. S. A. CRC Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Croup, an informa business CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300 Boca Raton, Fl. 33487 2742 <r) 2009 by Taylor & Francis Group, I.I.G CRC Press is an imprint of 'Taylor & Francis Group, an In forma business No claim to original U.S. Government works Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 109 8765 43 21 International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-4200-9258-5 (Hardcover) Ibis book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and publisher cannot assume responsibility for the valid ity of all materials or the consequences of their use. The authors and publishers have attempted to trace the copyright holders of all material reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this form has not been obtained. If any copyright material has not been acknowledged please write and let us know so we may rectify in any future reprint. Except as permitted under U.S. Copyright Faw, no part of this book maybe reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or uti lized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopy ing, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/07/2021 01:08:16PM Via Free Access 120 - R.H.B

Contributions to Zoology, 72 (2-3) 119-130 (2003) SPB Academic Publishing bv, The Hague Evolution of reef-associated decapod crustaceans through time, with particular reference to the Maastrichtian type area René+H.B. Fraaije Oertijdmuseum de Groene Poort, Bosscheweg 80, NL-5283 WB Boxtel, the Netherlands Keywords: Decapod crustacean evolution, K/T boundary, biostratigraphy Abstract prior to 1987 by various authors (Bosquet, 1854; van Binkhorst, 1857; Binkhorst van den Binkhorst, The result of of some twenty years intensive collecting from 1861; Noetling, 1881; Pelseneer, 1886;Forir, 1887a- in the strata Maastrichtian type area is a collection ofmore than c, 1889; Mulder, 1981) suffer from a lack of strati- 1,200 generally small-sized anomuranand brachyuran remains. graphic control. A taxonomic revision of most of The of the stratigraphical ranges thirty-one species known to these was carried out Collins al. date species by et (1995). from the Maastricht Formation (Late Maastrichtian) are shown Since 1987, new from the Maastrichtian and five successive decapod assemblages are discussed. species For the first time, crustacean to decapod remains now turn out type area were described and discussed by Fraaye be useful biostratigraphic tools on a local to regional scale. & Collins (1987), Feldmann et al. (1990), Jagt et al. (1991, 1993), Collins et al. (1995), Fraaye (1996 a-c, 2002), Fraaye & van Bakel (1998) and Jagt et Introduction al. (2000). Rigid collecting from six key sections (see Collins Brachyurans utilize a broad of feeding types, array et al. 1995, p. 168, fig. 1) during the past two de- including deposit feeding, filter feeding, seaweed cades has resulted in an extensive, stratigraphically grazing, and have been scavenging predation.