A History of Maine Audubon by Herb Adams This First Appeared in Habitat As a Series of Articles in 1986 and Then Was Reprinted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Massachusetts Off Fernandina Sept. 4 [1862]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1556/massachusetts-off-fernandina-sept-4-1862-441556.webp)

Massachusetts Off Fernandina Sept. 4 [1862]

Massachusetts Off Fernandina Sept. 4 [1862] I am so sorry that we could not communicate with you off St. Johns especially as you are covering yourself all over with glory. We arrived off the mouth of the river yesterday at 5 pm. This morning the Cimmaron’s Launch came off and I could not obtain any satisfactory information from the officer; therefore I thought it advisable to chase the Uncas up to this place and freight her with the fresh supplies for your flat which I hope will meet with your approbation and send you a large supply of Ice. Captain Godon [S.W. Godon] whose headquarters are on board of the Vermont- the Admiral having gone home- is anxious to get this ship North with the news about your success. Every little helps the Cause at this time. I sent in by the Boat this morning a file of papers for you containing all the enlisting news. Now for the Trunk it has been put on board of the liner Baldwin sent it on board of this ship at Port Royal, with the baggage of the officers and crew of the Adirondack. No message or word to me of course it was put below in the hold, and fortunately I received your note in New York and trust it will reach you safely, thanks to you for wishing me a better command. The Dept. [Department] have promised me one, when they can find a relief for me in this trade perhaps I may be detached on my return. I am tired of coasting and being a [Butcher?] however as long as I am here you must command my services. -

George Henry Preble

AIfl RCAh uTI UiT iOJLT ianuscrit Co1leoioi of ccl1sotiot. Location; Octave volumes “P” c..l861—c.l882 Folio volumes “P” Preble, George Henry, Papers, Misc. mss. boxes “P” of collcouon; number 6 octavo volumes; 1 folio volume; 2 folders, 32 items 62—3056 H ails. See DAB, vol. 15, pp. 183-814; and AAS Proceedings, vol. 3 (October 1883-April 1885), pp. 392 and 1495-500. •oiozce of coilec iou Gift and bequest of George Henry Preble Collection Description. George Henry Preble (1816-1885) was a naval officer and author, He served with the Navy in the Mediterranean and Caribbean. From l8L3 to i8L5 he circumnavigated I the world and went ashore with the first American force to land in China. He also sailed with Matthew C. Perry’s expedition to the Far East in 1852 to l85L. He served. in various capacities with the Navy during the Civil War and retired as a rear admiral. Preble was a writer and collector of material on historical subjects, epeciall naval topics. He wrote Our Flag: Origin and Progress of thl of the United States of America... (1872, 1880, and 1917). He also researched his genealogy and wrote many historical sketches and periodical articles. The first four octavo volumes are collections of correspondence, newsclippings, illustrations, photographs, and business records pertaining to his research for the book on the American flag. The materials are not arranged in a precise order but appear to be grouped together in non-alphabetical sequence by writer. The first volume includes material dating from 1861—1873; the second, 1866—1873; the third, 1873—1880; and the fourth, 1873—1880. -

The Chase of the Rebel Steamer of War Oreto (1862)

THE ^cf^ip CHASE REBEL STEAMER OF WAR ORETO, COMMANDER J. N. MAFFITT, C. S. N. BA^Y OF MOBILE NITEl) STATES STEAM SLOOP ONEIDA, COMMANDER GEO. HENRY PREBLE, U. S. N. SEPTEMBER 4. 1862. CAMBRIDGE: PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCUEATION 18 6 2. Class /r^-g^^f"- Book > F(o T9__ : THE CHASE REBEL STEAMER OF WAR ORETO, COMMANDEE J. N. MAFFITT, C. S. N. BA.Y OF ]M:0BILE, UNITED STATES STEAM SLOOP ONEIDA, COMMANDER GEO. HENRY EREBLE, U. S. N. SEPTEMBER 4, 1862. " Good name in man or woman, dear, my lord, Is the immediate jewel of their soul Who steals my purse, steals trash ; 'tis something, nothing; 'Twas mine, 'tis his, and slave to thousands has been ; But he that filches from me my good name, Robs me of that which not enriches him, And makes me poor indeed." Othello, — Act III. CAMBRIDGE: PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION. 18 6 2. CAMBRIDGE: Allen and Farnham, Printers. : CHASE OF THE REBEL WAR STEAMER ORETO BLOCKADING FOECE OPr MOBILE, SEPTEMBER 4, 1862. COMMANDER PREBLE'S FIRST REPORT OF THE CHASE OF THE ORETO, SEPTEMBER 4, 1862. United States Steam Sloop Oneida, ") Off Mobile, Sept. 4, 1862. | Sir, — I regret having to inform you that a three master screw steamer, bearing an English red ensign and pennant, and carrying four quarter boats and a battery of six or eight broadside guns and one or two pivots, and hav- ing every appearance of an English man-of-war, ran the blockade this after- noon under the following circumstances I had sent the Winona to the westward to speak a schooner standing in under sail, when the smoke of a steamer was discovered bearing about south- east, and standing directly for us. -

Naval Officers Their Heredity and Development

#^ fer^NTS, M^t v y ^ , . r - i!\' \! I III •F UND-B EQUEATlli:h-BY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Open Knowledge Commons and Harvard Medical School http://www.archive.org/details/navalofficerstheOOdave NAVAL OFFICERS THEIR HEREDITY AND DEVELOPMENT >' BY CHARLES BENEDICT DAVENPORT DIBECTOR OF DEPARTMENT OF EXPERIMENTAL EVOLUTION AND OF THE EUGENICS RECORD OFFICE, CARNEGIE INSTITUTION OF WASHINGTON ASSISTED BY MARY THERESA SCUDDER RESEARCH COLLABORATOR IN THE CARNEGIE INSTITUTION OF WASHINGTON Published by the Carnegie Institution of Washington Washington, 1919 CARNEGIE INSTITUTION OF WASHINGTON Publication No. 259 Paper No. 29 op the Station for Experimental Evolution at Cold Spring Harbor, New York : THE-PLIMPTON-PEESS NORWOOD- MAS S-U-S-A TABLE OF CONTENTS. Part i. PAGE I. Statement of Problem 1 II. An Improved Method op Testing the Fitness op Untried Officers .... 2 1. General Considerations 2 2. Special Procedure 3 III. Results of Study 4 1. Types of Naval Officers 4 2. Temperament in Relation to Type 4 3. Juvenile Promise of Naval Officers of the Various Types 6 Fighters 6 Strategists 7 Administrators 7 Explorers 8 Adventurers 8 Conclusion as to Juvenile Promise 8 4. The Hereditary Traits of Naval Officers 9 General 9 The Inheritance of Special Traits 25 Thalassophilia, or Love of the Sea 25 Source of Thalassophilia (or Sea-lust) in Naval Officers . 25 Heredity of Sea-lust 27 The Hyperkinetic Qualities of the Fighters 29 Source of Nomadism in Naval Officers 31 IV. Conclusions 33 V. Application of Principles to Selection of Untried Men 33 PART II. -

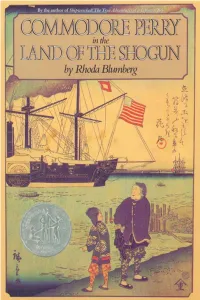

COMMODORE PERRY in the LAND of the SHOGUN

COMMODORE PERRY in the LAND OF THE SHOGUN by Rhoda Blumberg For my husband, Gerald and my son, Lawrence I want to thank my friend Dorothy Segall, who helped me acquire some of the illustrations and supplied me with source material from her private library. I'm also grateful for the guidance of another dear friend Amy Poster, Associate Curator of Oriental Art at the Brooklyn Museum. · Table of Contents Part I The Coming of the Barbarians 11 1 Aliens Arrive 13 2 The Black Ships of the Evil Men 17 3 His High and Mighty Mysteriousness 23 4 Landing on Sacred Soil The Audience Hall 30 5 The Dutch Island Prison 37 6 Foreigners Forbidden 41 7 The Great Peace The Emperor · The Shogun · The Lords · Samurai · Farmers · Artisans and Merchants 44 8 Clouds Over the Land of the Rising Sun The Japanese-American 54 Part II The Return of the Barbarians 61 9 The Black Ships Return Parties 63 10 The Treaty House 69 11 An Array Of Gifts Gifts for the Japanese · Gifts for the Americans 78 12 The Grand Banquet 87 13 The Treaty A Japanese Feast 92 14 Excursions on Land and Sea A Birthday Cruise 97 15 Shore Leave Shimoda · Hakodate 100 16 In The Wake of the Black Ships 107 AfterWord The First American Consul · The Fall of the Shogun 112 Appendices A Letter of the President of the United States to the Emperor of Japan 121 B Translation of Answer to the President's Letter, Signed by Yenosuke 126 C Some of the American Presents for the Japanese 128 D Some of the Japanese Presents for the Americans 132 E Text of the Treaty of Kanagawa 135 Notes 137 About the Illustrations 144 Bibliography 145 Index 147 About the Author Other Books by Rhoda Blumberg Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher Steamships were new to the Japanese. -

A Navy in the New Republic: Strategic Visions of the U.S

ABSTRACT Title of Document: A NAVY IN THE NEW REPUBLIC: STRATEGIC VISIONS OF THE U.S. NAVY, 1783-1812 Joseph Payne Slaughter II, Master of Arts, 2006 Directed By: Associate Professor Whitman Ridgway Department of History This study examines the years 1783-1812 in order to identify how the Founders’ strategic visions of an American navy were an extension of the debate over the newly forming identity of the young republic. Naval historiography has both ignored the implications of a republican navy and oversimplified the formation of the navy into a bifurcated debate between Federalists and Republicans or “Navalists” and “Antinavalists.” The Founders’ views were much more complex and formed four competing strategic visions-commerce navy, coastal navy, regional navy, and capital navy. The thematic approach of this study connects strategic visions to the narrative of the reestablishment of the United States Navy within the context of international and domestic events. This approach leaves one with a greater sense that the early national period policymakers were in fact fledgling naval visionaries, nearly one hundred years before the advent of America’s most celebrated naval strategist, Alfred Thayer Mahan. A NAVY IN THE NEW REPUBLIC: STRATEGIC VISIONS OF THE U.S. NAVY, 1783-1812 By Joseph Payne Slaughter II Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2006 Advisory Committee: Professor Whitman Ridgway, Chair Professor James Henretta Professor Jon Tetsuro Sumida © Copyright by Joseph Payne Slaughter II 2006 Acknowledgements Many thanks to Dr. -

Smithsonian Collections from Commodore Matthew Perry's Japan Expedition (1853-1854)

Artifacts of Diplomacy: Smithsonian Collections from Commodore Matthew Perry's Japan Expedition (1853-1854) CHANG-SU HOUCHINS SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ANTHROPOLOGY • NUMBER 37 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through trie years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

A Canoe Expedition Into the Everglades in 1842* by GEORGE HENRY PREBLE Rear Admiral USN, Z8z6-1885

A Canoe Expedition Into the Everglades in 1842* by GEORGE HENRY PREBLE Rear Admiral USN, z8z6-1885. THE FOLLOWING PAGES are a verbatim transcript of a penciled memorandum of events made by me from day to day while on an expedition across the Everglades, around Lake Okeechobee, and up and down the connecting rivers and lakes, in 1842. Now that it is proposed to drain the Everglades and open them to cultivation, and a dredge-boat is actually at work excavating a navigable outlet into Lake Okeechobee, this diary, which preserves some of the features of the country forty years ago, may have more or less historical interest. A New Orleans newspaper (The Times Democrat) describing the route of a party of surveyors, who had recently gone over very much the same routes as this expedition of 1842, only in reverse, states that it is the first time these regions have been traversed by white men, evi- dently a mistake, as even this expedition of forty years previous was not the first that had visited Lake Okeechobee. General Taylor's battle was fought on the shores of that lake in 1837, and the Everglades had been traversed and retraversed by the expeditions of the army and navy before that. Sprague's "History of the Florida War," published in 1848, is the only work that mentions the services of the navy in that connection, and in its appendix there are tables exhibiting the casualties of the offi- cers, seamen, and marines of the United States navy operating against the Indians in Florida, and of the officers and marines who were brev- etted. -

Tequesta : Number 5/1945

•• THE JOURNAL OF THE HISTORICAL &eI Cetsc ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHERN FLORIDA Editor: Leonard R. Muller CONTENTS PAGE Flagler Before Florida 3 Sidney Walter Martin Blockade-Running in the Bahamas during the Civil War 16 Thelma Peters A Canoe Expedition into the Everglades in 1842 30 George Henry Preble Three Floridian Episodes 52 John James Audubon Contributors 69 List of Members 70 COPYRIGHTED 1946 BY THE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHERN FLORIDA CT. is published annually by the Historical Association of Southern Florida T 1 and the University of Miami as a -bulletinof the University. Subscrip- tion, $1.00. Communications should be addressed to the editor at the University of Miami. Neither the Association nor the University assumes responsibility for statements of fact or of opinion made by the contributors. This Page Blank in Original Source Document JANUARY, 1946 NUMBER FIVE Flagler Before Florida by SIDNEY WALTER MARTIN IN 1883 Henry Morrison Flagler made his first visit to Florida. Other visits followed and he soon realized that great possibilities lay in the State. He saw Florida as a virtual wilderness and determined to do something about it. Flagler made no vain boasts about what he would do, but soon he began to channel money into the State, and before his death in 1913 he had spent nearly $50,000,000 building hotels and rail- roads along the Florida East Coast.' His money had been made when he began to invest in Florida at the age of fifty-five, and though his enter- prises there were based partially on a business basis, the greatest motive behind his new venture was the desire to satisfy a personal ambition. -

George Henry Preble Papers, 1729-1926 (Bulk: 1729-1884)

GUIDE TO THE PREBLE FAMILY PAPERS AT THE NEW ENGLAND HISTORIC GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY Abstract: This collection contains documents primarily concerning Rear-Admiral George Henry Preble (1816-1885) and a few documents relating to his father, Enoch Preble (1763-1842), and his grandfather, Jedidiah Preble (1707-1784). The bulk of the collection consists of journals kept on ships upon which George H. Preble served including the US frigate United States, US frigate Macedonian, US sloop of war Warren, USS Levant, US steam sloop Narragansett, US steam gunboat Katahdin, US steam sloop Oneida, US sloop of war St. Louis, US steamer State of Georgia, and US steam sloop Pensacola. There are his research notes on the Boston Navy Yard, history of steam navigation, study of spherics and nautical astronomy, Preble family genealogy, and the history of the American flag. Collection also contains a record of ship disbursements recorded by Captain Enoch Preble and the Revolutionary War diary of Brigadier General Jedidiah Preble. Collection dates: 1775-1873 Volume: 3.83 linear feet Repository: R. Stanton Avery Special Collections Call Number: Mss 621 Copyright ©2010 by New England Historic Genealogical Society. All rights reserved. Reproductions are not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. Preble Family Papers Mss 621 HISTORICAL NOTE George Henry Preble was born in Portland, Maine, February 25, 1816, and died in Brookline, MA, March 1, 1885. He was the son of Captain Enoch4 and Sally (Cross) Preble, and great- great-grandson of Abraham1 Preble, of Scituate, Massachusetts, and York, Maine, an immigrant from Kent, England, in the year 1636. -

Civil War Manuscripts

CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS MANUSCRIPT READING ROW '•'" -"•••-' -'- J+l. MANUSCRIPT READING ROOM CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS A Guide to Collections in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress Compiled by John R. Sellers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 1986 Cover: Ulysses S. Grant Title page: Benjamin F. Butler, Montgomery C. Meigs, Joseph Hooker, and David D. Porter Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Civil War manuscripts. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: LC 42:C49 1. United States—History—Civil War, 1861-1865— Manuscripts—Catalogs. 2. United States—History— Civil War, 1861-1865—Sources—Bibliography—Catalogs. 3. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division—Catalogs. I. Sellers, John R. II. Title. Z1242.L48 1986 [E468] 016.9737 81-607105 ISBN 0-8444-0381-4 The portraits in this guide were reproduced from a photograph album in the James Wadsworth family papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. The album contains nearly 200 original photographs (numbered sequentially at the top), most of which were autographed by their subjects. The photo- graphs were collected by John Hay, an author and statesman who was Lin- coln's private secretary from 1860 to 1865. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. PREFACE To Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War was essentially a people's contest over the maintenance of a government dedi- cated to the elevation of man and the right of every citizen to an unfettered start in the race of life. President Lincoln believed that most Americans understood this, for he liked to boast that while large numbers of Army and Navy officers had resigned their commissions to take up arms against the government, not one common soldier or sailor was known to have deserted his post to fight for the Confederacy. -

Portland Daily Press: May 29,1885

PORTLAND I) A IT ,Y PRT1KK FRIDAY MORNING, MAY 2^,1885. ""“AitM^TTKKl PRICE THREE CENTS. ^{l23.^1862—«VQL^23._PORTLAND, _ SPECIAL. NOTICES. ENTERTAINMENT*. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, SUNK IN A FOG. THifi INDIANS. THE BASE BALL. NATIONAL EN CAM PH ENT. Published every day (Sundays excepted) by the OLD WORLD. more EASTERN NEW ENGLAND LEAGUE GAMES. PORTLAND PUBLISHING COMPANY, than Thirty Whites Killed by the Eastern New England League. Fall Detail* of the Official Pr#gr*m*ie. At 97 Exchange Street. Portland, Mb. A French Fishing Vessel Cut in Apuches—The Savages Scattering in PORTLANDS 6, BROCKTONS 3. Choice Sale! Address all oonunonloatlons to Small Bodies. Emperor William’s Illness More About 1200 people were on the Portland The committee on hotels reported that all Apron Twain and Sunk by Steamer grounds PORTLAND PUBLISHING CO. yesterday afternoon, and saw the home team defeat the hotels were not and that Tuscan, Ar., May 28.—A despatoh from Serious Than First Reported. city filled, ample 10 City of Rome. the Brocktons after a most was dozen Ladies’ Figured Deming says that the Indians have scattered exciting game. room left at the island and Old Orchard m The Portlands WEATHER INDICATIONS. small bands in different parts of southern opened the game in a lively man- hotels. The accommodations left will accom- 5 cents New Aprons, Mexico. More than thirty citizens are of the Commune Not to be ner, Annis sending the second ball pitched to him modate 8,000, and in families in the GIDDEFORD, Flags down to the lett field private Men Ill- 20 dozen 29.