How Important Are Diapycnal Mixing and Geothermal Heating for the Deep Circulation of the Western Mediterranean?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marine Mammals and Sea Turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas

Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas MEDITERRANEAN AND BLACK SEA BASINS Main seas, straits and gulfs in the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, together with locations mentioned in the text for the distribution of marine mammals and sea turtles Ukraine Russia SEA OF AZOV Kerch Strait Crimea Romania Georgia Slovenia France Croatia BLACK SEA Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Monaco Bosphorus LIGURIAN SEA Montenegro Strait Pelagos Sanctuary Gulf of Italy Lion ADRIATIC SEA Albania Corsica Drini Bay Spain Dardanelles Strait Greece BALEARIC SEA Turkey Sardinia Algerian- TYRRHENIAN SEA AEGEAN SEA Balearic Islands Provençal IONIAN SEA Syria Basin Strait of Sicily Cyprus Strait of Sicily Gibraltar ALBORAN SEA Hellenic Trench Lebanon Tunisia Malta LEVANTINE SEA Israel Algeria West Morocco Bank Tunisian Plateau/Gulf of SirteMEDITERRANEAN SEA Gaza Strip Jordan Suez Canal Egypt Gulf of Sirte Libya RED SEA Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas Compiled by María del Mar Otero and Michela Conigliaro The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by Compiled by María del Mar Otero IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain © IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Malaga, Spain Michela Conigliaro IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Copyright © 2012 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources With the support of Catherine Numa IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Annabelle Cuttelod IUCN Species Programme, United Kingdom Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the sources are fully acknowledged. -

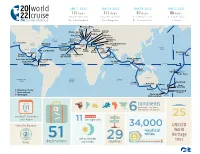

World Cruise - 2022 Use the Down Arrow from a Form Field

This document contains both information and form fields. To read information, World Cruise - 2022 use the Down Arrow from a form field. 20 world JAN 5, 2022 JAN 19, 2022 JAN 19, 2022 JAN 5, 2022 111 days 111 days 97 days 88 days 22 cruise roundtrip from roundtrip from Los Angeles to Ft. Lauderdale Ft. Lauderdale Los Angeles Ft. Lauderdale to Rome Florence/Pisa (Livorno) Genoa Rome (Civitavecchia) Catania Monte Carlo (Sicily) MONACO ITALY Naples Marseille Mykonos FRANCE GREECE Kusadasi PORTUGAL Atlantic Barcelona Heraklion Ocean SPAIN (Crete) Los Angeles Lisbon TURKEY UNITED Bermuda Ceuta Jerusalem/Bethlehem STATES (West End) (Spanish Morocco) Seville (Ashdod) ine (Cadiz) ISRAEL Athens e JORDAN Dubai Agadir (Piraeus) Aqaba Pacific MEXICO Madeira UNITED ARAB Ocean MOROCCO l Dat L (Funchal) Malta EMIRATES Ft. Lauderdale CANARY (Valletta) Suez Abu ISLANDS Canal Honolulu Huatulco Dhabi ne inn Puerto Santa Cruz Lanzarote OMAN a a Hawaii r o Hilo Vallarta NICARAGUA (Arrecife) de Tenerife Salãlah t t Kuala Lumpur I San Juan del Sur Cartagena (Port Kelang) Costa Rica COLOMBIA Sri Lanka PANAMA (Puntarenas) Equator (Colombo) Singapore Equator Panama Canal MALAYSIA INDONESIA Bali SAMOA (Benoa) AMERICAN Apia SAMOA Pago Pago AUSTRALIA South Pacific South Indian Ocean Atlantic Ocean Ocean Perth Auckland (Fremantle) Adelaide Sydney New Plymouth Burnie Picton Departure Ports Tasmania Christchurch More Ashore (Lyttelton) Overnight Fiordland NEW National Park ZEALAND up to continentscontinents (North America, South America, 111 51 Australia, Europe, Africa -

Ecosystems Mario V

Ecosystems Mario V. Balzan, Abed El Rahman Hassoun, Najet Aroua, Virginie Baldy, Magda Bou Dagher, Cristina Branquinho, Jean-Claude Dutay, Monia El Bour, Frédéric Médail, Meryem Mojtahid, et al. To cite this version: Mario V. Balzan, Abed El Rahman Hassoun, Najet Aroua, Virginie Baldy, Magda Bou Dagher, et al.. Ecosystems. Cramer W, Guiot J, Marini K. Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin -Current Situation and Risks for the Future, Union for the Mediterranean, Plan Bleu, UNEP/MAP, Marseille, France, pp.323-468, 2021, ISBN: 978-2-9577416-0-1. hal-03210122 HAL Id: hal-03210122 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03210122 Submitted on 28 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin – Current Situation and Risks for the Future First Mediterranean Assessment Report (MAR1) Chapter 4 Ecosystems Coordinating Lead Authors: Mario V. Balzan (Malta), Abed El Rahman Hassoun (Lebanon) Lead Authors: Najet Aroua (Algeria), Virginie Baldy (France), Magda Bou Dagher (Lebanon), Cristina Branquinho (Portugal), Jean-Claude Dutay (France), Monia El Bour (Tunisia), Frédéric Médail (France), Meryem Mojtahid (Morocco/France), Alejandra Morán-Ordóñez (Spain), Pier Paolo Roggero (Italy), Sergio Rossi Heras (Italy), Bertrand Schatz (France), Ioannis N. -

Wave Energy in the Balearic Sea. Evolution from a 29 Year Spectral Wave Hindcast

1 Wave energy in the Balearic Sea. Evolution from a 29 2 year spectral wave hindcast a b,∗ c 3 S. Ponce de Le´on , A. Orfila , G. Simarro a 4 UCD School of Mathematical Sciences. Dublin 4, Ireland b 5 IMEDEA (CSIC-UIB). 07190 Esporles, Spain. c 6 Institut de Ci´enciesdel Mar (CSIC). 08003 Barcelona, Spain. 7 Abstract 8 This work studies the wave energy availability in the Western Mediterranean 9 Sea using wave simulation from January 1983 to December 2011. The model 10 implemented is the WAM, forced by the ECMWF ERA-Interim wind fields. 11 The Advanced Scatterometer (ASCAT) data from MetOp satellite and the 12 TOPEX-Poseidon altimetry data are used to assess the quality of the wind 13 fields and WAM results respectively. Results from the hindcast are the 14 starting point to analyse the potentiality of obtaining wave energy around 15 the Balearic Islands Archipelago. The comparison of the 29 year hindcast 16 against wave buoys located in Western, Central and Eastern basins shows a 17 high correlation between the hindcasted and the measured significant wave 18 height (Hs), indicating a proper representation of spatial and temporal vari- 19 ability of Hs. It is found that the energy flux at the Balearic coasts range 20 from 9:1 kW=m, in the north of Menorca Island, to 2:5 kW=m in the vicinity 21 of the Bay of Palma. The energy flux is around 5 and 6 times lower in 22 summer as compared to winter. 23 Keywords: Mediterranean Sea, WAM model, wave energy, wave climate 24 variability, ASCAT, TOPEX-Poseidon ∗Corresponding author PreprintEmail submitted address: [email protected] Elsevier(A. -

THE MARINE PROTECTED AREAS of the BALEARIC SEA Marilles Foundation

THE MARINE PROTECTED AREAS OF THE BALEARIC SEA Marilles Foundation THE MARINE PROTECTED AREAS OF THE BALEARIC SEA A brief introduction What are marine protected areas? Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are portions of the marine The level of protection of the Balearic Islands’ MPAs varies environment, sometimes connected to the coast, under depending on the legal status and the corresponding some form of legal protection. MPAs are used globally as administrations. In the Balearic Islands we find MPAs in tools for the regeneration of marine ecosystems, with the inland waters that are the responsibility of the Balearic dual objective of increasing the productivity of fisheries Islands government and island governments (Consells), and resources and conserving marine habitats and species. in external waters that depend on the Spanish government. Inland waters are those that remain within the polygon We define MPAs as those where industrial or semi-indus- marked by the drawing of straight lines between the capes trial fisheries (trawling, purse seining and surface longlining) of each island. External waters are those outside. are prohibited or severely regulated, and where artisanal and recreational fisheries are subject to regulation. Figure 1. Map of the Balearic Islands showing the location of the marine protection designations. In this study we consider all of them as marine protected areas except for the Natura 2000 Network and Biosphere Reserve areas. Note: the geographical areas of some protection designations overlap. THE MARINE PROTECTED AREAS OF THE BALEARIC SEA Marilles Foundation Table 1. Description of the different marine protected areas of the Balearic Islands and their fishing restrictions. -

SESSION I : Geographical Names and Sea Names

The 14th International Seminar on Sea Names Geography, Sea Names, and Undersea Feature Names Types of the International Standardization of Sea Names: Some Clues for the Name East Sea* Sungjae Choo (Associate Professor, Department of Geography, Kyung-Hee University Seoul 130-701, KOREA E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract : This study aims to categorize and analyze internationally standardized sea names based on their origins. Especially noting the cases of sea names using country names and dual naming of seas, it draws some implications for complementing logics for the name East Sea. Of the 110 names for 98 bodies of water listed in the book titled Limits of Oceans and Seas, the most prevalent cases are named after adjacent geographical features; followed by commemorative names after persons, directions, and characteristics of seas. These international practices of naming seas are contrary to Japan's argument for the principle of using the name of archipelago or peninsula. There are several cases of using a single name of country in naming a sea bordering more than two countries, with no serious disputes. This implies that a specific focus should be given to peculiar situation that the name East Sea contains, rather than the negative side of using single country name. In order to strengthen the logic for justifying dual naming, it is suggested, an appropriate reference should be made to the three newly adopted cases of dual names, in the respects of the history of the surrounding region and the names, people's perception, power structure of the relevant countries, and the process of the standardization of dual names. -

Zooplankton Communities Fluctuations from 1995 to 2005 in the Bay of Villefranche-Sur-Mer (Northern Ligurian Sea, France)

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Biogeosciences Discuss., 7, 9175–9207, 2010 Biogeosciences www.biogeosciences-discuss.net/7/9175/2010/ Discussions doi:10.5194/bgd-7-9175-2010 © Author(s) 2010. CC Attribution 3.0 License. This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Biogeosciences (BG). Please refer to the corresponding final paper in BG if available. Zooplankton communities fluctuations from 1995 to 2005 in the Bay of Villefranche-sur-Mer (Northern Ligurian Sea, France) P. Vandromme1,2, L. Stemmann1,2, L. Berline1,2, S. Gasparini1,2, L. Mousseau1,2, F. Prejger1,2, O. Passafiume1,2, J.-M. Guarini3,4, and G. Gorsky1,2 1UPMC Univ. Paris 06, UMR 7093, LOV, Observatoire oceanologique,´ 06234, Villefranche/mer, France 2CNRS, UMR 7093, LOV, Observatoire oceanologique,´ 06234, Villefranche/mer, France 3UPMC Univ. Paris 06, Oceanographie,´ Environnements Marins, 4 Place Jussieu, 75005 Paris 4CNRS, INstitute Environment Ecology, INEE, 3 Rue Michel-Ange, 75016 Paris 9175 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Received: 8 November 2010 – Accepted: 18 November 2010 – Published: 15 December 2010 Correspondence to: L. Stemmann ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. 9176 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract An integrated analysis of the pelagic ecosystems of the Ligurian Sea is performed com- bining time series of different zooplankton groups (small and large copepods, chaetog- naths, appendicularians, pteropods, thaliaceans, decapods larvae, other crustaceans, 5 other gelatinous and other zooplankton), chlorophyll-a and nutrients, seawater salinity, temperature and density and local weather at the Point B coastal station (Northern Lig- urian Sea). -

SEISMIC REFRACTION MEASUREMENTS in the WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN SEA by DAVIS ARMSTRONG FAHLQUIST BS, Brown University

0 ~I~i7 SEISMIC REFRACTION MEASUREMENTS IN THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN SEA by DAVIS ARMSTRONG FAHLQUIST B. S., Brown University (1950) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1963 Signature of Author Department of Geoogy and Geophysics Certified by 2%Kes~i Supervisor Accepted by Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students 2 38 ABSTRACT SEISMIC REFRACTION MEASUREMENTS IN THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN SEA by Davis Armstrong Fahlquist Submitted to the Department of Geology and Geophysics on 4 February, 1963, in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Results of seismic refraction studies conducted from the research vessels ATLANTIS and CHAIN (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution), WINNARETTA SINGER (Musee Oceanographique de Monaco), and VEMA (Lamont Geological Observatory) are presented. Depths to the Mohorovicic discontinuity vary from 11 to 14 km. at four refraction stations located in the deep water area bounded by the Balearic Islands, Corsica, and southern France; the mantle veloci- ties measured at these stations vary from 7. 7 to 8. 0 km/sec. Over- lying the high velocity material at three of these stations is a layer of material having a velocity of 6. 5 to 6. 8 km/sec and varying in thickness from 2 to 3 km. A significantly lower velocity, 6. 0 km/ sec, was measured for the layer directly overlying the mantle on the profile extending from near Cape Antibes to Corsica. All profiles in the northern part of the western Mediterranean Basin show the pres- ence of a 4 to 6 km. -

Central Water Masses Variability in the Southern Bay of Biscay from Early 90'S. the Effect of the Severe Winter 2005. ICES C

ICES CM 2006/C:26 ICES Annual Science Conference. Maastricht. September 2006 NOT TO BE CITED WITHOUT PREVIOUS NOTICE TO AUTHORS Central water masses variability in the southern Bay of Biscay from early 90's. The e®ect of the severe winter 2005 C¶esarGonz¶alez-Pola*y, Alicia Lav¶³nz, Raquel Somavillaz and Manuel Vargas-Y¶a~nezx Instituto Espa~nolde Oceanograf¶³a y C.O. de Gij¶on, z C.O. de Santander, x C.O. de M¶alaga * Avda Pr¶³ncipe de Asturias 70, 33212 Gij¶on,Spain, [email protected] Abstract A monthly hydrographical time series carried out by the Spanish Institute of Oceanography in the southern Bay of Biscay (eastern North Atlantic), covering the upper 1000 m, have shown local warming rates for the last 10-15 years that are much higher than the long-term ocean trend in the 20th century. At Mediterranean Water (MW) level this warming is linked to an e®ective modi¯cation of the termohaline properties but at the East North Atlantic Central Water (ENACW) levels the warming was mainly related to isopycnal sinking (heave) until winter 2005. The overall picture is consistent with the fact that climatic warming has accelerated over the last few decades. The anomalous winter of 2005 in south-western Europe (extremely cold and dry) caused the lowest temperature record of the time-series 1993-2005 for the surface waters in the southern Bay of Biscay, and the mixed layer reached unprecedented depths greater than 300 m. The isopycnal level σθ = 27:1 classically used to analyze ENACW variability disappeared (outcrops further south) and as a result the hydrographical structure of the upper layers of the ENACW was strongly modi¯ed remaining in summer 2006 completely di®erent than what it was in the previous decade. -

DUACS DT2018: 25 Years of Reprocessed Sea Level Altimetry Products

Ocean Sci., 15, 1207–1224, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/os-15-1207-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. DUACS DT2018: 25 years of reprocessed sea level altimetry products Guillaume Taburet1, Antonio Sanchez-Roman2, Maxime Ballarotta1, Marie-Isabelle Pujol1, Jean-François Legeais1, Florent Fournier1, Yannice Faugere1, and Gerald Dibarboure3 1Collecte Localisation Satellites, Parc Technologique du Canal, 8–10 rue Hermès, 31520 Ramonville-Saint-Agne, France 2Instituto Mediterráneo de Estudios Avanzados, C/Miquel Marquès, 21, 07190 Esporles, Illes Balears, Spain 3Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales, 18 avenue Edouard Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France Correspondence: Guillaume Taburet ([email protected]) Received: 19 December 2018 – Discussion started: 8 January 2019 Revised: 28 May 2019 – Accepted: 16 July 2019 – Published: 12 September 2019 Abstract. For more than 20 years, the multi-satellite Data 1 Introduction Unification and Altimeter Combination System (DUACS) has been providing near-real-time (NRT) and delayed- Since 1992, high-precision sea level measurements have time (DT) altimetry products. DUACS datasets range been provided by satellite altimetry. They have largely con- from along-track measurements to multi-mission sea level tributed to abetter understanding of both the ocean circula- anomaly (SLA) and absolute dynamic topography (ADT) tion and the response of the Earth’s system to climate change. maps. The DUACS DT2018 ensemble of products is the most Following TOPEX–Poseidon in 1992, the constellation has recent and major release. For this, 25 years of altimeter data grown from one to six satellites flying simultaneously (see have been reprocessed and are available through the Coperni- Fig. -

Watercraft, People, and Animals: Setting the Stage for the Neolithic Colonization of the Mediterranean Islands of Cyprus and Crete

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2015 Watercraft, People, and Animals: Setting the Stage for the Neolithic Colonization of the Mediterranean Islands of Cyprus and Crete Katelyn Dibenedetto University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Repository Citation Dibenedetto, Katelyn, "Watercraft, People, and Animals: Setting the Stage for the Neolithic Colonization of the Mediterranean Islands of Cyprus and Crete" (2015). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2346. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/7645879 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WATERCRAFT, PEOPLE, AND ANIMALS: SETTING THE STAGE FOR THE NEOLITHIC COLONIZATION OF THE MEDITERRANEAN ISLANDS OF CYPRUS AND CRETE By Katelyn DiBenedetto Bachelor -

Crossing the Line: Migratory and Homing Behaviors of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna

Vol. 504: 265–276, 2014 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published May 14 doi: 10.3354/meps10781 Mar Ecol Prog Ser FREEREE ACCESSCCESS Crossing the line: migratory and homing behaviors of Atlantic bluefin tuna Jay R. Rooker1,*, Haritz Arrizabalaga2, Igaratza Fraile2, David H. Secor3, David L. Dettman4, Noureddine Abid5, Piero Addis6, Simeon Deguara7, F. Saadet Karakulak8, Ai Kimoto9, Osamu Sakai9, David Macías10, Miguel Neves Santos11 1Department of Marine Biology, Texas A&M University, 1001 Texas Clipper Road, Galveston, Texas 77553 USA 2AZTI Tecnalia, Marine Research Division, Herrea Kaia, Portualdea z/g 20110 Pasaia, Gipuzkoa, Spain 3Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, PO Box 38, Solomons, Maryland 20688, USA 4Environmental Isotope Laboratory, Department of Geosciences, 1040 E. 4th Street, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA 5Institut National de la Recherche Halieutique, INRH, Regional Centre of Tangier, BP: 5268, Dradeb, Tangier, Morocco 6Department of Life Science and Environment, University of Cagliari, Via Fiorelli 1, 09126 Cagliari, Italy 7Federation of Maltese Aquaculture Producers 54, St. Christopher Str., Valletta VLT 1462, Malta 8Faculty of Fisheries, Istanbul University, Ordu Cad. N° 200, 34470 Laleli, Istanbul, Turkey 9National Research Institute of Far Seas Fisheries, 5-7-1 Orido Shimizu, Shizuoka, Japan 10Spanish Institute of Oceanography, Corazón de María 8, 28002 Madrid, Spain 11Instituto Nacional dos Recursos Biológicos (INRB I.P. IPIMAR), Avenida 5 de Outubro s/n, 8700-305 Olhao, Portugal ABSTRACT: Assessment and management of Atlantic bluefin tuna Thunnus thynnus populations is hindered by our lack of knowledge regarding trans-Atlantic movement and connectivity of east- ern and western populations. Here, we evaluated migratory and homing behaviors of bluefin tuna in several regions of the North Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea using chemical tags (δ13C and δ18O) in otoliths.