ELECTRYONE ΗΛΕΚΤΡΥΩΝΗ the Earliest Communication System In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

Table of Contents 1

Maria Hnaraki, 1 Ph.D. Mentor & Cultural Advisor Drexel University (Philadelphia-U.S.A.) Associate Teaching Professor Official Representative of the World Council of Cretans Kids Love Greece Scientific & Educational Consultant Tel: (+) 30-6932-050-446 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Table of Contents 1. FORMAL EDUCATION ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. ADDITIONAL EDUCATION .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 3. EMPLOYMENT RECORD ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 3.1. Current Status (2015-…) ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 3.2. Employment History ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 3.2.1. Teaching Experience ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 3.2.2. Research Projects .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Print This Article

Byzantina Symmeikta Vol. 29, 2019 Byzantine families in Venetian context: The Gavalas and Ialinas family in Venetian Crete (XIIIth- XIVth centuries) ΓΑΣΠΑΡΗΣ Χαράλαμπος Institute of Historical Research, Athens https://doi.org/10.12681/byzsym.16249 Copyright © 2019 Χαράλαμπος Γάσπαρης To cite this article: ΓΑΣΠΑΡΗΣ, (2019). Byzantine families in Venetian context: The Gavalas and Ialinas family in Venetian Crete (XIIIth- XIVth centuries). Byzantina Symmeikta, 29, 1-132. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/byzsym.16249 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 30/09/2021 15:19:54 | INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH ΙΝΣΤΙΤΟΥΤΟ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΚΩΝ ΕΡΕΥΝΩΝ SECTION OF BYZANTINE RESEARCH ΤΟΜΕΑΣ ΒΥΖΑΝΤΙΝΩΝ ΕΡΕΥΝΩΝ NATIONAL HELLENIC RESEARCH FOUNDATION ΕΘΝΙΚΟ IΔΡΥΜΑ ΕΡΕΥΝΩΝ CHARALAMBOS GASPARIS EFI RAGIA Byzantine Families in Venetian Context: THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE PROVINCIAL ADMINISTRATION OF THE TheBYZAN GavalasTINE E andMPI REIalinas (CA 600-1200):Families I.1.in T HVenetianE APOTHE CreteKAI OF (XIIIth–XIVthASIA MINOR (7T HCenturies)-8TH C.) ΤΟΜΟΣ 29 VOLUME ΠΑΡΑΡΤΗΜΑ / APPENDIX ΑΘΗΝΑ • 20092019 • ATHENS http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 30/09/2021 15:19:54 | http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 30/09/2021 15:19:54 | http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 30/09/2021 15:19:54 | ΒΥΖΑΝΤΙΝΑ ΣΥΜΜΕΙΚΤΑ 29 ΠΑΡΑΡΤΗΜΑ ΒΥΖΑΝΤΙΝΑ SYMMEIKTA 29 APPENDIX http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 30/09/2021 15:19:54 | NATIONAL HELLENIC RESEARCH FOUNDATION INSTITUTE OF -

Antonis ANASTASOPOULOS

Antonis ANASTASOPOULOS Date of birth 11 December 1969 Nationality Greek Contact details Department of History and Archaeology, University of Crete, (work) 74100 Rethymno, Greece Tel: (+30)2831077368/2831077337, fax: (+30)2831077338 Contact details P.O. Box 561, 74102 Rethymno, Greece (home) Tel.: (+30)2831055774 email: anastasopoulos[at]uoc.gr Personal website www.antonisanastasopoulos.gr Education 1994-1999 Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Cambridge Ph.D. ‘Imperial Institutions and Local Communities: Ottoman Karaferye, 1758-1774’ (supervisor: Prof. İ. Metin Kunt) Outline: Study of centre-periphery relations, provincial administration and elite in the region of Veroia (Karaferye) in 1758-1774 through the use of Ottoman archival sources. Grants/studentships: 1994-1997: British Academy Fees Only Studentship, A.G. Leventis Foundation Educational Grant, Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation Scholarship, Peterhouse Research Studentship; 1995-1996: Martin Hinds Travel Grants, Worts Travelling Scholars Grant, Peterhouse Grants for Research Purposes, Skilliter Centre for Ottoman Studies Grant. 1993-1994 Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Cambridge M.Phil. (Islamic Studies). Thesis: ‘The Judicial System in Ottoman Greece, 1600-1800’ (supervisor: Prof. İ. Metin Kunt) Outline: The Ottoman ideal of justice and a study of Islamic, Christian, and Jewish courts of law in Ottoman Greece during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. [July 1992-July 1993 & March-September 1998 Military service.] 1987-1992 Department of History and Archaeology, University of Athens Degree in History and Archaeology, specialisation in History. [Spring semester 1990: ERASMUS-ECTS exchange student in History; Roskilde University, Denmark (supervisor: Prof. Nils Hybel).] Teaching & research experience I have been teaching Ottoman History at the Department of History and Archaeology of the University of Crete (Greece) at undergraduate and postgraduate levels since February 1999 and February 2001, respectively. -

Visa & Residence Permit Guide for Students

Ministry of Interior & Administrative Reconstruction Ministry of Foreign Affairs Directorate General for Citizenship & C GEN. DIRECTORATE FOR EUROPEAN AFFAIRS Immigration Policy C4 Directorate Justice, Home Affairs & Directorate for Immigration Policy Schengen Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.ypes.gr www.mfa.gr Visa & Residence Permit guide for students 1 Index 1. EU/EEA Nationals 2. Non EU/EEA Nationals 2.a Mobility of Non EU/EEA Students - Moving between EU countries during my short-term visit – less than three months - Moving between EU countries during my long-term stay – more than three months 2.b Short courses in Greek Universities, not exceeding three months. 2.c Admission for studies in Greek Universities or for participation in exchange programs, under bilateral agreements or in projects funded by the European Union i.e “ERASMUS + (placement)” program for long-term stay (more than three months). - Studies in Greek universities (undergraduate, master and doctoral level - Participation in exchange programs, under interstate agreements, in cooperation projects funded by the European Union including «ERASMUS+ placement program» 3. Refusal of a National Visa (type D)/Rights of the applicant. 4. Right to appeal against the decision of the Consular Authority 5. Annex I - Application form for National Visa (sample) Annex II - Application form for Residence Permit Annex III - Refusal Form Annex IV - Photo specifications for a national visa application Annex V - Aliens and Immigration Departments Contacts 2 1. Students EU/EEA Nationals You will not require a visa for studies to enter Greece if you possess a valid passport from an EU Member State, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway or Switzerland. -

The Seascape in Aegean Prehistory

The seascape in Aegean Prehistory Edited by Giorgos Vavouranakis Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens Volume 14 The seascape in Aegean Prehistory Edited by Giorgos Vavouranakis Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens Volume 14 3 To Matti Egon, – a distinguished representative of Greek maritime culture 5 © Copyright The Danish Institute at Athens, Athens 2011 The seascape in Aegean Prehistory Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens Volume 14 General Editor: Erik Hallager Graphic design: Erik Hallager Printed at Narayana Press Printed in Denmark on permanent paper conforming to ANSI Z 39.48-1992 The publication was sponsored by: Institute for Aegean Prehistory Cypriot Ministry of Education and Culture Matti Egon The Psycha Foundation Konsul Georg Jorck og hustru Emma Jorck’s Fond ISBN: 978-87-7934-571-3 Distributed by: AARHUS UNIVERSITY PRESS Langelandsgade 177 DK-8200 Århus N www.unipress.dk Gazelle Book Services Ltd. White Cross Mills, Hightown Lancaster LA1 4XS, England www.gazellebooks.com The David Brown Book Company (DBBC) P.O. Box 511 Oakville, CT. 06779, USA www.davidbrownbookco.uk Front cover: Motif from lost Mochlos ring Drawing G. Vavouranakis with the assistance of G. Manginis 6 Contents 9 List of contributors 11 Preface Giorgos Vavouranakis 13 Introduction Giorgos Vavouranakis 31 The paradox of early voyaging in the Mediterranean and the slowness of the Neolithic transition between Cyprus and Italy Albert J. Ammerman 51 Fishing (in) Aegean seascapes: early Aegean fishermen and their world Tatiana Theodoropoulou 71 Further thoughts on the International Spirit: maritime politics and consuming bodies in the early Cyclades Despina Catapoti 91 Funerary customs and martime activity in Early Bronze Crete Giorgos Vavouranakis 119 Towards a conceptualisation of the sea: artefacts, iconography and meaning Ina Berg 139 Fish and ships: Neopalatial seascapes in context Matthew Haysom 161 A view from the sea John G. -

HOTELS | PROGRAMS | ISLAND HOPPING | TOURS | CRUISES | CAR RENTAL | YACHT CHARTER | TURKEY EXTENSIONS Meteora

GREECE 2020 HOTELS | PROGRAMS | ISLAND HOPPING | TOURS | CRUISES | CAR RENTAL | YACHT CHARTER | TURKEY EXTENSIONS Meteora 2 GREECE 2020 • GREECE AND MEDITERRANEAN TRAVEL CENTRE Welcome to Greece As my second home and where Greece and Mediterranean Travel Centre began, Greece holds a special place in my heart. Its hidden gems are still exciting for me to share and I love being able to offer the Halina Kubica traditional Greece, known only to locals, Owner & Managing Director as well as the popular ancient treasures Greece is renowned for. It always surprises travellers when they discover there are 227 idyllic inhabited islands, stunning ruins, and mountainous mainland to explore of unique beauty and rare customs. Sampling freshly cooked local food at the small taverna with the stunning backdrop of the Aegean Sea is the highlight of each of my trips and I hope will be yours too. Let us show you Greece like you’ve never imagined, so you can experience a little piece of our home. GREECE 2020 • GREECE AND MEDITERRANEAN TRAVEL CENTRE 3 Let us take you on the Trip of a Lifetime Greece and Mediterranean Travel Centre is your local boutique Australian owned and operated company. We have been designing holidays with the Australian traveller in mind for over 17 years. With personal, hands-on service, you can rest assured that your holiday will be impeccable from start to finish. Travel with us and experience the difference... Athens Zakynthos 4 GREECE 2020 • GREECE AND MEDITERRANEAN TRAVEL CENTRE Santorini Expert Knowledge Trusted Security We are destination experts of Greece and the Mediterranean. -

British Aid to Greece, 1940-1941

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Military History History 1986 Diary of a Disaster: British Aid to Greece, 1940-1941 Robin Higham Kansas State University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Higham, Robin, "Diary of a Disaster: British Aid to Greece, 1940-1941" (1986). Military History. 9. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_military_history/9 Diary of a Disaster o Moscow ° Berlino ATLANTIC OCEAN °Ankara Malta ~Athe~ns ALGERIA MEDITERRANEAN SEAc/ Benghazi . Cairo i I I I I I I SUDAN I I Khartoum )J ...\~ .Jl~N£Q!!E~ENT ROUTE ,/ ~- ""'------- ~--_/ ~ / / / / EAST AFRICA I I 1000 MILE RADIUS FROM LONDON AND CAIRO Diary of a Disaster British Aid to Greece 1940-1941 ROBIN HIGHAM THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY For Barbara for thirty-six years of love and friendship Copyright © 1986 by Robin Higham Published by the University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2009 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. -

AEGEAN FEASTI NG Pages 247-279 a MINOAN PERSPECTIVE

HESPERIA 73 (2004) AEGEAN FEASTI NG Pages 247-279 A MINOAN PERSPECTIVE ABSTRACT This survey of feasting in Bronze Age Crete reveals that feasts could be ei- ther exclusiveelite celebrationsor unrestrictedoccasions in which socialiden- tity ratherthan powerwas most important. In contrast,Mycenaean feasting on the Greek mainlandseems to have arisenfrom elite customs aimed at ex- clusion. A comparison of the evidence for Late Minoan IIIC feasting at Phaistos and convivialpractices on the mainland indicates new Mycenaean components to Cretanfeasting, suggesting that the earlierpattern had shifted and that Cretanfeasts had similarlybecome elite instrumentsof competition and negotiation for authority. The purpose of this article is to investigate the archaeologicalevidence for convivial practices in Bronze Age Crete and to compare it with the mate- rial indications of feasting on the mainland of Greece.' Through compari- son of Mycenaean evidence and two large LM IIIB-C pottery assem- blages at Phaistos, I point out discrepancies as well as reciprocalcontribu- tions in traditions of Minoan and Mycenaean feasting. I suggest that the evidence from Phaistos demonstrates that communal drinking and feasts in LM IIIB-C Crete were celebrated to facilitate social communication and promote ideological strategies and political activities. In the following study,I take into account the role that pottery plays in the investigation and recognition of social patterns in feasting. In ceramic 1. I would like to thank Sharon and the Hesperiareferees, Brian Hay- Italian excavationsat Ayia Triadaand Stocker andJames Wright for inviting den and JeremyRutter, who drew my Phaistos,who involved me in the study me to participatein the colloquiumon attention to importantpoints. -

18-05-21 Acts Against Religious Sites in Greece

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND RELIGIOUS AFFAIRS GENERAL SECRETARIAT FOR RELIGIOUS AFFAIRS DIRECTORATE FOR RELIGIOUS EDUCATION AND INTERFAITH RELATIONS DEPARTMENT FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOMS AND INTERFAITH RELATIONS ACTS AGAINST RELIGIOUS SITES IN GREECE REPORT 2019 All maps and statistical analysis are also available, in Greek and in English, on the website: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/458d92cb4558471bb59b78f2597b596c Cover page: Geographical display of all incidents presented in the 2019 Report. Original map-layout source: Hellenic Statistical Authority Back cover: Detail of inscription, Holy Monastery of St. George Hozeva, Israel All maps (except for II.A.2.c.iii) as well as statistical processing and data presentation were prepared, upon request and instructions by the General Secretariat for Religious Affairs, by V. Rev. Archimandrite Ioannis-Georgios Peristerides, Chemical Engineer MSc, Theologian MA, PhD candidate of School of Rural and Surveying Engineering, National Technical University of Athens- whom we warmly thank - with the support of the research group “GeoCHOROS” of the National Technical University of Athens and were granted free of charge. Copyright ©2020 General Secretariat for Religious Affairs, Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ The Report (in Greek and in English) is available online on the website of the Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs: www.minedu.gov.gr COURTESY AND NON-OFFICIAL TRANSLATION Content enriched Translated and adapted by Callis MITRAKA 2 “I have loved, O Lord, the beauty of thy house; and the place where thy glory dwelleth” (Psalm, 25:8) . ָשְְ ֵּבב הן ָכ תשמ ,ם ָןְְּו ; ֶָךה ֵּיב ָןעְמ ,י תי ְָ הַה--הָיהְי ( ים הִּ הְִּת ח) “Domine dilexi decorem domus tuae et locum habitationis gloriae tuae” (Ps. -

Sgei Report for the Year 2018 in Accordance with the 2012 Sgei Decision and in Accordance with the Sgei Framework 2012 Overview of Expenditure

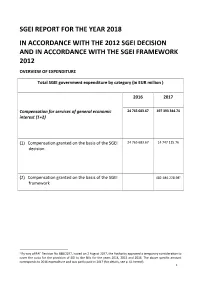

SGEI REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2018 IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE 2012 SGEI DECISION AND IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE SGEI FRAMEWORK 2012 OVERVIEW OF EXPENDITURE Total SGEI government expenditure by category (in EUR million ) 2016 2017 Compensation for services of general economic 24 765 683.67 497 393 344.74 interest (1+2) (1) Compensation granted on the basis of the SGEI 24 765 683.67 14 747 115.76 decision (2) Compensation granted on the basis of the SGEI 482 646 228.981 framework 1 By way of RAE Decision No 688/2017, issued on 2 August 2017, the Authority approved a temporary consideration to cover the costs for the provision of SGI to the NIIs for the years 2014, 2015 and 2016. The above specific amount corresponds to 2016 expenditure and was partly paid in 2017 (for details, see p. 61 hereof). 1 I. APPLICATION OF THE 2012 SGEI DECISION 1. SOCIAL SGEI Clear and comprehensive description of how the respective services are organized in your Member State. Explanation of what kind of services in the respective sector have been defined as SGEI in your Member State. Please list the contents of the services entrusted as SGEIs as clearly as possible. Services designated as social SGEIs fall into two categories: (A) Provision and operation of structures to tackle poverty in various municipalities in the country. These structures include the following: - Social Pharmacy; - Social Grocery Stores; - Social Meals Scheme; - Mediation Office; - Time Exchange; - Homeless Day Reception Centre; - Homeless Hostel. Through the operation of the above structures, psychosocial support and information services are also provided for the empowerment and social integration of the beneficiaries. -

Lasithi: a History of Settlement on a Highland Plain in Crete

HESPERIA: SUPPLEMENT XVIII LASITHI A HISTORY OF SETTLEMENT ON A HIGHLAND PLAIN IN CRETE Athens at Studies CC-BY-NC-ND. License: Classical of only. BY use School LIVINGSTON VANCE WATROUS personal American © For AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1982 This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.61 on Tue, 4 Dec 2012 14:50:06 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions PUBLISHEDWITH THE AID OF A GRANT FROM THE JULIANPARK PUBLICATIONFUND THE STATEUNIVERSITY OF NEW YORKAT BUFFALO Athens at Studies CC-BY-NC-ND. License: Classical of only. use School Libraryof CongressCataloging in PublicationData Watrous,Livingston Vance, 1943- personal Lasithi,a historyof settlement on a highland American plainin Crete. © For (Hesperia:Supplement ; 18) Bibliography:p. ix-xiii Includesindex. 1. Lasithi,Greece-Antiquities. 2. Excavations (Archaeology)-Greece, Modern-Lasithi. 3. Lasithi, Greece-History. 4. Greece, Modern-Antiquities. I. Title. II. Series:Hesperia, journal of the AmericanSchool of ClassicalStudies at Athens : Sup- plement ; 18. DF221.C8W37 939'.18 80-26460 ISBN0-87661-518-3 This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.61 on Tue, 4 Dec 2012 14:50:06 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Athens at This content downloaded by theauthorized user from192.168.52.61 on Tue,4 Dec 201214:50:06 PM Studies CC-BY-NC-ND. Ei ro v All usesubject to License: kaov Classical of and for Harriet for and 'AYLoV only. JSTOR Terms andConditions FEcopylov, use School AaoaaOov personal American © For PREFACE It is a pleasure to acknowledge the help and advice which have made this study possible.