Excavations in the Hagios Charalambos Cave

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dual Naming of Sea Areas in Modern Atlases and Implications for the East Sea/Sea of Japan Case

Dual naming of sea areas in modern atlases and implications for the East Sea/Sea of Japan case Rainer DORMELS* Dual naming is, to varying extents, present in nearly all atlases. The empirical research in this paper deals with the dual naming of sea areas in about 20 atlases from different nations in the years from 2006 to 2017. Objective, quality, and size of the atlases and the country where the atlases originated from play a key role. All these characteristics of the atlases will be taken into account in the paper. In the cases of dual naming of sea areas, we can, in general, differentiate between: cases where both names are exonyms, cases where both names are endonyms, and cases where one name is an endonym, while the other is an exonym. The goal of this paper is to suggest a typology of dual names of sea areas in different atlases. As it turns out, dual names of sea areas in atlases have different functions, and in many atlases, dual naming is not a singular exception. Dual naming may help the users of atlases to orientate themselves better. Additionally, dual naming allows for providing valuable information to the users. Regarding the naming of the sea between Korea and Japan present study has achieved the following results: the East Sea/Sea of Japan is the sea area, which by far showed the most use of dual naming in the atlases examined, in all cases of dual naming two exonyms were used, even in atlases, which allow dual naming just in very few cases, the East Sea/Sea of Japan is presented with dual naming. -

Verification of Vulnerable Zones Identified Under the Nitrate Directive \ and Sensitive Areas Identified Under the Urban Waste W

CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 THE URBAN WASTEWATER TREATMENT DIRECTIVE (91/271/EEC) 1 1.2 THE NITRATES DIRECTIVE (91/676/EEC) 3 1.3 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 4 2 THE OFFICIAL GREEK DESIGNATION PROCESS 9 2.1 OVERVIEW OF THE CURRENT SITUATION IN GREECE 9 2.2 OFFICIAL DESIGNATION OF SENSITIVE AREAS 10 2.3 OFFICIAL DESIGNATION OF VULNERABLE ZONES 14 1 INTRODUCTION This report is a review of the areas designated as Sensitive Areas in conformity with the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive 91/271/EEC and Vulnerable Zones in conformity with the Nitrates Directive 91/676/EEC in Greece. The review also includes suggestions for further areas that should be designated within the scope of these two Directives. Although the two Directives have different objectives, the areas designated as sensitive or vulnerable are reviewed simultaneously because of the similarities in the designation process. The investigations will focus upon: • Checking that those waters that should be identified according to either Directive have been; • in the case of the Nitrates Directive, assessing whether vulnerable zones have been designated correctly and comprehensively. The identification of vulnerable zones and sensitive areas in relation to the Nitrates Directive and Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive is carried out according to both common and specific criteria, as these are specified in the two Directives. 1.1 THE URBAN WASTEWATER TREATMENT DIRECTIVE (91/271/EEC) The Directive concerns the collection, treatment and discharge of urban wastewater as well as biodegradable wastewater from certain industrial sectors. The designation of sensitive areas is required by the Directive since, depending on the sensitivity of the receptor, treatment of a different level is necessary prior to discharge. -

Marine Turtle Research and Conservation in Libya

Marine TurTle research and conservaTion in libya a conTribuTion To safeguarding MediTerranean biodiversiTy legal notice: The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Specially Protected Areas Regional Activity Centre (SPA/RAC) and United Nations Environment Programme / Mediterranean Action Plan (UNEP/MAP) concerning the legal status of any State, Territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of their frontiers or boundaries. copyright: All property rights of texts and content of different types of this publication belong to SPA/RAC. Reproduction of these texts and contents, in whole or in part, and in any form, is prohibited without prior written permission from SPA/RAC, except for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that the source is fully acknowledged. © 2021 united nations environment Programme Mediterranean action Plan specially Protected areas regional activity centre Boulevard du Leader Yasser Arafat B.P.337 - 1080 Tunis Cedex – TUNISIA [email protected] for bibliographic purposes, this volume may be cited as: SPA/RAC-UNEP/MAP, 2021. Marine Turtle Research and Conservation in Libya: A contribution to safeguarding Mediterranean Biodiversity. By Abdulmaula Hamza. Ed. SPA/RAC, Tunis: pages 77. cover photo credit: sPa/rac, artescienza copyright of the photos: libsTP The present report has been prepared in the framework of the Marine Turtles project fnanced by MAVA. For more information: www-spa-rac.org Marine Turtle Research and Conservation in Libya A contribution to safeguarding Mediterranean Biodiversity Study required and fnanced by: Specially Protected Areas Regional Activity Centre (SPA/RAC) Boulevard du Leader Yasser Arafat B.P. -

{TEXTBOOK} Missing in Action

MISSING IN ACTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Francis Bergèse | 48 pages | 09 Feb 2017 | CINEBOOK LTD | 9781849183437 | English | Ashford, United Kingdom Missing in Action () - IMDb Normalization of U. Considerable speculation and investigation has gone to a theory that a significant number of these men were captured as prisoners of war by Communist forces in the two countries and kept as live prisoners after the war's conclusion for the United States in Its unanimous conclusion found "no compelling evidence that proves that any American remains alive in captivity in Southeast Asia. This missing in action issue has been a highly emotional one to those involved, and is often considered the last depressing, divisive aftereffect of the Vietnam War. To skeptics, "live prisoners" is a conspiracy theory unsupported by motivation or evidence, and the foundation for a cottage industry of charlatans who have preyed upon the hopes of the families of the missing. As two skeptics wrote in , "The conspiracy myth surrounding the Americans who remained missing after Operation Homecoming in had evolved to baroque intricacy. By , there were thousands of zealots—who believed with cultlike fervor that hundreds of American POWs had been deliberately and callously abandoned in Indochina after the war, that there was a vast conspiracy within the armed forces and the executive branch—spanning five administrations—to cover up all evidence of this betrayal, and that the governments of Communist Vietnam and Laos continued to hold an unspecified number of living American POWs, despite their adamant denials of this charge. It is only hard evidence of a national disgrace: American prisoners were left behind at the end of the Vietnam War. -

Stomatopoda of Greece: an Annotated Checklist

Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e47183 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.8.e47183 Taxonomic Paper Stomatopoda of Greece: an annotated checklist Panayota Koulouri‡, Vasilis Gerovasileiou‡§, Nicolas Bailly , Costas Dounas‡ ‡ Hellenic Center for Marine Recearch (HCMR), Heraklion, Greece § WorldFish Center, Los Baños, Philippines Corresponding author: Panayota Koulouri ([email protected]) Academic editor: Eva Chatzinikolaou Received: 09 Oct 2019 | Accepted: 15 Mar 2020 | Published: 26 Mar 2020 Citation: Koulouri P, Gerovasileiou V, Bailly N, Dounas C (2020) Stomatopoda of Greece: an annotated checklist. Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e47183. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.8.e47183 Abstract Background The checklist of Stomatopoda of Greece was developed in the framework of the LifeWatchGreece Research Infrastructure (ESFRI) project, coordinated by the Institute of Marine Biology, Biotechnology and Aquaculture (IMBBC) of the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research (HCMR). The application of the Greek Taxon Information System (GTIS) of this project has been used in order to develop a complete checklist of species recorded from the Greek Seas. The objectives of the present study were to update and cross-check all the stomatopod species that are known to occur in the Greek Seas. Inaccuracies and omissions were also investigated, according to literature and current taxonomic status. New information The up-to-date checklist of Stomatopoda of Greece comprises nine species, classified to eight genera and three families. Keywords Stomatopoda, Greece, Aegean Sea, Sea of Crete, Ionian Sea, Eastern Mediterranean, checklist © Koulouri P et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

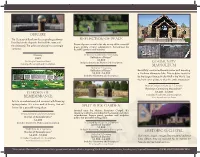

REFLECTION of PEACE Lined by Blocks of Granite That Hold the Names of Doves of Peace Reach to the Sky on Top of the Emerald the Deceased

OSSUARY The Ossuary at Roselawn has a spiraling pathway REFLECTION OF PEACE lined by blocks of granite that hold the names of Doves of peace reach to the sky on top of the emerald the deceased. The ashes are placed in a co-mingle green granite circular columbarium. Surrounded by container. beautiful gardens and benches. Ossuary In Ground Burial Lots for 2 Cremains $895 Reflection of Peace* Co-Mingle Cremation Burial $3,800 Includes Interment, Marker and Inscription COMMUNITY Includes Placement and Inscription MAUSOLEUM Niche for 2 Cremains Reflection of Peace* Beautifully constructed bronze niche wall depicting $3,600 - $4,200 a Northern Minnesota Lake. This sculpture is said to Includes Placement and Inscription be the Largest Bronze Niche Wall in the World. See the front cover picture to view the entire mausoleum. Bronze Cremation Niche for 2 Cremains Roselawn Community Mausoleum* GARDEN OF $6,400 - $6,800 Includes Placement and Inscription REMEMBRANCE Price depends on row chosen Set into an embankment and accented with flowering topiary planters. It is a true work of beauty. And will SPLIT ROCK GARDEN forever be a peaceful resting place. Located near the Historic Roselawn Chapel, this In Ground Burial Lots for 2 Cremains limestone wall is the backdrop for the newest cremation columbarium. Serene pond, gardens and sculpture Garden of Remembrance* add to the peaceful resting place. $4,600 Includes Interment, Marker and Inscription In Ground Burial Lots for 2 Cremains Split Rock Garden* $3,800 Wall Niche for 2 Cremains Includes Interment, Marker and Inscription Garden of Remembrance* HISTORICAL CHAPEL $4,400 - $5,000 Niche for 2 Cremains Split Rock Garden* Our historic chapel, designed by renowned architect Includes Placement and Inscription $3,800 - $4,400 Cass Gilbert, may be reserved by lot owners for Price depends on row chosen Includes Placement and Inscription funerals and memorial services. -

This Pdf Is a Digital Offprint of Your Contribution in E. Alram-Stern, F

This pdf is a digital offprint of your contribution in E. Alram-Stern, F. Blakolmer, S. Deger-Jalkotzy, R. Laffineur & J. Weilhartner (eds), Metaphysis. Ritual, Myth and Symbolism in the Aegean Bronze Age (Aegaeum 39), ISBN 978-90-429-3366-8. The copyright on this publication belongs to Peeters Publishers. As author you are licensed to make printed copies of the pdf or to send the unaltered pdf file to up to 50 relations. You may not publish this pdf on the World Wide Web – including websites such as academia.edu and open-access repositories – until three years after publication. Please ensure that anyone receiving an offprint from you observes these rules as well. If you wish to publish your article immediately on open- access sites, please contact the publisher with regard to the payment of the article processing fee. For queries about offprints, copyright and republication of your article, please contact the publisher via [email protected] AEGAEUM 39 Annales liégeoises et PASPiennes d’archéologie égéenne METAPHYSIS RITUAL, MYTH AND SYMBOLISM IN THE AEGEAN BRONZE AGE Proceedings of the 15th International Aegean Conference, Vienna, Institute for Oriental and European Archaeology, Aegean and Anatolia Department, Austrian Academy of Sciences and Institute of Classical Archaeology, University of Vienna, 22-25 April 2014 Edited by Eva ALRAM-STERN, Fritz BLAKOLMER, Sigrid DEGER-JALKOTZY, Robert LAFFINEUR and Jörg WEILHARTNER PEETERS LEUVEN - LIEGE 2016 98738_Aegaeum 39 vwk.indd 1 25/03/16 08:06 CONTENTS Obituaries ix Preface xiii Abbreviations xv KEYNOTE LECTURE Nanno MARINATOS Myth, Ritual, Symbolism and the Solar Goddess in Thera 3 A. -

Data Structure

Data structure – Water The aim of this document is to provide a short and clear description of parameters (data items) that are to be reported in the data collection forms of the Global Monitoring Plan (GMP) data collection campaigns 2013–2014. The data itself should be reported by means of MS Excel sheets as suggested in the document UNEP/POPS/COP.6/INF/31, chapter 2.3, p. 22. Aggregated data can also be reported via on-line forms available in the GMP data warehouse (GMP DWH). Structure of the database and associated code lists are based on following documents, recommendations and expert opinions as adopted by the Stockholm Convention COP6 in 2013: · Guidance on the Global Monitoring Plan for Persistent Organic Pollutants UNEP/POPS/COP.6/INF/31 (version January 2013) · Conclusions of the Meeting of the Global Coordination Group and Regional Organization Groups for the Global Monitoring Plan for POPs, held in Geneva, 10–12 October 2012 · Conclusions of the Meeting of the expert group on data handling under the global monitoring plan for persistent organic pollutants, held in Brno, Czech Republic, 13-15 June 2012 The individual reported data component is inserted as: · free text or number (e.g. Site name, Monitoring programme, Value) · a defined item selected from a particular code list (e.g., Country, Chemical – group, Sampling). All code lists (i.e., allowed values for individual parameters) are enclosed in this document, either in a particular section (e.g., Region, Method) or listed separately in the annexes below (Country, Chemical – group, Parameter) for your reference. -

From Prehistoric Villages to Cities Settlement Aggregation and Community Transformation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository From Prehistoric Villages to Cities Settlement Aggregation and Community Transformation Edited by Jennifer Birch 66244-093-0FM.indd244-093-0FM.indd iiiiii 118-02-20138-02-2013 111:09:271:09:27 AAMM First published 2013 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2013 Taylor & Francis The right of the editors to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data [CIP data] ISBN: 978-0-415-83661-6 (hbk) ISBN: 978-0-203-45826-6 (ebk) Typeset in Sabon by Apex CoVantage, LLC 66244-093-0FM.indd244-093-0FM.indd iivv 118-02-20138-02-2013 111:09:271:09:27 AAMM Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables xi Preface xiii 1 Between Villages and Cities: Settlement Aggregation in Cross-Cultural Perspective 1 JENNIFER BIRCH 2 The Anatomy of a Prehistoric Community: Reconsidering Çatalhöyük 23 BLEDA S. -

Readingsample

The TRANSMED Atlas. The Mediterranean Region from Crust to Mantle Geological and Geophysical Framework of the Mediterranean and the Surrounding Areas Bearbeitet von William Cavazza, François M. Roure, Wim Spakman, Gerard M. Stampfli, Peter A. Ziegler 1. Auflage 2004. Buch. xxiii, 141 S. ISBN 978 3 540 22181 4 Format (B x L): 19,3 x 27 cm Gewicht: 660 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Physik, Astronomie > Angewandte Physik > Geophysik Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Chapter 1 The Mediterranean Area and the Surrounding Regions: Active Processes, Remnants of Former Tethyan Oceans and Related Thrust Belts William Cavazza · François Roure · Peter A. Ziegler Abstract 1.1 Introduction The Mediterranean domain provides a present-day geo- From the pioneering studies of Marsili – who singlehand- dynamic analog for the final stages of a continent-conti- edly founded the field of oceanography with the publi- nent collisional orogeny. Over this area, oceanic lithos- cation in 1725 of the Histoire physique de la mer, a scien- pheric domains originally present between the Eurasian tific best-seller of the time (Sartori 2003) – to the tech- and African-Arabian plates have been subducted and par- nologically most advanced cruises of the R/V JOIDES tially obducted, except for the Ionian basin and the south- Resolution, the Mediterranean Sea has represented a cru- eastern Mediterranean. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

The Efforts Towards and Challenges of Greece's Post-Lignite Era: the Case of Megalopolis

sustainability Article The Efforts towards and Challenges of Greece’s Post-Lignite Era: The Case of Megalopolis Vangelis Marinakis 1,* , Alexandros Flamos 2 , Giorgos Stamtsis 1, Ioannis Georgizas 3, Yannis Maniatis 4 and Haris Doukas 1 1 School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, 15773 Athens, Greece; [email protected] (G.S.); [email protected] (H.D.) 2 Technoeconomics of Energy Systems Laboratory (TEESlab), Department of Industrial Management and Technology, University of Piraeus, 18534 Piraeus, Greece; afl[email protected] 3 Cities Network “Sustainable City”, 16562 Athens, Greece; [email protected] 4 Department of Digital Systems, University of Piraeus, 18534 Piraeus, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 8 November 2020; Accepted: 15 December 2020; Published: 17 December 2020 Abstract: Greece has historically been one of the most lignite-dependent countries in Europe, due to the abundant coal resources in the region of Western Macedonia and the municipality of Megalopolis, Arcadia (region of Peloponnese). However, a key part of the National Energy and Climate Plan is to gradually phase out the use of lignite, which includes the decommissioning of all existing lignite units by 2023, except the Ptolemaida V unit, which will be closed by 2028. This plan makes Greece a frontrunner among countries who intensively use lignite in energy production. In this context, this paper investigates the environmental, economic, and social state of Megalopolis and the related perspectives with regard to the energy transition, through the elaboration of a SWOT analysis, highlighting the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the municipality of Megalopolis and the regional unit of Arcadia.