AEGEAN FEASTI NG Pages 247-279 a MINOAN PERSPECTIVE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

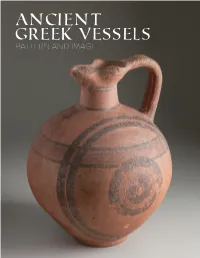

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

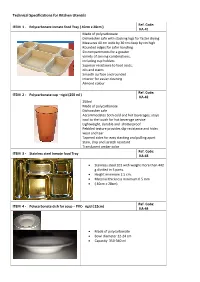

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils Ref. Code: ITEM 1 - Polycarbonate inmate food Tray ( 40cm x 28cm ) KA-41 Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe with stacking lugs for faster drying Measures 40 cm wide by 30 cm deep by cm high Rounded edges for safer handling Six compartments for a greater variety of serving combinations, including cup holders Superior resistance to food acids, oils and stains Smooth surface and rounded interior for easier cleaning Almond colour Ref. Code: ITEM 2 - Polycarbonate cup –rigid (250 ml ) KA-42 250ml Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe Accommodates both cold and hot beverages; stays cool to the touch for hot beverage service Lightweight, durable and shatterproof Pebbled texture provides slip-resistance and hides wear and tear Tapered sides for easy stacking and pulling apart Stain, chip and scratch resistant Translucent amber color Ref. Code: ITEM 3 - Stainless steel Inmate food Tray KA-43 • Stainless steel 201 with weight more than 442 g divided in 5 parts. • Height minimum 2.5 cm. • Material thickness minimum 0.5 mm • ( 40cm x 28cm) Ref. Code: ITEM 4 - Polycarbonate dish for soup – PVC- rigid ( 22cm) KA-44 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 350-360 ml Ref. Code: ITEM 5 - Plastic dish for salad – PVC- rigid KA-45 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 225-250 ml ITEM 6- Heavy Duty Frying-pan from ( 2 set of 6 pcs from the biggest until Ref. Code: the smallest size) KA-46 Set of 6 Pcs from the biggest until the smallest size) Size fir the biggest one : 30-035 x 15-19.0-15 x 2.5 6.0 • Weight: 0.6-1.5 kg • Material: stainless steel Ref. -

A Computational Translation of the Phaistos Disk Peter Revesz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln CSE Conference and Workshop Papers Computer Science and Engineering, Department of 10-1-2015 A Computational Translation of the Phaistos Disk Peter Revesz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cseconfwork Part of the Comparative and Historical Linguistics Commons, Computational Linguistics Commons, Computer Engineering Commons, Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons, Language Interpretation and Translation Commons, and the Other Computer Sciences Commons Revesz, Peter, "A Computational Translation of the Phaistos Disk" (2015). CSE Conference and Workshop Papers. 312. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cseconfwork/312 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Computer Science and Engineering, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in CSE Conference and Workshop Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Mathematical Models and Computational Methods A Computational Translation of the Phaistos Disk Peter Z. Revesz several problems. First, a symbol may be interpreted as Abstract— For over a century the text of the Phaistos Disk denoting many different objects. Second, the depicted object remained an enigma without a convincing translation. This paper could have many synonyms in the native language. Third, presents a novel semi-automatic translation method -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

Bonelli's Eagle and Bull Jumpers: Nature and Culture of Crete

Crete April 2016 Bonelli’s Eagle and Bull Jumpers: Nature and Culture of Crete April 9 - 19, 2016 With Elissa Landre Photo of Chukar by Elissa Landre With a temperate climate, Crete is more pristine than the mainland Greece and has a culture all its own. Crete was once the center of the Minoan civilization (c. 2700–1420 BC), regarded as the earliest recorded civilization in Europe. In addition to birding, we will explore several famous archeological sites, including Knossos and ancient Phaistos, the most important centers of Minoan times. Crete’s landscape is very special: defined by high mountain ranges, deep valleys, fertile plateaus, and caves (including the mythological birthplace of the ancient Greek god, Zeus) Rivers have cut deep, exceptionally beautiful gorges that create a rich presence of geological wealth and have been explored for their aromatic and medicinal plants since Minoan times. Populations of choughs, Griffon Vultures, Lammergeiers, and swifts nest on the steep cliffs. A fantastic variety of birds and plants are found on Crete: not only its resident bird species, which are numerous and include rare and endangered birds, but also the migrants who stop over on Crete during their journeys to and from Africa and Europe. The isolation of Crete from mainland Europe, Asia, and Africa is reflected in the diversity of habitats, flora, and avifauna. The richness of the surroundings results in an impressive bird species list and often unexpected surprises. For example, last year a Blue- cheeked Bee-eater, usually only seen in northern Africa and the Middle East, was spotted. Join us for this unusual and very special trip. -

Bowl Round 5 Bowl Round 5 First Quarter

NHBB B-Set Bowl 2017-2018 Bowl Round 5 Bowl Round 5 First Quarter (1) The remnants of this government established the Republic of Ezo after losing the Boshin War. Two and a half centuries earlier, this government was founded after its leader won the Battle of Sekigahara against the Toyotomi clan. This government's policy of sakoku came to an end when Matthew Perry's Black Ships forced the opening of Japan through the 1854 Convention of Kanagawa. For ten points, name this last Japanese shogunate. ANSWER: Tokugawa Shogunate (or Tokugawa Bakufu) (2) Xenophon's Anabasis describes ten thousand Greek soldiers of this type who fought Artaxerxes II of Persia. A war named for these people was won by Hamilcar Barca and led to his conquest of Spain. Famed soldiers of this type include slingers from Rhodes and archers from Crete. Greeks who fought for Persia were, for ten points, what type of soldier that fought not for national pride, but for money? ANSWER: mercenary (prompt on descriptive answers) (3) The most prominent of the Townshend Acts not to be repealed in 1770 was a tax levied on this commodity. The Dartmouth, the Eleanor, and the Beaver carried this commodity from England to the American colonies. The Intolerable Acts were passed in response to the dumping of this commodity into a Massachusetts Harbor in 1773 by members of the Sons of Liberty. For ten points, identify this commodity destroyed in a namesake Boston party. ANSWER: tea (accept Tea Act; accept Boston Tea Party) (4) This location is the setting of a photo of a boy holding a toy hand grenade by Diane Arbus. -

Gareth Owens and His Decipherment of the Phaistos Disc I Have Taken A

Gareth Owens and His Decipherment of the Phaistos Disc I have taken a look at Owens’s website (http://www.teicrete.gr/daidalika), have read the various texts there that pertain to the Phaistos Disc, and have watched his TEDx-Talk twice. 1. First, some preliminary remarks. There are four scripts in prehistoric Crete that write at least two languages. The 4 scripts are those on the Phaistos Disc (PhD, hereafter) and on documents written in Cretan Pictographic/Hieroglyphic (CP herafter), Linear A, and Linear B (usually AB, hereafter). The languages are Greek in the Linear B documents and whatever language or languages that were written on the Disc and on the CP and Linear A documents. Linear B (ca. 1400-1200 BCE) was deciphered in 1952 (Ventris & Chadwick, Documents in Mycenaean Greek) and it records our earliest Greek texts. The script is a syllabary consisting of some 90+ signs. It is obvious that these signs were adapted from the signs in the earlier script Linear A (Godart & Olivier, Recueil des inscriptions en Linéaire A), which was in use in Crete from about 1900 to 1500 BCE. These two scripts use abstract signs, most of which do not resemble any object. Many of the Linear A signs developed from the slightly earlier CP script (ca. 1950 to 1700 BCE; Godart & Olivier, Corpus inscriptionum hieroglyphicarum Cretae), and most of these Pictographic signs are obviously schematic drawings of real objects (persons, animals like a dog head or a fly, man-made objects like an ax, and plants like a tree or branch). -

Greek Pottery Gallery Activity

SMART KIDS Greek Pottery The ancient Greeks were Greek pottery comes in many excellent pot-makers. Clay different shapes and sizes. was easy to find, and when This is because the vessels it was fired in a kiln, or hot were used for different oven, it became very strong. purposes; some were used for They decorated pottery with transportation and storage, scenes from stories as well some were for mixing, eating, as everyday life. Historians or drinking. Below are some have been able to learn a of the most common shapes. great deal about what life See if you can find examples was like in ancient Greece by of each of them in the gallery. studying the scenes painted on these vessels. Greek, Attic, in the manner of the Berlin Painter. Panathenaic amphora, ca. 500–490 B.C. Ceramic. Bequest of Mrs. Allan Marquand (y1950-10). Photo: Bruce M. White Amphora Hydria The name of this three-handled The amphora was a large, two- vase comes from the Greek word handled, oval-shaped vase with for water. Hydriai were used for a narrow neck. It was used for drawing water and also as urns storage and transport. to hold the ashes of the dead. Krater Oinochoe The word krater means “mixing The Oinochoe was a small pitcher bowl.” This large, two-handled used for pouring wine from a krater vase with a broad body and wide into a drinking cup. The word mouth was used for mixing wine oinochoe means “wine-pourer.” with water. Kylix Lekythos This narrow-necked vase with The kylix was a drinking cup with one handle usually held olive a broad, relatively shallow body. -

A Standard for Pottery Analysis in Archaeology

A Standard for Pottery Analysis in Archaeology Medieval Pottery Research Group Prehistoric Ceramics Research Group Study Group for Roman Pottery Draft 4 October 2015 CONTENTS Section 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Aims 1 1.2 Scope 1 1.3 Structure 2 1.4 Project Tasks 2 1.5 Using the Standard 5 Section 2 The Standard 6 2.1 Project Planning 6 2.2 Collection and Processing 8 2.3 Assessment 11 2.4 Analysis 13 2.5 Reporting 17 2.6 Archive Creation, Compilation and Transfer 20 Section 3 Glossary of Terms 23 Section 4 References 25 Section 5 Acknowledgements 27 Appendix 1 Scientific Analytical Techniques 28 Appendix 2 Approaches to Assessment 29 Appendix 3 Approaches to Analysis 33 Appendix 4 Approaches to Reporting 39 1. INTRODUCTION Pottery has two attributes that lend it great potential to inform the study of human activity in the past. The material a pot is made from, known to specialists as the fabric, consists of clay and inclusions that can be identified to locate the site at which a pot was made, as well as indicate methods of manufacture and date. The overall shape of a pot, together with the character of component parts such as rims and handles, and also the technique and style of decoration, can all be studied as the form. This can indicate when and how a pot was made and used, as well as serving to define cultural affinities. The interpretation of pottery is based on a detailed characterisation of the types present in any group, supported by sound quantification and consistent approaches to analysis that facilitate comparison between assemblages. -

Table of Contents 1

Maria Hnaraki, 1 Ph.D. Mentor & Cultural Advisor Drexel University (Philadelphia-U.S.A.) Associate Teaching Professor Official Representative of the World Council of Cretans Kids Love Greece Scientific & Educational Consultant Tel: (+) 30-6932-050-446 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Table of Contents 1. FORMAL EDUCATION ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. ADDITIONAL EDUCATION .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 3. EMPLOYMENT RECORD ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 3.1. Current Status (2015-…) ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 3.2. Employment History ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 3.2.1. Teaching Experience ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 3.2.2. Research Projects .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Although Crete Seems to Have Been First Inhabited in the Palaeolithic (Strasser Et Al

Although Crete seems to have been first inhabited in the Palaeolithic (Strasser et al. 2010), another colonization of the island occurred at the end of the Neolithic (Broodbank and Strasser 1991). From then, the internal chronology of Crete follows two systems, a ceramic development (Early, Middle, and Late Minoan with internal subdivisions) and a system based on architectural phases: Prepalatial (EM–MM IA, c.3000–1900 ), Protopalatial (MM IB–II, 1900–1750), Neopalatial (MM III–LM IB, 1750–1490), Final Palatial (LM II–IIIA:2/B1, 1490–1300), and Post Palatial (LM IIIB–C, 1300–1100). The last two periods comprise Mycenaean Crete. The Cretan “Hieroglyphic” and Linear A scripts were developed in the Protopalatial period (Godart and Olivier 1996; Younger 2005); Linear A survives into the Neopalatial period (Godart and Olivier 1976–1985; Younger 2000); and Linear B writes Greek in the Final Palatial period (Killen and Olivier 1989). There are three main ways of identifying females in Aegean art: costume, hairstyle (following age grades), and skin color in fresco. Females are always clothed (males may be nude) and women are often depicted in elaborate “court” dress (see below), textiles made of wool that were also exported to Egypt and the Near East. The fairly consistent Egyptian color conven- Blakolmer 2004, 2012) was also followed in Minoan fresco (Hood 1985). people before the Malia Workshop (MM II). There are few representations of women on pot- tery but females are prominent in the frescoes. Texts give us limited information. In Linear B women were denoted by the logogram *102 MUL . -

Print This Article

Byzantina Symmeikta Vol. 29, 2019 Byzantine families in Venetian context: The Gavalas and Ialinas family in Venetian Crete (XIIIth- XIVth centuries) ΓΑΣΠΑΡΗΣ Χαράλαμπος Institute of Historical Research, Athens https://doi.org/10.12681/byzsym.16249 Copyright © 2019 Χαράλαμπος Γάσπαρης To cite this article: ΓΑΣΠΑΡΗΣ, (2019). Byzantine families in Venetian context: The Gavalas and Ialinas family in Venetian Crete (XIIIth- XIVth centuries). Byzantina Symmeikta, 29, 1-132. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/byzsym.16249 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 30/09/2021 15:19:54 | INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH ΙΝΣΤΙΤΟΥΤΟ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΚΩΝ ΕΡΕΥΝΩΝ SECTION OF BYZANTINE RESEARCH ΤΟΜΕΑΣ ΒΥΖΑΝΤΙΝΩΝ ΕΡΕΥΝΩΝ NATIONAL HELLENIC RESEARCH FOUNDATION ΕΘΝΙΚΟ IΔΡΥΜΑ ΕΡΕΥΝΩΝ CHARALAMBOS GASPARIS EFI RAGIA Byzantine Families in Venetian Context: THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE PROVINCIAL ADMINISTRATION OF THE TheBYZAN GavalasTINE E andMPI REIalinas (CA 600-1200):Families I.1.in T HVenetianE APOTHE CreteKAI OF (XIIIth–XIVthASIA MINOR (7T HCenturies)-8TH C.) ΤΟΜΟΣ 29 VOLUME ΠΑΡΑΡΤΗΜΑ / APPENDIX ΑΘΗΝΑ • 20092019 • ATHENS http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 30/09/2021 15:19:54 | http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 30/09/2021 15:19:54 | http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 30/09/2021 15:19:54 | ΒΥΖΑΝΤΙΝΑ ΣΥΜΜΕΙΚΤΑ 29 ΠΑΡΑΡΤΗΜΑ ΒΥΖΑΝΤΙΝΑ SYMMEIKTA 29 APPENDIX http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 30/09/2021 15:19:54 | NATIONAL HELLENIC RESEARCH FOUNDATION INSTITUTE OF