Solo Singing for Choir Boys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1994 June.Pdf

HELLY HANSEN LIFA Hurry while stocks last Long Sleeve, Round Neck, Colour: Red, Small, Med, Large, X Large. Also short sleeve, Navy, X Small, Med only. □ Major stockists of Walsh shoes. All your needs for fellrunning. □ Not just a shop, a centre for advice and information. □ Write or ring for price list and colour brochure. □ Switch, Visa, Access telephone orders taken 34A Kirkland, Kendal, CUMBRIA LA9 5AD Tel/Fax 0539 731012 Bit at the Front Neil Denby Once again we find ourselves tinged British title with a 1st and a 2nd, with sadness in our sport. An ex giving him a total of 41 points. perienced competitor, well aware of Nearest rival is J Parker with two The Association has bought some the hazardous nature of the sport, 3rds and thus 36 points and Ian right expensive computer well equipped and with mountain Holmes close on his heels with 35. equipment to try to drag us into the and navigational skills, tragically The competition may get even hotter 20th century. If you can provide died at the Kentmere race. The now that the news is out that the articles etc. on 3+" discs of DOS or DFS format (not Unix); preferably initial verdict was hypothermia, but William Hill sponsorship deal has in ASCII; then we can handle them the inquest is yet to report. Judith been accepted by the FRA, details in easily - the amount of stuff that Taylor will be sadly missed by the this issue. For the ladies, Andrea comes that is obviously a computer sport and we join in sending our Priestley is ahead with maximum print out is growing but still needs condolences to her family. -

The Warburtons of Edenfield

The Warburtons of Edenfield Last Updated 4th August 2021 ©2018 to 2021 Ray Warburton PREFACE The Warburtons of Edenfield first appear in the Halmote Records of Tottington Manor in the early 16th century although there is an earlier mention of a probable ancestor on a rental from 1442. A paper called Warburton References in the Halmote Records of Tottington Manor can be found on the Pages page of the website. The tree is based on an original tree provided by Anthony Carter, with additional input from Nicolas Blackhurst, and David Hardman. It has been considerably extended by my own research and information on additional lines from Robert Warburton, Colin Warburton, and Sharron Newhouse. A paper called Edenfield Clan and Related Peters can be found on the Papers page of the website. There are two matching DNA Profiles from the clan, including a BigY result. There are several other matches from clans with origins in the area which together form The Lancashire Group. It is likely these other clans are branches of the Edenfield clan though the exact links have yet to be found. Table of Contents Preface -- Edenfield Clan i Surnames 1 Descendants of Thomas Warburton & Unknown First Generation 2 Second Generation 4 Third Generation 5 Fourth Generation 6 Fifth Generation 7 Sixth Generation 9 Seventh Generation 10 Eighth Generation 11 Ninth Generation 13 Tenth Generation 15 Eleventh Generation 20 Twelfth Generation 33 Thirteenth Generation 52 14th Generation 64 15th Generation 75 Place Index 81 Person Index 92 ii Surnames A Ashworth, Aynge B Barnes, -

Ramblers Gems a Spring Vale Rambling Class Publication

Ramblers Gems A Spring Vale Rambling Class Publication Volume 1, Issue 10 10th July 2020 For further information or to submit a contribution email: [email protected] I N S I D E T H I S I SSUE Monster Alert 1 Thought of the Week / Monster Alert 2 A Darwen to Mellor Walk 3 Haslingden Grane A Story built in Stone 4 Walking the Tolkien Trail 5/ A Bit more than a Day Trip 6 Royal Hunting Grounds 7 Thought of the week Giant Hogweed has been listed as the most dangerous plant in Britain. This deadly plant is in the news again this year for its severe dermal reactions in both humans and animals after only a brief contact. The plant is now rapidly spreading throughout the UK and is usually found around watersides as well as in grassy areas and open woods. Exposure to hogweed sap can occur simply by Watch the sunrise at least once a year. brushing against it with bare skin and this causes skin Put a lot of marshmallows in your hot chocolate. ulcerations, fluid-filled blisters and vomiting. Signs can Lie on your back and look at the stars. develop rapidly within a few hours and open skin Never buy a coffee table you can’t put your feet on. Never pass up a chance to jump on a trampoline. lesions pose the risk of secondary infections. The Don’t overlook life’s small joys while searching for the symptoms are further aggravated by sunlight. big ones. Please take care, especially with children and dogs H. -

2020 Organised by Wern

2020 Association of Northern Car Clubs Wern Ddu Organised by Practical Safety Weekend 15 / 16th February Volume 11 : Issue 3: March 2020 : Maurice Ellison Pg. 44 Radio Mutterings - Cambrian Pg. 45 Gemini Motorsport Team Contents Pg. 46 Grumpy Old Git Pg. 47 Inside the Industry Front Cover :- Pg. 48 Inside the Industry Pg. 49 Inside the Industry Safety Weekend Pg. 50 Inside the Industry Pg. 2 Contents Pg. 51 Northern Classic Trial Pg. 3 Chairmans Chat Pg. 52 Northern Classic Trial Pg. 4 SD34MSG Contacts Pg. 53 Ewan Tindall’s R2 Pg. 5 Member Club Contacts Pg. 54 NESCRO Challenge - 2020 Calendar Pg. 6 2020 SD34MSG Championships Positions Pg. 55 BRMC Pg. 7 2020 SD34MSG Championships Positions Pg. 56 ANWCC 2020 Calendar Pg. 8 Under 18 Championship Registration Pg. 57 ANWCC 2020 Calendar Pg. 9 2020 Championship Registration Pg. 58 ANWCC 2020 Calendar Pg. 10 2020 Championship Classes Pg. 59 ANWCC 2019 Championship Positions Pg. 11 2020 SD34MSG Calendar & Championships Pg. 60 ANWCC 2019 Championship Positions Pg. 12 2020 SD34MSG Calendar & Championships Pg. 61 ANWCC 2019 Championship Positions Pg. 13 2020 SD34MSG Calendar & Championships Pg. 62 ANWCC 2020 Championships Registration Pg. 14 Around the Clubs : Clitheroe & DMC Pg. 63 ANWCC 2020 Championships Registration Pg. 15 Around the Clubs : Clitheroe & DMC Pg. 64 Cars for Sale Pg. 16 Around the Clubs : Clitheroe & DMC Pg. 65 Odds, Sods & Bodkins & Events Pg. 17 Around the Clubs : Knutsford Pg. 66 Odds, Sods & Bodkins & Events Pg. 18 Around the Clubs : Blackpool South Shore Pg. 67 Odds, Sods & Bodkins & Events Pg. 19 Around the Clubs : Liverpool & More Pg. -

West Pennine Moors Moorland Fringe

A vegetation survey of the West Pennine Moors moorland fringe a report for Natural England by Graeme Skelcher Ecological Consultant 8 Coach Road Warton, Carnforth Lancashire LA5 9PP 01524 720243 [email protected] http://graemeskelcher.sharepoint.com December 2013 A vegetation survey of the West Pennine Moors moorland fringe, 2013 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHODS 3 Key to Maps 1 - 4 4 Map 1: West Pennines moorland fringe NVC communities - Haslingden zone NW 5 Map 2: West Pennines moorland fringe NVC communities - Haslingden zone SE 6 Map 3: West Pennines moorland fringe NVC communities - Anglezarke zone NW 7 Map 4: West Pennines moorland fringe NVC communities - Anglezarke zone SE 8 Map 5: West Pennines moorland fringe Phase 1 habitats - Anglezarke zone NW 9 Map 6: West Pennines moorland fringe Phase 1 habitats - Anglezarke zone SE 10 Map 7: West Pennines moorland fringe BAP habitats - Haslingden zone NW 11 Map 8: West Pennines moorland fringe BAP habitats - Haslingden zone SE 12 Map 9: West Pennines moorland fringe BAP habitats - Anglezarke zone NW 13 Map 10: West Pennines moorland fringe BAP habitats - Anglezarke zone SE 14 2 SUMMARY DESCRIPTION 15 Table 1: Extent of NVC communities within the surveyed WPM moorland fringe 17 Table 2: Extent of Biodiversity habitats within the surveyed WPM moorland fringe 18 Table 3: Peat-depth measurements recorded within the WPM moorland fringe 19 3 NVC COMMUNITY DESCRIPTIONS 20 3.1 Bog, flush and fen communities 20 3.2 Heath and acid grassland communities 24 3.2 Unimproved and semi-improved -

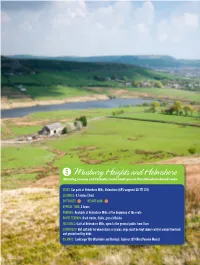

Musbury Heights and Helmshore Stunning Scenery and Fantastic Views Await You on This Helmshore-Based Route

5 Musbury Heights and Helmshore Stunning scenery and fantastic views await you on this Helmshore-based route. START: Car park at Helmshore Mills, Helmshore (GPS waypoint SD 777 214) DISTANCE: 4.5 miles (7km) DIFFICULTY: HEIGHT GAIN: APPROX. TIME: 2 hours PARKING: Available at Helmshore Mills at the beginning of the route ROUTE TERRAIN: Hard tracks, fields, grass hillsides FACILITIES: Café at Helmshore Mills, open to the general public from 11am SUITABILITY: Not suitable for wheelchairs or prams, dogs must be kept under control around livestock and ground nesting birds OS MAPS: Landranger 103 (Blackburn and Burnley), Explorer 287 (West Pennine Moors) David Turner LANCASHIRE WALKS MUSBURY HEIGHTS AND HELMSHORE A four and a half mile route, which starts from the Helmshore is a village in the first dedicated cotton mill and reservoirs were built in the 19th Blackburn bus station and quiet village of Helmshore and takes the walker over Rossendale Valley, south of was located immediately below century, Haslingden Grane had a nearby Rawtenstall bus station, moorland, through valleys and over hilltops, before Haslingden. The village sits where Alden Farm stands today. population of around 1,300 and which is on Bacup Road. The The walker’s view skirting nearby Holden Wood Reservoir. beside and includes the old the remains of some buildings East Lancashire Railway also township of Musbury, part Industry expanded as time went can still be seen. runs between Rawtenstall, Bury David Turner discovers Helmshore Due to the terrain and number of hills and stiles of Haslingden and part of on and larger mills were built in and Heywood, but this service with this route encountered, we can’t class this as an accessible walk. -

Haslingden Clan Part 1 Descendants of Thomas

Robert Warburton b. abt 1697, Hutch Bank, Haslingden, Lancashire Thomas Warburton d. 12 May 1698, Haslingden, Lancashire b. 1737, Todhall, Haslingden, Lancashire Henry Warburton Anne Warburton ch. 31 Jan 1697, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire d. 1738, Haslingden, Lancashire b. 1793, Haslingden, Lancashire b. 1820, Haslingden, Lancashire ch. 5 Dec 1737, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire d. 1793, Haslingden, Lancashire ch. 30 Apr 1820, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire bur. 1 Dec 1793, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire & John Trickett Mary Warburton b. abt 1815 b. 1698, Haslingden, Lancashire Mary Warburton d. 1849, Ewood Bridge, Lancashire d. 1701, Haslingden, Lancashire b. 1739, Hutch Bank, Haslingden, Lancashire bur. 1 Apr 1849, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire bur. 14 May 1701, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire d. 1758, Haslingden, Lancashire m. 1841, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire Haslingden Clan ch. 10 Apr 1698, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire ch. 8 Dec 1739, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire Anne Warburton Robert Warburton James Warburton b. 1820, Haslingden, Lancashire b. 1699, Haslingden, Lancashire b. 1742, Haslingden Grane, Lancashire ch. 30 Apr 1820, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire ch. 19 Nov 1699, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire d. 1755, Priest’s Intake, Haslingden, Lancashire & Thomas Lord Part 1 bur. 3 Jul 1755, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire b. 1817, Edenfield, Lancashire ch. 29 Aug 1742, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire m. 10 Nov 1850, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire Mary Warburton b. abt 1702, Haslingden, Lancashire ch. 25 Jan 1703, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire Elizabeth Warburton John Warburton b. abt 1745, Haslingden Grane, Lancashire b. 1821, Haslingden, Lancashire ch. 12 Jan 1745, Haslingden, St James, Lancashire d. 1822, Haslingden, Lancashire Descendants of Thomas bur. -

Nov 2019 News Letter

www.nmrs.org.uk November 2019. www.nmrs.org.uk Editor. Graham Topping News from our Society riting this before our Autumn meeting news of that event will be in the February Chapel Lodge.Chapel Lane. Newsletter. However Reports should be going on our website sometime this month West Bradford. Clitheroe. Wso please look out for them. If anyone wants a physical copy please let me know Lancs. BB74SN. Tel:- which you are interested in either by email (at the end) or via our Secretary (address further on). 07973905883. Email:- There are also interesting presentations planned. Thank you so much to all who attend our [email protected] meetings. We do realise many of you live too far away to come but we do appreciate your support. In this Issue. Well this year has flown by and 2020 will soon be upon us. Enclosed with this mailing is the membership renewal form for 2020. Once again we have been able to hold our membership Page. prices at the same level as this year. Please complete your form as soon as possible in order to 1. News from our Society. help our Membership Secretary, Gary Topping. Thank you to all who gift aid their membership 2. Website News. but please remember to inform us if your circumstances change and we are no longer able to 3. Company of Mines Royal. claim it. May I also remind you our privacy policy document is on our website. 4. Suggested Future Articles. It is also the time to consider Committee nominations. If you are interested in any of the 5. -

Magister Journal of the Old Blackburnians’ Association

MAGISTER JOURNAL OF THE OLD BLACKBURNIANS’ ASSOCIATION BiSce JOrobti* No 1 AUGUST 1963 SCOTTISH BRANCH Top Post for Mr Taylor Mr Milton Whalley MAY BE FORMED T a y lo r , who was a pupil at QEGS from 1919 to 1929, ^ NEW BRANCH o f the Old Blackburnians5 Association may shortly be formed has been appointed deputy in Scotland. regional director of the East ern Region of the National Association records show that at least 20 old boys are now living in Scotland, and Agricultural Advisory Ser the idea for, initially, an occasional get-together comes from Mr Paul N. Price, who vice. was at the school from 1948 to 1954. Mr Taylor took his BA degree in agriculture at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, in 1932, Mr Price, who lives at 18, and was a poultry farmer at Faskally Avenue, Bishopbriggs, Wilpshire, Blackburn, until 1940. TO BE VICAR Glasgow (tel. Bishopbriggs 3936) NEW HEADSHIP He received his M A degree in asks : “ What is the best way to 1936. AT BLACKBURN try to organise an occasional FOR MR BENSON From 1934 to 1946 he was The Rev William David lunch or some function, then we M r N. S. T. B e n s o n , head technical advisor and director of R o b in s o n (32), senior curate of can have a Glasgow branch of master of Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School from 1948 to the experimental research farm Lancaster Priorv, is to be the the OBs ? ” 1956, has been appointed head for the Poultry Association of new vicar of St. -

Where Did the Stone Slate Roofs of Rossendale Come From.Pdf

WHERE DID THE STONE SLATE ROOFS OF ROSSENDALE COME FROM? ARTHUR BALDWIN: GROUNDWORK ROSSENDALE Some notes on older quarries supplying this distinctive product before the era of Welsh slate. 1 INTRODUCTION Stone slate roofs are a rich and characterful feature of early stone buildings and an important aspect of the English landscape. In regional terms, Pennine sandstone roofs are quite hefty and laid at a very low pitch. They may not be so charming as the roofs of the limestone regions of the Midlands and the South, but they have a visual unity and harmony with the landscape and style of local architecture. With great skill and adaptation our ancestors used local materials from their immediate surroundings to create farmhouses and cottages which almost seem naturally rooted in the in the Pennine valleys and hillsides. 2 DEFINITION The term stone slate includes many varieties of essentially sedimentary rock, especially limestones and sandstones. All must be naturally fissile ie capable of being split into comparatively thin pieces. Unlike true slate, an altered metamorphic rock which splits along lines of cleavage, stone slates always split along lines of lamination parallel to the bedding planes, often facilitated by the presence of mica flakes. Several geological horizons in the local Millstone Grit and Coal Measures display these characteristics and have been used locally, but often only in small or moderate amounts. 3 LOCAL SUPPLIES A short newspaper report in the Bacup Times, August 1 1891 describes a ramble to Green's Clough near Deerplay alluding to Heald Flag Rock; mention being made that almost all the old houses in Rossendale were roofed with tiles from these quarries. -

Guided Walks Programme 2011 FREE Easy to Hard

ALL WALKS Each walk is circular, led by a Guide and is free. ROSSENDALE ARE They are of different types and standards from Guided Walks Programme 2011 FREE easy to hard. The fi rst two Sundays of the month are heritage walks with talks at specifi c points; the Incorporating Valley of Stone third Sunday walks are longer with less talking. Most of the walks start where car parking is available nearby and at What if I have further questions? a place accessible by public transport. Please contact Arthur Baldwin on 01254 669060 Rossendale or email Do I have to bring anything? [email protected] Guided Walks These are walks in open countryside, sometimes in for more information about quarries, so you will be more comfortable if you wear Groundwork Pennine Lancashire visit www.gwpl.co.uk Programme 2011 strong shoes or walking boots for the rougher ground. The weather can change, so bring a waterproof, and Supported by Rossendale Borough Council, don’t forget that Rossendale is hilly, and it can be cooler Lancashire County Council and on the tops, so wear warm clothing. On third Sunday Pennine Prospects Watershed Landscape walks you will need to bring a packed lunch and drink. What about bad weather? The Guide will be at the start to meet you whatever the weather. Adverse weather doesn’t normally stop a walk, but the Guide may change a route to suit prevailing conditions. All our walks bring you back to the start point. What about my dog? We regret that dogs are not permitted on any of the walks, with the exception of guide and hearing dogs. -

Rapid Growth and a New Era of Quarrying

Rapid growth and a new era of quarrying Quick Facts In the 1780s the development of steam engines and new railways meant that towns and industries, all needing stone, could grow quickly. Steam engines were a very important part of the Industrial Revolution, and were used in a variety of industries from mills to mining, improving productivity and technology, and crucially allowing transport of goods by rail. In the Rossendale valley, the first railway was built in 1846, 16 years after the Liverpool-Manchester railway. As well as goods and materials for industry, rocks and stone for building could now be moved around more easily, both locally, to other parts of the country, and abroad. This meant there was a rapid expansion in hillside quarrying, with the stone being transported to build towns and cities all over Britain. At its peak from 1870—1890, stone quarrying was the third largest workforce in Rossendale, with over 3000 men employed. Somebody’s been along and rubbed out some of the words on our information sheets — can you fill in the gaps? In order to transport stone from the quarries high on the hillsides to the railways below, many miles of ……………. were constructed down steep inclines. These tramways were not steam powered, but used long ………………... attached to circular drums at the top, and the weight of ……………...to lower the stone down. Stone was now needed on a much larger scale for: (name 3 uses) Changes in stone working Early stone Random Rubble. This method of building used stone that was put together without trying to create regular shape blocks or courses and used whatever stone was available.