Devolution of Les Bleus As a Symbol of a Multicultural French Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Bilan De La Saison De L'asse 2018-2019

ÉDITION NUMÉRIQUE Mardi 11 juin 2019 - Supplément - Loire LE BILAN DE LA SAISON DE L’ASSE 2018-2019 Saint-Etienne coupe d’europe ! William Saliba au micro fête avec les joueurs et le public la qualification des Verts en Ligue europa, concrétisation d’une saison réussie. Photo Yves SALVAT 154259800 W4202 - V0 Mardi 11 juin 2019 SUPPLÉMENT 3 FOOTBALL Ligue 1 La régularité et le printemps fleuri de victoires ont payé En plus d’avoir fini fort, l’AS- SE a fait preuve d’une belle régularité, terminant, au terme d’un sprint final haletant, à la 4e place la seule saison où ce strapon- tin est seul qualificatif pour la Ligue Europa. Chapeau. près un début de saison A poussif, une victoire, trois nuls et une défaite pour débuter. Les Verts étaient 14e après le revers à Paris avant d’enchaîner trois victoires de rang pour grim- per à la 4e place fin septembre. L’AS Saint-Étienne a occupé ce rang dix-sept fois en trente-huit journées, preuve d’une régulari- té exemplaire durant la saison, qualité essentielle pour bien fi- gurer en Ligue 1. Lors de chaque phase, l’équipe a pris trente-trois points. « L’important c’est la ré- gularité », disait Jean-Louis Gas- set en janvier. Les Verts ont validé leur billet pour l’Europe en l’emportant devant Nice (3-0, 37e journée). Photo Progrès/Yves SALVAT À Caen, le déclic les points perdus. Une date mar- c’est là qu’on a sorti l’idée de mal de pépins », expliquait Jean- de lancer dans le grand bain des Portés par leur maître à jouer quera la saison des Verts au fer dire : “Et si on était invaincus Louis Gasset après le dernier joueurs issus du centre de forma- Wahbi Khazri, en feu durant la rouge, le 16 mars : six jours plus jusqu’à la fin ? Car maintenant, match à Angers, englobant, les tion, dont deux en particulier et première moitié de la saison, ils tôt, ils s’inclinent 1-0 face à Lille les équipes sont jouables”. -

Sir Alex Ferguson

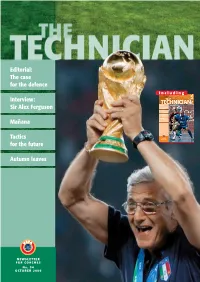

Editorial: The case for the defence Including Interview: Sir Alex Ferguson Mañana Tactics for the future Autumn leaves NEWSLETTER FOR COACHES N O .34 OCTOBER 2006 IMPRESSUM EDITORIAL GROUP Andy Roxburgh Graham Turner Frits Ahlstrøm PRODUCTION André Vieli Dominique Maurer Atema Communication SA Printed by Cavin SA COVER Having already won the UEFA Champions League with Juventus, Marcello Lippi pulled off a unique double in winning the World Cup with Italy this summer. (PHOTO: ANDERSEN/AFP/GETTY IMAGES) FABIO CANNAVARO UP AGAINST THIERRY HENRY IN THE WORLD CUP FINAL. THE ITALIAN DEFENDER WAS ONE OF THE BEST PLAYERS IN THE COMPETITION. BARON/BONGARTS/GETTY IMAGES BARON/BONGARTS/GETTY 2 THE CASE FOR THE DEFENCE EDITORIAL the French and, in the latter stages, FC Barcelona’s centre back Carles the Italians. On the other hand, the Puyol proved that star quality is not BY ANDY ROXBURGH, UEFA Champions League finalists the preserve of the glamour boys UEFA TECHNICAL DIRECTOR (plus seven other top teams) favoured who play up front. Top defenders and the deployment of one ‘vacuum their defensive team-mates proved cleaner’, as the late, great Rinus that good defensive play is a prerequi- Michels described the role. Interest- site to team success in top-level ingly, many of these deep-lying mid- competitions. Italy won the FIFA World Cup 2006 field players have become the initia- with a masterly display in the art of tors of the build-up play, such as The dynamics of football mean that defending. Two goals against, one Italy’s Andrea Pirlo. the game is always in flux. -

Footballeur Au Plus Tard – Allez Savoir – Le 9 Juillet Prochain, Jour De La Finale De La Coupe Du Monde À Berlin

Bleu Rouge 1 Noir Jaune LIGUE DES CHAMPIONS ARSENAL EN FINALE À PARIS Un penalty arrêté par Lehmann à la 88e minute a offert aux Gunners d’Arsène Wenger, Thierry Henry (notre photo) et Robert Pires, hier sur le terrain de Villarreal (0-0), une place en finale de la Ligue des champions, le 17 mai au Stade de France. Ils y défieront le vainqueur de l’autre demi-finale qui aura lieu ce soir, entre Barcelone et l’AC Milan (aller 1-0). (Pages 6 à 8) (Photo Pierre Lahalle) e o / *61 ANNÉE - N 18 929 0,80 France métropolitaine Mercredi 26 avril 2006 www.lequipe.fr T 00106 - 426 - F: 0,80 E 3:HIKKLA=[UU]U^:?a@e@c@q@k; LE QUOTIDIEN DU SPORT ET DE L’AUTOMOBILE « J’ARRIVAIS A LA FIN » Zinédine Zidane l’a officialisé hier : il se retirera au terme de la prochaine Coupe du monde, à trente-quatre ans. L’usure physique et les résultats décevants du Real Madrid, son club depuis 2001, ont poussé le capitaine des Bleus à clore une carrière extraordinaire. (Pages 2 à 5) LE FOL ESPOIR OILÀ, c’est dit. Pour de bon. Zinédine V Zidane ne sera plus footballeur au plus tard – allez savoir – le 9 juillet prochain, jour de la finale de la Coupe du monde à Berlin. C’est-à-dire demain. Nous avions beau nous en douter depuis quelques mois, depuis quelques semaines, tenter de nous habituer Noir Bleu à cette idée qu’à trente-quatre ans passés, au-delà de l’été qui s’annonce, Zinédine Noir Bleu Zidane n’aurait plus envie de nous enchanter balle au pied, nous sommes tous un peu Rouge Jaune tristes depuis hier. -

John Marks Public Discourse and Football in France After

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Nottingham John Marks Public Discourse and Football in France after 1998 Over the course of four World Cup campaigns (1998, 2002, 2006, 2010) and four European Championships (2000, 2004, 2008, 2012), the French national football team has undoubtedly experienced the most eventful and dramatic period in its history, surpassing the football champagne era of the 1980s in terms of both success and controversy. As far as playing performance is concerned, there have been notable successes in three tournaments (1998, 2000, 2006) and relatively ignominious exits in the group stages of others (2002, 2008, 2010), whilst in the 2012 European Championships the team lost tamely to Spain at the quarter final stage. However, the significance of the team’s exploits for the French nation has frequently gone far beyond straightforward joy or disappointment as a reaction to results on the pitch. In short, a turbulent, intense and complex relationship has developed between les Bleus and the French nation. France’s World Cup victory as host nation in 1998 gave football a new profile and significance in French public life. The extraordinary outpouring of popular feeling and attendant mediatisation of this “liesse populaire” following France’s World Cup victory in 1998 in retrospect constituted a major turning point with regard to France’s relationship with football. As well as gaining a new popularity with the French public in general, a number of French intellectuals – a group which had previously tended to be rather dismissive of football – found themselves converted by the wave of national celebration: “L’intelligentsia « anti- foot », encore prépondérante avant le mondial, se délite devant l’unanimisme national et l’admiration internationale” (Abdallah 2000: 6). -

MBAPPÉÉ À LA POURSUITE DE PAPIN ET GONDET P

RÉCIT KATOTO, L’ÉTOILE MYSTÉRIEUSE p. 32 décryptage MBAPPMBAPPÉÉ À LA POURSUITE DE PAPIN ET GONDET p. 24 analyse coulisses POURQUOI ILS LESVRAIS SONT FADASDE CHANTIERSDE Nikki & • BALBALOTOTELLIELLI FS 0 p. 18 COURBIS 5 COURBIS , Frankie 4 p. 28 CH • Photo | $C enquête 0 5 , 7 9557 - 15 CAN • 00 € 0 MLSMLS 8 , 3 ISSN | UN MONDE DIN 8 BEL/LUX • NOUVEAU € TUN • 4 € p. 40 4 ANT • REU € • 0 € 8 , 0 3 9 , 4 ALL | CONT BENZEMABENZEMA PORT • MAD francefootball.fr 39 | e é MAR • € ann e 0 8 , 74 3 | ITA «Je kiffemavie» • 797 «Je kiffemavie» € 3 ° 0 n 9 , | 4 19 GR • 20 «JE PEUX JOUER MON VRAI FOOTBALL» ll ««QUQUANDAND J’ENTRAISJ’ENTRAIS SURSUR LELE TERRAIN,TERRAIN, £ 0 5 , vrier JE CHERCHAIS SANS CESSE CRISTIANO RONALDO» l «JE ME SENS BEAUCOUP 3 JE CHERCHAIS SANS CESSE CRISTIANO RONALDO» l «JE ME SENS BEAUCOUP é f GB • 26 PLUS lÉGITIME» l «J’AI L’IMPRESSION DÉSORMAIS DE VOLER» € PLUS lÉGITIME» l «J’AI L’IMPRESSION DÉSORMAIS DE VOLER» 0 8 , 3 mardi p. 10 | € 0 5 , 3 ESP/AND numérique abonnés merci vous êtes aujourd’hui 200 000 abonnés à L’Équipe numérique le portefeuille d’abonnés L’Équipe numérique a franchi le cap des 200 000 le 17 janvier 2019 n° 3797 3 france football 26.02.19 Sommaire Édito 4 zone mixte 8 Les 10... familles de footeux (2) l’invité Karim et Kylian 10Karim Benzema: «Maintenant, c'est moi le leader de l'attaque» éclairage Onzeans les séparent. Mais aussi une image, des attitudes, une réputation, des statistiques. -

Blanc Sur Un Champ De Ruines Taille La Reconstruction Des Bleus S’Annonce Longue Et Incertaine

LE JOURNAL DU DIMANCHE - 05/09/2010 - N° 3321 5 septembre 2010 FOOTBALL 23 Avenir Abidal Blanc sur un champ de ruines taille La reconstruction des Bleus s’annonce longue et incertaine. « On peut ne jamais y arriver », a prévenu hier le sélectionneur Bachelot La reconstruction peut prendre des mois. des champions. Tout est à reconstruire ! Olivier Joly On peut aussi ne jamais y arriver. » On en a pour quatre ans », a estimé Elie Le sélectionneur a pris le temps de re- Baup sur I-Télé. Seul survivant de la « CE N’EST PAS un secret, le niveau de voir la rencontre dans son intégralité avec Coupe du monde 2006 aligné vendredi, Ma- l’équipe de France a baissé. Le classement ses adjoints. Sa nuit a été courte. « J’espé- louda opine : « J’ai commencé par une fi- Fifa le montre bien: on dégringole. » Capi- rais qu’à cinq heures du matin, ils arrive- nale de Coupe du monde, mais les qualifi- taine d’un soir au Stade de France, Florent raient à marquer. Mais non, le score n’a cations et le premier tour avaient été durs. Malouda a donné le ton, hier à Clairefon- pas changé… » La boutade cache une réa- A un moment donné, il faut savoir se révé- taine, au lendemain de la défaite face au lité. L’équipe de France est devenue terri- ler, montrer son caractère. Et surtout ne NON SÉLECTIONNÉ par Bélarus (0-1). Ce fameux classement mon- blement inoffensive. Elle a marqué cinq pas tomber dans la facilité en se disant Laurent Blanc, Eric Abidal re- dial (21e), où l’équipe de France va bientôt buts en neuf matches en 2010, concédé six que ça va être comme ça à chaque fois. -

Le Journal Médical De La Fédération Francaise De Football Décembre 2007

medifoot N°11:medifoot N°10 4/12/07 10:22 Page 1 11 MédiFOOT LE JOURNAL MÉDICAL DE LA FÉDÉRATION FRANCAISE DE FOOTBALL DÉCEMBRE 2007 g g Le double surclassement des PAGE Manipulations 8 jeunes joueurs en équipes seniors vertébrales PAGE 4 g PAGE g La cheville du 10 Histoire de la SMATSH sportif en croissance PAGE 6 g Fluor ingéré, fluorose g Les lésions et sport ostéochondrales du talus PAGE PAGE 9 12 g Fractures de fatigue g du pied du footballeur Infos PAGE PAGE 13 14 medifoot N°11:medifoot N°10 4/12/07 10:22 Page 2 PAGE Editorial 2 DOCTEUR JACQUES LIENARD a création d'un Minis- le président (ou son représentant), cenciés et prennent à cet effet les ou catégories de licenciés, la fédé- Un projet de règlement médical tère de la santé, de la le directeur technique national (ou dispositions nécessaires. ration a la possibilité d'habiliter cer- fédéral reprend un certain nom- jeunesse et des son représentant) et le médecin tains médecins aux compétences et bre d'orientations concernant la sports a conduit Ma- fédéral national. PLUSIEURS THÈMES ONT ÉTÉ ABORDÉS : qualifications particulières. médecine fédérale, la commis- L dame LAURENT, Di- La réunion à laquelle le football sion médicale nationale, le rôle et rectrice des Sports à organiser était invité regroupait une ving- Le certificat médical de non- Le suivi médical règlementaire les missions des différents interve- des réunions de regroupement sur taine de fédérations dont notam- contre-indication à une pratique des sportifs de haut niveau et nants médicaux. Le rôle du (des) le thème "Santé et Fédérations ment celles du rugby, du basket- sportive est indispensable pour la des sportifs en filière d'accès au médecin(s) élu(s) dans les diffé- Sportives" dans le cadre de la dé- ball, du hand-ball, du volley-ball, compétition. -

Les Bleus and Black: a Football Elegy to French Colorblindness

Essay Les Bleus and Black: A Football Elegy to French Colorblindness Khaled A. Beydoun† “If I score, I’m French. If I don’t, I’m an Arab.” - Karim Benzema, French footballer1 “There is no room for the word ‘race’ in the Republic.” - François Hollande, the 24th President of France2 INTRODUCTION In 1998, the chiseled face of the French football team’s tal- isman, Zinedine Zidane, was illuminated on the Arc de Tri- omphe. An endless sea of French men, women and youth of all races flooded the Champs Elysee, screaming in unison, “Zizou for President! Zizou for President!” lauding an Algerian man who rose from the ghettoes of Marseille to become the most beloved † Associate Professor of Law, University of Arkansas-Fayetteville School of Law; Senior Affiliated Faculty, University of California at Berkeley, Islam- ophobia Research & Documentation Project (IRDP); and author of American Is- lamophobia: Understanding the Roots and Rise of Fear (University of California Press, 2018). 1. Rabih Alameddine, Just How Good Would France Be if Every French- Born Arabs Opted to Play for Les Bleus?, THE NEW REPUBLIC (Jun. 23, 2014), https://newrepublic.com/article/118315/what-if-all-french-born-arabs-opted- play-les-bleus. 2. Hollande Propose de Supprimer le mot “Race” dans la Constution, LE MONDE (Nov. 3, 2012), https://www.lemonde.fr/election-presidentielle-2012/ article/2012/03/11/hollande-propose-de-supprimer-le-mot-race-dans-la -constitution_1656110_1471069.html. 20 2018] LES BLEUS AND BLACK 21 man in France.3 A cast of racially and ethnically diverse French- man, led by Zidane, had delivered colorblind France its first World Cup trophy.4 Twenty years after France claimed its first title, a team widely embraced as the “last standing African team in the World Cup,”5 placed a second star atop the Gallic rooster emblazoned on the iconic French jersey. -

Septembre 2019

LE PREMIER MAGAZINE DE SOCCER AU QUÉBEC VOL.41 - No 6 - SEPTEMBRE 2019 BACARY SAGNA LA CULTURE DU HAUT NIVEAU UN MOIS INSENSÉ À L’IMPACT DE MONTRÉAL MARINETTE PICHON CHOISIT LE QUÉBEC ENDUROLYTE XL Produit de performance qui contribue à la fonction musculaire, à l’hydratation et à l’équilibre du pH. Contient du D-Ribose, de l’extrait de betterave et des électrolytestels que le calcium, le potassium, le magnésium et le sodium. SANS OGM SAVEUR DE CERISE 30 PORTIONS 100% sans herbicides, pesticides ou autres produits chimiques. Impact de Montréal UN « DRAMA » TOUS LES TROIS JOURS… 10 L’Impact de Montréal a vécu un mois d’août insensé en coulisses et sur le terrain. Arrivées et départs de joueurs majeurs, renvoi d’entraîneur, rumeurs de nomination d’un directeur sportif, départ d’un personnage historique du club, grogne du stade… tout s’est enchaîné de façon invraisemblable. Retour sur une période trouble. D’un bord de l’océan à l’autre BACARY SAGNA : LA CULTURE DU HAUT NIVEAU... 12 Il fut un temps où l’Europe était considérée comme l’eldorado des Le défenseurSOMMAIRE à la carrière exceptionnelle se livre sur l’Impact de Montréal, la MLS, mais aussi Auxerre, Guardiola, Éditeur – Fondateur : Pasquale Cifarelli l’exigence et l’humilité que requiert le très haut niveau. joueurs de soccer. Meilleurs championnats, meilleure exposition, meil- Éditorialiste : Georges Schwartz leur salaire, meilleurs entraîneurs, tout y était plus beau, plus rose. Rédacteur en chef : Quentin Parisis MLS Conseiller éditorial : Matthias Van Halst Est-ce toujours le cas ? Vraisemblablement, il ne faut pas se mentir. -

Pilgrims Pour Into Makkah Undeterred by MERS Fears

SUBSCRIPTION SATURDAY, JUNE 7, 2014 SHAABAN 9, 1435 AH No: 16189 World leaders Robot makes FIFA’s Blatter mark D-Day in friends on first ducks Qatar Ukraine7 shadow day31 at work re-vote43 calls Pilgrims pour into Makkah undeterred by MERS fears Max 46º 150 Fils Saudi Arabia’s MERS death toll hits 284 Min 32º MAKKAH: Muslim pilgrims from around the world are pouring into the holy city of Makkah in Saudi Arabia, undeterred by the spread of the MERS virus which has killed 284 people in the kingdom. The mysterious Middle East Respiratory Syndrome is considered a deadlier but less transmissible cousin of the SARS virus that appeared in Asia in 2003 and infected 8,273 people, nine percent of whom died. MERS first appeared in Saudi Arabia in April 2012, and the kingdom remains the worst-hit country, accounting for the bulk of a global death toll. But the faithful who dream of visiting the holy shrines in dina at least once in their lives continue toشMakkah and M pour into Makkah to perform the lesser umrah pilgrimage. “We have received warnings by authorities in our country about MERS and were informed of the importance of taking precautions,” said 45-year-old Abdullah, a pilgrim from Malaysia. Wearing a mask, Abdullah said he applies disinfec- tants as he enters the Grand Mosque in Makkah. “God will pro- tect me,” he said. More pilgrims are expected to arrive with the approach of the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan, which starts late in June, and sees hundreds of thousands descend on Makkah for umrah. -

SOCCERNOMICS NEW YORK TIMES Bestseller International Bestseller

4color process, CMYK matte lamination + spot gloss (p.2) + emboss (p.3) SPORTS/SOCCER SOCCERNOMICS NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLER “As an avid fan of the game and a fi rm believer in the power that such objective namEd onE oF thE “bEst booKs oF thE yEar” BY GUARDIAN, SLATE, analysis can bring to sports, I was captivated by this book. Soccernomics is an FINANCIAL TIMES, INDEPENDENT (UK), AND BLOOMBERG NEWS absolute must-read.” —BillY BEANE, General Manager of the Oakland A’s SOCCERNOMICS pioneers a new way of looking at soccer through meticulous, empirical analysis and incisive, witty commentary. The San Francisco Chronicle describes it as “the most intelligent book ever written about soccer.” This World Cup edition features new material, including a provocative examination of how soccer SOCCERNOMICS clubs might actually start making profi ts, why that’s undesirable, and how soccer’s never had it so good. WHY ENGLAND LOSES, WHY SPAIN, GERMANY, “read this book.” —New York Times AND BRAZIL WIN, AND WHY THE US, JAPAN, aUstralia– AND EVEN IRAQ–ARE DESTINED “gripping and essential.” —Slate “ Quite magnificent. A sort of Freakonomics TO BECOME THE kings of the world’s for soccer.” —JONATHAN WILSON, Guardian MOST POPULAR SPORT STEFAN SZYMANSKI STEFAN SIMON KUPER SIMON kupER is one of the world’s leading writers on soccer. The winner of the William Hill Prize for sports book of the year in Britain, Kuper writes a weekly column for the Financial Times. He lives in Paris, France. StEfaN SzyMaNSkI is the Stephen J. Galetti Collegiate Professor of Sport Management at the University of Michigan’s School of Kinesiology. -

The Technician 38•E 14.1.2008 12:06 Page 1

The Technician 38•E 14.1.2008 12:06 Page 1 Including Editorial: Lucky for Some Interview: Morten Olsen Better Coaches = Better Players Elite Youth Football – The Next Steps From Meridian to Champions League Benches and Benchmarks NEWSLETTER FOR COACHES N O .38 FEBRUARY 2008 The Technician 38•E 14.1.2008 12:06 Page 2 IMPRESSUM EDITORIAL GROUP Andy Roxburgh Graham Turner Frits Ahlstrøm PRODUCTION André Vieli Dominique Maurer Atema Communication SA Printed by Cavin SA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Hélène Fors Sylvain Wiltord wearing the number 13 shirt in the EURO 2000 final against Italy. COVER Having already met in the qualifiers, France and Italy find themselves in the same group for the EURO 2008 final round. Also in the same situation are Romania and the Netherlands, and Spain and Sweden. (Photo: Meyer/AFP/Getty Images) PA ARCHIVES/PAPA PHOTOS 2 The Technician 38•E 14.1.2008 12:06 Page 3 LUCKY FOR SOME EDITORIAL us an indication of things to come finalist with Portugal in 2004, who as we contemplate the forthcoming has the passion and know-how to cre- BY ANDY ROXBURGH, European Championship finals. For ate another stir. Köbi Kuhn of Switzer- UEFA TECHNICAL DIRECTOR instance, Germany set the benchmark land, Lars Lagerbäck of Sweden, and for strikes at goal during the qualifiers, Karel Brückner of the Czech Republic, with 146 efforts resulting in 35 goals, veterans of EURO 2004, are all gurus and this included a record scoreline of the technical area and know what for Joachim Löw’s side away to San it takes to succeed – without the use Marino.