Rethinking Anglo-Saxon Shrines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fully Subsidised Services Comments Roberts 120 • Only Service That

167 APPENDIX I INFORMAL CONSULTATION RESPONSES County Council Comments - Fully Subsidised Services Roberts 120 • Only service that goes to Bradgate Park • Service needed by elderly people in Newtown Linford and Stanton under Bardon who would be completely isolated if removed • Bus service also used by elderly in Markfield Court (Retirement Village) and removal will isolate and limit independence of residents • Provides link for villagers to amenities • No other bus service between Anstey and Markfield • Many service users in villages cannot drive and/or do not have a car • Service also used to visit friends, family and relatives • Walking from the main A511 is highly inconvenient and unsafe • Bus service to Ratby Lane enables many vulnerable people to benefit educational, social and religious activities • Many residents both young and old depend on the service for work; further education as well as other daily activities which can’t be done in small rural villages; to lose this service would have a detrimental impact on many residents • Markfield Nursing Care Home will continue to provide care for people with neuro disabilities and Roberts 120 will be used by staff, residents and visitors • Service is vital for residents of Markfield Court Retirement Village for retaining independence, shopping, visiting friends/relatives and medical appointments • Pressure on parking in Newtown Linford already considerable and removing service will be detrimental to non-drivers in village and scheme which will encourage more people to use service Centrebus -

Leicestershire. Galby

DIRECTORY.] LEICESTERSHIRE. GALBY. 83 FROLESWORTH (or Frowlesworlh) is a pleasant from designs by William Bassett Smitb esq. of London, village and parish, 2 miles north from Gllesthorpe station and in 1895 the tower was restored and battlementa and 3 south-west from Broughton Astley station, botb added: the church affords 160 sittings. The register on the Midland railway, 4 west from Ashby Magna dates from the year 1538 and is almost complete. The station, on the main line of the Great Central railway, living is a rectory, net yearly value £290, with residence 4) south-east from Hinckley, 5 north-west from and 57 acres of glebe, in the gift of truste es of the Lutterworth and 92 from London, in the Southern late Rev. Alfred Francis Boucher M.A. and held since division of the county, Guthlaxton hundred, petty 1886 by the Rev. Charles Estcourt Boncher M.A. of sessional division, union and county court district, Trinity Hall, Cambridge, rural dean of Guthlaxton second, of Lutterworth, rural deanery of Guthlaxton (second and master of Smith's ~ almshouses (income £30). Here are portion), archdeaconry of Leicester and diocese of Peter· twenty-four almshouses for widows of the communion of borough. The church of St. Nicholas is a building of the Church of England,founded in 1726 under the will of Chief stone, in the Decorated and Perpendicular styles, with Baron Smith, mentioned abo,·e; the income is now £630 some Early English remains, and consists of chancel, yearly, and each inmate receives £20 yearly: attached to nave, aisles, north porch and a western tower of the the almshouses is a little chapel, in which divine service Decorated period with crocketed pinnacles and contain- is conducted once a week by the rector, who is master of the ing 3 bells, two of which are dated 1638 and 1'749 re- foundation. -

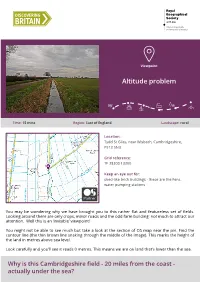

Altitude Problem

Viewpoint Altitude problem Time: 15 mins Region: East of England Landscape: rural Location: Tydd St Giles, near Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, PE13 5NU Grid reference: TF 38300 13300 Keep an eye out for: shed-like brick buildings - these are the Fens water pumping stations You may be wondering why we have brought you to this rather flat and featureless set of fields. Looking around there are only crops, minor roads and the odd farm building: not much to attract our attention. Well this is an ‘invisible’ viewpoint! You might not be able to see much but take a look at the section of OS map near the pin. Find the contour line (the thin brown line snaking through the middle of the image). This marks the height of the land in metres above sea level. Look carefully and you’ll see it reads 0 metres. This means we are on land that’s lower than the sea. Why is this Cambridgeshire field - 20 miles from the coast - actually under the sea? The answer is all around. Look for the long straight channels across the fields. In wet weather they are full of water. These are not natural rivers but artificial ditches, dug to drain water off the fields. So much water was drained away here that the soil dried out and shrank. This lowered the land so much that in places it is now below sea-level! But why was the land drained here and how? Originally the expanse of low-lying land from Cambridge through The Wash and up into Lincolnshire was inhospitable. -

Ashby Folville Lodge Folville Street | Ashby Folville | Melton Mowbray | Leicestershire | LE14 2TE

Ashby Folville Lodge Folville Street | Ashby Folville | Melton Mowbray | Leicestershire | LE14 2TE YOUR PROPERTY EXPERTS Property at a Glance Situated within approximately 5.7 acres of gardens and parkland on the very edge of this highly desirable village, a substantial six bedroom detached family home of impressive proportions and Substantial Six Bedroom Extended Former Gate Lodge offering four reception rooms and four bathrooms. With a magnificent gated approach, the property was the former gate Energy Rating Pending lodge to Ashby Folville Manor and has been substantially extended over the years and is currently designed to 1.1 Acres of Gardens and Grounds accommodation disabled access with living care through the addition of a self contained annexe and separate living 4.6 Acres of Adjacent Parkland/Paddock accommodation. Requiring general upgrading and modernisation, the property has spectacular views over adjacent Four Reception Rooms parkland, former heated swimming pool and large double garage. Four Bathrooms Large Ground Floor Bedrooms Suite Self Contained Apartment Garaging for Three/Four Vehicles Magnificent Views over Parkland Highly Desirable Village Requiring General Upgrading/Modernisation Potential for One Large Dwelling or to Create Two (Subject to Planning) Offers Over: £600,000 The Property Inner Reception Hall Ashby Folville Lodge is a substantial property in an outstanding rural setting. Originally 17'11" x 10'10" (5.46m x 3.3m) the former gate lodge to Ashby Folville Manor, the property has been substantially With attractive parquet flooring, multi fuel stove with brick surround, stairs to first floor, extended at least twice over the years to create an impressive family home. -

ASHBY FOLVILLE to THURCASTON: the ARCHAEOLOGY of a LEICESTERSHIRE PIPELINE PART 2: IRON AGE and ROMAN SITES Richard Moore

230487 01c-001-062 18/10/09 09:14 Page 1 ASHBY FOLVILLE TO THURCASTON: THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF A LEICESTERSHIRE PIPELINE PART 2: IRON AGE AND ROMAN SITES Richard Moore with specialist contributions from: Ruth Leary, Margaret Ward, Alan Vince, James Rackham, Maisie Taylor, Jennifer Wood, Rose Nicholson, Hilary Major and Peter Northover illustrations by: Dave Watt and Julian Sleap Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, Roman and early Anglo-Saxon remains were excavated and recorded during construction of the Ashby Folville to Thurcaston gas pipeline. The earlier prehistoric sites were described in the first part of this article; this part covers three sites with Roman remains, two of which also had evidence of Iron Age activity. These two sites, between Gaddesby and Queniborough, both had linear features and pits; the more westerly of the two also had evidence of a trackway and a single inhumation burial. The third site, between Rearsby and East Goscote, was particularly notable as it contained a 7m-deep stone-lined Roman well, which was fully excavated. INTRODUCTION Network Archaeology Limited carried out a staged programme of archaeological fieldwork between autumn 2004 and summer 2005 on the route of a new natural gas pipeline, constructed by Murphy Pipelines Ltd for National Grid. The 18-inch (450mm) diameter pipe connects above-ground installations at Ashby Folville (NGR 470311 312257) and Thurcaston (NGR 457917 310535). The topography and geology of the area and a description of the work undertaken were outlined in part 1 of this article (Moore 2008), which covered three sites with largely prehistoric remains, sites 10, 11 and 12. -

Download (11MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] "THE TRIBE OF DAN": The New Connexion of General Baptists 1770 -1891 A study in the transition from revival movement to established denomination. A Dissertation Presented to Glasgow University Faculty of Divinity In Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Frank W . Rinaldi 1996 ProQuest Number: 10392300 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10392300 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. -

New Holme Farm, Wysall Lane, Keyworth, Nottingham £1,500,000

New Holme Farm, Wysall Lane, Keyworth, Nottingham £1,500,000 New Holme Farm, Property Description Our View Holme Farm occupies a spectacular position in one of the The property is approached via electrically operated gates Wysall Lane, Keyworth, most sought after and superbly accessible locations in the opening onto a driveway that sweeps around to the rural Nottinghamshire, set on the hillside with stunning parking area. The main house has a hearty sense of family Nottingham viewings over the city. In addition to the main house and brings the modern architecture and the rural grounds there are Equestrian facilities comprising of; a stable block together. Consisting of; four large suite bedrooms with housing five stables, feed store and tack room, paddocks, two ensuites and a plush family bathroom. The kitchen is £1,500,000 horse exerciser, an indoor school area and an outdoor area the heart of the house with a huge entertaining space and suitable for a manege. Outbuildings There are a number a country shaker style made from solid oak. The finishing of large constructed outbuildings suitable for a range of touches have been applied throughout to signify quality alternative uses (subject to planning consent). The house with solid oak doors and marble porcelanosa tiles in the and the outbuildings were built on 2004. Grounds grand family bathroom. Through every aspect, from every extending to six acres, the gardens and grounds surround bedroom of the first floor you are surrounded by the wrap the main house and complement it perfectly. around panoramic views. EPC GRADE D Location For full EPC please contact the branch Set in the rolling countryside of rural Notinghamshire on the outskirts of the City, this property is situated within Keyworth which is a highly sought after village. -

East Midlands

Archaeological Investigations Project 2005 Building Survey East Midlands Derby Derby (G.56.496) SK35003650 {76D619AD-4288-4013-8AEE-77F82CA7876E} Parish: Derby Postal Code: DE1 3GU CONNECTING DERBY Connecting Derby Driver, L & Hislop, M Birmingham : Birmingham Artchaeology, 2005, 85pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Birmingham Archaeology Archaeological periods represented: MO, PM Derbyshire Amber Valley (G.17.497) SK40205128 {6283A264-AD1E-4A30-BAC6-215B8D0FA53E} Parish: Ripley Postal Code: DE5 3BD THE BUTTERLEY WORKS A Report on Building Recording at the Butterley Works, Ripley, Derbyshire Slatcher, D Newark : John Samuels Archaeological Consultants, 2005, 47pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: John Samuels Archaeological Consultants Archaeological periods represented: PM, MO Bolsover (G.17.498) SK49157543 {DAD2F7A8-D838-4F43-87E2-0626649D784F} Parish: Clowne Postal Code: S43 4RS CLOWNE STANDING CROSS A Monument Recording Survey of Clowne Standing Cross, Derbyshire Sheppard, R Nottingham : Trent & Peak Archaeological Unit, 2005, 35pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Trent & Peak Archaeological Unit SMR primary record number: 865 Archaeological periods represented: PM Chesterfield (G.17.499) SK36707730 {71126E4E-3E47-48E4-A9D0-69DB98A2A5F3} Parish: Dronfield Postal Code: S18 4AQ DRONFIELD HALL BARN Dronfield Hall Barn, High Street, Dronfield Jones, S Dronfield : Jones, S, 2005, 8pp, figs, refs Work undertaken by: Jones, S SMR primary record number: 882 Archaeological periods represented: -

Sustainability Appraisal (SA) / Strategic

Leicestershire Minerals Development Framework: Site Allocations DPD (Preferred Options) Sustainability Appraisal (SA) / Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Sustainability Appraisal Report (Appendices) June 2006 Prepared for Leicestershire County Council by: Atkins Ltd Axis 6 th Floor West 10 Holliday St Birmingham B1 1TF Tel: Nicki Schiessel 0121 483 5986 Email: [email protected] This document is copyright and should not be copied in whole or in part by any means other than with the approval of Atkins Consultants Limited. Any unauthorised user of the document shall be responsible for all liabilities arising out of such use. Leicestershire Minerals Development Framework Site Allocations DPD Sustainability Appraisal Report Appendices Contents Section Page Appendix A: List of Consultees and Interested Stakeholders 1 Appendix B: Summary of the Consultation Responses on the Scoping Report 15 Appendix C: Baseline Tables 23 Appendix D: Assessment of Proposed Sites 38 Leicestershire Minerals Development Framework Site Allocations DPD Sustainability Appraisal Report Appendices APPENDIX A: LIST OF CONSULTEES AND INTERESTED STAKEHOLDERS 1 Leicestershire Minerals Development Framework Site Allocations DPD Sustainability Appraisal Report Appendices SPECIFIC CONSULTATION BODIES GENERAL: East Midlands Regional Assembly Highways Agency, Melton Mowbray Programme Planning & Development, Birmingham Countryside Agency, East Midlands Region, East Midlands Development Agency Nottingham Nottingham Environment Agency, Leicestershire Partnership -

863 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

863 bus time schedule & line map 863 Keyworth - East Leake - Ruddington View In Website Mode The 863 bus line (Keyworth - East Leake - Ruddington) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) East Leake: 2:46 PM (2) Keyworth: 9:40 AM - 1:40 PM (3) Ruddington: 10:46 AM - 12:46 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 863 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 863 bus arriving. Direction: East Leake 863 bus Time Schedule 25 stops East Leake Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 2:46 PM The Square, Keyworth The Square, Keyworth Civil Parish Tuesday 2:46 PM Health Centre, Keyworth Wednesday 2:46 PM Woodleigh, Keyworth Civil Parish Thursday 2:46 PM West Close, Keyworth Friday 2:46 PM Manor Road, Keyworth Civil Parish Saturday 2:46 PM Croft Road, Keyworth Manor Road, Keyworth Civil Parish Spinney Road, Keyworth 863 bus Info Nottingham Road, Keyworth Direction: East Leake 100-102 Nottingham Road, Keyworth Civil Parish Stops: 25 Trip Duration: 29 min Normanton Lane, Keyworth Line Summary: The Square, Keyworth, Health Normanton Lane, Keyworth Civil Parish Centre, Keyworth, West Close, Keyworth, Croft Road, Keyworth, Spinney Road, Keyworth, Nottingham Platt Lane, Keyworth Road, Keyworth, Normanton Lane, Keyworth, Platt Nicker Hill, Keyworth Civil Parish Lane, Keyworth, Covert Close, Keyworth, Lyncombe Gardens, Keyworth, Shops, Keyworth, Fairway, Covert Close, Keyworth Keyworth, Rowan Drive, Keyworth, Maple Close, Keyworth, Willow Brook School, Keyworth, Lyncombe Gardens, Keyworth Willoughby -

Langtons' and District Newsletter

Langtons’ and District Newsletter Spring Edition 2020 February Fill Dyke An old saying goes, "February fill dyke, be black or be it white; Be it white, 'tis better to like." This roughly means that rain and snow are both welcome in February, although snow is preferable. Well it’s certainly been black this year. Harborough District Council are encouraging parish councils to put in place Community Response Plans in the event of an incident such as severe weather. Tur Langton Parish Council has theirs and East Langton Parish Council’s is nearly completed (see p 7). The plan provides a guide as to how and where the local community may support the Emergency services in terms of information and providing predetermined resources where appropriate. Let’s hope we never have to use it. Keep safe. Roz Folwell Stonton Wyville taken by G. Devereaux-Batchelor Printed by Omniprint, Market Harborough 1 2 Church Langton CE (AIDED) Primary School Young Voices The pupils in years five and six were very fortunate to have the opportunity to perform as part of a six thousand strong choir at the Young Voices concert at the Birmingham Arena. Supported by a very keen team of teachers, the children sang with a wide range of acts including Tony Hadley and alongside street dance group Urban Sounds. This is part of our ongoing opportunities for the pupils to take part in musical performances to different audiences. As part of the Spark Festival, a celebration of the arts taking place in Leicester during February, we were delighted to welcome an IndoJazz band to perform to the children. -

Fenland District Wide Local Plan Tydd Gote ______

Fenland District Wide Local Plan Tydd Gote _______________________________________________________________________________________ TYDD GOTE Inset Proposals Map No 24 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. This statement contains detailed planning proposals for the area of Tydd Gote within Cambridgeshire. It must be read in conjunction with the general policies set out in Part One of the Local Plan which apply throughout the District. 2. LOCATION 2.1. The village of Tydd Gote is situated 7 miles north of Wisbech, and 2 miles east of Tydd St Giles on the A1101. The majority of the village is in Lincolnshire. 3. POPULATION 3.1. The population of Tydd Gote has remained stable at 80 from 1981 to the present. 3.2. In mid 1990 the housing stock numbered some 20 dwellings. 3.3. Between mid 1986 and mid 1990 there were 3 housing completions in Tydd Gote. 4. SERVICES AND FACILITIES 4.1. Apart from the Tydd Gote public house all services and facilities lie in the Lincolnshire part of the village. There is no mains drainage and no surface water system. 5. KEY FEATURES OF FORM AND CHARACTER 5.1. Hannath Road abuts the Tydd Gote Conservation Area which runs along the Lincolnshire side of the County boundary. In common with other settlements in the vicinity of the District, the amount of woodland is unique. This is especially the case along the Hannath Road area of Tydd Gote. The high hedges and mature trees complement some fine buildings. Between Dark Lane and Hannath Road is an attractive open field enclosed by some splendid mature trees. Tree Preservation Orders currently protect twenty-six individual trees.