Download (11MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

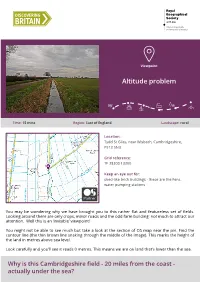

Altitude Problem

Viewpoint Altitude problem Time: 15 mins Region: East of England Landscape: rural Location: Tydd St Giles, near Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, PE13 5NU Grid reference: TF 38300 13300 Keep an eye out for: shed-like brick buildings - these are the Fens water pumping stations You may be wondering why we have brought you to this rather flat and featureless set of fields. Looking around there are only crops, minor roads and the odd farm building: not much to attract our attention. Well this is an ‘invisible’ viewpoint! You might not be able to see much but take a look at the section of OS map near the pin. Find the contour line (the thin brown line snaking through the middle of the image). This marks the height of the land in metres above sea level. Look carefully and you’ll see it reads 0 metres. This means we are on land that’s lower than the sea. Why is this Cambridgeshire field - 20 miles from the coast - actually under the sea? The answer is all around. Look for the long straight channels across the fields. In wet weather they are full of water. These are not natural rivers but artificial ditches, dug to drain water off the fields. So much water was drained away here that the soil dried out and shrank. This lowered the land so much that in places it is now below sea-level! But why was the land drained here and how? Originally the expanse of low-lying land from Cambridge through The Wash and up into Lincolnshire was inhospitable. -

Church, Place and Organization: the Development of the New

238 CHURCH, PLACE AND ORGANIZATION The Development of the New Connexion General Baptists in Lincolnshire, 1770-18911 The history and developm~nt of the New Connexion of· the General Baptists represented a particular response to the challenges which the Evangelical Revival brought to the old dissenting churches. Any analysis of this response has to be aware of three key elements in the life of the Connexion which were a formative part in the way it evolved: the role of the gathered church, the context of the place within which each church worked and the structures which the organization of the Connexion provided. None of them was unique to it, nor did any of them, either individually, or with another, exercise a predominant influence on it, but together they contributed to the definition of a framework of belief, practice and organization which shaped its distinctive development. As such they provide a means of approaching its history. At the heart of the New Connexion lay the gathered churches. In the words of Adam Taylor, writing in the early part of the nineteenth century, they constituted societies 'of faithful men, voluntarily associated to support the interests of religion and enjoy its privilege, according to their own views of these sacred subjects'. 2 These churches worked within the context of the places where they had been established, and this paper is concerned with the development of the New Connexion among the General Baptist churches of Lincolnshire. Moreover, these Lincolnshire churches played a formative role in the establishment of the New Connexion, so that their history points up the partiCUlar character of the relationship between churches and the concept of a connexion as it evolved within the General Baptist community. -

The Good Time Coming : the Impact of William Booth's Eschatological Vision

.. ....... .. I. ... ., ... : .. , . j;. ..... .. .... The Copyright law of the United States (title 17, United States Code) governs the making of phwtmwpies or derreproductiwns of mpyrighted material. Under cetZBin conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorid to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. Om of these specific mditions is that the phohmpy or reproduction is not to be “Used fir my purpose other than private study, schdanhip, or research.” If B user make3 a quest far, or later uses, a photompy or repductim for puqmses in ecess of ‘‘fair we9”that user may be liable for mpyright infringement, This institution reserves the right to rehe to accept a copying order if, in its judgmenk fulfitlrnent of the order would involve violation ofcoMght Jaw- By the using this materid, you are couwnting h abide by this copyright policy, Any duplication, reprodndinn, nr modification of this material without express waitken consent from Asbuv Theological Seminary andhr the original publisher is prohibited. Q Asbury TheoIogi@alSeminary 2009 MECUMTAW BINDERY, INC ASBURY SEMINARY 10741 04206 ASBURY THEOLOGICAL, SEMINARY “THE GOOD TZME COMING”: THE IMPACT OF WILLIAM BOOTH’S ESCHATOLOGICAL VISION A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUlREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE, MASTOR OF DIVINITY BY ANDREW S. MILLER I11 WILMORE, KY DECEMBER 1,2005 “THE GOOD TIME COMING”: THE IMPACT OF WILLIAM BOOTH’S ESCHATOLOGICAL VISION Approved by: Date Accepted: Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost Date CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................... V INTRODUCTION ...................................... 1 Goals of the Study Review of Literature Chapter : 1. WILLIAM BOOTH’S ESCHATOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE .... 6 Eschatology as the Centerpiece of William Booth’s Theology William Booth as a Postmillennialist William Booth’s Theological History The Making of an Eschatological Army Contemporary Application Conclusion 2. -

A Visitor's Guide to Barton in Fabis

A Visitor’s Guide to Barton in Fabis Contents STONE AGE BARTON ............................................................................. 2 THE ANCIENT BRITONS' HILL ................................................................. 2 THE ROMAN LEGACY ............................................................................. 2 BARTON IN THE BEANS ......................................................................... 3 GARBYTHORPE - HOME OF THE VIKINGS? ................................................ 3 13TH CENTURY MURDER ........................................................................ 3 FIRE, FLOOD and a PIG IN THE CHURCHYARD! ......................................... 4 PAST LORDS OF BARTON MANOR ............................................................ 5 THE DOVECOTE .................................................................................... 6 BARTON GYPSUM .................................................................................. 6 BARTON ON BROADWAY! ....................................................................... 7 A KING RIDES BY .................................................................................. 7 WORKING THE LAND ............................................................................. 7 THAT FAMOUS CHEESE .......................................................................... 8 FROM TAVERNS TO TEA-HOUSES VIA BARTON FERRY ............................... 9 HOWZAT .............................................................................................. 9 THE VILLAGE -

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY SOCIETY (incorporating the Congregational Historical Society, founded in 1899, and the Presbyterian Historical Society of England, founded in 1913). EDITOR; Dr. CLYDE BINFIELD, M.A., F.S.A. Volume 6 No 2 May 1998 CONTENTS Editorial . 69 Notes . 70 Ian Sellers (1931-1997) by John Munsey Turner. 71 Nursed by the Church: The Founding of the Congregational Schools by Alan Argent .............................. : . ·72 A Learned and Gifted Protestant Minister:John Seldon Whale, 19 December 1896- 17 September 1997 by Clyde Binfield . 97 Reformed or United? Twenty-five Years of the United Reformed Church by David M. Thompson . 131 Reviews by David Hilborn, Robert Pope, Alan P.F. Sell, Roger Tomes . and Clyde Binfield. 144 Some Contemporaries (1996) by Alan P.F. Sell.................... 151 Bunhill Fielders by Brian Louis Pearce . Inside back cover EDITORIAL This issue has an educational aspect. Each year Reports to Assembly include reports from six schools - Caterham, Eltham College, Silcoates, Taunton, Walthamstow Hall, and Wentworth College (as it is now called). That these are not the sum total of Congregationalism's contribution to independent education is made clear in Alan Argent's article. Although links with the United Reformed Church are now slender (they might be described as pleasant but formal), origins cannot be wished away. In the past year Taunton and Wentworth College have produced attractive histories. The current General Secretary of the United Reformed Church is an Old Silcoatian; an investigative journalist noted, in the course of the last election, that the wives of Paddy Ashdown, the late Harold Wilson, and Neil Hamilton, were past pupils of Wentworth Milton Mount. -

Denominations Andministries

THE ESSENTIAL HANDBOOK OF DENOMINATIONS AND MINISTRIES GEORGE THOMAS KURIAN AND SARAH CLAUDINE DAY, EDITORS C George Thomas Kurian and Sarah Claudine Day, eds., The Essential Handbook of Denominations and Ministries Baker Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2017. Used by permission. _Kurian-Day_BakerHandbook_JK_bb.indd 3 11/18/16 11:16 AM These websites are hyperlinked. www.bakerpublishinggroup.com www.bakeracademic.com © 2017 by George Thomas Kurian www.brazospress.com Published by Baker Books www.chosenbooks.com a division of Baker Publishing Group P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287 www.revellbooks.com http://www.bakerbooks.com www.bethanyhouse.com Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kurian, George Thomas, editor. Title: The essential handbook of denominations and ministries / George Thomas Kurian and Sarah Claudine Day, editors. Description: Grand Rapids : Baker Books, 2017. Identifiers: LCCN 2016012033 | ISBN 9780801013249 (cloth) Subjects: LCSH: Christian sects. Classification: LCC BR157 .E87 2017 | DDC 280.0973—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016012033 Scripture quotations labeled ASV are from the American Standard Version of the Bible. Scripture quotations labeled KJV are from the King James Version of the Bible. Scripture quotations labeled NASB are from the New American Standard Bible®, copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. -

Richard Cobden, Educationist, Economist

RICHARD COBDEN, EDUCATIONIST, ECONOMIST AND STATESMAN. BY PETER NELSON FARRAR M.A. (oxoN), M.A. (LVPL). THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD. Division of Education, June 1987. ii CONTENTS Page Ref. Summary iv Abbreviations vi Photographs vii Preface and Acknowledgements viii Part I. An Analysis of Cobden's Ideas and the Formative Influences. Chapter 1. An introductory analysis of Cobden's social philosophy and political activities. 1, 18 2. Cobden's character and formative years. 21, 39 3. Cobden's religious, moral and educa- tional philosophy. 41, 63 4. Cobden's approach to economics. 65, 81 Part II. Thought and Action 1835-1865. 5. The pen of "a Manchester manufacturer". 85, 98 6. Education for the people of Sabden and Chorley. 100, 120 7. Awakening Manchester 1835-1836 123, 147 8. The establishment of the Manchester Society for Promoting National Education. 152, 173 9. Educating the working class: schools and lyceums. 177, 195 10. "The education of 17 millions" the Anti-Corn Law League. 199, 231 11. Cobden and Frederic Bastiat: defining the economics of a consumer society. 238, 264 12. Amid contending ideals of national education 1843-1850. 269, 294 13. Guiding the National Public School Association 1850-1854. 298, 330 14. The Manchester Model Secular School. 336, 353 15. Cobden's last bid for a national education 1855-57. 355, 387 iii Page Ref. 16. The schooling of Richard Cobden junior. 391, 403 17. Newspapers for the millions. 404, 435 18. Investing in a future civilisation: the land development of the Illinois Central Railroad. -

Winter-2008.Pdf

VA OHIO VALLEY J.Blaine Hudson Vice Chairs Judith K.Stein,M.D. HISTORY STAFF University ofLouisville Otto Budig Steven Steinman lane Garvey Merrie Stewart Stillpass Editors R.Douglas Hurt Dee Gettler John M.Tew,Jr.,M.D. Christopher Phillips Purdue University Robert Sullivan James L.Turner DepartnientofHutory At Vontz,III Cincinnati James C. Klotter Treasurer University of Joey D.Williams MarkJ.Hauser Georgetown College Gregory Wolf A.Glenn Crothers Department ofHistory Bruce Levine Secretary THE FILSON University ofLouisville Uniwisity ofIllinois Martine R. Dunn at HISTORICAL Director GfResearch Urbana-Champaign SOCIETY BOARD OF Fbe Fihon Historical Society President and CEO DIRECTORS Harry N. Scheiber Douglass W McDooald Managing Editors UitioersityCalifoi' < nia at President Erin Clephas Berkeley Vice President of 7be Filson Historical Society Museums Orme Wilson,III Steven M. Stowe Tonya M.Matthews Ruby Rogers Indiana University Secretary Cincinnati Mt,3ftim Center David Bohl Margaret Roger D.Tate Cynthia Booth Barr Kulp EditorialAssistant Somerset Community College Stephanie Byrd Treasurer Brian Gebhat John E Cassidy J Walker Stites,m Department ofHistory Joe W.Trotter,Jr. David Davis Edwad D. Diller University ofCincit:,tati Carnegie Mellon University David L.Armstrong Deanna Donnelly J.McCauley Brown Editorial Board Altina Walier James Ellerhorst S.Gordon Dabney Stephen Aron University of Connecticut David E.Foxx Louise Farnsley Gardner Univer:ity ofCatifornia at Richard J.Hidy Holly Gathright LosAngeles CINCINNATI Francine S. Hiltz A.Stewart Lussig, MUSEUM CENTER Ronald A. Koetters 7homas T Noland,Jr. Joan E.Cashin BOARD OF Gary Z.Lindgren Anne Brewer Ogden Obio State Univmity TRUSTEES Kenneth W.Lowe H. Powell Starks Shenan R Murphy Ellen T.Eslinger Chair Robert W.Olson John R Stern William M. -

Rural Grass Cutting III Programme 2021 PDF, 42 Kbopens New Window

ZONE 1 The rural grass cutting takes 6 weeks to complete and is split into 10 zones. The roads surrounding the close by villages and towns fall within Zone 1 DATE RANGE PARISHES WITHIN ZONE 1 30th August - 5th September Primethorpe Broughton Astley Willoughby Waterleys Peatling Magna Ashby Magna Ashby Parva Shearsby Frolesworth Claybrooke Magna Claybrooke Parva Leire Dunton Bassett Ullesthorpe Bitteswell Lutterworth Cotesbach Shawell Catthorpe Swinford South Kilworth Walcote North Kilworth Husbands Bosworth Gilmorton Peatling Parva Bruntingthorpe Upper Bruntingthorpe Kimcote Walton Misterton Arnesby ZONE 2 The rural grass cutting takes 6 weeks to complete and is split into 10 zones. The roads surrounding the close by villages and towns fall within Zone 2 DATE RANGE PARISHES WITHIN ZONE 2 23rd August - 30th August Kibworth Harcourt Kibworth Beauchamp Fleckney Saddington Mowsley Laughton Gumley Foxton Lubenham Theddingworth Newton Harcourt Smeeton Westerby Tur Langton Church Langton East Langton West Langton Thorpe Langton Great Bowden Welham Slawston Cranoe Medbourne Great Easton Drayton Bringhurst Neville Holt Stonton Wyville Great Glen (south) Blaston Horninghold Wistow Kilby ZONE 3 The rural grass cutting takes 6 weeks to complete and is split into 10 zones. The roads surrounding the close by villages and towns fall within Zone 3 DATE RANGE PARISHES WITHIN ZONE 3 16th August - 22nd August Stoughton Houghton on the Hill Billesdon Skeffington Kings Norton Gaulby Tugby East Norton Little Stretton Great Stretton Great Glen (north) Illston the Hill Rolleston Allexton Noseley Burton Overy Carlton Curlieu Shangton Hallaton Stockerston Blaston Goadby Glooston ZONE 4 The rural grass cutting takes 6 weeks to complete and is split into 10 zones. -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES LIBERATION SOCIETY A/LIB Page 1 Reference Description Dates ADMINISTRATION Minutes A/LIB/001 Minute

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 LIBERATION SOCIETY A/LIB Reference Description Dates ADMINISTRATION Minutes A/LIB/001 Minute book [of the committee] of The British Jan 1850 - Anti-State-Church Association; indexed; Nov 1853 marked "Vol. 2" A/LIB/002 Minute book of the Executive Committee of the Nov 1853 - Society for the Liberation of Religion from State Dec 1861 -Patronage and Control; indexed A/LIB/003 Minute book of the Executive Committee of the Jan 1862 - Society for the Liberation of Religion from State Dec 1867 -Patronage and Control; indexed A/LIB/004 Minute book of the Executive Committee of the Jan 1868 - Society for the Liberation of Religion from State Dec 1872 -Patronage and Control; indexed, marked "Vol. V". A/LIB/005 Minute book of the Executive Committee of the Jan 1873 - Jul Society for the Liberation of Religion from State 1877 -Patronage and Control; indexed, marked "Vol. VI". A/LIB/006 Minute book of the Executive Committee of the Sep 1877 - Apr Society for the Liberation of Religion from State 1883 -Patronage and Control; indexed, marked "Vol. VII". A/LIB/007 Minute book of the Executive Committee of the May 1883 - Society for the Liberation of Religion from State Dec 1889 -Patronage and Control; indexed, marked "Vol. VIII". A/LIB/008 Minute book of the Executive Committee of the Jan 1890 - Apr Society for the Liberation of Religion from State 1898 -Patronage and Control; indexed, marked "Vol. IX". A/LIB/009 Minute book of the Executive Committee of the May 1898 - Society for the Liberation of Religion from State Apr 1907 -Patronage and Control; indexed, marked "Vol. -

Baptist History and Distinctives

Baptist History and Distinctives What’s The Big Deal About Being a Baptist? "Ye should earnestly contend for the faith which was once delivered unto the saints." (Jude 1:3) STUDENT EDITION NAME ___________________________________ By Pastor Craig Ledbetter, Th.G., B.A. Part of the Teaching Curriculum of Cork Bible Institute Unit B, Enterprise park Innishmore, Ballincollig, Cork, Ireland +353-21-4871234 [email protected] www.biblebc.com/cbi © 2018 Craig Ledbetter, CBI Baptist History and Distinctives Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 Baptist Ignorance ............................................................................................................ 6 First Century Patterns to Follow ....................................................................................... 9 The Right Kind of Baptist ................................................................................................27 A Brief History of the Baptists .........................................................................................37 Baptists in America .........................................................................................................55 Baptist History Chart ......................................................................................................62 Baptists in Modern Europe ..............................................................................................64 Bibliography ...................................................................................................................66 -

How English Baptists Changed the Early Modern Toleration Debate

RADICALLY [IN]TOLERANT: HOW ENGLISH BAPTISTS CHANGED THE EARLY MODERN TOLERATION DEBATE Caleb Morell Dr. Amy Leonard Dr. Jo Ann Moran Cruz This research was undertaken under the auspices of Georgetown University and was submitted in partial fulfillment for Honors in History at Georgetown University. MAY 2016 I give permission to Lauinger Library to make this thesis available to the public. ABSTRACT The argument of this thesis is that the contrasting visions of church, state, and religious toleration among the Presbyterians, Independents, and Baptists in seventeenth-century England, can best be explained only in terms of their differences over Covenant Theology. That is, their disagreements on the ecclesiological and political levels were rooted in more fundamental disagreements over the nature of and relationship between the biblical covenants. The Baptists developed a Covenant Theology that diverged from the dominant Reformed model of the time in order to justify their practice of believer’s baptism. This precluded the possibility of a national church by making baptism, upon profession of faith, the chief pre- requisite for inclusion in the covenant community of the church. Church membership would be conferred not upon birth but re-birth, thereby severing the links between infant baptism, church membership, and the nation. Furthermore, Baptist Covenant Theology undermined the dominating arguments for state-sponsored religious persecution, which relied upon Old Testament precedents and the laws given to kings of Israel. These practices, the Baptists argued, solely applied to Israel in the Old Testament in a unique way that was not applicable to any other nation. Rather in the New Testament age, Christ has willed for his kingdom to go forth not by the power of the sword but through the preaching of the Word.