Church, Place and Organization: the Development of the New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards an Understanding of Lived Methodism

Telling Our Stories: Towards an Understanding of Lived Methodism Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Edwards, Graham M. Citation Edwards, G. M. (2018). Telling Our Stories: Towards an Understanding of Lived Methodism. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, United Kingdom. Publisher University of Chester Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 28/09/2021 05:58:45 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/621795 Telling Our Stories: Towards an Understanding of Lived Methodism Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Chester for the degree of Doctor of Professional Studies in Practical Theology By Graham Michael Edwards May 2018 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work is my own, but I am indebted to the encouragement, wisdom and support of others, especially: The Methodist Church of Great Britain who contributed funding towards my research. The members of my group interviews for generously giving their time and energy to engage in conversation about the life of their churches. My supervisors, Professor Elaine Graham and Dr Dawn Llewellyn, for their endless patience, advice and support. The community of the Dprof programme, who challenged, critiqued, and questioned me along the way. Most of all, my family and friends, Sue, Helen, Simon, and Richard who listened to me over the years, read my work, and encouraged me to complete it. Thank you. 2 CONTENTS Abstract 5 Summary of Portfolio 6 Chapter One. Introduction: Methodism, a New Narrative? 7 1.1 Experiencing Methodism 7 1.2 Narrative and Identity 10 1.3 A Local Focus 16 1.4 Overview of Thesis 17 Chapter Two. -

Denominations Andministries

THE ESSENTIAL HANDBOOK OF DENOMINATIONS AND MINISTRIES GEORGE THOMAS KURIAN AND SARAH CLAUDINE DAY, EDITORS C George Thomas Kurian and Sarah Claudine Day, eds., The Essential Handbook of Denominations and Ministries Baker Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2017. Used by permission. _Kurian-Day_BakerHandbook_JK_bb.indd 3 11/18/16 11:16 AM These websites are hyperlinked. www.bakerpublishinggroup.com www.bakeracademic.com © 2017 by George Thomas Kurian www.brazospress.com Published by Baker Books www.chosenbooks.com a division of Baker Publishing Group P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287 www.revellbooks.com http://www.bakerbooks.com www.bethanyhouse.com Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kurian, George Thomas, editor. Title: The essential handbook of denominations and ministries / George Thomas Kurian and Sarah Claudine Day, editors. Description: Grand Rapids : Baker Books, 2017. Identifiers: LCCN 2016012033 | ISBN 9780801013249 (cloth) Subjects: LCSH: Christian sects. Classification: LCC BR157 .E87 2017 | DDC 280.0973—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016012033 Scripture quotations labeled ASV are from the American Standard Version of the Bible. Scripture quotations labeled KJV are from the King James Version of the Bible. Scripture quotations labeled NASB are from the New American Standard Bible®, copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. -

February 12, 2021 RUSSELL EARLE RICHEY

February 12, 2021 RUSSELL EARLE RICHEY Durham Address: 1552 Hermitage Court, Durham, NC 27707; PO Box 51382, 27717-1382 Telephone Numbers: 919-493-0724 (Durham); 828-245-2485 (Sunshine); Cell: 404-213-1182 Office Address: Duke Divinity School, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0968, 919-660-3565 Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Birthdate: October 19, 1941 (Asheville, NC) Parents: McMurry S. Richey, Erika M. Richey, both deceased Married to Merle Bradley Umstead (Richey), August 28, 1965. Children--William McMurry Richey, b. December 29, 1970 and Elizabeth Umstead Richey Thompson, b. March 3, 1977. William’s spouse--Jennifer (m. 8/29/98); Elizabeth’s spouse–Bennett (m. 6/23/07) Grandchildren—Benjamin Richey, b. May 14, 2005; Ruby Richey, b. August 14, 2008; Reeves Davis Thompson, b. March 14, 2009; McClain Grace Thompson, b June 29, 2011. Educational History (in chronological order); 1959-63 Wesleyan University (Conn.) B.A. (With High Honors and Distinction in History) 1963-66 Union Theological Seminary (N.Y.C.) B.D. = M.Div. 1966-69 Princeton University, M.A. 1968; Ph.D. 1970 Honors, Awards, Recognitions, Involvements and Service: Wesleyan: Graduated with High Honors, Distinction in History, B.A. Honors Thesis on African History, and Trench Prize in Religion; Phi Beta Kappa (Junior year record); Sophomore, Junior, and Senior Honor Societies; Honorary Woodrow Wilson; elected to post of Secretary-Treasurer for student body member Eclectic fraternity, inducted into Skull and Serpent, lettered in both basketball and lacrosse; selected to participate in Operation Crossroads Africa, summer 1981 Union Theological Seminary: International Fellows Program, Columbia (2 years); field work in East Harlem Protestant Parish; participated in the Student Interracial Ministry, summer 1964; served as national co-director of SIM, 1964-65. -

Download (11MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] "THE TRIBE OF DAN": The New Connexion of General Baptists 1770 -1891 A study in the transition from revival movement to established denomination. A Dissertation Presented to Glasgow University Faculty of Divinity In Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Frank W . Rinaldi 1996 ProQuest Number: 10392300 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10392300 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. -

How English Baptists Changed the Early Modern Toleration Debate

RADICALLY [IN]TOLERANT: HOW ENGLISH BAPTISTS CHANGED THE EARLY MODERN TOLERATION DEBATE Caleb Morell Dr. Amy Leonard Dr. Jo Ann Moran Cruz This research was undertaken under the auspices of Georgetown University and was submitted in partial fulfillment for Honors in History at Georgetown University. MAY 2016 I give permission to Lauinger Library to make this thesis available to the public. ABSTRACT The argument of this thesis is that the contrasting visions of church, state, and religious toleration among the Presbyterians, Independents, and Baptists in seventeenth-century England, can best be explained only in terms of their differences over Covenant Theology. That is, their disagreements on the ecclesiological and political levels were rooted in more fundamental disagreements over the nature of and relationship between the biblical covenants. The Baptists developed a Covenant Theology that diverged from the dominant Reformed model of the time in order to justify their practice of believer’s baptism. This precluded the possibility of a national church by making baptism, upon profession of faith, the chief pre- requisite for inclusion in the covenant community of the church. Church membership would be conferred not upon birth but re-birth, thereby severing the links between infant baptism, church membership, and the nation. Furthermore, Baptist Covenant Theology undermined the dominating arguments for state-sponsored religious persecution, which relied upon Old Testament precedents and the laws given to kings of Israel. These practices, the Baptists argued, solely applied to Israel in the Old Testament in a unique way that was not applicable to any other nation. Rather in the New Testament age, Christ has willed for his kingdom to go forth not by the power of the sword but through the preaching of the Word. -

Proceedings Wesley Historical Society

Proceedings OF THE Wesley Historical Society Editor: REv. WESLEY F. SWIFT Volume XXVIII September 1952 EDITORIAL VERY member of the Wesley Historical Society will wish to congratulate our Secretary, the Rev. Frank Baker, who has Ebeen awarded the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by the University of Nottingham for a thesis entitled: "The Rev. William Grimshaw (1708-1763) and the eighteenth-century revival of religion in England ". Dr. Baker's friends never cease to marvel at his capacity for meticulous and sustained research, his mastery of detail, and the wide range of his interests, though they often wish that in his eagerness to crowd his days he would not so fre quently burn the candle at both ends. He is a tower of strength to our Society., and his learning as well as the contents of his numerous filing cabinets are always at the disposal of any inquiring student. We have been privileged to read in typescript the thesis on Grim shaw of Haworth. It is a massive work on an important subject, and will never be superseded for the simple reason that every possible scrap of information, direct and indirect, has been care fully gathered and woven into the theme. We are glad to know that the work is being prepared for publication, and meanwhile we rejoice in Dr. Frank Baker's new distinction and the reflected glory which has thereby come to our Society . • • • • We did not know that there existed a Swedish Methodist His torical Society until a letter recently arrived from its Secretary, the Rev. Vilh. -

Paul J Worsnop June 2000 Chester-Ie-Street, Co Durham

Durham E-Theses Facilitating mission in British Methodist churches: lessons from historical and contemporary models Worsnop, Paul J How to cite: Worsnop, Paul J (2000) Facilitating mission in British Methodist churches: lessons from historical and contemporary models, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4206/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 FACILITATING MISSION IN BRITISH METHODIST CHURCHES LESSONS FROM HISTORICAL AND CONTEMPORARY MODELS The COI)yright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should he IlUhlished in any form, including Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent. All information derh'ed from this thesis must he acknowledged aJ)l,ropriately. Paul J Worsnop June 2000 Submitted to the University of Durham for degree of Master of Arts (Theology Department) \"I '; ,"'- ~-I- ~ 7 JAN lUUl FACILITATING MISSION IN BRITISH METHODIST CHURCHES LESSONS FROM HISTORICAL AND CONTEMPORARY MODELS Paul J Worsllop - MA Degree (Durham) - JUlie 2000 ABSTRACT The recent rapid decline and current ageing membership of British Methodism has given rise to questions as to whether it has a viable future. -

INTEGRITY a Lournøl of Christiøn Thought

INTEGRITY A lournøl of Christiøn Thought PLIBLISHED BY THE COMMISSION FOR THEOLOGICALINTEGRITY OF THE NATIONALASSOCIATION OF FREE WILL BAPTISTS Editor J. Matthew Pinson Pastor, Colquitt Free Will Baptist Church, Colquitt, Georgia Assistant Editor Paul V. Harrison Pastot Cross Timbers Free Will Baptist Church, Nashville, Tennessee Editoriøl Boørd Timothy Eaton, Vice-President, Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College Daryl W. Ellis, Pastor, Butterfield Free Will Baptist Church, Aurora, Illinois F. Leroy Forlines, Professor, Free Will Baptist Bible College Keith Fletcher, Editor-in-Chief Randall House Publications Jeff Manning, Pastor, Unity Free Will Baptist Church, Greenville, North Carolina Garnett Reid, Professor, Free Will Baptist Bible College Integrity: A fournal of Christiøn Thought is published in cooperation with Randall House Publications, Free Will Baptist Bible College, and Hillsdale Free Will Baptist College. It is partially funded by those institutions as well as a number of interested churches and indi- viduals. Integrity exists to stimulate and provide a forum fo¡ Cfuistian scholarship among Free Will Baptists and to fulfill the purposes of the Commission for Theological Integrity. The Commission for Theological Integrity consists of the following members: F. Leroy Forlines (chairman), Daryl W Ellis, Paul V. Harrisor¡ Jeff Manning, and f. Matthew Pinson. Manuscripts for publication and communications on editorial matters should be di¡ected to the attention of the editor at the following address: 114 Bremond Street, Colquitt, Georgia 37737.B-mail inquiries should be addressed to: [email protected]. Additional copies of the journal can be requested for $6.00 (cost includes shipping). Typeset by Henrietta Brown Printed by Rnndall House Publícations, Nøshz¡ille, Tennessee 37217 @ Copyright 2000 by the Commission for Theological lntegrity, National Association of Free Will Baptists Printed in the United States of America Contents Preface . -

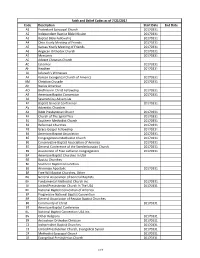

Code Description Start Date End Date A1 Protestant Episcopal Church

Faith and Belief Codes as of 7/21/2017 Code Description Start Date End Date A1 Protestant Episcopal Church 20170331 A2 Independent Baptist Bible Mission 20170331 A3 Baptist Bible Fellowship 20170331 A4 Ohio Yearly Meeting of Friends 20170331 A5 Kansas Yearly Meeting of Friends 20170331 A6 Anglican Orthodox Church 20170331 A7 Messianic 20170331 AC Advent Christian Church AD Eckankar 20170331 AH Heathen 20170331 AJ Jehovah’s Witnesses AK Korean Evangelical Church of America 20170331 AM Christian Crusade 20170331 AN Native American AO Brethren In Christ Fellowship 20170331 AR American Baptist Convention 20170331 AS Seventh Day Adventists AT Baptist General Conference 20170331 AV Adventist Churches AX Bible Presbyterian Church 20170331 AY Church of The Spiral Tree 20170331 B1 Southern Methodist Church 20170331 B2 Reformed Churches 20170331 B3 Grace Gospel Fellowship 20170331 B4 American Baptist Association 20170331 B5 Congregational Methodist Church 20170331 B6 Conservative Baptist Association of America 20170331 B7 General Conference of the Swedenborgian Church 20170331 B9 Association of Free Lutheran Congregations 20170331 BA American Baptist Churches In USA BB Baptist Churches BC Southern Baptist Convention BE Armenian Apostolic 20170331 BF Free Will Baptist Churches, Other BG General Association of General Baptists BH Fundamental Methodist Church Inc. 20170331 BI United Presbyterian Church In The USA 20170331 BN National Baptist Convention of America BP Progressive National Baptist Convention BR General Association of Regular Baptist -

The Rise of the Baptists in South Carolina: Origins, Revival, and Their Enduring Legacy

Bound Away: The Liberty Journal of History Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 6 November 2018 The Rise of the Baptists in South Carolina: Origins, Revival, and their Enduring Legacy Steven C. Pruitt Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ljh Part of the History of Religion Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pruitt, Steven C. (2018) "The Rise of the Baptists in South Carolina: Origins, Revival, and their Enduring Legacy," Bound Away: The Liberty Journal of History: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ljh/vol2/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bound Away: The Liberty Journal of History by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rise of the Baptists in South Carolina: Origins, Revival, and their Enduring Legacy Abstract Baptists have played an important role in the development of the religious landscape in the United States since the First Great Awakening. This religious sect’s core of influence eventually migrated south around the turn of the nineteenth century. A battle over the soul of the South would be waged by the Baptists, along with the Methodists, and Presbyterians also moving into the area. This Protestant surge coincided with the decrease in influence of the Episcopal (Anglican) Church after ties with England were severed. In many ways, this battle for the future would occur in the newly settled backcountry of South Carolina. -

Lowship International * Independent Baptist Fellowship of North America

Alliance of Baptists * American Baptist Association * American Baptist Churches USA * Association of Baptist Churches in Ireland * Association of Grace Baptist Churches * Association of Reformed Baptist Churches of America * Association of Regular Baptist Churches * Baptist Bible Fellowship International * Baptist Conference of the Philippines * Baptist Convention of Ontario and Quebec * Baptist Convention of Western Cuba * Baptist General Conference (formally Swedish Baptist General Conference) * Baptist General Conference of Canada * Baptist General Convention of Texas * Baptist Missionary Association of America * Baptist Union of Australia * Baptist Union of Great Britain * Baptist Union of New Zealand * Baptist Union of Scotland * Baptist Union of Western Can- ada * Baptist World Alliance * Bible Baptist * Canadian Baptist Ministries * Canadian Convention of Southern Baptists * Cen- tral Baptist Association * Central Canada Baptist Conference * Christian Unity Baptist Association * COLORED PRIMITIVE BAPTISTS * Conservative Baptist Association * Conservative Baptist Association of America * Conservative Baptists * Continental Baptist Churches * Convención Nacional Bautista de Mexico * Convention of Atlantic Baptist Churches * Coop- erative Baptist Fellowship * Crosspoint Chinese Church of Silicon Valley * European Baptist Convention * European Bap- tist Federation * Evangelical Baptist Mission of South Haiti * Evangelical Free Baptist Church * Fellowship of Evan- gelical Baptist Churches in Canada * Free Will Baptist Church * Fun- damental -

1 British Baptist Crucicentrism Since the Late Eighteenth Century David

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository 1 British Baptist Crucicentrism since the Late Eighteenth Century David Bebbington Professor of History, University of Stirling On 24 May 1791 William Carey, soon to become the pioneer of the Baptist Missionary Society, was ordained to the Christian ministry at his meeting house in Harvey Lane, Leicester. His friend Samuel Pearce, minister in Birmingham, preached the evening ordination sermon. Pearce’s text was Galatians 6:14, ‘God forbid that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by whom the world is crucified unto me, and I unto the world.’ His message was that, as a minister, Carey should concentrate on proclaiming Christ crucified.1 This gathering of Baptists who were about to launch the worldwide mission of the Anglo-American Evangelical churches strongly believed that the cross was the fulcrum of the Christian faith. Andrew Fuller, who had delivered the charge to the people on the day of Carey’s ordination, was of the same mind. In a sermon on a different occasion Fuller insisted that the death of Christ was not so much a portion of the body of Christian doctrine as its life- blood. ‘The doctrine of the cross’, he declared, ‘is the christian doctrine.’2 A similar refrain was sustained by Baptists during the nineteenth century. ‘Of all the doctrines of the gospel’, wrote the contributor of an article on the atonement to the Baptist Magazine in 1819, ‘there is none more important than this’.3 A similar point was made in a more florid way in the same journal eighteen years later.