Oligopoly Coordination, Economic Analysis, and the Prophylactic Role of Horizontal Merger Enforcement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly Monopolistic Competition (獨占性競爭) an Introduction to Oligopoly (寡占) Models of Oligopoly

Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly Monopolistic Competition (獨占性競爭) An introduction to Oligopoly (寡占) Models of Oligopoly © 2003 South-Western/Thomson Learning 1 Characteristics of Monopolistic Competition Many producers offer products: close substitutes but not identical Supplier has power over price Price makers Low barriers to enter In the long run can enter/leave Sellers act independently of each other 2 1 Product Differentiation In perfect competition, product is homogenous In Monopolistic competition, Sellers differentiate products in four basic ways Physical differences and qualities • Shampoo: size, color, focus normal (dry) hair … Location • The number of variety of locations – Shopping mall: cheap, variety of goods – Convenience stores: convenience Accompanying services • Ex: Product demonstration, money back/no return Product image • Ex: High quality, natural ingredients … 3 Short-Run Profit Maximization or Loss Minimization Because products are different Each firm has some control over price demand curve slopes downward Many firms sell close substitutes, Raises price Æ lose customers Demand is more elastic than monopolist’s but less elastic than a perfect competitors 4 2 Price Elasticity of Demand The elasticity demand depends on The number of rival firms that produce similar products The firm’s ability to differentiate its product more elastic: if more competing firms Less elastic: differentiated product 5 Profit Maximization as MR=MC The downward-sloping demand curve MR curve • slopes downward and • below the demand curve Cost curves are similar to those developed before Next slide depicts the relevant curves for the monopolistic competitor 6 3 Profit Maximization In the short run, if revenue >variable cost Profits are max. as MR=MC. -

Price Bargaining and Competition in Online Platforms: an Empirical Analysis of the Daily Deal Market

Price Bargaining and Competition in Online Platforms: An Empirical Analysis of the Daily Deal Market Lingling Zhang Doug J. Chung Working Paper 16-107 Price Bargaining and Channel Selection in Online Platforms: An Empirical Analysis of the Daily Deal Market Lingling Zhang University of Maryland Doug J. Chung Harvard Business School Working Paper 16-107 Copyright © 2016, 2018, 2019 by Lingling Zhang and Doug J. Chung Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Funding for this research was provided by Harvard Business School and the institution(s) of any co-author(s) listed above. Price Bargaining and Competition in Online Platforms: An Empirical Analysis of the Daily Deal Market Lingling Zhang Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, United States, [email protected] Doug J. Chung Harvard Business School, Harvard University, Boston, MA 02163, United States, [email protected] Abstract The prevalence of online platforms opens new doors to traditional businesses for customer reach and revenue growth. This research investigates platform competition in a setting where prices are determined by negotiations between platforms and businesses. We compile a unique and comprehensive data set from the U.S. daily deal market, where merchants offer deals to generate revenues and attract new customers. We specify and estimate a two-stage supply-side model in which platforms and merchants bargain on the wholesale price of deals. -

PRICE THEORY Price Theory Is a Microeconomics Principle That

PRICE THEORY Price theory is a microeconomics principle that involves the analysis of demand and supply in determining an appropriate price point for a good or service. This section is concerned with the study of prices and it forms the basis of economic theory. PRICE DEFINITION Price is the exchange value of a commodity expressed in monetary terms. OR Price is the monetary value of a good or service. For example the price of a mobile phone may be shs. 84,000/=. PRICE DETERMINATION Prices can be determined in different ways and these include; 1. Bargaining/ haggling. This involves the buyer negotiating with the seller until they reach an agreeable price. The seller starts with a higher price and the buyer starts with a lower price. During bargaining, the seller keeps on reducing the price and the buyer keeps on increasing until they agree on the same price. 2. Auctioning/ bidding This involves prospective buyers competing to buy a commodity through offering bids. The commodity is usually taken by the highest bidder. This method is common in fundraising especially in churches, disposal of public and company assets and sell of articles that sellers deem are treasured by the public. Note that the price arising out of an auction does not reflect the true value of the commodity. 3. Market forces of demand and supply. In this case, the price is determined at the point of intersection of the market forces of demand and supply. This is common in a free enterprise economy. The price set is called the equilibrium price. -

Applied Microeconomics: Consumption, Production and Markets David L

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Agricultural Economics Textbook Gallery Agricultural Economics 6-2012 Applied Microeconomics: Consumption, Production and Markets David L. Debertin University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/agecon_textbooks Part of the Agricultural Economics Commons Recommended Citation Debertin, David L., "Applied Microeconomics: Consumption, Production and Markets" (2012). Agricultural Economics Textbook Gallery. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/agecon_textbooks/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Agricultural Economics at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Agricultural Economics Textbook Gallery by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. __________________________ Applied Microeconomics Consumption, Production and Markets David L. Debertin ___________________________________ Applied Microeconomics Consumption, Production and Markets This is a microeconomic theory book designed for upper-division undergraduate students in economics and agricultural economics. This is a free pdf download of the entire book. As the author, I own the copyright. Amazon markets bound print copies of the book at amazon.com at a nominal price for classroom use. The book can also be ordered through college bookstores using the following ISBN numbers: ISBN‐13: 978‐1475244342 ISBN-10: 1475244347 Basic introductory college courses in microeconomics and differential calculus are the assumed prerequisites. The last, tenth, chapter of the book reviews some mathematical principles basic to the other chapters. All of the chapters contain many numerical examples and graphs developed from the numerical examples. -

Introductory Price Elasticity

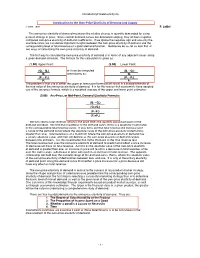

IntroductoryPriceElasticity.xls Introduction to the Own-Price Elasticity of Demand and Supply © 2003, 1999 P. LeBel The own-price elasticity of demand measures the relative change in quantity demanded for a one percent change in price. Since normal demand curves are downward-sloping, they all have negative computed own-price elasticity of demand coefficients. If we ignore the negative sign and use only the absolute value, we can derive important insights between the own-price elasticity of demand and the corresponding level of total revenue of a given demand function. Before we do so, let us look first at two ways of calculating the own-price elasticity of demand. The first way to calculate the own-price elasticity of demand is in terms of any adjacent values along a given demand schedule. The formula for this calculation is given as: (1.00) Upper Point: (2.00) Lower Point: (Q1 - Q2) or it can be computed (Q1 - Q2) Q1 alternatively as: Q2 (P1 - P2) (P1 - P2) P1 P2 The problem is that use of either the upper or lower point formulat will result in a biased estimate of the true value of the own-price elasticity of demand. It is for this reason that economists have adopted use of the arc-price formula, which is a weighted average of the upper and lower point estimates: (3.00) Arc-Price, or Mid-Point, Demand Elasticity Formula: (Q1 - Q2) (Q1+Q2) (P1-P2) (P1+P2) We turn next to total revenue, which is the price times the quantity along each point of the demand schedule. -

Competition-Based Dynamic Pricing in Online Retailing: a Methodology Validated with Field Experiments

Competition-Based Dynamic Pricing in Online Retailing: A Methodology Validated with Field Experiments Marshall Fisher The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, fi[email protected] Santiago Gallino Tuck School of Business, Dartmouth College, [email protected] Jun Li Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, [email protected] A retailer following a competition-based dynamic pricing strategy tracks competitors' price changes and then must answer the following questions: (1) Should the retailer respond? (2) If so, respond to whom? (3) How much of a response? (4) And on which products? The answers require unbiased measures of price elasticity as well as accurate knowledge of competitor significance and the extent to which consumers compare prices across retailers. To quantify these factors empirically, there are two key challenges: first, the endogeneity associated with almost any type of observational data, where prices are correlated with demand shocks observable to pricing managers but not to researchers; and second, the absence of competitor sales infor- mation, which prevents efficient estimation of a full consumer-choice model. We address the first issue by conducting a field experiment with randomized prices. We resolve the second issue by proposing a novel iden- tification strategy that exploits the retailer's own and competitors stock-outs as a valid source of variation to the consumer choice set. We estimate an empirical model capturing consumer choices among substitutable products from multiple retailers. Based on the estimates, we propose a best-response pricing strategy that takes into account consumer choice behavior, competitors' actions, and supply parameters (procurement costs, margin target, and manufacturer price restrictions). -

Microeconomics

MICROECONOMICS This book is a compilation from MBA 1304-Microeconomics Course. The copyright of the book belongs to Bangladesh Open University. The compiler is not liable for any copyright issue with this book. Compiled by: Md. Mahfuzur Rahman Assistant Professor (Economics) School of Business Bangladesh Open University School of Business BANGLADESH OPEN UNIVERSITY MICROECONOMICS 1 Contents Unit 1: Introduction Lesson 1: Nature and Methodology of Economics Lesson 2: The Basic Problems of an Economy Unit 2: Demand and Supply Lesson 1: Theory of Demand Lesson 2: Theory of Supply Lesson 3: Price Determination: Equilibrium of Demand and Supply Unit 3: Elasticity of Demand Lesson 1: Elasticity of Demand Unit-4: Consumer Behavior Lesson 1: Introduction Lesson 2: The Cardinal Utility Approach Lesson 3: Ordinal Utility Theory Indifference curves Unit-5: Production, Cost and Supply Lesson 1: Concepts Related to Production Lesson 2: Short-run and Long-run Cost Curves Lesson 3: Laws of Returns Unit 6: Perfect Competition Lesson 1: Characteristics of Perfect Competition, AR & MR Curves in Perfect Competition Lesson 2: Equilibrium of a Competitive Firm Unit 7: Monopoly Lesson 1: Nature of Monopoly Market and AR and MR Curves in Monopoly Market Lesson 2: Price and Output Determination under Monopoly: Equilibrium of Monopolist Lesson 3: Monopoly Power, Regulating the Monopoly and the Comparison between Competitive and Monopoly Markets Unit 8 Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly Lesson 1: Monopolistic Competition Lesson 2: Oligopoly 2 Unit 1: INTRODUCTION -

1 Price Segmentation in the Wine Industry: the Effects of Market Entry

Price Segmentation in the Wine Industry: The Effects of Market Entry Steven S. Cuellar* Department of Economics Sonoma State University Rohnert Park, CA 94928 [email protected] Robert Eyler Department of Economics Sonoma State University Rohnert Park, CA 94928 [email protected] Draft: Do not quote, reference, or use otherwise *Denotes contact author, Copyright © 2004 1 Abstract This study suggests that microeconomic theory provides some insight as to the future price structure of the wine industry. Following examples from the pharmaceutical industry, theoretical evidence shows that due to market entry, the price point structure in the wine industry may break down and result in only two price points. The conditions for such a bifurcation of the wine market seem to be in place due to the entry of value wines, at prices under $4 per 750ml container. We also provide brief empirical evidence the new structure has begun to form, but suggest that more research is needed. The wine industry, which has invested in millions per year in advertising and product differentiation to enter different price segments, may be reduced to low and high priced wine only. 2 Price Segmentation in the Wine Industry: The Effects of Market Entry 1. INTRODUCTION The wine industry’s pricing structure has traditionally been categorized into five segments or price points. These price points constitute market segments. Although these market segments have existed for some time, recent events may be acting to permanently change pricing structure. The success of the proprietary brand Charles Shaw, sold for around two dollars per bottle, perhaps best epitomizes this phenomena.1 Standard economic theory tells us that competitive entry such as this results in an overall reduction in prices. -

Analysis of Postal Price Elasticities

May 1, 2013 The following white paper contains an examination of the price sensitivity of postal customers of three market dominant Postal Service products: First-Class Mail, Standard Mail, and Periodicals. The marketplace for traditional Postal Service products is increasingly competitive. In addition to the long term trend toward electronic media, Postal Service products face intense pressures brought about by the Great Recession. This paper explores an open question raised by these disruptive trends: Are Postal Service customers becoming more price sensitive? Though intuition may suggest that growing competition would have this effect, the answer to this question is best found by letting the data do the talking. Toward that end, this paper presents the results of an open-minded, rigorous empirical review of the demand for these postal products. Price sensitivity was analyzed with a battery of tests using both the Postal Service demand models and alternative models. The analysis was subjected to extensive peer review. We were surprised to find that, no matter how we stressed the models or which models we used, the data told the same story: Demand for postal products is not becoming more price sensitive. In fact, a case can be made that these products are becoming less price sensitive. This may be because customers most likely to leave the Postal Service for the Internet have already done so, leaving the remaining customers more loyal in the face of price increases. In the course of our analysis, we did uncover some technical problems with the Postal Service’s demand models. We recommend that the Postal Service make adjustments to its models as appropriate. -

Pricing of Interrelated Goods in Oligopoly

IISSEETT WORKING PAPER SERIES WP 014‐08 OCTOBER 2008 Pricing Interrelated Goods in Oligopoly Sandro Shelegia The International School of Economics at Tbilisi State University (ISET) is supported by BP, the Government of Georgia, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Higher Education Support Program of the Open Society Institute, the Swedish International Development Agency and the World Bank. International School of Economics at Tbilisi State University 16 Zandukeli Street, Tbilisi 0108, Georgia www.iset.ge e‐mail: [email protected] Pricing Interrelated Goods In Oligopoly Sandro Shelegia∗ Department of Economics and Business Universitat Pompeu Fabra This Draft: July 31, 2008 Abstract In this paper we propose a two-good model of price competition in an oligopoly where the two goods can be complements or substitutes and each retailer has a captive consumer base `ala Burdett and Judd(1983). We find that the symmetric Nash Equilibrium of this model features atomless pricing strategies for both goods. When the two goods are complements the prices charged by any retailer are, at least locally, negatively correlated so if one of the goods is priced high the other one is on a discount. This finding is supported by an empirical observation that simultaneous discounts of complements are infrequent. In contrast, if the goods are substitutes or independently valued the prices will be randomized independently unless the less valuable substitute is not sold at all. In the case of complements the retailers earn higher profit relative to the case of selling both goods only as a bundle. The ability to \discriminate" between the captives and the shoppers through keeping the sum of the two prices high while setting one of the prices low drives the result. -

The Hidden Costs of Free Goods: Implications for Antitrust Enforcement

Berkeley Law From the SelectedWorks of Daniel L. Rubinfeld 2016 The iddeH n Costs of Free Goods: Implications for Antitrust Enforcement Daniel L Rubinfeld, Berkeley Law Michal Gal, University of Haifa Available at: https://works.bepress.com/daniel_rubinfeld/52/ +(,121/,1( Citation: 80 Antitrust L.J. 521 2015-2016 Provided by: BerkeleyLaw Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Sun Aug 14 03:17:12 2016 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0003-6056 THE HIDDEN COSTS OF FREE GOODS: IMPLICATIONS FOR ANTITRUST ENFORCEMENT MICHAL S. GAL DANIEL L. RUBINFELD* Many valuable goods and services introduced in recent years are provided in the marketplace free of charge.1 Some examples include Linux's operating system, Google's search engine, Facebook's or Twitter's social network, Wikipedia's online encyclopedia, YouTube's online video and music stream- ing services, Dropbox's online storage services, and Typepad's blogging plat- forms. Although the phenomenon of free consumer goods is not new, free goods and services (free goods) have gained particular prominence with the 2 rise of the Internet. * Michal Gal is Professor and Director of the Forum for Law and Markets, University of Haifa Faculty of Law. -

Dynamic Oligopoly Pricing with Asymmetric Information: Implications for Mergers

Dynamic Oligopoly Pricing with Asymmetric Information: Implications for Mergers Andrew Sweeting Xuezhen Tao University of Maryland and NBER∗ Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Xinlu Yao University of Maryland April 2018 Abstract Existing theoretical and structural analyses of mergers in differentiated product markets assume that firms have complete information about both their own and their rivals' demand and marginal costs. While the complete information assumption simplifies the analysis, we show that equilibrium price levels may change significantly when there are small amounts of asymmetric information about serially-correlated marginal costs, as firms may have incentives to raise their prices in order to signal their costs, and therefore the likely level of their future prices, to competitors. We show that signaling effects could lead merger simulations that assume complete information to underpredict post-merger price rises quite significantly, and that they are also capable of explaining the magnitude of price increases often observed after actual mergers. JEL CODES: D43, D82, L13, L41, L93. Keywords: signaling, strategic investment, asymmetric information, oligopoly pricing, dynamic pricing. ∗Contact: [email protected]. We thank Dan Vincent, Nate Miller and several seminar participants for useful comments. Carl Mela and Mike Krueger helped to provide access to the IRI academic data, and we benefited greatly from John Singleton's work with the beer data on another project. All errors are our own. 1 Introduction Both theoretical and empirical analyses of mergers, as well as many other phenomena in Industrial Organization, typically assume complete information, i.e., that all firms know both their own and their rivals' demands and marginal costs exactly.