268. Pigs in Cameroon.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Fako : Village Dictionary of Fako Division

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIOUE ET TECHNIOUE OUTRE· MER Il REPUBLIQUE UNIE DU CAMEROUN DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION SECTION DE GEOGRAPHIE 1 OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIm~TIFIQUE REPUBLIQUE UNIE ET TECmUQUE OUTRE-lViER DU CAlvŒROUN UNITED REPUBLIC OF CANEROON CENTRE O.R.S.T.O.N DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION Juillet 1973 July 1973 COPYRIGHT O.R.S.T.O.M 1973 TABLE DES NATIERES CONTENTS i l j l ! :i i ~ Présentation •••••.•.•.....••....•.....•....••••••.••.••••••.. 1 j Introduction ........................................•• 3 '! ) Signification des principaux termes utilisés •.............• 5 î l\lIeaning of the main words used Tableau de la population du département •...••.....•..•.•••• 8 Population of Fako division Département du Fako : éléments de démographie •.•.... ..••.•• 9 Fako division: demographic materials Arrondissements de Muyuka et de Tiko : éléments de . démographie 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 11uyul{a and Tileo sl)..bdivisions:demographic materials Arrondissement de Victoria: éléments de démographie •••.••• 11 Victoria subdivision:demographic materials Les plantations (12/1972) •••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••• 12 Plantations (12/1972) Liste des villages par arrondissement, commune et graupement 14 List of villages by subdivision, area council and customary court Signification du code chiffré •..•••...•.•...•.......•.•••.• 18 Neaning of the code number Liste alphabétique des villages ••••••.••••••••.•.•..•••.•.• 19 -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

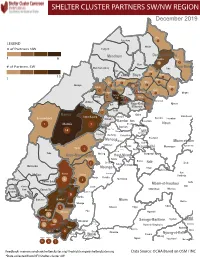

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

MINMAP South-West Region

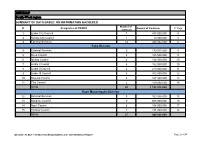

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Limbe City Council 7 475 000 000 4 2 Kumba City Council 1 10 000 000 5 3 External Services 14 440 032 000 6 Fako Division 4 External Services 9 179 015 000 8 5 Buea Council 5 125 500 000 9 6 Idenau Council 4 124 000 000 10 7 Limbe I Council 4 152 000 000 10 8 Limbe II Council 4 219 000 000 11 9 Limbe III Council 6 102 500 000 12 10 Muyuka Council 6 127 000 000 13 11 Tiko Council 5 159 000 000 14 TOTAL 43 1 188 015 000 Kupe Muanenguba Division 12 External Services 5 100 036 000 15 13 Bangem Council 9 605 000 000 15 14 Nguti Council 6 104 000 000 17 15 Tombel Council 7 131 000 000 18 TOTAL 27 940 036 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION Page 1 of 34 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Lebialem Division 16 External Services 5 134 567 000 19 17 Alou Council 9 144 000 000 19 18 Menji Council 3 181 000 000 20 19 Wabane Council 9 168 611 000 21 TOTAL 26 628 178 000 Manyu Division 18 External Services 5 98 141 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 6 119 500 000 22 20 Eyomojock Council 6 119 000 000 23 21 Mamfe Council 5 232 000 000 24 22 Tinto Council 6 108 000 000 25 TOTAL 28 676 641 000 Meme Division 22 External Services 5 85 600 000 26 23 Mbonge Council 7 149 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 1 27 000 000 27 25 Kumba I Council 3 65 000 000 27 26 Kumba II Council 5 83 000 000 28 27 Kumba III Council 3 84 000 000 28 TOTAL 24 493 600 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS -

MINMAP South-West Region

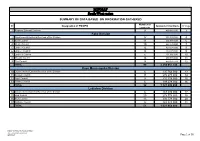

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 9 490 982 000 3 Fako Division 2 Départemental External Services of the Division 17 352 391 000 4 3 Buea Council 11 204 778 000 6 4 Idenau Council 10 224 778 000 7 5 Limbe I Council 12 303 778 000 8 6 Limbe II Council 13 299 279 000 9 7 Limbe III Council 6 151 900 000 10 8 Muyuka Council 16 250 778 000 11 9 Tiko Council 14 450 375 748 12 TOTAL 99 2 238 057 748 Kupe Muanenguba Division 10 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 135 764 000 13 11 Bangem Council 11 572 278 000 14 12 Nguti Council 9 215 278 000 15 13 Tombel Council 6 198 278 000 16 TOTAL 32 1 121 598 000 Lebialem Division 14 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 167 474 000 17 15 Alou Council 20 278 778 000 18 16 Menji Council 13 306 778 000 20 17 Wabane Council 12 268 928 000 21 TOTAL 51 1 021 958 000 PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION /MINMAP Page 1 of 36 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Manyu Division 18 Départemental External Services of the Division 9 240 324 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 10 260 278 000 23 20 Eyumojock Council 6 195 778 000 24 21 Mamfe Council 7 271 103 000 24 22 Tinto Council 7 219 778 000 25 TOTAL 39 1 187 261 000 Meme Division 23 Départemental External Services of the Division 4 82 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 5 171 533 000 26 25 Kumba -

South West Assessment

Cameroon Emergency Response – South West Assessment SOUTH WEST CAMEROON November 2018 – January 2019 - i - CONTENTS 1 CONTEXT ..................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 The crisis in numbers:.................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Overall Objectives of SW Assessment ........................................................................... 5 1.3 Area of Intervention ...................................................................................................... 6 2 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Assessment site selection: ............................................................................................ 8 2.2 Configuration of the assessment team: ........................................................................ 8 2.3 Indicators of vulnerability verified during the rapid assessment: ................................ 9 2.3.1 Nutrition and Health ............................................................................................. 9 2.3.2 WASH ..................................................................................................................... 9 3.1.1 Food Security ......................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Sources of Information ............................................................................................... -

Cholera Outbreak

Emergency appeal final report Cameroon: Cholera outbreak Emergency appeal n° MDRCM011 GLIDE n° EP-2011-000034-CMR 31 October 2012 Period covered by this Final Report: 04 April 2011 to 30 June 2012 Appeal target (current): CHF 1,361,331. Appeal coverage: 21%; <click here to go directly to the final financial report, or here to view the contact details> Appeal history: This Emergency Appeal was initially launched on 04 April 2011 for CHF 1,249,847 for 12 months to assist 87,500 beneficiaries. CHF 150,000 was initially allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the national society in responding by delivering assistance. Operations update No 1 was issued on 30 May 2011 to revise the objectives and budget of the operation. Operations update No 2 was issued on 31st May 2011 to provide financial statement against revised budget. Operations update No 3 was issued on 12 October 2011 to summarize the achievements 6 months into the operation. Operations update No 4 was issued on 29 February 2012 to extend the timeframe of the operation from 31st March to 30 June 2012 to cover the funding agreement with the American Embassy in Cameroon. PBR No M1111087 was submitted as final report of this operation to the American Embassy in Cameroon on 03 August 2012. Throughout the operation, Cameroon Red Cross volunteers sensitized the populations on PBR No M1111127 was submitted as final report of this how to avoid cholera. Photo/IFRC operation to the British Red Cross on 14 August 2012. Summary: A serious cholera epidemic affected Cameroon since 2010. -

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

SSA Infographic

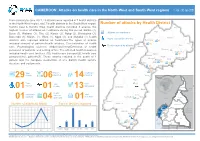

CAMEROON: Attacks on health care in the North-West and South-West regions 1 Jan - 30 Jun 2021 From January to June 2021, 29 attacks were reported in 7 health districts in the North-West region, and 7 health districts in the South West region. Number of attacks by Health District Kumbo East & Kumbo West health districts recorded 6 attacks, the Ako highest number of attacks on healthcare during this period. Batibo (4), Wum Buea (3), Wabane (3), Tiko (2), Konye (2), Ndop (2), Benakuma (2), Attacks on healthcare Bamenda (1), Mamfe (1), Wum (1), Nguti (1), and Muyuka (1) health Injury caused by attacks Nkambe districts also reported attacks on healthcare.The types of attacks Benakuma 01 included removal of patients/health workers, Criminalization of health 02 Nwa Death caused by attacks Ndu care, Psychological violence, Abduction/Arrest/Detention of health Akwaya personnel or patients, and setting of fire. The affected health resources Fundong Oku Kumbo West included health care facilities (10), health care transport(2), health care Bafut 06 Njikwa personnel(16), patients(7). These attacks resulted in the death of 1 Tubah Kumbo East Mbengwi patient and the complete destruction of one district health service Bamenda Ndop 01 Batibo Bali 02 structure and equipments. Mamfe 04 Santa 01 Eyumojock Wabane 03 Total Patient Healthcare 29 Attacks 06 impacted 14 impacted Fontem Nguti Total Total Total 01 Injured Deaths Kidnapping EXTRÊME-NORD Mundemba FAR-NORTH CHAD 01 01 13 Bangem Health Total Ambulance services Konye impacted Detention Kumba North Tombel NONORDRTH 01 04 destroyed 01 02 NIGERIA Bakassi Ekondo Titi Number of attacks by Month Type of facilities impacted AADAMAOUADAMAOUA NORTH- 14 13 NORD-OUESTWEST Kumba South CENTRAL 12 WOUESTEST AFRICAN Mbonge SOUTH- SUD-OUEST REPUBLIC 10 WEST Muyuka CCENTREENTRE 8 01 LLITITTORALTORAL EASESTT 6 5 4 4 Buea 4 03 Tiko 2 Limbe Atlantic SSUDOUTH 1 02 Ocean 2 EQ. -

CAMEROON Bulletin # 14

CAMEROON Bulletin # 14 CAMEROON North-West and South-West Regions, Health Cluster Update, 15-22 August 2020 23 August, 2020 COVID-19 SITUATION HIGHLIGHTS (as of 23 August 2020, 4:00 PM) CFR 4 % GLOBAL: 23,256,567+ 805,733+ Confirmed Cases To t a l Deaths 2% AFRICAN 1,178,630+ 27,596+ REGION: Confirmed Cases To t a l Deaths 2% CAMEROON: 18, 762+ 408 Confirmed Cases To t a l Deaths SOUTH - WEST REGION (as of 20 August 2020): 3% 717 5,089+ 1,120,000+ 24 COVID-19 testing in Tiko Health District using RDT on 16 August 2020 Confirmed Cases Total Tested To t a l Deaths* Total Passengers Screened NORTH - WEST REGION (as of 20 August 2020): 09% IMMEDIATE NEEDS: • Ensure the all health districts implement COVID-19 response activities 774 5,100+ 70 1,330,000+ (contact tracing, testing, sensitization and case management). Total Passengers Screened Confirmed Cases Total Tested To t a l Deaths • Stronger sensitization is required to counter the misinformation about the COVID-19 CASES PER SEX IN NWSW REGION: management of COVID-19 in the communities and at health facilities. 56% 44% Source: WHO; Ministry of Public Health- Male Female Cameroon, Johns Hopkins; nCoV • There is need for more CHWs to be trained and empowered to carry out KEY HIGHLIGHTS: community activities. • In NW region, 15 out of the I9 health districts reported confirmed cases • There is need to strengthen the information-sharing mechanism between of COVID-l9. 63 % of the cases have been recorded in Bamenda and 13% the health districts and regional delegation of public health. -

Press Release Organisation of Mobile Clinic

PRESS RELEASE ORGANISATION OF MOBILE CLINIC ACTIVITIES IN THE SOUTH WEST REGION Buea, February 16th, 2021 - The United Nations Populations Fund (UNFPA) and the Ministry of Public Health in partnership with the Cameroon Baptist Convention Hospital Services will on Thursday February 25th, 2021 set up a mobile clinic in the village of Kosala in the Kumba II Subdivision of Meme Division, South West Region of Cameroon at 7am. The event which falls under the World Bank Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility (PEF) Project run in the North West and South West Regions,aims at: • Reducing preventable maternal and new-born morbidities and mortalities in the North West Region (NWR) within the covid-19 pandemic and ongoing humanitarian crisis. • Reducing unmet need for Family planning in underserved populations and communities in the North West and South West Regions (NWSW) Insecurity, destruction of health infrastructure and ‘ghost towns’ have significantly reduced access to basic health services. During 2018, 175/368 (47%) and 184/368 (50%) facilities reported being affected by the crisis in the first and second half of the year respectively in the NW region (displacement of staff, destruction, difficulties in the supply of medical products, and difficulties in geographical access due to the destruction of roads or barricades/checkpoints). As of December 31, 2019, 9% (33/368) of health facilities in the NW were non-functional, with the health districts of Ako (50%), Batibo (21%), Nkambe (16%) and Bafut (16%) being the most affected, and 3% were partially -

Cameroon - South-West Region ! H Administrative Breakdowns NIGER

Cameroon - South-West Region ! h Administrative Breakdowns NIGER CHAD N N " NIGERIA " 0 0 ' !Mfom ' 0 0 3 3 ° ° 6 ! Iyahe 6 !Akumaye !Ngale !Wum CAMEROON CAR !Nkim EQUATORIAL GUINEA GABON CONGO NIGERIA NORTH-WEST AKWAYA !Bafut N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 !Acha Tugui 0 ° ° 6 6 !Ikom !Bamenda !Bali Baliben MANYU ! ! Mamfe Ayukaba ! Bachuo Akagbe ! WABANE EYUMODJOCK UPPER BAYANG LEBIALEM !Mbouda MAMFE ALOU N N " Bamougo!um " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 3 3 ° ° 5 5 ! Dschang FONTEM ! WEST ! Old Dunlop Town ! !Oban Company NGUTI ! KUPE-MANENGUBA TOKO !Kekem !Bafang !Melong SOUTH-WEST BANGEM !Passim N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 5 Calabar MUNDEMBA 5 ! !Nkongsamba !Ikot Offiong KONYE NDIAN TOMBEL !Manjo !Oron ! ISANGELE Tombel DIKOME BALUE ! Loum CAMEROON KUMBA ! KOMBO ITINDI EKONDO TITI 2ND Penja !Kumba ! KOMBO MEME !Ekondo Titi ABEDIMO KUMBA 3RD KUMBA 1ST N N " " 0 0 ' !Mbanga CENTRE ' 0 Longtoka 0 3 IDABATO ! 3 ° ° 4 BAMUSSO 4 !Ndokbélé !Mweli LITTORAL MBONGE MBONGE MUYUKA !Muyuka !Kaké !\ National capital FAKO !! Major Town WEST-COAST Bomono Gare ! BUEA ! Intermediate Town ! !Bonépoupa II ! Bomono Ba Buea ! Mbengué Small Town Mutengene ! TIKO ! International boundary Tiko Douala LIMBE !! LIMBE 2ND ! N N " 1ST Region boundary " 0 0 ' Limbe ' 0 0 ° ° 4 LIMBE 3RD 4 Department boundary Commune boundary ± River 0 10 20 E40QUATORIAL Surface Waterbody Kilometres !Edéa 8°30'0"E GUINEA 9°0'0"E 9°30'0"E 10°0'0"E Date Created: 20 Dec 2018 - Contact: [email protected] Data sources: Boundaries: OCHA, The designations employed and the presentation of material in the map(s) do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of WFP concerning Website: www.logcluster.org - Prepared by: HQ, OSE GIS ©OpenStreetMap Contributors © World Food Programme 2018 the legal or constitutional status of any country, territory, city or sea, or Map Reference: CMR_ADMIN_SudOuest_A3P_20181128 Populated places: GeoNames concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5