Pancakes Kisses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide Represents the Most Requested Songs at Weddings and Parties

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide represents the most requested songs at Weddings and Parties. Please circle songs you like and cross out the ones you don’t. You can also write-in additional requests on the back page! WEDDING SONGS ALL TIME PARTY FAVORITES CEREMONY MUSIC CELEBRATION THE TWIST HERE COMES THE BRIDE WE’RE HAVIN’ A PARTY SHOUT GOOD FEELIN’ HOLIDAY THE WEDDING MARCH IN THE MOOD YMCA FATHER OF THE BRIDE OLD TIME ROCK N ROLL BACK IN TIME INTRODUCTION MUSIC IT TAKES TWO STAYIN ALIVE ST. ELMOS FIRE, A NIGHT TO REMEMBER, RUNAROUND SUE MEN IN BLACK WHAT I LIKE ABOUT YOU RAPPERS DELIGHT GET READY FOR THIS, HERE COMES THE BRIDE BROWN EYED GIRL MAMBO #5 (DISCO VERSION), ROCKY THEME, LOVE & GETTIN’ JIGGY WITH IT LIVIN, LA VIDA LOCA MARRIAGE, JEFFERSONS THEME, BANG BANG EVERYBODY DANCE NOW WE LIKE TO PARTY OH WHAT A NIGHT HOT IN HERE BRIDE WITH FATHER DADDY’S LITTLE GIRL, I LOVED HER FIRST, DADDY’S HANDS, FATHER’S EYES, BUTTERFLY GROUP DANCES KISSES, HAVE I TOLD YOU LATELY, HERO, I’LL ALWAYS LOVE YOU, IF I COULD WRITE A SONG, CHICKEN DANCE ALLEY CAT CONGA LINE ELECTRIC SLIDE MORE, ONE IN A MILLION, THROUGH THE HANDS UP HOKEY POKEY YEARS, TIME IN A BOTTLE, UNFORGETTABLE, NEW YORK NEW YORK WALTZ WIND BENEATH MY WINGS, YOU LIGHT UP MY TANGO YMCA LIFE, YOU’RE THE INSPIRATION LINDY MAMBO #5BAD GROOM WITH MOTHER CUPID SHUFFLE STROLL YOU RAISE ME UP, TIMES OF MY LIFE, SPECIAL DOLLAR WINE DANCE MACERENA ANGEL, HOLDING BACK THE YEARS, YOU AND CHA CHA SLIDE COTTON EYED JOE ME AGAINST THE WORLD, CLOSE TO YOU, MR. -

The Ride in the Saddle

Copyright Page This book was automatically created by FLAG on April 19th, 2012, based on content retrieved from http://www.fanfiction.net/s/5838394/. The content in this book is copyrighted by Aylah50 or their authorised agent(s). All rights are reserved except where explicitly stated otherwise. This story was first published on March 23rd, 2010, and was last updated on March 25th, 2011. Any and all feedback is greatly appreciated - please email any bugs, problems, feature requests etc. to [email protected]. Table of Contents Summary 1. Chapter 1: Lightning Crashes 2. Chapter 2: I Wanna Be Sedated 3. Chapter 3: Alive 4. Chapter 4: Take On Me 5. Chapter 5: Sweet Child of Mine 6. Chapter 6: Everything You Want 7. Chapter 7: Wicked Garden 8. Chapter 8: Selling the Drama 9. Chapter 9: Now That We've Found Love 10. Chapter 10: Breaking the Habit 11. Chapter 11: The World I Know 12. Chapter 12: Holiday 13. Chapter 13: Pour Some Sugar On Me 14. Chapter 14: Everybody Hurts 15. Chapter 15: This I Promise You 16. Chapter 16: What a Girl Wants 17. Chapter 17: The Reason 18. Chapter 18: Possession 19. Chapter 19: Ghost of Me 20. Chapter 20: Call Your Name 21. Chapter 21: Home 22. Chapter 22 I Still Haven't Found 23. Chapter 23: Broken 24. Chapter 24: In the Air Tonight 25. Chapter 25: It's Not My Time 26. Chapter 26: I Alone 27. Chapter 27: Don't Wanna Miss a Thing 28. Chapter 28: Life is a Highway - 3 - 29. -

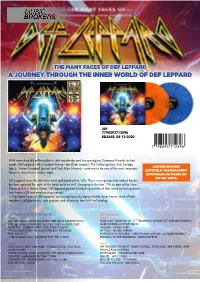

A Journey Through the Inner World of Def Leppard

THE MANY FACES OF DEF LEPPARD A JOURNEY THROUGH THE INNER WORLD OF DEF LEPPARD 2LP 7798093712896 RELEASE: 04-12-2020 With more than 65 million albums sold worldwide and two prestigious Diamond Awards to their credit, Def Leppard with its current line-up –Joe Elliott (vocals), Phil Collen (guitar), Rick Savage LIMITED EDITION (bass), Vivian Campbell (guitar) and Rick Allen (drums)— continue to be one of the most important GATEFOLD TRANSPARENT forces in rock music.n many ways, ORANGE/BLUE MARBLED 180 GR. VINYL Def Leppard were the definitive hard rock band of the ‘80s. There were groups that rocked harder, but few captured the spirit of the times quite as well. Emerging in the late ‘70s as part of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, Def Leppard gained a following outside of that scene by toning down their heavy riffs and emphasizing melody. In The Many Faces of Def Leppard, we are going to dig deep into the lesser known work of their members, collaborations, side projects and of course, their hit-filled catalog. LP1 - THE MANY FACES OF DEF LEPPARD LP2 - THE SONGS Side A Side A ALL JOIN HANDS - ROADHOUSE FEAT. PETE WILLIS & FRANK NOON POUR SOME SUGAR ON ME - LEE THOMPSON, JOHNNY DEE, RICHARD KENDRICK, I WILL BE THERE - GOMAGOG FEAT. PETE WILLIS & JANICK GERS MARKO PUKKILA & HOWIE SIMON DOIN’ FINE - CARMINE APPICE FEAT. VIVIAN CAMPBELL HYSTERIA - DANIEL FLORES ON A LONELY ROAD - THE FROG & THE RICK VITO BAND LET IT GO - WICKED GARDEN FEAT. JOE ELLIOTT ROCK ROCK TIL YOU DROP - CHRIS POLAND, JOE VIERS & RICHARD KENDRICK OVER MY DEAD BODY - MAN RAZE FEAT. -

Def Leppard “Hysteria” By: Kyle Harman

Def Leppard “Hysteria” By: Kyle Harman Hysteria would be a fitting name for the album thought Def Leppard drummer Rick Allen, following his 1984 injury from a horrific car accident that resulted in the loss of his left arm, Hysteria was the perfect title to describe the worldwide media coverage that followed the band between the years of 1984 and 1987. The album was the last to feature the late Steve Clark and his role of lead guitarist due to an overdose in the year of 1992. In the very prime years of glam metal in the late 80’s at the dawn of grunge genre about to begin, Def Leppard delivered the bands bestselling album to date with selling 25 million copies worldwide and 12 million in the US alone. The three year recording process of Hysteria was painstaking with the accident of drummer Rick Allen, and with producers coming and going left the band with the perfect example of sometimes patience truly does pay off. A unique recording process took place where each member recorded their own recordings at separate times, allowing each member to focus on their own performance on the album. The original intent of the album was to be a rock version of Michael Jackson’s Thriller, with the desire of having every song off the album as a possible hit single. The end result of the album was impressive to say the least with 7 singles released off the single album alone. The album recording sessions were painstaking at times, “Animal” consisted of 2 and a half years to produce its final product, where “Pour Some Sugar On Me” was finished within two weeks. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

1. Rush - Tom Sawyer 2

1. Rush - Tom Sawyer 2. Black Sabbath - Iron Man 3. Def Leppard - Photograph 4. Guns N Roses - November Rain 5. Led Zeppelin - Stairway to Heaven 6. AC/DC - Highway To Hell 7. Aerosmith - Sweet Emotion 8. Metallica - Enter Sandman 9. Nirvana - All Apologies 10. Black Sabbath - War Pigs 11. Guns N Roses - Paradise City 12. Tom Petty - Refugee 13. Journey - Wheel In The Sky 14. Led Zeppelin - Kashmir 15. Jimi Hendrix - All Along The Watchtower 16. ZZ Top - La Grange 17. Pink Floyd - Another Brick In The Wall 18. Black Sabbath - Paranoid 19. Soundgarden - Black Hole Sun 20. Motley Crue - Home Sweet Home 21. Derek & The Dominoes - Layla 22. Rush - The Spirit Of Radio 23. Led Zeppelin - Rock And Roll 24. The Who - Baba O Riley 25. Foreigner - Hot Blooded 26. Lynyrd Skynyrd - Freebird 27. ZZ Top - Cheap Sunglasses 28. Pearl Jam - Alive 29. Dio - Rainbow In The Dark 30. Deep Purple - Smoke On The Water 31. Nirvana - In Bloom 32. Jimi Hendrix - Voodoo Child (Slight Return) 33. Billy Squier - In The Dark 34. Pink Floyd - Wish You Were Here 35. Rush - Working Man 36. Led Zeppelin - Whole Lotta Love 37. Black Sabbath - NIB 38. Foghat - Slow Ride 39. Def Leppard - Armageddon It 40. Boston - More Than A Feeling 41. AC/DC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 42. Ozzy Osbourne - Crazy Train 43. Aerosmith - Walk This Way 44. Led Zeppelin - Dazed & Confused 45. Def Leppard - Rock Of Ages 46. Ozzy Osbourne - No More Tears 47. Eric Clapton - Cocaine 48. Ted Nugent - Stranglehold 49. Aerosmith - Dream On 50. Van Halen - Eruption / You Really Got Me 51. -

Def Leppard Headline Grand Opening Concert

DEF LEPPARD TO HEADLINE GRAND OPENING CONCERT FOR HARD ROCK HOTEL & CASINO SACRAMENTO AT FIRE MOUNTAIN DEF LEPPARD WITH DON FELDER AND LAST IN LINE SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 2ND TOYOTA AMPHITHEATRE Tickets On Sale Friday, September 13 at 10am at LiveNation.com Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Sacramento at Fire Mountain Set to Open on October 30 SACRAMENTO, Calif. – Sept. 6, 2019 – With great anticipation, Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Sacramento at Fire Mountain announces the property will open its doors the evening of Wednesday, October 30, with grand opening celebrations occurring all weekend. The official opening will kick off with a world-famous Hard Rock guitar smash; and in true Hard Rock fashion, Def Leppard will perform on Saturday, November 2 at Toyota Amphitheatre with special guests Don Felder and Last in Line to commemorate the opening. On Sunday, November 3 guests can experience some of the most exciting marketing promotions and events in the marketplace. “We’ve been looking forward to opening our doors since we broke ground in July 2018,” said Mark Birtha, president of Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Sacramento at Fire Mountain. “Hard Rock is passionate about providing world-class service in amazingly designed venues to create authentic experiences that rock. We’re excited for our guests to experience all of that and many more surprises here in Northern California. This milestone has been made possible through our relationships with local businesses and contractors, the dedication of 1,300 team members, and the vision, commitment and hard work of the Enterprise Rancheria Tribe.” Do you want to get Rocked! On Saturday, November 2, BRITISH ICONS Def Leppard will rock the stage as the Hard Rock’s grand opening performance at Toyota Amphitheatre next door. -

Ef Eppard in 19 Formation: Ste E Clark, Phil Collen, Oe Lliott, Rick Sa Ae, and Rick Llen

ef eppard in 19 formation: Stee Clark, Phil Collen, oe lliott, Rick Saae, and Rick llen (from left) > Def > 20494_RNRHF_Text_Rev1_22-61.pdf 9 3/11/19 5:23 PM 21333_RNRHF_DefLeppard_30-37_ACG.inddLeppard 30 4/25/19 4:11 PM A THEY FORGED A NEW POP-METAL SOUND WITH MULTIPLATINUM RESULTS BY ROBERT BURKE WARREN issing his bus that autumn day States. Their club-mates: Van Halen, Led Zeppelin, in Sheeld, England, 1977, may Pink Floyd, the Eagles, and the Beatles. But while the have inconvenienced 18-year- band’s journey includes these and many other strato- old wannabe rocker Joe Elliott, spheric highs of rock stardom, it also features some but it set in motion a series of unimaginable lows – legendary dues paying, it seems, events that would lead to his for all those dreams come true. fronting one of the biggest Looking back to the murky beginnings, Elliott re- bands in history: Def Leppard. An undeniable eight- called passing 19-year-old local guitar player Pete ies juggernaut still vital today, Def Leppard stand as Willis on that unplanned walk home from the bus one of a handful of rock bands to reach the RIAA’s stop. It was, he said, “a sliding-doors moment.” Elliott “Double Diamond” status, i.e., ten million units of had just taken up guitar and asked if Willis’ new Mtwo or more original studio albums sold in the United metal band, Atomic Mass – which included drummer 21333_RNRHF_DefLeppard_30-37_ACG.indd 31 4/25/19 4:11 PM Pete Willis, Allen, Elliott, Clark, and Savage (clockwise from bottom), before a gig at Atlanta’s Fox Theatre, 1981 20494_RNRHF_Text_Rev1_22-61.pdf 11 3/11/19 5:23 PM Above: Elliott surprised by Union Jack-ed fans, c. -

Program Abstracts

ProgramAddressing the Abstracts: Needs of at-Risk Youth in Public Schools and After-school Programs Abigail A. Allen “Efficacy of a Peer Tutoring Application for Word Reading for Early Elementary Students in a Rural High-Poverty School” Students with reading disabilities receive most of their instruction in the general education setting (U.S. Department of Education, 2018), so elementary educators can expect to have students with or at risk for reading disabilities in their classrooms. This study investigated the effectiveness of a peer tutoring iPad app with auditory prompting on the high frequency word reading of early elementary students. Participants (n = 106; 74 first grade, 32 kindergarten) from one high-poverty (77% eligible for free/reduced lunch) rural elementary school in the Southeast were randomly assigned to either the intervention condition, where they used the peer tutor app with a partner for 10 minutes 3 times per week for 6 weeks, or the comparison condition. Results indicated lower performing readers in the intervention group significantly improved their reading of early high frequency words compared to the comparison group and that the app shows promise to provide support to young struggling readers. Antonis Katsiyannis “National Analysis of the Disciplinary Exclusion of Black Students with and without Disabilities” Using rates and risk ratios, the current study sought to determine the current national results regarding school discipline for Black students. Results indicated that approximately 10% of Black students received a suspension, compared with 2.5% for all other racial/ethnic groups. For students with disabilities, approximately 23% of Black students received a suspension, compared with approximately 9% for Hispanic and White students with disabilities, almost 6% for Asian students with disabilities, and 21% for Native American students with disabilities. -

Def Leppard Announce Select Fall 20/20 Vision Tour Dates with Very Special Guests Zz Top

DEF LEPPARD ANNOUNCE SELECT FALL 20/20 VISION TOUR DATES WITH VERY SPECIAL GUESTS ZZ TOP 16-City Tour to Kick Off on September 21st Tickets On Sale To General Public Starting Friday, February 21 at LiveNation.com (NEW YORK - NY February 13, 2020) – Legendary British rock’ & roll icons, and 2019 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame® inductees, Def Leppard, announce select 20/20 Vision fall tour dates with very special guests ZZ Top. Produced by Live Nation, this new leg of dates will immediately follow the group’s massively successful summer stadium tour with Motley Crue, which has already sold 1.1 million tickets. The 20/20 Vision tour will kick off on September 21st at Times Union Center in Albany, NY. Please see full tour routing below. Tickets go on sale to the general public beginning Friday, February 21st at 10am local time at LiveNation.com. Citi is the official presale credit card of the 20/20 Vision Tour. As such, Citi cardmembers will have access to purchase presale tickets beginning Tuesday, February 18th at 10am local time until Thursday, February 20th at 10pm local time through Citi Entertainment®. For complete presale details visit www.citientertainment.com. Def Leppard front man Joe Elliott says of the tour, “What a year this is going to be! First, sold out stadiums, then we get to go on tour with the mighty ZZ Top! Having been an admirer of the band for a lifetime it’s gonna be a real pleasure to finally do some shows together...maybe some of us will get to go for a spin with Billy in one of those fancy cars ...” “We’re excited about hitting the road with Def Leppard this fall; we’ve been fans of theirs since forever,” says the aforementioned Billy F Gibbons. -

The Totally 80S Karaoke Song List! Alpha by Artist

The Totally 80s Karaoke Song List! Alpha by Artist Disc # Artist Song J 89 10000 Maniacs Like The Weather D 229 38Special Hold On Loosely H 229 A Ha Take On Me H 645 Abba Super Trouper A 520 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long D 198 AC/DC Back In Black D 188 AC/DC Hells Bells H 38 Adam Ant Goody Two Shoes F2 1 Aerosmith Dude Looks Like a Lady F2 2 Aerosmith Love in an Elevator D 967 Aerosmith Walk This Way H 315 Air Supply All Out Of Love H 1124 Air Supply Lost In Love A 41 Alabama Mountain Music G 744 Alan Jackson Here In The Real World A 130 AlannahMyles Black Velvet D 118 Alice Cooper Generation Landslide D 777 AlJarreau After All H 1024 Amy Grant El Shaddai H 1000 Amy Grant / Peter Cetera Next Time I Fall H 1165 Anita Baker Caught Up In The Rapture A 652 AnitaBaker Sweet Love G 1076 Atlantic Star Always H 251 Atlantic Star Secret Lovers B 126 Atlantic Starr Always H 1200 Atlantic Starr Masterpiece H 245 B. Segar / Silver Bul. Against The Wind D 1179 B52's Love Shack H 185 B-52's Roam H 254 Bad English When I See You Smile A 337 Bananarama Venus H 187 Bananarama Cruel Summer D 902 Bangles Eternal Flame D 1201 Bangles Manic Monday A 339 Bangles Walk Like An Egyptian D 1139 Barbra Streisand Memory D 1106 Barbra Streisand People J 76 Barbra Streisand/Barry GibbGuilty H 282 Berlin Take My Breath Away G 714 Bertie Higgins Just Another Day In Paradise D 1067 Bette Midler Wind Beneath My Wings, The A 561 Billy Idol Cradle Of Love E2 15 Billy Idol Rebel Yell H 1228 Billy Idol White Wedding A 336 Billy Joel It's Still Rock And Roll To Me A 321 -

The GAVIN REPORT

GAVIN SALUTES BLACK MUSIC MONTH the GAVIN REPORT TEDDY PENDERGRASS TALKS ABOUT HIS MESSAGE OF LOVE AND JOY www.americanradiohistory.com BOOM' THERE SHE WAS SCRJTTI POLITY FEATURI \G ROGEF ON VOICE BOX THE NEW S FROM THE ALBUM P R 0 V I S I 0 1` PRODUCED BY GREEN GARTSIDE AND DAVID GAMS0] MANAGEMENT: PARTISAN MANAGEMENT LTD. © 1988 JOUISSANCE (UK) LTI www.americanradiohistory.com the GAVIN REPORT TOP 40 MOST ADDED IMMIEM GLORIA ESTEFAN & MSM (122) 1 1 1 GEORGE MICHAEL - One More Try (Columbia) (Epic) CHICAGO (120) 7 5 2 RICK ASTLEY - Together Forever (RCA) (Full Moon/Reprise) 6 3 3 Daryl Hall & John Oates - Everything Your Heart Desires (Arista) AEROSMITH (90) (Geffen) 2 2 4 Johnny Hates Jazz - Shattered Dreams (Virgin) TERENCE TRENT D'ARBY (76) 8 (Columbia) 12 5 DEBBIE GIBSON - Foolish Beat (Atlantic) BILLY OCEAN (71) 19 15 6 MICHAEL JACKSON - Dirty Diana (Epic) (Jive /Arista) COREY HART (70) 11 10 7 BELINDA CARLISLE - Circle In The Sand (MCA) (EMI -Manhattan) 16 12 8 CHEAP TRICK - The Flame BREATHE (53) (Epic) (A&M) 17 16 9 BRUCE HORNSBY & THE RANGE - The Valley Road (RCA) 18 17 10 THE JETS - Make It Real (MCA) CERTIFIED 14 11 CHER - We All Sleep Alone (Geffen) 23 19 12 LITA FORD - Kiss Me Deadly (Dreamland /RCA) RICHARD MARX 9 11 Hold On To The Nights 13 Samantha Fox - Naughty Girls (Need Love Too) (Jive /RCA) (EMI -Manhattan) 24 20 14 PRINCE - Alphabet St. (Paisley Park/Warner Bros.) BREATHE 14 13 15 Times Two - Strange But True (Reprise) Hands To Heaven 4 6 16 Foreigner - I Don't Want (A8M) To Live Without You (Atlantic) 3 7 17 Gloria Estefan & MSM - Anything For You (Epic) 24 18 POISON - Nothin' But A Good Time (Enigma/Capitol) RECORD ió 19 The Deele - Two Occasions (Solar /Capitol) TO WATCH 35 20 DEF LEPPARD - Pour Some Sugar On Me (Mercury/PolyGram) 32 21 INXS - New Sensation (Atlantic) 33 27 22 MIDNIGHT OIL - Beds Are Burning (Columbia) 32 26 23 THE CHURCH - Under The Milky Way (Arista) 34 29 24 BRENDA K.STARR - I Still Believe (MCA) 37 25 PEBBLES - Mercedes Boy (MCA) 37 33 26 ROD STEWART - Lost In You (Warner Bros.) 39 34 27 AL B.