Redalyc.Spoilage and Pathogenic Bacteria Isolated from Two Types Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

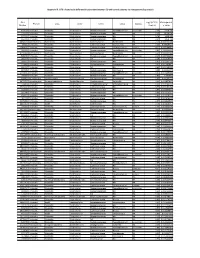

Appendix III: OTU's Found to Be Differentially Abundant Between CD and Control Patients Via Metagenomeseq Analysis

Appendix III: OTU's found to be differentially abundant between CD and control patients via metagenomeSeq analysis OTU Log2 (FC CD / FDR Adjusted Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Number Control) p value 518372 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.16 5.69E-08 194497 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.15 8.93E-06 175761 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 5.74 1.99E-05 193709 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.40 2.14E-05 4464079 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 7.79 0.000123188 20421 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae Coprococcus NA 1.19 0.00013719 3044876 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae [Ruminococcus] gnavus -4.32 0.000194983 184000 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.81 0.000306032 4392484 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 5.53 0.000339948 528715 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.17 0.000722263 186707 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.28 0.001028539 193101 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 1.90 0.001230738 339685 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Peptococcaceae Peptococcus NA 3.52 0.001382447 101237 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.64 0.001415109 347690 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Oscillospira NA 3.18 0.00152075 2110315 Firmicutes Clostridia -

Clostridioides Difficileinfections

bioMérieux In vitro diagnostics serving CLOSTRIDIOIDES public health DIFFICILE INFECTIONS A major player in in vitro diagnostics for more than 50 years, From Diagnosis to bioMérieux has always been driven by a pioneering spirit and unrelenting commitment to improve public health worldwide. Outbreak Management Our diagnostic solutions bring high medical value to healthcare professionals, providing them with the most relevant and reliable information, as quickly as possible, to support treatment decisions and better patient care. bioMérieux’s mission entails a commitment to support medical education, by promoting access to diagnostic knowledge for as many people as possible. Focusing on the medical value of diagnostics, our collection of educational booklets aims to raise awareness of the essential role that diagnostic test results play in healthcare decisions. Other educational booklets are available. Consult your local bioMérieux representative. The information in this booklet is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be exhaustive. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a medical director, physician, or other qualified health provider regarding processes and/or protocols for diagnosis and treatment of a medical condition. bioMérieux assumes no responsibility or liability for any diagnosis established or treatment prescribed by the physician. bioMérieux, Inc. • 100 Rodolphe Street • Durham, NC 27712 • USA • Tel: (800) 682 2666 • Fax: (800) 968 9494 © 2019 bioMérieux, Inc. • BIOMERIEUX and the BIOMERIEUX logo, are used pending and/or registered trademarks belonging to bioMérieux, or one of its subsidiaries, or one of its companies. companies. its or one of subsidiaries, its or one of bioMérieux, belonging to trademarks registered pending and/or used are logo, and the BIOMERIEUX • BIOMERIEUX Inc. -

Efficacy of Clostridium Bifermentans Serovar Malaysia on Target and Nontarget Organisms

Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association, lO(I):51-55,1994 Copyright @ 1994 by the American Mosquito Control Association, Inc. EFFICACY OF CLOSTRIDIUM BIFERMENTANS SEROVAR MALAYSIA ON TARGET AND NONTARGET ORGANISMS M. YIALLOUROS,T V. STORCH,: I. THIERYT erp N. BECKERI ABSTRACT. Clostridium bifermentansserovar malaysia (C.b.m.) is highly toxic to mosquito larvae. In this study, the following aquatic nontarget invertebrateswere treated with high C.b.,,?.concentrations (up to 1,600-fold the toxic concentration for Anophelesstephensi) to study their susceptibility towards the bacterial toxrn: Planorbis planorbis (Pulmonata); Asellus aquaticzs (Isopoda); Daphnia pulex (Cla- docera);Cloeon dipterun (Ephemeroptera);Plea leachi (Heteroptera);and Eristalis sp., Chaoboruscrys' tallinus, Chironomus thummi, and Psychodaalternata (Diptera). In addition, bioassayswere performed with mosquito Larvae(Aedes aegypti, Anopheles stephensi, and Culex pipiens). Psychodaalternatalamae were very susc€ptible,with LCro/LCro values comparable to those of mosquito larvae (about 103-105 spores/ml). The tests with Chaoboruscrystallinus larvae showed significant mortality rates at high con- centrations,but generallynot before 4 or 5 days after treatment. The remaining nontargetorganisms did not show any susceptibility.The investigation confirms the specificityof C.b.m.lo nematocerousDiptera. INTRODUCTION strains of Aedesaegypti (Linn ) larvae, which are about I 0 times lesssensitiv e than A nophe I e s. The For several years, 2larvicidal bacteia, Bacil- LCr' (48 h) rangesfrom 5 x 103to 2 x lOscells/ lus thuringiensls Berliner var. israelensis (B.t.i.) ml (Thiery et al. 1992b).Larvae of Simulium and Bacillus sphaericus Neide, have been used speciesseem to be less susceptible(de Barjac et successfully for mosquito and blackfly control all al. -

Germinants and Their Receptors in Clostridia

JB Accepted Manuscript Posted Online 18 July 2016 J. Bacteriol. doi:10.1128/JB.00405-16 Copyright © 2016, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved. 1 Germinants and their receptors in clostridia 2 Disha Bhattacharjee*, Kathleen N. McAllister* and Joseph A. Sorg1 3 4 Downloaded from 5 Department of Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843 6 7 Running Title: Germination in Clostridia http://jb.asm.org/ 8 9 *These authors contributed equally to this work 10 1Corresponding Author on September 12, 2018 by guest 11 ph: 979-845-6299 12 email: [email protected] 13 14 Abstract 15 Many anaerobic, spore-forming clostridial species are pathogenic and some are industrially 16 useful. Though many are strict anaerobes, the bacteria persist in aerobic and growth-limiting 17 conditions as multilayered, metabolically dormant spores. For many pathogens, the spore-form is Downloaded from 18 what most commonly transmits the organism between hosts. After the spores are introduced into 19 the host, certain proteins (germinant receptors) recognize specific signals (germinants), inducing 20 spores to germinate and subsequently outgrow into metabolically active cells. Upon germination 21 of the spore into the metabolically-active vegetative form, the resulting bacteria can colonize the 22 host and cause disease due to the secretion of toxins from the cell. Spores are resistant to many http://jb.asm.org/ 23 environmental stressors, which make them challenging to remove from clinical environments. 24 Identifying the conditions and the mechanisms of germination in toxin-producing species could 25 help develop affordable remedies for some infections by inhibiting germination of the spore on September 12, 2018 by guest 26 form. -

Staphylococcus Aureus Kentaro Iwata1*, Asako Doi2, Takahiko Fukuchi1, Goh Ohji1, Yuko Shirota3, Tetsuya Sakai4 and Hiroki Kagawa5

Iwata et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2014, 14:247 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/14/247 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access A systematic review for pursuing the presence of antibiotic associated enterocolitis caused by methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus Kentaro Iwata1*, Asako Doi2, Takahiko Fukuchi1, Goh Ohji1, Yuko Shirota3, Tetsuya Sakai4 and Hiroki Kagawa5 Abstract Background: Although it has received a degree of notoriety as a cause for antibiotic-associated enterocolitis (AAE), the role of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in the pathogenesis of this disease remains enigmatic despite a multitude of efforts, and previous studies have failed to conclude whether MRSA can cause AAE. Numerous cases of AAE caused by MRSA have been reported from Japan; however, due to the fact that these reports were written in the Japanese language and a good portion lacked scientific rigor, many of these reports went unnoticed. Methods: We conducted a systematic review of pertinent literatures to verify the existence of AAE caused by MRSA. We modified and applied methods in common use today and used a total of 9 criteria to prove the existence of AAE caused by Klebsiella oxytoca. MEDLINE/Pubmed, Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the Japan Medical Abstract Society database were searched for studies published prior to March 2013. Results: A total of 1,999 articles were retrieved for evaluation. Forty-five case reports/series and 9 basic studies were reviewed in detail. We successfully identified articles reporting AAE with pathological and microscopic findings supporting MRSA as the etiological agent. We also found comparative studies involving the use of healthy subjects, and studies detecting probable toxins. -

Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Anaerobic

antibiotics Review Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Anaerobic Bacteria: Rubik’s Cube of Clinical Microbiology? Márió Gajdács 1,*, Gabriella Spengler 1 and Edit Urbán 2 1 Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunobiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Szeged, 6720 Szeged, Hungary; [email protected] 2 Institute of Clinical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Szeged, 6725 Szeged, Hungary; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +36-62-342-843 Academic Editor: Leonard Amaral Received: 28 September 2017; Accepted: 3 November 2017; Published: 7 November 2017 Abstract: Anaerobic bacteria have pivotal roles in the microbiota of humans and they are significant infectious agents involved in many pathological processes, both in immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals. Their isolation, cultivation and correct identification differs significantly from the workup of aerobic species, although the use of new technologies (e.g., matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, whole genome sequencing) changed anaerobic diagnostics dramatically. In the past, antimicrobial susceptibility of these microorganisms showed predictable patterns and empirical therapy could be safely administered but recently a steady and clear increase in the resistance for several important drugs (β-lactams, clindamycin) has been observed worldwide. For this reason, antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic isolates for surveillance -

Characterization of an Endolysin Targeting Clostridioides Difficile

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Characterization of an Endolysin Targeting Clostridioides difficile That Affects Spore Outgrowth Shakhinur Islam Mondal 1,2 , Arzuba Akter 3, Lorraine A. Draper 1,4 , R. Paul Ross 1 and Colin Hill 1,4,* 1 APC Microbiome Ireland, University College Cork, T12 YT20 Cork, Ireland; [email protected] (S.I.M.); [email protected] (L.A.D.); [email protected] (R.P.R.) 2 Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology Department, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet 3114, Bangladesh 3 Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Department, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet 3114, Bangladesh; [email protected] 4 School of Microbiology, University College Cork, T12 K8AF Cork, Ireland * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Clostridioides difficile is a spore-forming enteric pathogen causing life-threatening diarrhoea and colitis. Microbial disruption caused by antibiotics has been linked with susceptibility to, and transmission and relapse of, C. difficile infection. Therefore, there is an urgent need for novel therapeutics that are effective in preventing C. difficile growth, spore germination, and outgrowth. In recent years bacteriophage-derived endolysins and their derivatives show promise as a novel class of antibacterial agents. In this study, we recombinantly expressed and characterized a cell wall hydrolase (CWH) lysin from C. difficile phage, phiMMP01. The full-length CWH displayed lytic activity against selected C. difficile strains. However, removing the N-terminal cell wall binding domain, creating CWH351—656, resulted in increased and/or an expanded lytic spectrum of activity. C. difficile specificity was retained versus commensal clostridia and other bacterial species. -

Synergistic Haemolysis Test for Presumptive Identification and Differentiation of Clostridium Perfringens, C

J Clin Pathol: first published as 10.1136/jcp.33.4.395 on 1 April 1980. Downloaded from J Clin Pathol 1980; 33: 395-399 Synergistic haemolysis test for presumptive identification and differentiation of Clostridium perfringens, C. bifermentans, C. sordeilhi, and C. paraperfringens STEVAN M GUBASH From the Department ofPathology, Division of Medical Microbiology, Kingston General Hospital, Kingston, Ontario, Canada K7L 2 V7, and the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada K7L 3N6 SUMMARY A new test for the presumptive identification of Clostridium perfringens, C. bifermentans, C. sordellii, and C. paraperfringens is described. The test is based on the synergistic haemolysis shown by the clostridia and group B streptococci on sheep and human and CaCl2-supplemented human blood agar. C. perfringens gave crescent-shaped synergistic lytic zones (7 to over 10 mm in length), and C. paraperfringens usually small-sized (3 mm), bullet-shaped reactions on all three types of media. C. bifermentans showed a horseshoe-shaped synergistic reaction only on human blood containing media, and C. sordellii only on CaCl2-supplemented human blood agar. C. perfringens type A antiserum inhibited synergistic lytic activities of the four species. The test provided a reliable method for presumptive identification and differentiation of the four clostridial species and may obviate the need for the Nagler test. http://jcp.bmj.com/ Most clinical microbiology laboratories use the genically related phospholipase C. The test is based Nagler test 2 3 for presumptive identification of on the synergistic haemolysis due to the interaction Clostridium perfringens and other phospholipase C of the CAMP-factor of group B streptococci and (lecithinase C) producing clostridia. -

Clostridial Diseases of Cattle

Clostridial Diseases of Cattle Item Type text; Book Authors Wright, Ashley D. Publisher College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Download date 01/10/2021 18:20:24 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/625416 AZ1712 September 2016 Clostridial Diseases of Cattle Ashley Wright Vaccinating for clostridial diseases is an important part of a ranch health program. These infections can have significant Sporulating bacteria, such as Clostridia and Bacillus, economic impacts on the ranch due to animal losses. There form endospores that protect bacterial DNA from extreme are several diseases caused by different organisms from the conditions such as heat, cold, dry, UV radiation, and some genus Clostridia, and most of these are preventable with a disinfectants. Unlike fungal spores, these spores cannot sound vaccination program. Many of these infections can proliferate; they are dormant forms of the bacteria that allow progress very rapidly; animals that were healthy yesterday survival until environmental conditions are ideal for growth. are simply found dead with no observed signs of sickness. In most cases treatment is difficult or impossible, therefore we absence of oxygen to survive. Clostridia are one genus of rely on vaccination to prevent infection. The most common bacteria that have the unique ability to sporulate, forming organisms included in a 7-way or 8-way clostridial vaccine microscopic endospores when conditions for growth and are discussed below. By understanding how these diseases survival are less than ideal. Once clostridial spores reach a occur, how quickly they can progress, and which animals are suitable, oxygen free, environment for growth they activate at risk you will have a chance to improve your herd health and return to their bacterial (vegetative) state. -

Clostridioides Difficile Infection in Adults and Children

Guidelines for Clinical Care Quality Department Clostridioides difficile Infection Guideline Team Clostridioides difficile Infection Team Leads in Adults and Children Tejal N Gandhi MD Infectious Diseases Patient population: Adults and children with a primary or recurrent episode of Clostridioides Krishna Rao, MD difficile infection (CDI). Infectious Diseases Team Members Objectives: Gregory Eschenauer, PharmD 1. Provide a brief overview of the epidemiology of, and risk factors for development Pharmacy of CDI. John Y Kao, MD 2. Provide guidance regarding which patients should be tested for CDI, summarize merits and Gastroenterology limitations of available diagnostic tests, and describe the optimal approach to laboratory diagnosis. Lena M Napolitano, MD 3. Review the most effective treatment strategies for patients with CDI including patients with Surgery recurrences or complications. F Jacob Seagull, PhD Leaning Heath Sciences Key Points for Adult Patients: David M Somand, MD Emergency Medicine Diagnosis Alison C Tribble, MD Definitive diagnosis of CDI requires either the presence of toxigenic C. difficile in stool with Pediatric Infectious Diseases compatible symptoms, or clinical evidence of pseudomembranous colitis (Table 2, Figure 4). Amanda M Valyko, MPH, CIC Once identified, CDI should be classified according to severity (Table 3). Infection Control Although risk factors for CDI (Table 1) should guide suspicion for CDI, testing should be ordered Michael E Watson Jr, MD, only when indicated (Figure 1). Use judgment and consider not testing in patients that have PhD recently started tube feeds, are taking a laxative medication, or have recently received oral Pediatric Infectious Diseases radiologic contrast material. [IC] Consultants: Choice of test should be guided by a multi-step algorithm for the rapid diagnosis of CDI (Figure 2). -

Porphyromonas Gingivalis and Treponema Denticola Exhibit Metabolic Symbioses

Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola Exhibit Metabolic Symbioses Kheng H. Tan1., Christine A. Seers1., Stuart G. Dashper1., Helen L. Mitchell1, James S. Pyke1, Vincent Meuric1, Nada Slakeski1, Steven M. Cleal1, Jenny L. Chambers2, Malcolm J. McConville2, Eric C. Reynolds1* 1 Oral Health CRC, Melbourne Dental School, Bio21 Institute, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, 2 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Bio21 Institute, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia Abstract Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola are strongly associated with chronic periodontitis. These bacteria have been co-localized in subgingival plaque and demonstrated to exhibit symbiosis in growth in vitro and synergistic virulence upon co-infection in animal models of disease. Here we show that during continuous co-culture a P. gingivalis:T. denticola cell ratio of 6:1 was maintained with a respective increase of 54% and 30% in cell numbers when compared with mono- culture. Co-culture caused significant changes in global gene expression in both species with altered expression of 184 T. denticola and 134 P. gingivalis genes. P. gingivalis genes encoding a predicted thiamine biosynthesis pathway were up- regulated whilst genes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis were down-regulated. T. denticola genes encoding virulence factors including dentilisin and glycine catabolic pathways were significantly up-regulated during co-culture. Metabolic labeling using 13C-glycine showed that T. denticola rapidly metabolized this amino acid resulting in the production of acetate and lactate. P. gingivalis may be an important source of free glycine for T. denticola as mono-cultures of P. gingivalis and T. denticola were found to produce and consume free glycine, respectively; free glycine production by P. -

Depression and Microbiome—Study on the Relation and Contiguity Between Dogs and Humans

applied sciences Article Depression and Microbiome—Study on the Relation and Contiguity between Dogs and Humans Elisabetta Mondo 1,*, Alessandra De Cesare 1, Gerardo Manfreda 2, Claudia Sala 3 , Giuseppe Cascio 1, Pier Attilio Accorsi 1, Giovanna Marliani 1 and Massimo Cocchi 1 1 Department of Veterinary Medical Science, University of Bologna, Via Tolara di Sopra 50, 40064 Ozzano Emilia, Italy; [email protected] (A.D.C.); [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (P.A.A.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (M.C.) 2 Department of Agricultural and Food Sciences, University of Bologna, Via del Florio 2, 40064 Ozzano Emilia, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Alma Mater Studiorum, University of Bologna, 40126 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-051-209-7329 Received: 22 November 2019; Accepted: 7 January 2020; Published: 13 January 2020 Abstract: Behavioral studies demonstrate that not only humans, but all other animals including dogs, can suffer from depression. A quantitative molecular evaluation of fatty acids in human and animal platelets has already evidenced similarities between people suffering from depression and German Shepherds, suggesting that domestication has led dogs to be similar to humans. In order to verify whether humans and dogs suffering from similar pathologies also share similar microorganisms at the intestinal level, in this study the gut-microbiota composition of 12 German Shepherds was compared to that of 15 dogs belonging to mixed breeds which do not suffer from depression. Moreover, the relation between the microbiota of the German Shepherd’s group and that of patients with depression has been investigated.