Clostridial Diseases of Cattle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clostridial Septicemia with Intravascular Hemolysis: a Case Report G

Henry Ford Hospital Medical Journal Volume 13 | Number 4 Article 4 12-1965 Clostridial Septicemia With Intravascular Hemolysis: A Case Report G. M. Mastio E. Morfin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.henryford.com/hfhmedjournal Part of the Life Sciences Commons, Medical Specialties Commons, and the Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Mastio, G. M. and Morfin, E. (1965) "Clostridial Septicemia With Intravascular Hemolysis: A Case Report," Henry Ford Hospital Medical Bulletin : Vol. 13 : No. 4 , 421-425. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.henryford.com/hfhmedjournal/vol13/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Henry Ford Health System Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Henry Ford Hospital Medical Journal by an authorized editor of Henry Ford Health System Scholarly Commons. Henry Ford Hosp. Med. Bull. Vol. 13, December 1965 CLOSTRIDIAL SEPTICEMIA WITH INTRAVASCULAR HEMOLYSIS A CASE REPORT G. M. MASTIC, M.D. AND E. MORFIN, M.D. In 1871 Bottini' demonstrated the bacterial nature of gas gangrene, but failed to isolate a causal organism. Clostridium perfringens, sometimes known as Clostridium welchii, was discovered independently during 1892 and 1893 by Welch, Frankel, "Veillon and Zuber.^ This organism is a saprophytic inhabitant of the intestinal tract, and may be a harmless saprophyte of the female genital tract occurring in the vagina in 4-6 per cent of pregnant women. Clostridial organisms occur in great numbers and distribution throughout the world. Because of this, they are very common in traumatic wounds. Very few species of Clostridia, however, are pathogenic, and still fewer are capable of producing gas gangrene in man. -

Naeglaria and Brain Infections

Can bacteria shrink tumors? Cancer Therapy: The Microbial Approach n this age of advanced injected live Streptococcus medical science and into cancer patients but after I technology, we still the recipients unfortunately continue to hunt for died from subsequent innovative cancer therapies infections, Coley decided to that prove effective and safe. use heat killed bacteria. He Treatments that successfully made a mixture of two heat- eradicate tumors while at the killed bacterial species, By Alan Barajas same time cause as little Streptococcus pyogenes and damage as possible to normal Serratia marcescens. This Alani Barajas is a Research and tissue are the ultimate goal, concoction was termed Development Technician at Hardy but are also not easy to find. “Coley’s toxins.” Bacteria Diagnostics. She earned her bachelor's degree in Microbiology at were either injected into Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo. The use of microorganisms in tumors or into the cancer therapy is not a new bloodstream. During her studies at Cal Poly, much idea but it is currently a of her time was spent as part of the undergraduate research team for the buzzing topic in cancer Cal Poly Dairy Products Technology therapy research. Center studying spore-forming bacteria in dairy products. In the late 1800s, German Currently she is working on new physicians W. Busch and F. chromogenic media formulations for Fehleisen both individually Hardy Diagnostics, both in the observed that certain cancers prepared and powdered forms. began to regress when patients acquired accidental erysipelas (cellulitis) caused by Streptococcus pyogenes. William Coley was the first to use New York surgeon William bacterial injections to treat cancer www.HardyDiagnostics.com patients. -

Sheep Diseases the FARMERS’ GUIDE 2Nd Edition - July 2015 Sheep Diseases the FARMERS’ GUIDE

Sheep Diseases THE FARMERS’ GUIDE 2nd Edition - July 2015 Sheep Diseases THE FARMERS’ GUIDE Developed by: Emily Litzow for Primary Industries and Regions South Australia, Biosecurity SA Animal Health Funded by: SA Sheep Industry Fund and Biosecurity SA Use of the information/advice in this guide is at your own risk. The Department of Primary Industries and Regions SA and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The entire risk of the implementation of the information/ advice which has been provided to you is assumed by you. All liability or responsibility to any person using the information/advice is expressly disclaimed by the Department of Primary Industries and Regions SA and its employees. 2 Acknowledgements and Further Reading The Information in this publication has been collected from: Allan, S 2010, Foot Abscess in Sheep, NSW DPI Primefact 7, NSW. Animal Biosecurity Unit 2008, Ovine Johne’s Disease, NSW DPI Primefact 661, NSW. Australian Animal Welfare Standards and Guidelines - Land Transport of Livestock, Animal Health Australia (AHA) 2012, Canberra. Brightling, A 2006, Livestock Diseases in Australia, C H Jerram and Associates Science Publishers, Australia. Butler, R 2008, Ovine Brucellosis, Department of Agriculture and Food Farmnote 334, WA. Chester, L 2010, Sheep Welfare – Avoiding Losses due to Hypothermia, Department of Agriculture and Food Farmnote 453, WA. Cotter, J 2011, Sheep Lice – Spread and Detection, Department of Agriculture and Food Farmnote 478, WA. Erickson, A 2010, Hydatid Disease, Department of Agriculture and Food Farmnote 448, WA. -

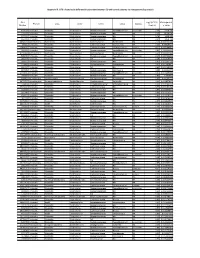

Appendix III: OTU's Found to Be Differentially Abundant Between CD and Control Patients Via Metagenomeseq Analysis

Appendix III: OTU's found to be differentially abundant between CD and control patients via metagenomeSeq analysis OTU Log2 (FC CD / FDR Adjusted Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Number Control) p value 518372 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.16 5.69E-08 194497 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.15 8.93E-06 175761 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 5.74 1.99E-05 193709 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 2.40 2.14E-05 4464079 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 7.79 0.000123188 20421 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae Coprococcus NA 1.19 0.00013719 3044876 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Lachnospiraceae [Ruminococcus] gnavus -4.32 0.000194983 184000 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.81 0.000306032 4392484 Bacteroidetes Bacteroidia Bacteroidales Bacteroidaceae Bacteroides NA 5.53 0.000339948 528715 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Faecalibacterium prausnitzii 2.17 0.000722263 186707 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.28 0.001028539 193101 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae NA NA 1.90 0.001230738 339685 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Peptococcaceae Peptococcus NA 3.52 0.001382447 101237 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales NA NA NA 2.64 0.001415109 347690 Firmicutes Clostridia Clostridiales Ruminococcaceae Oscillospira NA 3.18 0.00152075 2110315 Firmicutes Clostridia -

Blackleg and Clostridial Diseases

DIVISION OF AGRICULTURE RESEARCH & EXTENSION UJA--University of Arkansas System Agriculture and atural Resources FSA3073 Livestock Health eries Blackleg and Other Clostridial Diseases symptoms. Therefore, prevention of Heidi Ward, Introduction these diseases through immunization VM, Ph Clostridial bacteria cause several is more successful than trying to treat Assistant Professor diseases that affect cattle and other infected animals. and Veterinarian farm animals. This group of bacteria is known to produce toxins with varying effects based on the way they enter the Blackleg Jeremy Powell, body. The bacteria are frequently Blackleg, or clostridial myositis, VM, Ph found in the environment (primarily in affects cattle worldwide and is caused Professor the soil) and tend to multiply in warm by Clostridium chauvoei. Susceptible weather following heavy rain. The animals first ingest endospores. The bacteria are also found in the intes - endospores then cross over the gastro - tinal tracts of healthy farm animals, intestinal tract and enter the blood- where they only cause disease under stream where they are deposited in certain circumstances. The most muscle tissue in the animal’s body. common diseases caused by clostridial They then lie dormant in the tissue bacteria in beef cattle are blackleg, until they become activated and enterotoxemia, malignant edema, black trigger the disease. disease and tetanus. These diseases Clostridium chauvoei is activated are usually seen in young cattle (less in an anaerobic (oxygen deficient) than 2 years of age) and are widely environment such as damaged, distributed throughout Arkansas. devitalized or bruised tissue. Events Bacteria of the Clostridium genus such as transport, rough handling or produce long-lived structures called aggressive pasture activity can lead to endospores. -

Studies Upon the Blackleg Disease of the Potato, with Special Reference to the Rela- Tionship of the Causal Organisms

STUDIES UPON THE BLACKLEG DISEASE OF THE POTATO, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE RELA- TIONSHIP OF THE CAUSAL ORGANISMS By W. J. MORSE, Plant Pathologist, Maine Agricultural Experiment Station HISTORICAL REVIEW The fact that the potato (Solanum tuberosum) is subject to maladies like that under consideration in this paper was noted at a comparatively early date in the literature of bacterial diseases of plants. De Jubain- ville and Vesque (8)1 mentioned in 1878 a "cellular-rot" of potatoes, radishes, carrots, and beets as occurring in the soil and in cellars; but bacteria are not mentioned as the cause. Their paper and the one following are reviewed by Smith (32). In 1879 Reinke and Berthold (30) pointed out quite clearly that a wetrot of potatoes could occur without the presence of any fungi. According to Smith, they apparently did not have any active parasite and did not work with pure cultures. However, they were able to inoculate and cause a decay of healthy tubers by means of the watery fluid taken from diseased potatoes, provided especially favorable condi- tions were supplied in the line of moisture. They were also able to demonstrate the constant association of bacteria with the wetrotting of the tubers. Prillieux and Delacroix (28) described a disease of the potato stem from France in 1890 and gave the name "Bacillus caulivorus" to the organism which they considered to be the cause. Nothing is said in this paper as to the isolation of the organism and the growth of it in pure cultures, although later Prillieux (27, v. -

Phylogenetic Positions of Clostridium Novyi and Clostridium

International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2001), 51, 901–904 Printed in Great Britain Phylogenetic positions of Clostridium novyi NOTE and Clostridium haemolyticum based on 16S rDNA sequences 1 National Veterinary Assay Yoshimasa Sasaki,1 Noriyasu Takikawa,2 Akemi Kojima,1 Laboratory, 1-15-1, 3 1 1 Tokura, Kokubunji, Tokyo Mari Norimatsu, Shoko Suzuki and Yutaka Tamura 185-8511, Japan 2 Research Center for Author for correspondence: Yoshimasa Sasaki. Tel: j81 42 321 1841. Fax: j81 42 321 1769. Veterinary Science, The e-mail: sasakiy!nval.go.jp Kitasato Institute, 6-111, Arai, Kitamoto, Saitama, 364-0026, Japan The partial sequences (1465 bp) of the 16S rDNA of Clostridium novyi types A, B 3 Institute for Animal and C and Clostridium haemolyticum were determined. C. novyi types A, B and Health, Compton, Newbury RG20 7NN, UK C and C. haemolyticum clustered with Clostridium botulinum types C and D. Moreover, the 16S rDNA sequences of C. novyi type B strains and C. haemolyticum strains were completely identical; they differed by 1 bp (level of similarity S 999%) from that of C. novyi type C, they were 987% homologous to that of C. novyi type A (relative positions 28–1520 of the Escherichia coli 16S rDNA sequence) and they exhibited a higher similarity to the 16S rDNA sequence of C. botulinum types D and C than to that of C. novyi type A. These results suggest that C. novyi types B and C and C. haemolyticum may be one independent species generated from the same phylogenetic origin. Keywords: Clostridium novyi types A, B and C, Clostridium haemolyticum, 16S rRNA analysis Clostridium novyi is divided into three types, A, B and duction of alpha (necrotizing) toxin, observed only in C. -

Blackleg in Cattle: Current Understanding and Future Research Needs

Ciência Rural, Santa Maria, v.48:05,Blackleg e20170939,in cattle: current 2018 understanding and future research http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0103-8478cr20170939 needs. 1 ISSNe 1678-4596 MICROBIOLOGY Blackleg in cattle: current understanding and future research needs Rosangela Estel Ziech1* Leticia Trevisan Gressler2 Joachim Frey3 Agueda Castagna de Vargas1 1Departamento de Medicina Veterinária Preventiva, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM), 97105-900, Santa Maria, RS, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected]. *Corresponding author. 2Instituto Federal Farroupilha (IFFar), Frederico Westphalen, RS, Brasil. 3Institute of Veterinary Bacteriology, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. ABSTRACT: Blackleg is an endogenous acute infection that principally affects cattle, whose etiologic agent is the anaerobic bacterium Clostridium chauvoei. In recent years, the major virulence factors of C. chauvoei have been discovered and described. However, the pathogenesis of blackleg in cattle, and in particular, the movement of the pathogen from the point of entry to the affected tissues is not yet fully elucidated. Disease control is based on appropriate management and vaccination. This review summarizes the latest research findings that contribute toward the understanding of the disease in cattle, provide a foundation to preventive strategies, and identify future research needs. Key words: Clostridium chauvoei, sudden death, myonecrosis. Carbúnculo sintomático: compreensão atual e futuras necessidades de pesquisa RESUMO: O carbúnculo sintomático é uma infecção endógena, aguda, que acomete principalmente bovinos, cujo agente etiológico é a bactéria anaeróbica Clostridium chauvoei. Recentemente, os principais fatores de virulência do C. chauvoei foram descobertos e descritos. Contudo, a patogênese do carbúnculo sintomático em bovinos, especialmente a circulação do patógeno desde o ponto de entrada até os tecidos acometidos ainda não está completamente elucidada. -

Infective Endocarditis Caused by C. Sordellii: the First Case Report from India

Published online: 2021-05-19 THIEME 74 C.Case sordellii Report in Endocarditis Chaudhry et al. Infective Endocarditis Caused by C. sordellii: The First Case Report from India Rama Chaudhry1 Tej Bahadur1 Tanu Sagar1 Sonu Kumari Agrawal1 Nazneen Arif1 Shiv K. Choudhary2 Nishant Verma1 1Department of Microbiology, All India Institute of Medical Address for correspondence Dr. Rama Chaudhry, MD, Department Sciences, New Delhi, India of Microbiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, 2Department of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery, All India New Delhi 110029, India (e-mail: [email protected]). Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India J Lab Physicians 2021;13:74–76. Abstract Clostridium sordellii is a gram-positive anaerobic bacteria most commonly isolated Keywords from skin and soft tissue infection, penetrating injurious and intravenous drug abus- ► infective endocarditis ers. The exotoxins produced by the bacteria are associated with toxic shock syndrome. ► Clostridium sordellii We report here a first case of infective endocarditis due to C. sordellii from a female ► diagnosis patient with ventricular septal defect from India. Introduction admitted to the cardiothoracic vascular surgery ward of All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, India Anaerobes are major components of the normal micro- with complaints of worsening shortness of breath and pal- bial flora present on human skin and mucosa. Infections pitations. Patient reported having an episode of IE 3 months due to anaerobic bacteria are common, but they are dif- back for which she had been admitted to AIIMS and was ficult to isolate from infected sites and are often over- discharged after treatment. -

Blackleg ( Clostridium Chauvoei Infection) in Beef Calves: a Review and Presentation of Two Cases with Uncommon Pathologic Presentations

PEER REVIEWED Blackleg ( Clostridium chauvoei Infection) in Beef Calves: A Review and Presentation of Two Cases with Uncommon Pathologic Presentations 1 2 Russell F. Daly ·, DVM; Dale W. Miskimins1, DVM, MS; Roland G. Good , DVM; Thomas Stenberg', DVM 1Veterinary Science Department, South Dakota State University, Brookings, SD 57007 2Parker Veterinary Clinic, Parker, SD 57053-5661 3Volga Veterinary Clinic, Volga, SD 57071-2006 *Corresponding author: Russ Daly, 605-688-6589 Office, [email protected] Abstract laires sont bien connues et incluent des changements sous cutanes gelatineux et gazeux de meme que des Blackleg (Clostridium chauvoei infection) has long necroses musculaires bien demarquees. Des zones de been recognized as a cause of death in calves grazing necrose peuvent aussi etre presentes dans le myocarde, summer pastures. Clinical signs are not often observed le diaphragme et la langue par exemple. Les lesions in affected calves due to the peracute nature of the macroscopiques primaires chez les animaux examines disease, but may include fever, lameness, and swelling etaient associees a des pleuresies et a des pericardites. and crepitation over large muscle groups, followed by Des lesions de charbon symptomatique plus typiques se collapse and death. Typical gross and histopathologic retrouvaient chez certains mais pas chez tous les veaux lesions in these muscle groups are well-described and atteints et incluaient une necrose dans les muscles de include gelatinous, gassy subcutaneous changes, along la cuisse et de l'abdomen, une decoloration foncee du with well-defined muscle necrosis. Areas of necrosis can muscle du diaphragme et des indices histologiques de also be present in myocardium, diaphragm, and tongue, myocardite necrotique. -

Clostridioides Difficileinfections

bioMérieux In vitro diagnostics serving CLOSTRIDIOIDES public health DIFFICILE INFECTIONS A major player in in vitro diagnostics for more than 50 years, From Diagnosis to bioMérieux has always been driven by a pioneering spirit and unrelenting commitment to improve public health worldwide. Outbreak Management Our diagnostic solutions bring high medical value to healthcare professionals, providing them with the most relevant and reliable information, as quickly as possible, to support treatment decisions and better patient care. bioMérieux’s mission entails a commitment to support medical education, by promoting access to diagnostic knowledge for as many people as possible. Focusing on the medical value of diagnostics, our collection of educational booklets aims to raise awareness of the essential role that diagnostic test results play in healthcare decisions. Other educational booklets are available. Consult your local bioMérieux representative. The information in this booklet is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be exhaustive. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a medical director, physician, or other qualified health provider regarding processes and/or protocols for diagnosis and treatment of a medical condition. bioMérieux assumes no responsibility or liability for any diagnosis established or treatment prescribed by the physician. bioMérieux, Inc. • 100 Rodolphe Street • Durham, NC 27712 • USA • Tel: (800) 682 2666 • Fax: (800) 968 9494 © 2019 bioMérieux, Inc. • BIOMERIEUX and the BIOMERIEUX logo, are used pending and/or registered trademarks belonging to bioMérieux, or one of its subsidiaries, or one of its companies. companies. its or one of subsidiaries, its or one of bioMérieux, belonging to trademarks registered pending and/or used are logo, and the BIOMERIEUX • BIOMERIEUX Inc. -

The Sialidase Nans Enhances Non-Tcsl Mediated Cytotoxicity of Clostridium Sordellii

toxins Article The Sialidase NanS Enhances Non-TcsL Mediated Cytotoxicity of Clostridium sordellii Milena M. Awad, Julie Singleton and Dena Lyras * Infection and Immunity Program, Biomedicine Discovery Institute and Department of Microbiology, Monash University, Clayton 3800, Australia; [email protected] (M.M.A.); [email protected] (J.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-3-9902-9155 Academic Editors: Harald Genth, Michel R. Popoff and Holger Barth Received: 24 March 2016; Accepted: 7 June 2016; Published: 17 June 2016 Abstract: The clostridia produce an arsenal of toxins to facilitate their survival within the host environment. TcsL is one of two major toxins produced by Clostridium sordellii, a human and animal pathogen, and is essential for disease pathogenesis of this bacterium. C. sordellii produces many other toxins, but the role that they play in disease is not known, although previous work has suggested that the sialidase enzyme NanS may be involved in the characteristic leukemoid reaction that occurs during severe disease. In this study we investigated the role of NanS in C. sordellii disease pathogenesis. We constructed a nanS mutant and showed that NanS is the only sialidase produced from C. sordellii strain ATCC9714 since sialidase activity could not be detected from the nanS mutant. Complementation with the wild-type gene restored sialidase production to the nanS mutant strain. Cytotoxicity assays using sialidase-enriched culture supernatants applied to gut (Caco2), vaginal (VK2), and cervical cell lines (End1/E6E7 and Ect1/E6E7) showed that NanS was not cytotoxic to these cells. However, the cytotoxic capacity of a toxin-enriched supernatant to the vaginal and cervical cell lines was substantially enhanced in the presence of NanS.