An Analysis of Js Bach's Partita in B Flat Major, Bwv 825; Wa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sarabande | Grove Music

Sarabande Richard Hudson and Meredith Ellis Little https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.24574 Published in print: 20 January 2001 Published online: 2001 Richard Hudson One of the most popular of Baroque instrumental dances and a standard movement, along with the allemande, courante and gigue, of the suite. It originated during the 16th century as a sung dance in Latin America and Spain. It came to Italy early in the 17th century as part of the repertory of the Spanish five- course guitar. During the first half of the century various instrumental types developed in France and Italy, at first based on harmonic schemes, later on characteristics of rhythm and tempo. A fast and a slow type finally emerged, the former preferred in Italy, England and Spain, the latter in France and Germany. The French spelling ‘sarabande’ was also used in Germany and sometimes in England; there, however, ‘saraband’ was often preferred. The Italian usage is ‘sarabanda’, the Spanish ‘zarabanda’. 1. Early development to c1640. The earliest literary references to the zarabanda come from Latin America, the name first appearing in a poem by Fernando Guzmán Mexía in a manuscript from Panama dated 1539, according to B.J. Gallardo (Ensayo de una biblioteca española de libros raros y curiosos, Madrid, 1888–9, iv, 1528). A zarabanda text by Pedro de Trejo was performed in 1569 in Mexico and Diego Durán mentioned the dance in his Historia de las Indias de Nueva-España (1579). The zarabanda was banned in Spain in 1583 for its extraordinary obscenity, but literary references to it continued throughout the early 17th century in the works of such writers as Cervantes and Lope de Vega. -

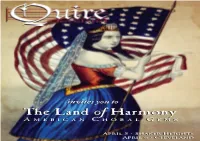

The Land of Harmony a M E R I C a N C H O R a L G E M S

invites you to The Land of Harmony A MERIC A N C HOR A L G EMS April 5 • Shaker Heights April 6 • Cleveland QClevelanduire Ross W. Duffin, Artistic Director The Land of Harmony American Choral Gems from the Bay Psalm Book to Amy Beach April 5, 2014 April 6, 2014 Christ Episcopal Church Historic St. Peter Church shaker heights cleveland 1 Star-spangled banner (1814) John Stafford Smith (1750–1836) arr. R. Duffin 2 Psalm 98 [SOLOISTS: 2, 3, 5] Thomas Ravenscroft (ca.1590–ca.1635) from the Bay Psalm Book, 1640 3 Psalm 23 [1, 4] John Playford (1623–1686) from the Bay Psalm Book, 9th ed. 1698 4 The Lord descended [1, 7] (psalm 18:9-10) (1761) James Lyon (1735–1794) 5 When Jesus wep’t the falling tear (1770) William Billings (1746–1800) 6 The dying Christian’s last farewell (1794) [4] William Billings 7 I am the rose of Sharon (1778) William Billings Solomon 2:1-8,10-11 8 Down steers the bass (1786) Daniel Read (1757–1836) 9 Modern Music (1781) William Billings 10 O look to Golgotha (1843) Lowell Mason (1792–1872) 11 Amazing Grace (1847) [2, 5] arr. William Walker (1809–1875) intermission 12 Flow gently, sweet Afton (1857) J. E. Spilman (1812–1896) arr. J. S. Warren 13 Come where my love lies dreaming (1855) Stephen Foster (1826–1864) 14 Hymn of Peace (1869) O. W. Holmes (1809–1894)/ Matthias Keller (1813–1875) 15 Minuet (1903) Patty Stair (1868–1926) 16 Through the house give glimmering light (1897) Amy Beach (1867–1944) 17 So sweet is she (1916) Patty Stair 18 The Witch (1898) Edward MacDowell (1860–1908) writing as Edgar Thorn 19 Don’t be weary, traveler (1920) [6] R. -

MUS 233 Form I Form: the Shape of a Musical Composition As Defined By

MUS 233 Form I Form: The shape of a musical composition as defined by all of its pitches, rhythms, dynamics, and timbres...a loose group of general features shared in varying degrees by a relatively large number of works, no two which are exactly the same. The New Harvard Dictionary of Music. Randel, Don Michael, ed. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1986. P. 320. Binary Form: A two part-form where the sections are equivalent, but not necessarily equal in length; as long as they balance each other in some sense. Each part usually repeats. The second half is longer and usually touches on other keys (X) before returning to the tonic. Balanced: In a binary form where the A and B sections end in a parallel (same melodic/harmonic material) way, but not necessarily in the same key. (Please disregard the Kostka/Payne definition, which relates the term to merely the length of each section). Sectional: The first part ends in tonic harmony (i.e. an authentic cadence on the original tonic). Thematic material ||: A :||: B :|| Harmonic content (maj) I-----------I V--------(X)-----------I (min) i-----------i V, V/III, III--(X)-----i Continuous: The first part ends in something other than tonic harmony (like on V, or on the tonic of a new key). Thematic material ||: A :||: B :|| Harmonic content (maj) I-----------V -----------(X)-----------I (min) i-----------V, V/III, III---(X)--------i Two reprise: A term used when the sections repeat (either written-out repeats or not). Ternary Form: A three-part (ABA’) form: ||:A :||: B A’ :|| (repeats not required) • A and A’ need not be 100% identical • Often the B section material is thematically related to the A section material. -

Gaspard Le Roux 1660-1707 Pièces De Clavessin (1705)

Gaspard Complete HarpsichordLe Roux Music Pieter-Jan Belder Siebe Henstra Gaspard le Roux 1660-1707 Pièces de Clavessin (1705) Suite in D minor/major Suite in F major 39. Sarabande (en douze couplets) 13’00 Pieter-Jan Belder harpsichord I 1. Prélude 0’46 21. Prélude 1’25 40. Menuet 1’01 (Solo on 16-26) 2. Allemande, “la Vauvert” 4’25 22. Allemande grave 3’05 41. Gigue (pour deux Clavecins) 1’52 Siebe Henstra harpsichord II 3. Courante 1’17 23. Courante 1’27 42. Courante (avec sa contre partie) 1’31 (Solo on harpsichord I, on 33-42 ) 4. Sarabande grave 2’05 24. Chaconne 4’03 5. Menuet 1’20 25. Menuet & 2 Doubles Suite in A minor/major Harpsichord I: Titus Crijnen after 6. Passepied 0’40 du Menuet 1’55 (solo version) Ruckers 1624, Sabiñan 2014 7. Courante luthée 1’55 26. Passepied 0’54 43. Prélude 0’50 Harpsichord II: Titus Crijnen after 8. Allemande grave, 27. Allemande 1’54 44. Allemande “l’Incomparable” 2’21 Blanchet 1731, Sabiñan 2013 “la Lorenzany” 3’28 45. Courante 1’29 9. Courante 1’28 Suite in F-sharp minor 46. Sarabande 2’02 10. Sarabande gaye 2’51 28. Allemande gaye 1’10 47. Sarabande en Rondeau 2’15 11. Gavotte 1’09 29. Courante 1’27 48. Gavotte 1’05 30. Double de la Courante 1’32 49. Menuet & double du Menuet 1’01 Suite in A minor/major 31. Sarabande grave en Rondeau 2’25 50. Second Menuet 0’32 12. Prélude 0’50 32. -

A Treatise on the Diseases Incident to the Horse

* ) . LIBRARY LINIVERSITYy^ PENNSYLVANIA j^ttrn/tause il^nriy GIFT OF FAIRMAN ROGERS Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/treatiseondiseasOOdunb (U^/^^c/^ i^^J-t^^-^t^^J-e^ A/ TREATISE ON THE ESPECIALLY TO THOSE OF THE FOOT, SHOWING THAT NEARLY EVERY SPECIES OF LAMENESS ARISES FROM CONTRACTION OF THE HOOF, WITH A PRESCRIBED REMEDY THEREFOR, DEMONSTRATED BY A MISCELLANEOUS CORRESPONDENCE OF THE MOST CELEBRATED HORSEMEN IN THE UNITED STATES AND ENGLAND, / ALEXANDER DUNBAR, ORIGINATOR OF THE CELEBRATED "DUNBAR SYSTEM" FOR THE PREVENTION AND CURE OF CONTRACTION. WILMINGTON, DEL. : JAMES & WEBB, PRINTERS AND PUBLISHERS, No, 224 Market Street. 187I. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1871, by Alkxanokb DcNBAR, in the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. 1 /1^ IftfDEX. .. PAGE. Introductory, ------- i CHAPTER I. Dunbar on the Horse, ------ g Instructions in Horse-Shoeing, - - - - - lo Testimonials in favor of Dunbar's system, - • - 1 " Lady Rysdyke" presented by Wm. M. Rysdyke, Esq., to Alexan- der Dunbar, - - - - - - - 15 Cut of Rysdyke's " Hambletonian," - - - - 17 Cut of portions of Hoof removed from "Old Hambletonian," - 17 CHAPTER n. Lady Rysdyke and Old Hambletonian, - - - - 19 CHAPTER HI. Testimonial of Robert Bonner in favor of the " Dunbar System," 25 How I obtained the knowledge of the "Dunbar" System, - 25 Letter of Hon. R. Stockett Matthews, - - - - 36 Letter of Lieut. General Grant, . ^6 First acquaintance with Messrs. Bruce, editors of "The Turf, Field and Farm," ------- 37 The Evils of Horse-Shoeing, or Difficulties of the Blacksmith, 38 Roberge's Patent Horse-Shoe, - - - - - 43 Dunbar's Objections to the "Rolling Motion Shoe," - - 44 CHAPTER IV. -

Allemande Johann Herrmann Schein Sheet Music

Allemande Johann Herrmann Schein Sheet Music Download allemande johann herrmann schein sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 1 pages partial preview of allemande johann herrmann schein sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 4280 times and last read at 2021-09-29 13:16:38. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of allemande johann herrmann schein you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Bassoon Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Beginning [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Canzon No 23 A Baroque Madrigal By Johann Hermann Schein For Brass Quintet Canzon No 23 A Baroque Madrigal By Johann Hermann Schein For Brass Quintet sheet music has been read 3565 times. Canzon no 23 a baroque madrigal by johann hermann schein for brass quintet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 17:32:11. [ Read More ] Allemande From The French Suite Number V By Johann Sebastian Bach Arranged For 3 Woodwinds Allemande From The French Suite Number V By Johann Sebastian Bach Arranged For 3 Woodwinds sheet music has been read 3664 times. Allemande from the french suite number v by johann sebastian bach arranged for 3 woodwinds arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-29 13:16:24. [ Read More ] Hinunter Ist Der Sonne Schein Fr Posaunenquartett Hinunter Ist Der Sonne Schein Fr Posaunenquartett sheet music has been read 3235 times. -

Harpsichord Suite in a Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet De La Guerre

Harpsichord Suite in A Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre Arranged for Solo Guitar by David Sewell A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved November 2019 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Frank Koonce, Chair Catalin Rotaru Kotoka Suzuki ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2019 ABSTRACT Transcriptions and arrangements of works originally written for other instruments have greatly expanded the guitar’s repertoire. This project focuses on a new arrangement of the Suite in A Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1665–1729), which originally was composed for harpsichord. The author chose this work because the repertoire for the guitar is critically lacking in examples of French Baroque harpsichord music and also of works by female composers. The suite includes an unmeasured harpsichord prelude––a genre that, to the author’s knowledge, has not been arranged for the modern six-string guitar. This project also contains a brief account of Jacquet de la Guerre’s life, discusses the genre of unmeasured harpsichord preludes, and provides an overview of compositional aspects of the suite. Furthermore, it includes the arrangement methodology, which shows the process of creating an idiomatic arrangement from harpsichord to solo guitar while trying to preserve the integrity of the original work. A summary of the changes in the current arrangement is presented in Appendix B. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my great appreciation to Professor Frank Koonce for his support and valuable advice during the development of this research, and also to the members of my committee, Professor Catalin Rotaru and Dr. -

A Conductor's Study of George Rochberg's Three Psalm Settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2002 A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, David, "A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings" (2002). LSU Major Papers. 51. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/51 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S STUDY OF GEORGE ROCHBERG’S THREE PSALM SETTINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in School of Music By David Alan Lawrence B.M.E., Abilene Christian University, 1987 M.M., University of Washington, 1994 August 2002 ©Copyright 2002 David Alan Lawrence All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................vi LIST -

Binary & Ternary Forms

Binary & Ternary Forms Formal Element Review • Motive: A motive is the smallest recognizable musical idea. o labeled with lowercase letters starting at the end of the alphabet • Phrase: a relatively independent musical idea that moves towards a cadence as its goal; a complete musical thought o labeled with lowercase letters starting at the beginning of the alphabet o subphrase: a musical unit smaller than a phrase but still a coherent gesture o sentence: a particular type of phrase or phrase group with an internal structure of 1+1+2 • Period: a pair of phrases that specifically work together in an antecedent-consequent relationship o First phrase (antecedent) will have an inconclusive cadence (half cadence or IAC) o Second phrase (consequent) will have a conclusive cadence (usually a PAC) Formal Structures • Formal structures are larger sections of music made up of these formal elements (phrases, periods, etc.) o typically labeled with uppercase letters starting at the beginning of the alphabet • Each standard formal structures contains a specific pattern of these larger sections (with minor variations) Factors to Consider in Formal Analysis • Key areas: in which key a phrase or section starts and/or ends o closed vs. open sections a closed section is self-contained - ends in the same key in which it begins with a conclusive cadence an open section is not self-contained - ends in a different key or with an inconclusive cadence - often features a half-cadence, modulation to the dominant, or modulation to the relative major • Motivic use: similar or contrasting motivic use within phrases or sections • Formal elements: phrases, cadences, periods, etc. -

Mozart's Piano

MOZART’S PIANO Program Notes by Charlotte Nediger J.C. BACH SYMPHONY IN G MINOR, OP. 6, NO. 6 Of Johann Sebastian Bach’s many children, four enjoyed substantial careers as musicians: Carl Philipp Emanuel and Wilhelm Friedemann, born in Weimar to Maria Barbara; and Johann Christoph Friedrich and Johann Christian, born some twenty years later in Leipzig to Anna Magdalena. The youngest son, Johann Christian, is often called “the London Bach.” He was by far the most travelled member of the Bach family. After his father’s death in 1750, the fifteen-year-old went to Berlin to live and study with his brother Emanuel. A fascination with Italian opera led him to Italy four years later. He held posts in various centres in Italy (even converting to Catholicism) before settling in London in 1762. There he enjoyed considerable success as an opera composer, but left a greater mark by organizing an enormously successful concert series with his compatriot Carl Friedrich Abel. Much of the music at these concerts, which included cantatas, symphonies, sonatas, and concertos, was written by Bach and Abel themselves. Johann Christian is regarded today as one of the chief masters of the galant style, writing music that is elegant and vivacious, but the rather dark and dramatic Symphony in G Minor, op. 6, no. 6 reveals a more passionate aspect of his work. J.C. Bach is often cited as the single most important external influence on Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart synthesized the wide range of music he encountered as a child, but the one influence that stands out is that of J.C. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

Akademie Für Alte Musik Berlin

UMS PRESENTS AKADEMIE FÜR ALTE MUSIK BERLIN Sunday Afternoon, April 13, 2014 at 4:00 Hill Auditorium • Ann Arbor 66th Performance of the 135th Annual Season 135th Annual Choral Union Series Photo: Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin; photographer: Kristof Fischer. 31 UMS PROGRAM Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C Major, BWV 1066 Ouverture Courante Gavotte I, II Forlane Menuett I, II Bourrée I, II Passepied I, II Johann Christian Bach (previously attributed to Wilhelm Friedmann Bach) Concerto for Harpsichord, Strings, and Basso Continuo in f minor Allegro di molto Andante Prestissimo Raphael Alpermann, Harpsichord Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach WINTER 2014 Symphony No. 5 for Strings and Basso Continuo in b minor, Wq. 182, H. 661 Allegretto Larghetto Presto INTERMISSION AKADEMIE FÜR ALTE MUSIK BERLIN AKADEMIE FÜR ALTE 32 BE PRESENT C.P.E. Bach Concerto for Oboe, Strings, and Basso Continuo in E-flat Major, Wq. 165, H. 468 Allegro Adagio ma non troppo Allegro ma non troppo Xenia Löeffler,Oboe J.C. Bach Symphony in g minor for Strings, Two Oboes, Two Horns, and Basso Continuo, Op. 6, No. 6 Allegro Andante più tosto adagio Allegro molto WINTER 2014 Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of floral art for this evening’s concert. Special thanks to Kipp Cortez for coordinating the pre-concert music on the Charles Baird Carillon. This tour is made possible by the generous support of the Goethe Institut and the Auswärtige Amt (Federal Foreign Office).