Harry S. Truman Trying to Make the Right Call

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universidade De Brasília Instituto De Relações Internacionais Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Relações Internacionais História Das Relações Internacionais

1 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE RELAÇÕES INTERNACIONAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM RELAÇÕES INTERNACIONAIS HISTÓRIA DAS RELAÇÕES INTERNACIONAIS LUIZ FERNANDO CASTELO BRANCO REBELLO HORTA TAMBORES DE GUERRA O REALISMO E O PODER DAS IDEIAS NO INÍCIO DA GUERRA FRIA (1945-1960) Brasília 2018 2 LUIZ FERNANDO CASTELO BRANCO REBELLO HORTA TAMBORES DE GUERRA O REALISMO E O PODER DAS IDEIAS NO INÍCIO DA GUERRA FRIA (1945-1960) Tese de Doutorado apresentada ao Instituto de Relações Internacionais da Universidade de Brasília, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Doutor em História das Relações Internacionais. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Estêvão de Rezende Martins Brasília 2018 3 LUIZ FERNANDO CASTELO BRANCO REBELLO HORTA TAMBORES DE GUERRA O REALISMO E O PODER DAS IDEIAS NO INÍCIO DA GUERRA FRIA (1945-1960) Tese de Doutorado defendida e aprovada como requisito parcial a obtenção do título de Doutor em História das Relações Internacionais pela banca examinadora constituída por: Aprovado em: _____ de _____ de _____. Banca Examinadora Orientador: Prof. Dr. Estêvão de Rezende Martins - IREL/UnB Prof.ª Dr. Geisa Cunha Franco - REL/UFG Prof. Dr. Aaron Schneider - Denver University/Josef Korbel School of International Studies Prof.ª Dr. Tânia Maria Pechir Gomes Manzur - IREL/UnB Prof. Dr. José Flávio Sombra Saraiva (Suplente) - IREL/UnB Brasília 2018 4 AGRADECIMENTOS Em primeiro lugar, agradeço, como não poderia ser diferente, à Gisele, quem divide comigo o tempo, as alegrias e dissabores dele. Especialmente nos últimos meses, quando minha ausência para a pesquisa a deixou só, só com as alegrias que fizemos juntos. E são três. Agradeço aos três pingos de gente que temos. -

'Harry Truman' by David Blanchflower

Harry Truman 12 April 1945 – 20 January 1953 Democrat By David Blanchflower Full name: Harry S Truman Date of birth: 8 May 1884 Place of birth: Lamar, Missouri Date of death: 26 December 1972 Site of grave: Harry S Truman Presidential Library & Museum, Independence, Missouri Education: Spalding’s Commercial College, Kansas City Married to: Bess Wallace. m. 1919. (1885-1982) Children: 1 d. Margaret "You know, it's easy for the Monday morning quarterback to say what the coach should have done, after the game is over. But when the decision is up before you - - and on my desk I have a motto which says The Buck Stops Here" Harry Truman, National War College, December 19th, 1952 'Give 'em hell' Harry S. Truman was the 33rd president of the United States and also the 33rd tallest. He was born on May 8th, 1884 and died at age 88 on December 22nd, 1972. Of note also is that V- E Day occurred on Truman's birthday on May 8th, 1945. He had no middle name. His parents gave him the middle initial, 'S', to honor his grandfathers, Anderson Shipp Truman and Solomon Young. He married his wife Elizabeth 'Bess' Wallace on June 28, 1919; he had previously proposed in 1911 and she turned him down; but they finally got engaged in 1913. She had been in his class at school when he was six and she was five, and she sat in the desk immediately behind him. The couple had one child, Mary Margaret Truman. Harry was a little man who did a lot, standing just 5 feet 9 inches tall which is short for a president. -

MLA Documentation and Works Cited Page

MLA: Works Cited Page This handout gives the most commonly used citations from the MLA Handbook, Eighth Edition. For more information, please refer to this handbook. If a portion of the information shown below does not exist for your source, omit it. For a template on how to cite any source in MLA format, consult page 129 of the MLA Handbook, Eighth Edition. Note: when you cite in MLA format, use a hanging indent (shown below). Books One author: Johnson, Roberta. Gender and Nation in the Spanish Modernist Novel. Vanderbilt UP, 2003. Two or more authors: Booth, Wayne C., Gregory G. Colomb, and Joseph M. Williams. The Craft of Research. 2nd ed., U of Chicago P, 2003. Two or more books by the same author (three hyphens indicate same author): Gilbert, Sandra M. Emily’s Bread. Norton, 1984. - - -. Ghost Volcano. Norton, 1995. An ORIGINAL Entry in an Anthology or Compilation: Hurston, Zora Neale. “Sweat.” The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Nellie Y. McKay, Norton, 1997, pp. 999-1007. A PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED Entry in an Anthology or Compilation (include date of original publication after the title of the piece): Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Fredrick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. 1845. Slave Narratives, edited by William L. Andrews and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Library of America, 2000, pp. 267- 368. Periodicals Magazine Article: Amelar, Sarah. “Restoration on 42nd Street.” Architecture, Mar. 1998, pp. 146-150. Newspaper Article: Boyar, Jay. “The Art of Bad Film Criticism.” Orlando Sentinel, 7 Jan. -

The BBC's Pardoner's Tale

A Popular Change from an Old Man to a Young Girl: The BBC’s Pardoner’s Tale (2003) Angus Cheng-yu Yen National Sun Yat-sen University, Taiwan Adaptation, as Julie Sanders defines it, is an attempt to invite new audiences and readers by re-presenting the source text in a simpler, more easily comprehensible manner. Among film adaptations of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, BBC’s 2003 reimagining provides unsurpassed sensitivity to modern issues, and a new relevance. Tony Ground narrates a modern tale intertwined with gothic elements and sex abuse scandals. Compared to the original text, BBC’s The Pardoner’s Tale leaves its reader not with the simple conclusion that avarice can be ultimately conquered, but with the complexities motivating a heinous crime. With the emphasis on the transformation of a character from a pallid old man to a florid young girl, this essay aims to discuss how the reframing of a medieval tale through popular culture sheds light on Chaucer’s reception and adaptation in the twenty-first century. Pasolini argued that it was impossible to make films about the past, idealized or otherwise, because the past had been irreparably corrupted by the present.1 ~Kevin J. Harty Everyone thinks they know the Canterbury Tales. Yet my experience of working on the Tales told me that no one can really remember much about them.2 ~Jonathan Myerson Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales have been adapted into numerous films, musicals, operas, and telefilms, including the BBC’s latest reproduction in 2003. Re- interpretation or re-production can either afford an alternative point of view from the 1 Kevin J. -

Primary Source Document with Questions (Dbqs) the POTSDAM DECLARATION (JULY 26, 1945) Introduction the Dropping of the Atomic Bo

Primary Source Document with Questions (DBQs) THE POTSDAM DECLARATION (JULY 26, 1945) Introduction The dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki remains among the most controversial events in modern history. Historians have actively debated whether the bombings were necessary, what effect they had on bringing the war in the Pacific to an expeditious end, and what other options were available to the United States. These very same questions were also contentious at the time, as American policymakers struggled with how to use a phenomenally powerful new technology and what the long-term impact of atomic weaponry might be, not just on the Japanese, but on domestic politics, America’s international relations, and the budding Cold War with the Soviet Union. In retrospect, it is clear that the reasons for dropping the atomic bombs on Japan, just like the later impact of nuclear technology on world politics, were complex and intertwined with a variety of issues that went far beyond the simple goal of bringing World War II to a rapid close. The Potsdam Declaration was issued on July 26, 1945 by U.S. President Harry Truman, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and President Chiang Kai-shek of the Republic of China, who were meeting in Potsdam, Germany to consider war strategy and post-war policy. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin also attended the Potsdam Conference but did not sign the Declaration, since the Soviet Union did not enter the war against Japan until August 8, 1945. Document Excerpts with Questions From Japan’s Decision to Surrender, by Robert J.C. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Timeline of the Cold War

Timeline of the Cold War 1945 Defeat of Germany and Japan February 4-11: Yalta Conference meeting of FDR, Churchill, Stalin - the 'Big Three' Soviet Union has control of Eastern Europe. The Cold War Begins May 8: VE Day - Victory in Europe. Germany surrenders to the Red Army in Berlin July: Potsdam Conference - Germany was officially partitioned into four zones of occupation. August 6: The United States drops atomic bomb on Hiroshima (20 kiloton bomb 'Little Boy' kills 80,000) August 8: Russia declares war on Japan August 9: The United States drops atomic bomb on Nagasaki (22 kiloton 'Fat Man' kills 70,000) August 14 : Japanese surrender End of World War II August 15: Emperor surrender broadcast - VJ Day 1946 February 9: Stalin hostile speech - communism & capitalism were incompatible March 5 : "Sinews of Peace" Iron Curtain Speech by Winston Churchill - "an "iron curtain" has descended on Europe" March 10: Truman demands Russia leave Iran July 1: Operation Crossroads with Test Able was the first public demonstration of America's atomic arsenal July 25: America's Test Baker - underwater explosion 1947 Containment March 12 : Truman Doctrine - Truman declares active role in Greek Civil War June : Marshall Plan is announced setting a precedent for helping countries combat poverty, disease and malnutrition September 2: Rio Pact - U.S. meet 19 Latin American countries and created a security zone around the hemisphere 1948 Containment February 25 : Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia March 2: Truman's Loyalty Program created to catch Cold War -

Greed and Grievance in Civil War

# Oxford University Press 2004 Oxford Economic Papers 56 (2004), 563–595 563 All rights reserved doi:10.1093/oep/gpf064 Greed and grievance in civil war By Paul Collier* and Anke Hoefflery *Centre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford yCentre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford, 21 Winchester Road, Oxford OX2 6NA; e-mail: anke.hoeffl[email protected] We investigate the causes of civil war, using a new data set of wars during 1960–99. Rebellion may be explained by atypically severe grievances, such as high inequality, a lack of political rights, or ethnic and religious divisions in society. Alternatively, it might be explained by atypical opportunities for building a rebel organization. While it is difficult to find proxies for grievances and opportunities, we find that political and social variables that are most obviously related to grievances have little explanatory power. By contrast, economic variables, which could proxy some griev- ances but are perhaps more obviously related to the viability of rebellion, provide considerably more explanatory power. 1. Introduction Civil war is now far more common than international conflict: all of the 15 major armed conflicts listed by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute for 2001 were internal (SIPRI, 2002). In this paper we develop an econometric model which predicts the outbreak of civil conflict. Analogous to the classic principles of murder detection, rebellion needs both motive and opportunity. The political science literature explains conflict in terms of motive: the circumstances in which people want to rebel are viewed as sufficiently rare to constitute the explanation. -

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008: the Role of Greed, Fear, and Oligarchs Cate Reavis

09-093 Rev. March 16, 2012 The Global Financial Crisis of 2008: The Role of Greed, Fear, and Oligarchs Cate Reavis Free enterprise is always the right answer. The problem with it is that it ignores the human element. It does not take into account the complexities of human behavior.1 – Andrew W. Lo, Professor of Finance, MIT Sloan School of Management; Director, MIT Laboratory of Financial Engineering The problem in the financial sector today is not that a given firm might have enough market share to influence prices; it is that one firm or a small set of interconnected firms, by failing, can bring down the economy.2 – Simon Johnson, Professor of Entrepreneurship, MIT Sloan School of Management; Former Chief Economist, International Monetary Fund On October 9, 2007, the Dow Jones Industrial Average set a record by closing at 14,047. One year later, the Dow was just above 8,000, after dropping 21% in the first nine days of October 2008. Major stock markets in other countries had plunged alongside the Dow. Credit markets were nearing paralysis. Companies began to lay off workers in droves and were forced to put off capital investments. Individual consumers were being denied loans for mortgages and college tuition. After the nine-day U.S. stock market plunge, the head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had some sobering words: “Intensifying solvency concerns about a number of the largest U.S.-based and European financial institutions have pushed the global financial system to the brink of systemic meltdown.”3 1 Interview with the case writer, April 10, 2009. -

Luck Be a Dreidl Tonight: "Millionaire," Chanukah and Other Games of Chance

Luck Be a Dreidl Tonight: "Millionaire," Chanukah and Other Games of Chance By Jennifer E. Krause People are talking about two new shows: ABC's "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?" and Fox's "Greed." "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?" and its host, Regis Philbin, burst on the television screen during the ratings dust bowl days of August, amidst re-runs and re-runs of re-runs. An estimated five million people responded to the show's call for contestants, and reportedly some 18 million people tuned in to witness the spectacle. Even now, amidst the stiff competition of November "sweeps," the fascination has not waned. The "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?" set is all neon and sweeping spotlights, and the music sounds eerily like the music you hear when newscasters are interrupting your regularly scheduled programming. The main attraction, of course, is that contestants can walk away with a million dollars in one night simply by answering a few questions. Before offering an answer, each person has to choose whether to go for broke or take the money and run. It is an alarmingly thrilling process to watch. I hesitate to say that I find myself sitting on the edge of my seat as "Reege" takes his sweet time revealing the right answer. I worry that Don from Tuscaloosa might lose his $64,000 jackpot trying to take a guess at the $125,000 question on "The Sound of Music." How many of those von Trapp kids were there? One wrong answer and you could lose it all, Don! What about your kids' college funds, that dream trip to Hawaii? The pressure mounts. -

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization the Origins of NATO the NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY ORGANIZATION

The Origins of N A TO THE NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY ORGANIZATION European Economic Recovery power production), and dollar reserves to pay for necessary and European Integration imports. The war had rent the social fabric of many nations, setting social class against social class and ethnic group n the aftermath of the total defeat of Nazi Germany in against ethnic group. Political tensions were exacerbated by 1945, Europe struggled to recover from the ravages of the participation of many Europeans in collaborationist occupation and war. The wartime Grand Alliance be- regimes and others in armed resistance. Masses of Europe- tweenI the Western democracies and the Soviet Union ans, radicalized by the experience of war and German collapsed, and postwar negotiations for a peace settlement occupation, demanded major social and economic change foundered in the Council of Foreign Ministers. By 1947 and appeared ready to enforce these demands with violence. peace treaties with Italy and the defeated Axis satellites were The national Communist Parties of Western Europe stood finally concluded after protracted and acrimonious negotia- ready to exploit this discontent in order to advance the aims tions between the former allies, but the problem of a divided of the Soviet Union.2 and occupied Germany remained unsettled. U.S. leaders were acutely aware of both the dangers of In April 1947 Secretary of State George Marshall re- renewed conflict in Europe and of their ability to influence turned from a frustrating round of negotiations in the the shape of a postwar European political and social order. Council of Foreign Ministers in Moscow to report that the Fresh from the wartime experience of providing major United States and the Soviet Union were at loggerheads over Lend-Lease aid to allied nations and assistance to millions of a prescription for the future of central Europe and that the refugees through the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Soviets appeared ready to drag out talks. -

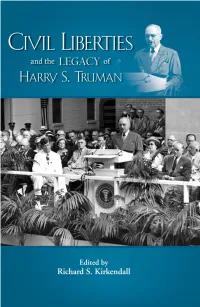

Civillibertieshstlookinside.Pdf

Civil Liberties and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman The Truman Legacy Series, Volume 9 Based on the Ninth Truman Legacy Symposium The Civil Liberties Legacy of Harry S. Truman May 2011 Key West, Florida Edited by Richard S. Kirkendall Civil Liberties and the LEGACY of Harry S. Truman Edited by Richard S. Kirkendall Volume 9 Truman State University Press Copyright © 2013 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover photo: President Truman delivers a speech on civil liberties to the American Legion, August 14, 1951 (Photo by Acme, copy in Truman Library collection, HSTL 76- 332). All reasonable attempts have been made to locate the copyright holder of the cover photo. If you believe you are the copyright holder of this photograph, please contact the publisher. Cover design: Teresa Wheeler Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Civil liberties and the legacy of Harry S. Truman / edited by Richard S. Kirkendall. pages cm. — (Truman legacy series ; 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61248-084-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-61248-085-5 (ebook) 1. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Political and social views. 2. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Influence. 3. Civil rights—United States—History—20th century. 4. United States. Constitution. 1st–10th Amendments. 5. Cold War—Political aspects—United States. 6. Anti-communist movements—United States— History—20th century. 7. United States—Politics and government—1945–1953. I. Kirkendall, Richard Stewart, 1928– E814.C53 2013 973.918092—dc23 2012039360 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher.