The University of Hull Korean Christianity and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just Unity: Toward a True Community of Women and Men in the Church

Just Unity: Toward a True Community of Women and Men in the Church Rachel Cosca Global Ecumenical Theological Institute HSST 2600 Christianity, Ecumenism and Mission in the 21st Century December 11, 2013 2 Despite the World Council of Church’s commendable and sometimes bold efforts to establish a just and true community of women and men in the church, the goal remains elusive. This is in part due to the pervasiveness of sexism in our world and the intractable nature of institutions, but it is also a consequence of some of the beliefs and traditions of the member churches. Given that the stated aim of the WCC is to “call one another to visible unity in one faith and one Eucharistic fellowship,”1 it must be questioned whether unity as it is currently conceived is compatible with gender justice. Prof. Dr. Atola Longkumer, in her lecture on Asian women, advocated a “posture of interrogation” toward structures, sources, and traditions that are oppressive or exclusive.2 In this vein, it is important to question whether unity is sometimes used as an alibi to maintain the status quo and silence voices on the periphery that may complicate the journey. We call for unity, but on whose terms? As the Ecumenical Conversation on Community of Women and Men in the Church at the Busan Assembly noted: “There is a tendency to compromise gender justice for ‘unity.’ Often this is expressed in the work of silencing and marginalizing women and/or gender justice perspectives.”3 Thus, this paper is intended to survey the ecumenical legacy of work for women’s full participation in church and society, engage Orthodox women’s voices in particular, probe the theological significance of unity, and look for signs of hope at the Busan Assembly. -

Notes Toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo

The Shrine : Notes toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo By A.W. S a d l e r Sarah Lawrence College When I arrived in Japan in the autumn of 1965, I settled my family into our home-away-from-home in a remote comer of Bunkyo-ku3 in Tokyo, and went to call upon an old timer,a man who had spent most of his adult life in Tokyo. I told him of my intention to carry out an exhaustive study of the annual festivals (taisai) of a typical neighbor hood shrine (jinja) in my area of residence,and I told him I had a full year at my disposal for the task. “Start on the grounds of the shrine/,was his solid advice; “go over every tsubo '(every square foot3 we might say),take note of every stone, investigate every marker.” And that is how I began. I worked with the shrines closest to home so that shrine and people would be part of my everyday life. When my wife and I went for an evening stroll, we invariably happened upon the grounds of one of our shrines; when we went to the market for fish or pencils or raaisnes we found ourselves visiting with the ujiko (parishioners; literally,children of the god of the shrine, who is guardian spirit of the neighborhood) of the shrine. I started with five shrines. I had great difficulty arranging for interviews with the priests of two of the five (the reasons for their reluc tance to visit with me will be discussed below) ; one was a little too large and famous for my purposes,and another was a little too far from home for really careful scrutiny. -

Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion

A (New) Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion Guillermo René Cavieses Araya Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Arts School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science February 2019 1 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Guillermo René Cavieses Araya The right of Guillermo René Cavieses Araya to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Guillermo René Cavieses Araya in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements No man is an island, and neither is his work. This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of a lot of people, going a long way back. So, let’s start at the beginning. Mum, thank you for teaching me that it was OK for me to dream of working for a circus when I was little, so long as I first went to University to get a degree on it. Dad, thanks for teaching me the value of books and a solid right hook. To my other Dad, thank you for teaching me the virtue of patience (yes, I know, I am still working on that one). -

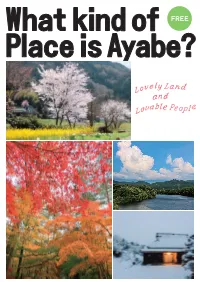

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

Modern Diffusion of Christianity in Japan: How Japanese View Christianity

3\1-1- MODERN DIFFUSION OF CHRISTIANITY IN JAPAN: HOW JAPANESE VIEW CHRISTIANITY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UINIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN COMMUNICATION AUGUST 2004 By Megumi Watanabe Thesis Committee: Jeffrey Ady, Chairperson Elizabeth Kunimoto George Tanabe © Copyright 2004 by Megumi Watanabe 111 Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my thesis committee chairperson, Dr. Jeffrey Ady, for his invaluable support and encouragement throughout the completion ofmy thesis. I would like to take this time to show my appreciation of my thesis committee members, Dr. Kunimoto and Dr. Tanabe, for their warm support and helpful comments. Also, my appreciation goes to Dr. Joung-Im Kim, who gave me valuable ideas and helped to develop my thesis proposal. My very special gratitude goes to my former advisor at Shizuoka University Dr. Hiroko Nishida, for giving me advice and assistance in obtaining the subjects. I would like to thank my friend Natsuko Kiyono who gave me helpful suggestions for my study, also Yukari Nagahara, Nozomi Ishii, Arisa Nagamura who helped collect data, and all my other friends who gave their time to participate in this proj ect. I would like to extend a special thanks to my friends Jenilee Kong, Gidget Agapito, Charity Rivera, and Miwa Yamazaki who generously shared their time to help me to complete this thesis, and provided me with profound advice. I would like to give a very special thanks to my parents and relatives for their extraordinary support and encouragement throughout my life and study in the United States. -

Christian Communication and Its Impact on Korean Society : Past, Present and Future Soon Nim Lee University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Christian communication and its impact on Korean society : past, present and future Soon Nim Lee University of Wollongong Lee, Soon Nim, Christian communication and its impact on Korean society : past, present and future, Doctor of Philosphy thesis, School of Journalism and Creative Writing - Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3051 This paper is posted at Research Online. Christian Communication and Its Impact on Korean Society: Past, Present and Future Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Wollongong Soon Nim Lee Faculty of Creative Arts School of Journalism & Creative writing October 2009 i CERTIFICATION I, Soon Nim, Lee, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Creative Arts and Writings (School of Journalism), University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Soon Nim, Lee 18 March 2009. i Table of Contents Certification i Table of Contents ii List of Tables vii Abstract viii Acknowledgements x Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Christianity awakens the sleeping Hangeul 12 Introduction 12 2.1 What is the Hangeul? 12 2.2 Praise of Hangeul by Christian missionaries -

Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Japanese Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Beate Fricke Summer 2018 © 2018 Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe All Rights Reserved Abstract Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature by Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair My dissertation investigates the role of images in shaping literary production in Japan from the 1880’s to the 1930’s as writers negotiated shifting relationships of text and image in the literary and visual arts. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), works of fiction were liberally illustrated with woodblock printed images, which, especially towards the mid-19th century, had become an essential component of most popular literature in Japan. With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868-1912), writers who had grown up reading illustrated fiction were exposed to foreign works of literature that largely eschewed the use of illustration as a medium for storytelling, in turn leading them to reevaluate the role of image in their own literary tradition. As authors endeavored to produce a purely text-based form of fiction, modeled in part on the European novel, they began to reject the inclusion of images in their own work. -

A Historical Overview of the Impact of the Reformation on East Asia Christina Han

Consensus Volume 38 Issue 1 Reformation: Then, Now, and Onward. Varied Article 4 Voices, Insightful Interpretations 11-25-2017 A Historical Overview of the Impact of the Reformation on East Asia Christina Han Follow this and additional works at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Korean Studies Commons, and the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Han, Christina (2017) "A Historical Overview of the Impact of the Reformation on East Asia," Consensus: Vol. 38 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus/vol38/iss1/4 This Articles is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Consensus by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Han: Reformation in East Asia A Historical Overview of the Impact of the Reformation on East Asia Christina Han1 The Reformation 500 Jubilee and the Shadow of the Past he celebratory mood is high throughout the world as we approach the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. Themed festivals and tours, special services and T conferences have been organized to commemorate Martin Luther and his legacy. The jubilee Luther 2017, planned and sponsored the federal and municipal governments of Germany and participated by churches and communities in Germany and beyond, lays out the goals of the events as follows: While celebrations in earlier centuries were kept national and confessional, the upcoming anniversary of the Revolution ought to be shaped by openness, freedom and ecumenism. -

Nskk Newsletter 日本聖公会管区事務所だより

Vol.XXVI #1 December 2014 NSKK NEWSLETTER 日本聖公会管区事務所だより NIPPON SEI KO KAI Provincial Office Editor : Egidio Hajime Suzuki 65 Yarai-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tel. +81-3-5228-3171 Tokyo 162-0805 JAPAN Fax +81-3-5228-3175 The Resolution of General Synod, 2014 – Issues Facing NSKK – The Most Rev. Nathaniel Makoto Uematsu Primate and Chairperson of the General Synod The 61st (Regular) General Synod of the Nippon Sei Ko Kai(NSKK) was held from 27th to 29th May 2014 at Ushigome Sei Ko Kai, St. Barnabas’ Church in the Tokyo Diocese. In the opening speech of the General Synod, I recollected the last two-year period of the General Synod, and took up some important points which the NSKK has confronted. I have made a review of our current activities as well as our standpoints. In the following, I am going to mention several resolutions which were considered during the present General Synod. (1) Three years and two months have passed since the Great East Japan Earthquake. The NSKK’s “Let’s Walk Together!” project finished its original two-year working period last May (in August in the Kamaishi Area). This means that the original activities have been more or less completed. The present General Synod was the first one held after completion of the project, at which many relevant reports were presented and the whole results were reassessed. I must mention that during the period since the earthquake, the NSKK has “walked together” with the victims, praying, supporting or working in union with them. This is an event that deserves special mention in the history of the NSKK. -

The Enneagram and Its Implications

Organizational Perspectives on Stained Glass Ceilings for Female Bishops in the Anglican Communion: A Case Study of the Church of England Judy Rois University of Toronto and the Anglican Foundation of Canada Daphne Rixon Saint Mary’s University Alex Faseruk Memorial University of Newfoundland The purpose of this study is to document how glass ceilings, known in an ecclesiastical setting as stained glass ceilings, are being encountered by female clergy within the Anglican Communion. The study applies the stained glass ceiling approach developed by Cotter et al. (2001) to examine the organizational structures and ordination practices in not only the Anglican Communion but various other Christian denominations. The study provides an in depth examination of the history of female ordination within the Church of England through the application of managerial paradigms as the focal point of this research. INTRODUCTION In the article, “Women Bishops: Enough Waiting,” from the October 19, 2012 edition of Church Times, the Most Rev. Dr. Rowan Williams, then Archbishop of Canterbury, urged the Church of England in its upcoming General Synod scheduled for November 2012 to support legislation that would allow the English Church to ordain women as bishops (Williams, 2012). Williams had been concerned about the Church of England’s inability to pass resolutions that would allow these ordinations. As the spiritual head of the Anglican Communion of approximately 77 million people worldwide, Williams had witnessed the ordination of women to the sacred offices of bishop, priest and deacon in many parts of the communion. Ordinations allowed women in the church to overcome glass ceilings in certain ministries, but also led to controversy and divisiveness in other parts of the church, although the Anglican Communion has expended significant resources in both monetary terms and opportunity costs to deal with the ordination of women to sacred offices, specifically as female bishops.