Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

LCD-80-24 Realignment of the Cleveland Defense Contract

.... S~UNITED STATES GENERAL ACCOUNTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D.C. 20548 LOGISTICS AND COMMUNICATIONS DIVISION DIVONII IIW NOVEMBER 29,1979 B-168700 110978 Cl6 The Honorable John Glenn, United States Senate The Honorable Ronald M. Mottl, House of Representatives The Honorable Mary Rose Oakar, House of Representatives The Honorable Louis Stokes, House of Representatives The Honorable Charles A. Vanik, House of Representatives Subject:ERealinement of the Cleveland Defense Contract Administration Service Region](LCD-80-24) You requested that we review the Defense Logistics Agency's decision to merge the Defense Contract Administra- /- tion Service's Cleveland regional office into the Chicago -/regional office. Recent events have eliminated Chicago as a potential location, and as Admiral E. M. Kocher, Assistant Director, Defense Logistics Agency, advised you in his October 16, 1979, letter, the Agency has now decided to locate the consolidated office in Cleveland. The merger of these two offices is part of an overall Department of Defense plan. By reducing the number of Defense Contract Administration Service's regions from nine to five, Defense will reduce overhead and administrative costs and attain a more efficient support structure. The Agency pro- jected that this consolidation could save about $40 million over 5 years, about $18 million attributable to the Cleveland- Chicago consolidation. The Agency also projected that if the consolidated office was located in Chicago, about $1 million more could be saved. On October 11, 1979, our review team provided a briefing on the progress of our work. Our preliminary analysis showed that Chicago was economically more advantageous than Cleveland. However, the estimates and projections contained so many judg- ments and assumptions that a decision could not be based unequivocally on economic factors. -

U.S. ELECTION ASSISTANCE COMMISSION 2020 Annual Report

U.S. ELECTION ASSISTANCE COMMISSION 2020 Annual Report GCC ZOOM CONGRESSINAL HEARING TYEuL EEC T IONS CEYcBuERRITY s1GNATURE ~~~LJs SEC U RI 5 VERIFICATION NEW HIRES VOTERS CONTINGENCY RUTGERS EARLY BALLOT GUIDANCE CTCL 2 0 0 INNOVA!J~EPLANNING 0IsINF0RMATI0N~¼~~i1~~T~a.~. - DEM1~r~ 8 ~ s EXECUTIVE i:2 w<( ASSISTANCEACC Es s I B I LI TY CIS FEEDBACK c~~~~l~:1~~0CRITICAL 400 M TESTING AND COVI D wow INF RASTR uCTU RE NATIONAL POLL WORKER RECRUITMENT DAY GRANTS KEY CERTIFICATION 80 WORKING~ GUIDELINES SECRETARY COVI D-19Aot1RSDOORSF ~iNt&R voi E~REt~rA~l~¼LABS GROUPR~~fJRB MAIL~!ti~:;~:: IT BACK2Q20 OF STATE ELECTIONRECOUNTSoELA~~t9vN OUTREACH REGISTRATION , 1 MOVE ACCURATE CARES GRANTZ POLL NVRD EAC ~~!i~~~ STATE AND LOCALPPE l~Fit{;f~~ ~~~ERSARY OF WOMEN VOTERS ~ WORKERS EAVS MASKS EL~~~~?~L~>ft~~~~~ ~~MA E-BALL0T SAFEGUARD PANDEMIC <! VOTING IN PERSO~~VOTER EDUCATIONREOUIREMENTS DELIVERY VOTING BY S0 LARWINDS c::::: - N BALLOTS SITUATION ROOM HEARINGS MAIL VOTING MACHINES 02 VOTE R PANDEMIC BEST RESOURCES 1 PHISHING CLEARINGHOUSE O R E SPONSE t~1~T~~8ii ~~T DISBURSEMENT RISK LL ELECTION NIGHT REPORTING MAIL MANA GEMt ~N~ RN r ~~J~ti;.NCENPWRD ~ ~ ~ ~c::::: Tu u LESSONS LEARNED w a:: ~ ..::::; O RESOURCES u.~ ~ NEWSLETTERWEBINARS PATCHING SECURE sec HEALTH 1 SAFE ~~~ C~UD ~00 Dill SERVICES STANDARDS HAVA BOARD MANUFACTURERS NIST TGDC BMDs Serving America•s Election Officials and Voters During the COVID-19 Pandemic 2020 EAC Annual Report: Serving America’s Election Officials and Voters Table of Contents Chairman’s Message 4 Meet the Commissioners 6 Executive Director’s Letter 11 General Counsel’s Update 14 Executive Summary 15 Administering HAVA Funds 24 Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic 28 The 2020 Election: Assisting Election Officials and Voters 35 Enhancing Election Security 46 Setting New National Standards for Voting Systems 48 Leveraging Data 52 Promoting Accessibility 55 Highlighting Best Practices 59 EAC Agency Development 61 EAC Advisory & Oversight Boards 65 Appendix 78 4 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE When the year began, the U.S. -

Ohio Senate Journal

JOURNALS OF THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OHIO SENATE JOURNAL TUESDAY, JANUARY 11, 2011 22 SENATE JOURNAL, TUESDAY, JANUARY 11, 2011 FIFTH DAY Senate Chamber, Columbus, Ohio Tuesday, January 11, 2011, 1:30 p.m. The Senate met pursuant to adjournment. Prayer was offered by Father Michael Lumpe, St. Catharine's Church, Bexley, Ohio, followed by the Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag. The journal of the last legislative day was read and approved. On the motion of Senator Faber the Senate advanced to the ninth Order of Business, Offering of Resolutions. OFFERING OF RESOLUTIONS Senator Faber offered the following resolution: S. R. No. 4-Senator Faber. Relative to the appointment of Peggy B. Lehner, to fill the vacancy in the membership of the Senate created by the resignation of Jon Husted of the 6th Senatorial District. WHEREAS, Section 11 of Article II, Ohio Constitution, provides for the filling of a vacancy in the Senate by appointment by the members of the Senate who are affiliated with the same political party as the person last elected to the seat which has become vacant; and WHEREAS, Jon Husted of the 6th Senatorial District has resigned as a member of the Senate effective January 9, 2011, thus creating a vacancy in the Senate; now therefore be it RESOLVED, By the members of the Senate who are affiliated with the Republican party, that Peggy B. Lehner (Republican), having the qualifications set forth in the Ohio Constitution and the laws of Ohio to be a member of the Senate from the 6th Senatorial District is hereby appointed, pursuant to Section 11 of Article II, Ohio Constitution, as a member of the Senate from the 6th Senatorial District, to fill the vacancy created by Jon Husted; and be it further RESOLVED, That a copy of this Resolution be spread upon the journal of the Senate together with the yeas and nays of the members of the Senate affiliated with the Republican party voting on the Resolution, and that the Clerk of the Senate shall certify the Resolution and the vote on its adoption to the Secretary of State. -

Xavier Becerra 1958–

H CURRENT HISPANIC-AMERICAN MEMBERS H Xavier Becerra 1958– UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 1993– DEMOCRAT FROM CALIFORNIA Xavier Becerra had barely completed one term in the California state assembly when he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1992. During his career in Washington, Becerra has emerged as a Democratic leader, becoming the first Latino in the history of the House to sit on the powerful Ways and Means Committee and being elected twice by his colleagues to serve as the Image courtesy of the Member Vice Chairman of the House Democratic Caucus. Xavier Becerra was born in Sacramento, California, on January 26, 1958, the third of four children to working-class parents Maria Teresa and Manuel Becerra. He majored in economics and graduated in 1980 from Stanford University, near Palo Alto, California, becoming the first member of his family to earn a bachelor’s degree.1 He stayed on at Stanford, earning a law degree in 1984, before working as an aide to a California state senator and then becoming a California deputy attorney general. After Becerra moved to Los Angeles, community leaders encouraged him to run for the state assembly in 1990.2 Becerra was young and relatively unknown, and his victory that year galvanized a new generation of Latino politicians.3 Before the expiration of Becerra’s first term in the state assembly, venerable Los Angeles Democrat Edward R. Roybal retired from the U.S. House. California had just redrawn its congressional districts, shifting the border of Roybal’s 30th District westward from East Los Angeles to Hollywood. -

Election Notice for Use with the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (FWAB) R.C

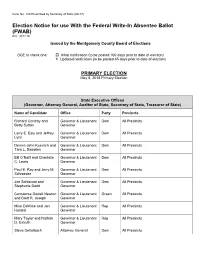

Form No. 120 Prescribed by Secretary of State (09-17) Election Notice for use With the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (FWAB) R.C. 3511.16 Issued by the Montgomery County Board of Elections BOE to check one: Initial notification (to be posted 100 days prior to date of election) X Updated notification (to be posted 45 days prior to date of election) PRIMARY ELECTION May 8, 2018 Primary Election State Executive Offices (Governor, Attorney General, Auditor of State, Secretary of State, Treasurer of State) Name of Candidate Office Party Precincts Richard Cordray and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Betty Sutton Governor Larry E. Ealy and Jeffrey Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Lynn Governor Dennis John Kucinich and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Tara L. Samples Governor Bill O’Neill and Chantelle Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts C. Lewis Governor Paul E. Ray and Jerry M. Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Schroeder Governor Joe Schiavoni and Governor & Lieutenant Dem All Precincts Stephanie Dodd Governor Constance Gadell-Newton Governor & Lieutenant Green All Precincts and Brett R. Joseph Governor Mike DeWine and Jon Governor & Lieutenant Rep All Precincts Husted Governor Mary Taylor and Nathan Governor & Lieutenant Rep All Precincts D. Estruth Governor Steve Dettelbach Attorney General Dem All Precincts Dave Yost Attorney General Rep All Precincts Zack Space Auditor of State Dem All Precincts Keith Faber Auditor of State Rep All Precincts Kathleen Clyde Secretary of State Dem All Precincts Frank LaRose Secretary of State Rep All Precincts Rob Richardson Treasurer of State Dem All Precincts Sandra O’Brien Treasurer of State Rep All Precincts Robert Sprague Treasurer of State Rep All Precincts Paul Curry (Write-In) Treasurer of State Green All Precincts U.S. -

MEETING ROSTER Brain Injury

MEETING ROSTER Brain Injury Rehabilitation Research and Development Parent IRG Office of Research & Development RRDB Agenda Seq Num - 254822 August 14, 2012 - August 15, 2012 CHAIRPERSON HIGH, WALTER MORRIS JR, PHD * ABRAMS, GARY MITCHELL, MD NEUROPSYCHOLOGIST/ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR REHABILITATION SECTION CHIEF/PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS LEXINGTON KENTUCKY VAMC SAN FRANCISCO VAMC NEUROLOGY SERVICE PHYSCIAL MEDICINE AND REHABILITATION SERVICES UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF LEXINGTON, KY 40504 NEUROLOGY SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94121 JAFFEE, MICHAEL S., MD * NATIONAL DIRECTOR MEMBERS DEFENSE AND VETERANS BRAIN INJURY CENTER BAKER, DEWLEEN GAY, MD * FOR PSYCHOLOGICAL HEALTH & TRAUMATIC BRAIN STAFF PHYSICIAN/ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR LACKLAND AIRFORCE BASE VA SAN DIEGO HEALTHCARE SYSTEM SAN ANTONIO, TX 78228 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO KLINE, ANTHONY E, PHD * SAN DIEGO, CA 92161 ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR BRENNER, LISA A. PHD * PHYSICAL MEDICINE & REHABILITATION UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIRECTOR DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS PITTSBURGH, PA 15213 EC HEALTHCARE SYSTEM KUHN, DONALD M, PHD * VA VISN 19 MIRECC PROFESSOR DENVER, CO 80220 DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHIATRY CHAPMAN, JULIE CATHERINE * AND BEHAVIORAL NEUROSCIENCES NEUROSCIENTIST SCHOOL OF MEDICINE VETERANS AFFAIRS MEDICAL CENTER WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY 50 IRVING STREET DETROIT, MI 48201 WASHINGTON, DC 20422 MCKEE, ANN CAROLYN MD, MD * CHOI, LEENA, PHD * ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR NEUROLOGY & PATHOLOGY ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT -

Joe Crowley (D-Ny-14)

LEGISLATOR US Representative JOE CROWLEY (D-NY-14) IN OFFICE CONTACT Up for re-election in 2016 Email Contact Form LEADERSHIP POSITION https://crowley.house.gov/ contact-me/email-me House Democratic Caucus Web crowley.house.gov 9th Term http://crowley.house.gov Re-elected in 2014 Twitter @repjoecrowley https://twitter.com/ repjoecrowley Facebook View on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/ repjoecrowley DC Office 1436 Longworth House Office Building BGOV BIOGRAPHY By Brian Nutting and Mina Kawai, Bloomberg News Joseph Crowley, vice chairman of the Democratic Caucus for the 113th Congress and one of the party's top campaign money raisers, works for government actions that benefit his mostly middle-class district while keeping in mind the needs of Wall Street financial firms that employ many of his constituents. He has served on the Ways and Means Committee since 2007. He was a key Democratic supporter of the 2008 bailout of the financial services industry -- loudly berating Republicans on the House floor as an initial bailout bill went down to defeat -- as well as subsequent help for the automobile industry. In addition to his post as caucus vice chairman -- the fifth-ranking post in the Democratic leadership -- Crowley is also a finance chairman for the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, the political arm of House Democrats, and serves on the Steering and Policy Committee. He has a garrulous personality to match his burly, 6-foot-4 frame. He's been known to break into song and is generally well-liked by friend and foe alike. Crowley has been a solid supporter of Democratic Party positions, as illustrated by the ratings he has received from organizations on opposite ends of the political spectrum: A lifetime score of 90 percent-plus from the liberal Americans for Democratic Action and 8 percent, through 2012, from the American Conservative Union He favors abortion rights, gun control and same-sex marriage. -

Donor Report 2007

OUR LAND. OUR LEGACY. OUR LAND. OUR LEGACY. P.O. Box 314 · Novelty, Ohio 44072 • Phone: 440-729-9621 • Fax: 440-729-9631 e-mail: [email protected] • www.wrlc.cc FIELD OFFICES: Akron Field Offi ce 34 Merz Boulevard, Suite G, Akron, Ohio 44333 • Phone: 330-836-2271 • Fax: 330-836-2272 Medina Field Offi ce 141 Prospect Street, Medina, Ohio 44258 • Phone: 330-722-7313 • Fax: 330-722-6592 Firelands Field Offi ce P.O. Box 174, Oberlin, Ohio 44074 • Phone: 440-774-4226 • Fax: 440-774-6409 OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES STAFF James C. Spira Ned Baker Dennis Bower Chair Dick Brubaker Eddie Dengg Owen M. Colligan Jean Gokorsch Julia S. Bolton Evan R. Corns Scott Hill Vice Chair C. Beau Daane Janet Hoover Stanley L. Fischer Dawn Hummer Richard S. Grimm James Gerspacher Bill Jordan Vice Chair Robert N. Gudbranson Carla Macklin David Halstead Pete McDonald J. Jeffrey Holland Rick Hawksley Andy McDowell Vice Chair Elizabeth Juliano Ed Meyers Kathy Keare Leavenworth Anne Murphy Sandra Pickut McMannis John D. Leech Julia Musson Vice Chair James R. Levine Katie Outcalt Kathryn L. Makley Bob Owen William C. Mulligan S. Sterling McMillan, IV Gina Pausch Marion Olson Vice Chair Kate Pilacky Gordon Oney Mark Skowronski Todd R. Ray Richard C. Hyde Amy Terpay Franz Sauerland Treasurer Kim Van Sickler Thomas J. Schultz Leah Whidden Michael R. Shaughnessy James G. Watterson Donna L. Studniarz Secretary Grant M. Thompson “The world was not left to us by our parents. Tracy Wallach Edward F. Meyers Norman Webb It was lent to us by our children.” Assistant Secretary Richard D. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States BRIEF for the STATES OF

No. 09-559 In the Supreme Court of the United States _________________________________ JOHN DOE #1, JOHN DOE #2, AND PROTECT MARRIAGE WASHINGTON, Petitioners, v. SAM REED, WASHINGTON SECRETARY OF STATE, AND BRENDA GALARZA, PUBLIC RECORDS OFFICER FOR THE SECRETARY OF STATE’S OFFICE, Respondents. _________________________________ ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT _________________________________ BRIEF FOR THE STATES OF OHIO, ARIZONA, COLORADO, FLORIDA, IDAHO, ILLINOIS, MAINE, MARYLAND, MASSACHUSETTS, MISSISSIPPI, MONTANA, NEW HAMPSHIRE, NEW JERSEY, NEW MEXICO, NORTH DAKOTA, OKLAHOMA, OREGON, SOUTH CAROLINA, SOUTH DAKOTA, TENNESSEE, UTAH, VERMONT, AND WISCONSIN AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS ___________________________________ BENJAMIN C. MIZER* RICHARD CORDRAY Solicitor General Attorney General of Ohio *Counsel of Record 30 E. Broad St., 17th Floor ELISABETH A. LONG Columbus, Ohio 43215 Deputy Solicitor 614-466-8980 SAMUEL PETERSON benjamin.mizer@ Assistant Solicitor General ohioattorneygeneral.gov Terry Goddard Janet T. Mills Attorney General Attorney General State of Arizona State of Maine 1275 West Washington 6 State House Station Phoenix, AZ 85007 Augusta, ME 04333 John W. Suthers Douglas F. Gansler Attorney General Attorney General State of Colorado State of Maryland 1525 Sherman St. 200 Saint Paul Place Seventh Floor Baltimore, MD 21202 Denver, CO 80203 Martha Coakley Bill McCollum Attorney General Attorney General State of Massachusetts State of Florida One Ashburton Place The Capitol, PL-01 Boston, MA 02108 Tallahassee, FL 32399 Jim Hood Lawrence G. Wasden Attorney General Attorney General State of Mississippi State of Idaho Post Office Box 220 P.O. Box 83720 Jackson, MS 39205 Boise, ID 83720 Steve Bullock Lisa Madigan Attorney General Attorney General State of Montana State of Illinois P.O. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE April 21, 1999

April 21, 1999 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE 7081 work on cleaning up our rivers. He to show some blue collar voters that he a nonpartisan primary and he was de- stood with us when we blocked efforts was proficient in the use of a blow feated by two other individuals. One that would have prohibited EPA from torch, accidentally set his hair on fire. was a Member who served in this doing more to clean up the air that we But Clevelanders love to tell the House, Ed Feighan, and the other is my all breathe. story about when Mayor Perk, a Re- very distinguished greater Clevelander, He stood with us on protecting chil- publican, was invited to a State dinner the gentleman from Ohio (Mr. DENNIS dren’s health from asthma caused by by then President Richard Nixon, and KUCINICH), who then went on to serve airborne pollution, illness caused by it conflicted with his wife Lucy’s bowl- as mayor of Cleveland, and now serves food poisoning, and pesticide poisoning, ing night, so he was not able to be in with us in the House. permanent damage caused by toxic attendance on that particular evening. I yield to my friend, the gentleman wastes let loose in the environment. Mr. Speaker, Ralph Perk was vintage from Ohio (Mr. KUCINICH) for his The Vice President stood with us on all Cleveland, and he will be greatly thoughts and remembrances of Mayor those issues. missed. He is best known as Cleveland’s Perk. The American people want clean air mayor, but he had a distinguished ca- Mr. -

R. Bruce Josten Executive Vice President, Government Affairs U.S

U.S. Chamber of Commerce Association Committee of 100 June 23, 2014 The Greenbrier White Sulphur Springs, WV Remarks by: R. Bruce Josten Executive Vice President, Government Affairs U.S. Chamber of Commerce Last fall, I suggested to this group that the government was simply not working and that doubts about the government’s ability to function were growing. In January the NYTs reported on an AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll that found Americans “with a profoundly negative view of their government with 70% lacking confidence in the government's ability “to make progress on the important problems and issues facing the country in 2014.” While that poll no doubt reflected the government shutdown, the same poll found Americans divided on how active they want government to be. Half said "the less government the better." Yet, almost as many (48 percent) said "there are more things that government should be doing." Pew released a poll that found for the first time in polling, a majority of the public (53%) believes their federal government threatens their personal rights and freedoms. That finding was followed by a Gallup poll reporting a record-high 72% of Americans naming “big government” as the greatest threat to the country in the future. A USA Today/Bipartisan Policy Center poll found no partisan divide with Americans saying it’s more important for Congress to stop bad laws than to pass new laws with 54% of Republicans and 51% of Democrats agreeing. Polls, however, continue to show that at the core of American’s frustration and alienation is the belief today that the American Dream is no longer attainable.