Introduction to the Special Issue Civil Society in Ukraine: Building on Euromaidan Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASD-Covert-Foreign-Money.Pdf

overt C Foreign Covert Money Financial loopholes exploited by AUGUST 2020 authoritarians to fund political interference in democracies AUTHORS: Josh Rudolph and Thomas Morley © 2020 The Alliance for Securing Democracy Please direct inquiries to The Alliance for Securing Democracy at The German Marshall Fund of the United States 1700 18th Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 683 2650 E [email protected] This publication can be downloaded for free at https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/covert-foreign-money/. The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the authors alone. Cover and map design: Kenny Nguyen Formatting design: Rachael Worthington Alliance for Securing Democracy The Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD), a bipartisan initiative housed at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, develops comprehensive strategies to deter, defend against, and raise the costs on authoritarian efforts to undermine and interfere in democratic institutions. ASD brings together experts on disinformation, malign finance, emerging technologies, elections integrity, economic coercion, and cybersecurity, as well as regional experts, to collaborate across traditional stovepipes and develop cross-cutting frame- works. Authors Josh Rudolph Fellow for Malign Finance Thomas Morley Research Assistant Contents Executive Summary �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Introduction and Methodology �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

The Features of Ukrainian Media Art in a Global Context

IJCSNS International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security, VOL.21 No.4, April 2021 229 The Features of Ukrainian Media Art in a Global Context Tamara O. Hridyayeva 1†, Volodymyr A. Kohut 1††, Maryna I. Tokar2†††, Oleg O. Stanychnov2†††† and Andrii A. Helytovych3††††† 1Lviv National Academy of Arts, Lviv, Ukraine 2Kharkiv State Academy of Design and Arts, Kharkiv, Ukraine 3 Art School n.a. O. Novakivskyi, Lviv, Ukraine Summary In the context of the growing complexity and The article seeks to explore Ukrainian media art and its features in conflictogenity of media, the self-actualization of art and a global context. In particular, it performs an in-depth analysis of creativity of both an individual artist and an individual the stages of its development from video art of the 1990s, media national art is a certain existential challenge. Modern media installations of the 2000s, and to various digital and VR culture is a space in which numerous innovative technologies today. Due to historical circumstances, the experiences rapidly emerge and new opportunities for development of media art was quite rapid, as young artists sought to gain new experience in media art. Most often, their experience creativity and advanced levels of knowledge arise. was broadened through international cooperation and studying Accordingly, considering Ukrainian media art in the context abroad. The paper analyzes the presentation of Ukrainian media of its presentation on the world art platform, it seems art outside the country during 1993-2020 and distinguishes the relevant to discuss to what extent it aligns with the global main thematic areas of the artists’ work. -

Festival D'in(Ter)Vention Z, Audio — Performance — Vidéo — Radio Art Interzone Uébec

Document generated on 09/29/2021 6:28 a.m. Inter Art actuel Interzone Festival d’in(ter)vention 7 Number 55-56, Fall 1992, Winter 1993 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1098ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Les Éditions Intervention Explore this journal Cite this document (1992). Interzone : festival d’in(ter)vention 7. Inter, (55-56), 105–140. Tous droits réservés © Les Éditions Intervention, 1993 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ FESTIVAL D'IN(TER)VENTION Z, AUDIO — PERFORMANCE — VIDÉO — RADIO ART INTERZONE UÉBEC EDITE U R INTERZONE Festival d'ln(ter)vention 7 INTERZONE 20 au 25 octobre 1992, Québec Production : Nathalie PERREAULT, Richard MARTEL LES ARTISTES : ALGOJO) (ALGOJO : Éric LÉTOURNEAU, Martine H. CRISPO (Québec), Collaboration : Pierre-André ARCAND (Québec), Anna BANANA (Canada), Guy DURAND, Claire GRAVEL, TimBRENNAN (Angleterre), Eugene CHADBOURNE (États-Unis), Richard MARTEL, Yvan PAGEAU, DOYON/DEMERS (Québec), Bartoloméo FERRANDO (Espagne), Sonia PELLETIER, Clive ROBERTSON, Giovanni FONTANA (Italie), Jean-Yves FRECHETTE (Québec), les artistes. Louis HACHÉ (Québec), Kirsteen JUSTESEN (Danemark), Itsvan KANTOR Monty CANTSIN AMEN (Québec), Correction et révision : Cécile BOUCHARD Benoît LACHAMBRE (Québec), Sandra LOCKWOOD (Canada), Alastair MacLENNAN (Irlande), Sandy McFADDEN (Canada), Correction de l'anglais : Otto MESZAROS (Tchécoslovaquie), Jerzy ONUCH (Canada), Mono DESGAGNÉ Ahasiw K. -

The Promotion of Art and Culture in Central Eastern Europe 1St CEI

The Promotion of Art and Culture in Central Eastern Europe 1st CEI VENICE FORUM Venice, 9-10 June 2003 Main Lecture Hall, Academy of Fine Art of Venice, Dorsoduro 1050 Monday 9 June 2003: 3pm-6pm Tuesday 10 June 2003: 9.30am-1pm and 2.30pm-6pm Programme Monday 9 June 2003 Main Hall of the Academy of Fine Arts of Venice Session starts at 3pm, Working language: english 15.00 - 15.15 Registration (outdoor desk, Academy of Fine Arts courtyard) INTRODUCTION 15.15 - 16.00 Welcome speech by: -Prof. Riccardo Rabagliati - Director of Academy of Fine Arts -Amb. Harald Kreid - Director General of CEI Executive Secretariat -Dr. Enrico Tantucci - Chief Editor Trieste Contemporanea magazine SESSION 1: Assessing the role of networks & networking in the promotion of contemporary art and culture 16. 00 - 17.45 Open Debate with focus presentations on relevant experiences Sub-sections/guidelines: -Defining network e networking -Current practices in international networkorking and cooperation I_CAN, Jerzy Onuch (Director, CCA Founadtion Kiev, Ukraine) -Coproduction: available models and tools Mucsarnok, Julia Fabenyi (Director, Mucsarnok, Budapest, Hungary) -Funding opportunities and curatorial independence Report on Belarus, Inna Reut (I-Gallery, Minsk; Belarus) 17.45 - 18.00 Closing remarks for day 1 -Summary of debate -Agenda for following day -Registration of participants to Session 2 - Working Group -Info and details for the evening 20.00 Meeting in Campo San Maurizio for dinner Restaurant: DA MARIO, San Marco 2614 Tel 041 5285968 Tuesday 10 June 2003 -

Ukraine Page 1 of 39

2009 Human Rights Reports: Ukraine Page 1 of 39 Home » Under Secretary for Democracy and Global Affairs » Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor » Releases » Human Rights Reports » 2009 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices » Europe and Eurasia » Ukraine 2009 Human Rights Reports: Ukraine BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2009 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices March 11, 2010 Ukraine, with a population of 46 million, is a multiparty, democratic republic with a parliamentary-presidential system of government. Executive authority is shared by a directly elected president and a unicameral Verkhovna Rada (parliament), which selects a prime minister as head of government. Elections in 2007 for the 450-seat parliament were considered free and fair. A presidential election is scheduled for January 2010. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces. Human rights problems included reports of serious police abuse, beatings, and torture of detainees and prisoners; harsh conditions in prisons and detention facilities; arbitrary and lengthy pretrial detention; an inefficient and corrupt judicial system; and incidents of anti-Semitism. Corruption in the government and society was widespread. There was violence and discrimination against women, children, Roma, Crimean Tatars, and persons of non-Slavic appearance. Trafficking in persons continued to be a serious problem, and there were reports of police harassment of the gay community. Workers continued to face limitations to form and join unions, and to bargain collectively. During the year the government established the Office of the Governmental Commissioner for Anticorruption Policy, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Prosecutor General's Office introduced a new system to improve the recording of hate-motivated crimes. -

Pci Brch Winter 2014 Pr

350 350 FIFTH SUITE 4621 AVENUE, WWW.POLISHCULTURE-NYC.ORG NEW 10118 YORK, NY POLISH CULTURAL INSTITUTE NEW YORK wi Nter/spriNg/2014 pci-NY wiNter / spriNg 2014 FiLM 2-9 fiLM seasoN 2014 art 10-17 PAWEŁ aLtHaMer at tHe New MuseuM Music 18-23 UNsouND FestiVaL New YorK 2014 32-35 GENeratioN '70 Literature & HuMaNities 24-29 ADaM MicHNiK at peN worLD Voices 30-31 BooKeXpo aMerica 2014 aBout us 36 PoLisH cuLturaL iNstitute New YorK LOGO FINAL C=0, M=100, Y=100, K=0 and black k=100 Pantone chip 73-1 letter from the director We ring in 2014 celebrating the success of Poland's democratic transformation, with the belief that our accomplishments thus far may inspire our neighbors and friends whom we join in solidarity, as the world joined us in solidarity, when we took our first steps toward building an open democratic society. In times of remarkably dynamic technological, political, and social change, culture and art mark the horizon that allows us to imagine a future that is both new and anchored in history. The Polish Cultural Institute New York will not remain on the sidelines, but will take up this change, inviting our followers to join us in a series of particularly interesting events for the first half of the year. The beginning of the season unveils the extraordinary presence of Polish cinema on the programs of several important New York institutions. We open in January at the New York Jewish Film Festival with director Paweł Pawlikowski’s Gdynia Film Festival winner, Ida, a work that surprised us all with its way of revealing the personal experience of the heroine who is saved from the Holocaust. -

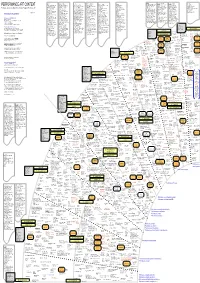

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

Download 2000 7A*11D Poster (PDF)

International Festival of Performance Art 2000 October 25 to November 5 Festival Hotline 416.822.3219 Strangeways Clive Robertson (Kingston) SU-EN Butoh Co. (Sweden) Vida Simon (Montreal) Steve Venright (Toronto) BODY+BLOOD, PICTURE+SOUND <<Videodrome>> Stefanie Marshall (Toronto) Ingrid Z (Toronto) Ben Patterson (US/Germany) Stephen Rife (USA) Prognosis Miss Barbra Fisçh (Toronto) James Luna [Luiseño] Shawan Johnston (Toronto) Mischelle Kasprzak (Toronto) Flicker, Skip, Moan Mike Stevenson (Toronto) Lisa Deanne Smith (Toronto) Jubal Brown (Toronto) Karma Clarke Davis (Toronto) Performances Zöe Stonyk (Toronto) Sylvain Breton (Toronto) Lance McLean (Toronto) Public Spaces / Private Places presented by FADO John Porter (Toronto) otiose (UK) Leena Raudvee (Toronto) Jerzy Onuch (Poland/Ukraine) Pam Patterson (Toronto) Tagny Duff (Vancouver) Christine Carson (Toronto) Master Class 5 Jessica Lertvilai (Toronto) And Terril Calder (Toronto) Jill Orr (Australia) Will Kwan (Toronto) S. Higgins (Toronto) October 25 October 27 Festival Kick Off 8 pm James Lunas (Luiseño) $10 YYZ American Indian Study’s 8 pm 401 Richmond St. W. Workman Theatre, 1001 Queen St.W. book launch for Live at the End of the Century performance by otiose YYZ gallery opening. October 28 Artist Talk:James Luna 2 pm Innis College Town Hall,2 Sussex Ave. October 26 & 27 Jill Orr(Australia) Presence 8 pm Pam Patterson/ John Porter (Toronto) LeenaRaudvee (Toronto) Remember Rings 9:30 pm Passing 1 to 4 pm Art System,327 Spadina Ave. 401 Richmond St.W. Main Hallway October 26 October 30 Steve Venright (Toronto) Jerzy Onuch (Poland/Ukraine) T.V.I.Reality Check Between Us 7:30 pm for an update on current location and SU-EN Butoh Co. -

Karen Adams for New Toronto Ratepayers Comments

GL16.6.46 From: New Toronto Rate Payers To: councilmeeting Cc: Karen Adams Subject: Comments for 2020.GL16.6 on October 27, 2020 City Council Date: October 26, 2020 1:30:07 PM Attachments: New Toronto Ratepayers Association letter to City Council.docx New Toronto Ratepayers Petition opposing purchase of 29502970 Lake Shore for a shelter.pdf New Toronto Ratepayers Association_Petition Signatures 1_Opposition to Shelter at 2950 and 2970 Lake Shore Blvd. West_September 2020.pdf New Toronto Ratepayers Association_Petition Signatures 2_Opposition to Shelter at 2950 and 2970 Lake Shore Blvd. West_September 2020.pdf To the City Clerk: Please add the attached comments to the agenda for the October 27, 2020 City Council meeting on item 2020.GL16.6, Co-location of Housing and Service Integration at 2950 and 2970 Lake Shore Boulevard West I understand that these comments and the personal information in this email will form part of the public record and that my name will be listed as a correspondent on agendas and minutes of City Council or its committees. Also, I understand that agendas and minutes are posted online and my name may be indexed by search engines like Google. Sincerely, Karen Adams for New Toronto Ratepayers Comments: To City Council As residents and business owners of New Toronto, we strongly oppose the locations at 2950 & 2970 Lake Shore Boulevard West, at the main commercial intersection in New Toronto, for use as a shelter. While we do not dispute the need for shelter beds in Ward 3, or anywhere else in the City of Toronto, and recognize the need to support the marginalized and vulnerable populations in our City especially during the pandemic, we are overwhelmingly united as a community in opposition to a shelter in the heart of New Toronto’s small commercial strip. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2016

No. 3 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY 17, 2016 5 2015: THE YEAR IN REVIEW As war in east continues, Ukraine moves Westward ocket attacks in the east marked the beginning of 2015 for Ukraine. Twelve civilians were killed and R11 were wounded by a missile fired by Russian- backed militants that hit a bus in the town of Volnovakha, 35 kilometers southwest of Donetsk, on January 13. President Petro Poroshenko stated: “This is a disaster and a tragedy for Ukraine. This is more evidence after the MH17 plane, after the many civilian casualties – it is a crime that terrorists from the so-called DNR and LNR [Donetsk and Luhansk peoples’ republics] have severely violated my peace plan, which was approved and support- ed by the European Council and the European Union.” It was yet more evidence also that the ceasefire agreed to in Minsk in September of 2014 was being violated almost daily. As of the beginning of 2015, it was noted that over 4,700 people had been killed and more than 10,000 injured in the fighting in Ukraine’s east that began in April 2014. At year’s end, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights reported that there were now more than 28,000 casualties in Ukraine since the war began, www.president.gov.ua including more than 9,000 killed. In addition to the dead At the Minsk summit on February 12 (front row, from left) are: French President Francois Hollande, Ukrainian and wounded, more than 1.5 million were internally dis- President Petro Poroshenko, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Belarusian President Alyaksandr placed as a result of the conflict. -

Overcoming Obstacles. LGBT Situation in Ukraine in 2018 / Nash Mir Center

LGBT Human Rights Nash Mir Center OVERCOMING OBSTACLES LGBT SITUATION IN UKRAINE IN 2018 Kyiv 2019 УДК 316.343-055.3(477) Overcoming obstacles. LGBT situation in Ukraine in 2018 / Nash Mir Center. - K .: Nash Mir Center, 2019. – 61 pages. This publication presents information that reflects the social, legal and political situation of the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) people in Ukraine in 2018. It contains data and analyses of the issues related to LGBT rights and interests in legislation, public and political life, and public opinion, and provides examples of discrimination on ground of sexual orientation or gender identity and more. Authors: Andrii Kravchuk, Oleksandr Zinchenkov Project Manager of Nash Mir Center: Andriy Maymulakhin The authors express their gratitude to LGBT organisations and individual activists as well as all active participants of e-mail lists and Facebook groups who collect and exchange up-to-date information on various aspects of the LGBT situation in Ukraine. We also thank J. Stephen Hunt (Chicago, IL) for proofreading the English translation and making other contributions to this publication. This report was prepared according to results obtained through monitoring and human rights defending activities by Nash Mir Center. In 2018 they were supported by the British Embassy in Ukraine, Tides Foundation (USA), the Human Rights Fund of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, and the State Department of the USA. Opinions expressed by the report’s authors are solely theirs, and should not be considered as the official position of any of the donors to Nash Mir Center. LGBT Human Rights Nash Mir Center Postal address: P.O. -

ECFG-Ukraine-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: Ukrainian and Polish soldiers compete in a soccer during cultural day at the International Peacekeeping and Security Center in Yavoriv, Ukraine). The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Eastern Europe. Ukraine Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Ukrainian society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre-deployment training (Photo: A Ukrainian media woman dances as the US Air Forces in Europe Band plays a song in Dnipro, Ukraine). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments.