Part IV: the State Stratum-Of-Being

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japan Between the Wars

JAPAN BETWEEN THE WARS The Meiji era was not followed by as neat and logical a periodi- zation. The Emperor Meiji (his era name was conflated with his person posthumously) symbolized the changes of his period so perfectly that at his death in July 1912 there was a clear sense that an era had come to an end. His successor, who was assigned the era name Taisho¯ (Great Righteousness), was never well, and demonstrated such embarrassing indications of mental illness that his son Hirohito succeeded him as regent in 1922 and re- mained in that office until his father’s death in 1926, when the era name was changed to Sho¯wa. The 1920s are often referred to as the “Taisho¯ period,” but the Taisho¯ emperor was in nominal charge only until 1922; he was unimportant in life and his death was irrelevant. Far better, then, to consider the quarter century between the Russo-Japanese War and the outbreak of the Manchurian Incident of 1931 as the next era of modern Japanese history. There is overlap at both ends, with Meiji and with the resur- gence of the military, but the years in question mark important developments in every aspect of Japanese life. They are also years of irony and paradox. Japan achieved success in joining the Great Powers and reached imperial status just as the territo- rial grabs that distinguished nineteenth-century imperialism came to an end, and its image changed with dramatic swiftness from that of newly founded empire to stubborn advocate of imperial privilege. Its military and naval might approached world standards just as those standards were about to change, and not long before the disaster of World War I produced revul- sion from armament and substituted enthusiasm for arms limi- tations. -

418338 1 En Bookbackmatter 205..225

Glossary Abhayamudra A style of keeping hands while sitting Abhidhama The Abhidhamma Pitaka is a detailed scholastic reworking of material appearing in the Suttas, according to schematic classifications. It does not contain systematic philosophical treatises, but summaries or enumerated lists. The other two collections are the Sutta Pitaka and the Vinaya Pitaka Abhog It is the fourth part of a composition. The last movement gradually goes back to the sthayi after completion of the paraphrasing and improvisation of the composition, which can cover even three octaves in the recital of a master performer Acharya A teacher or a tutor who is the symbol of wisdom Addhayoga One of seven kinds of lodgings where monks are allowed to live. Addhayoga is a building with a roof sloping on either one side or both. It is shaped like wings of the Garuda Agganna-sutta AggannaSutta is the 27th Sutta of the Digha Nikaya collection. The sutta describes a discourse imparted by the Buddha to two Brahmins, Bharadvaja, and Vasettha, who left their family and caste to become monks Ahankar Haughtiness, self-importance A-hlu-khan mandap Burmese term, a temporary pavilion to receive donation Akshamala A japa mala or mala (meaning garland) which is a string of prayer beads commonly used by Hindus, Buddhists, and some Sikhs for the spiritual practice known in Sanskrit as japa. It is usually made from 108 beads, though other numbers may also be used Amulets An ornament or small piece of jewellery thought to give protection against evil, danger, or disease. Clay tablets have also been used as amulets. -

25878784.Pdf

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 124 International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2017) The Sprout of Foreign Contact Reflected in "The Secret History of Mongolia" The Contact with Other Tribes and Neighboring Countries Xuelian History and Culture College Chifeng University Inner Mongolia, China Abstract—In the Mongolian classical literature "the secret relevant Mongolian tribes foreign relations. In many history of Mongolia,", it can learn about the sprout of foreign historical books, the only book which was written in the relations in the original Mongolia tribes - and other tribes, the thinking of Mongolian language is "the secret history of contact between the neighboring countries was the main clue to Mongolia", which is not only describing the early Mongolian the diplomacy during this period. Among it, the people who prairie social life style of the heroic epic, but also we know have served as the bridge and bond between the tribes and the that the original data of the foreign relation activity in that countries was the "Elechi" envoy. time. If we trace the origin of the origin of foreign relations in Mongol-Yuan period, we must begin with the relevant Keywords—the history of Mongolia; foreign relations; Elechi records and narration in "the secret history of Mongolia". "The secret history of Mongolia" described the origin of the I. INTRODUCTION Mongols in detail, the story of Lord Genghis khan and Cuy Human beings are the social group, and their diplomatic kaan period, and the establishment of the Mongol khanate, activities have a long history. -

Land Use and Land Tenure in Mongolia: a Brief History and Current Issues Maria E

Land Use and Land Tenure in Mongolia: A Brief History and Current Issues Maria E. Fernandez-Gimenez Maria E. Fernandez-Gimenez is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Forest, Rangeland, and Watershed Stewardship at Colorado State University. She received her PhD at the University of California, Berkeley in 1997 and has conducted research in Mongolia since 1993. Her current areas of research include pastoral development policy; community-based natural resource management; traditional and local ecological knowledge; and monitoring and adaptive management in rangeland ecosystems. strategies have not changed greatly; mobile and flexible grazing Abstract—This essay argues that an awareness of the historical relation- ships among land use, land tenure, and the political economy of Mongolia strategies adapted to cope with harsh and variable production is essential to understanding current pastoral land use patterns and policies conditions remain the cornerstone of Mongolian pastoralism. in Mongolia. Although pastoral land use patterns have altered over time in Similarly, although land tenure regimes have evolved towards response to the changing political economy, mobility and flexibility remain increasingly individuated tenure over pastoral resources, hallmarks of sustainable grazing in this harsh and variable climate, as do the communal use and management of pasturelands. Recent changes in Mongolia’s pasturelands continue to be held and managed as common political economy threaten the continued sustainability of Mongolian pastoral property resources in most locations, although these institutions systems due to increasing poverty and declining mobility among herders and have been greatly weakened in the past half century. The most the weakening of both formal and customary pasture management institu- recent changes in Mongolia’s political economy threaten the tions. -

Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi POWER, POLITICS, AND TRADITION IN THE MONGOL EMPIRE AND THE ĪlkhānaTE OF IRAN OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Īlkhānate of Iran MICHAEL HOPE 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6D P, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Michael Hope 2016 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2016932271 ISBN 978–0–19–876859–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Cyrtopodion Baturense (Khan and Baig 1992) and Cyrtopodion Walli (Ingoldby 1922) (Sauria: Gekkonidae)

Zootaxa 2636: 1–20 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Studies on Pakistan Lizards: Cyrtopodion baturense (Khan and Baig 1992) and Cyrtopodion walli (Ingoldby 1922) (Sauria: Gekkonidae) KURT AUFFENBERG1,4, KENNETH L. KRYSKO2 & HAFIZUR REHMAN3 1Florida Museum of Natural History, Powell Hall, P. O. Box 112710, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Florida Museum of Natural History, Division of Herpetology, P.O. Box 117800, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 3Zoological Survey Department, Government of Pakistan, Karachi 72400 Pakistan 4Corresponding author Abstract The taxonomy of Eurasian angular or thin-toed geckos has undergone a great deal of revision over the last 30 years. However, it is clear that a desirable level of taxonomic resolution has not yet been attained as their taxonomic assignments are somewhat arbitrary. In this paper, we discuss two lesser-known gecko species, Cyrtopodion baturense (Khan and Baig 1992) and C. walli (Ingoldby 1922). One adult specimen of Cyrtopodion baturense (the only known specimen other than the type series) and a series of 53 C. walli collected by Walter Auffenberg and the Zoological Survey Department of Pakistan (ZSD) and subsequently deposited in the University of Florida Herpetology collection were compared to the type specimens. Specimens were examined for 46 morphological characters and measurements. Cyrtopodion baturense and C. walli are diagnosable and confirmed to be distinct species. Cyrtopodion baturense is known only from the holotype locality of Pasu and the nearby village of Dih, Hunza District, in the Gilgit Agency, Federally Administered Northern Areas (FANA), Pakistan, at 2,438–3,078 m elevations. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

The Great Empires of Asia the Great Empires of Asia

The Great Empires of Asia The Great Empires of Asia EDITED BY JIM MASSELOS FOREWORD BY JONATHAN FENBY WITH 27 ILLUSTRATIONS Note on spellings and transliterations There is no single agreed system for transliterating into the Western CONTENTS alphabet names, titles and terms from the different cultures and languages represented in this book. Each culture has separate traditions FOREWORD 8 for the most ‘correct’ way in which words should be transliterated from The Legacy of Empire Arabic and other scripts. However, to avoid any potential confusion JONATHAN FENBY to the non-specialist reader, in this volume we have adopted a single system of spellings and have generally used the versions of names and titles that will be most familiar to Western readers. INTRODUCTION 14 The Distinctiveness of Asian Empires JIM MASSELOS Elements of Empire Emperors and Empires Maintaining Empire Advancing Empire CHAPTER ONE 27 Central Asia: The Mongols 1206–1405 On the cover: Map of Unidentified Islands off the Southern Anatolian Coast, by Ottoman admiral and geographer Piri Reis (1465–1555). TIMOTHY MAY Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. The Rise of Chinggis Khan The Empire after Chinggis Khan First published in the United Kingdom in 2010 by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX The Army of the Empire Civil Government This compact paperback edition first published in 2018 The Rule of Law The Great Empires of Asia © 2010 and 2018 Decline and Dissolution Thames & Hudson Ltd, London The Greatness of the Mongol Empire Foreword © 2018 Jonathan Fenby All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced CHAPTER TWO 53 or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, China: The Ming 1368–1644 including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

Iron Age Nomads of Southern Siberia in Craniofacial Perspective

ANTHROPOLOGICAL SCIENCE Vol. 122(3), 137–148, 2014 Iron Age nomads of southern Siberia in craniofacial perspective Ryan W. SCHMIDT1,2*, Andrej A. EVTEEV3 1University of Montana, Department of Anthropology, Missoula, MT 59812, USA 2Kitasato University, School of Medicine, Department of Anatomy, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 252-0374, Japan 3Anuchin Research Institute and Museum of Anthropology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, 125009, Mokhovaya St., 11, Russia Received 9 April 2014; accepted 24 July 2014 Abstract This study quantifies the population history of Iron Age nomads of southern Siberia by ana- lyzing craniofacial diversity among contemporaneous Bronze and Iron Age (7th–2nd centuries BC) groups and compares them to a larger geographic sample of modern Siberian and Central Asian popula- tions. In our analyses, we focus on peoples of the Tagar and Pazyryk cultures, and Iron Age peoples of the Tuva region. Twentysix cranial landmarks of the vault and facial skeleton were analyzed on a total of 461 ancient and modern individuals using geometric morphometric techniques. Male and female cra- nia were separated to assess potential sexbiased migration patterns. We explore southern Siberian pop- ulation history by including Turkicspeaking peoples, a Xiongnu Iron Age sample from Mongolia, and a Bronze Age sample from Xinjiang. Results show that male Pazyryk cluster closer to Iron Age Tuvans, while Pazyryk females are more isolated. Conversely, Tagar males seem more isolated, while Tagar fe- males cluster amongst an Early Iron Age southern Siberian sample. When additional modern Siberian samples are included, Tagar and Pazyryk males cluster more closely with each other than females, sug- gesting possible sexbiased migration amongst different Siberian groups. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

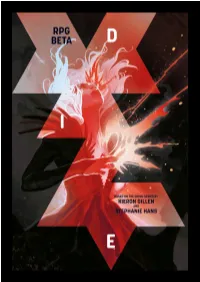

DIE RPG Beta Manual V1.Pdf

DIE: A ROLE-PLAYING GAME KIERON GILLEN ©2019 ART BY STEPHANIE HANS COVER DESIGN BY RIAN HUGHES Copyright © 2019 Kieron Gillen Ltd & Stéphanie Hans. All rights reserved. DIE, the Die logos, and the likenesses of all characters herein or hereon are trademarks of Kieron Gillen Ltd & Stéphanie Hans. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means (except for short excerpts for journalistic or review purposes) without the express written permission of Kieron Gillen Ltd or Stéphanie Hans. All names, characters, events, and places herein are entirely fictional. Any resemblance to actual persons (living or dead), events, or places is coincidental. Representation: Law Offices of Harris M. Miller II, P.C. ([email protected]) CONTENTS 1) INTRODUCTION 2) THE WORLD OF DIE 3) PREPARATION 4) THE FIRST SESSION 5) PREPARING THE SECOND SESSION 6) THE SECOND SESSION 7) THE RULES 8) RUNNING THE ARCHETYPES 9) ADVICE FOR GAMESMASTERS 10) OTHER RESOURCES WELCOME I have a habit of being a little extra around my comics. I fear this is the most extra thing I’ve ever done. Alongside creating the comic DIE with Stephanie Hans, I developed the role-playing game you hold in your hands. Er… figure of speech. “PDF on your hard drive” doesn’t quite have the same ring. This RPG creates, in a miniaturized form, your own version of the first arc of DIE. As such, there’s some possible structural spoilers for the comic. I say “possible” because it really is your own version of the comic. -

Lesson Title the Yuan Empire, the Silk Road and the Mongols Class

Lesson Title The Yuan Empire, the Silk Road and the Mongols Class and Grade level(s) History, Grades 6-8 Goals and Objectives The student will be able to: Identify the boundaries of the Mongol Empire Understand that Mongol rule was a time of cosmopolitan cultural exchange in China and across Asia Understand the values of the Mongol leaders that underlined this cultural exchange Understand how this might have differed from those of the Chinese dynasties that came before them, particularly the Song dynasty Understand the concept of Eurasia and the Silk Road Appreciate that a desire for global trade seen in the operation of the Silk Road foreshadowed the exploration and colonization of the Americas Connect the exchange of ideas and goods along the Silk Road to our current exchanges through the internet, and compare the spread of ideas (cultural diffusion) throughout the Mongolian Empire to the spread of American ideas throughout the world Read, understand and contextualize two primary sources. Time required/class periods needed 5 class periods, 44 minutes each. Primary source bibliography 1. Marco Polo’s description in translation at: http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/china/polo_hangzhou.pdf 2. Objects traded on the Silk Road http://www.advantour.com/silkroad/goods.htm 3. The Beijing Qing Ming Scroll, viewable at: http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/song/pop/c_scroll.htm interactive roll-over version: http://www.npm.gov.tw/exh96/orientation/flash_4/index.html Other resources used http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols/ Two lesson plans about Marco Polo’s travels: http://edsitement.neh.gov/lesson-plan/marco-polo- takes-trip http://edsitement.neh.gov/curriculum-unit/road-marco-polo (This one has an interactive map that allows students to take Polo’s route by answering questions about his travels) Required materials/supplies Outline maps of Eurasia Colored pencils and paper Vocabulary Mongol, Yuan dynasty, Silk Road, Confucianism, caravan Procedure First Class Period 1.