A Place-Based Turn in Multifunctional Agriculture: the Case of Italy's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19110 Grosseto 5:00 Siena 6:29 Cancellato Sostituito Con Bus Con Fermata a Civitella Paganico

Ora di Categoria Treno Origine Destinazione Ora di arrivo Provvedimento Note partenza R 19110 Grosseto 5:00 Siena 6:29 Cancellato Sostituito con bus con fermata a Civitella Paganico Sostituito con bus con fermata a Pisa San Rossore, San Giuliano Terme, Rigoli, Ripafratta, Lucca, Diecimo Pescaia, Bagni di Lucca, R 19145/19146 Pisa Centrale 5:25 Aulla Lunigiana 8:07 Cancellato Fornaci, Castelnuovo Garfagnana, Piazza al Serchio, Minucciano, Gragnola R 19067 Siena 6:00 Chiusi 7:21 Cancellato Sostituito con bus con fermata a Asciano, Sinalunga R 18553 Pisa Centrale 7:04 Lucca 7:36 Cancellato Sostituito con bus con fermata a Pisa San Rossore, San Giuliano, Rigoli, Ripafratta Sostituito con bus con fermata a Firenze Campo Marte, Sieci, Pontassieve, Rufina, Scopeti, Contea, Dicomano, Vicchio, Borgo San R 18939 Firenze Santa Maria Novella 7:55 Borgo San Lorenzo 9:10 Cancellato Lorenzo Rimorelli R 18622 Lucca 7:59 Viareggio 8:26 Cancellato Sostituito con bus con fermata a Nozzano, Massarosa Sostituito con bus con fermata a Gragnola, Minucciano, Piazza al Serchio, Castelnuovo Garfagnana, Fornaci, Bagni di Lucca, Diecimo R 19161/19162 Aulla Lunigiana 8:28 Pisa Centrale 11:13 Cancellato Pescaia, Lucca, Ripafratta, San Giuliano, Pisa San Rossore R 19074 Chiusi 8:30 Siena 9:50 Cancellato Sostituito con bus con fermata a Sinaluga, Asciano R 18556 Lucca 8:42 Pisa Centrale 9:13 Cancellato Sostituito con bus con fermata a Pisa San Rossore, San Giuliano, Rigoli, Ripafratta R 18625 Viareggio 8:51 Lucca 9:20 Cancellato Sostituito con bus con fermata a Massarosa, -

Biodynamic Agriculture

Biodynamic Agriculture Economic Botany Dr. Uma Garimella University of Central Arkansas April 19, 2007 Sustainable Agriculture • Movement that emerged in the 1970’s • Serves to address the Environmental and Social concerns brought on by modern, industrial agriculture • Three Main Goals: – Environmental Stewardship – Farm Profitability – Prosperous Farming Communities Sustainable Agriculture Can be divided into three branches: 1. Organic 2. Biodynamic 3. Indore Process Organic • An ecological production management system that promotes and enhances: – Biodiversity – Biological cycles – Soil biological activity • Based on minimal use of off-farm inputs and on management practices that - restore, maintain & enhance ecological harmony. Organic Agriculture production without the use of synthetic chemicals such as fertilizers, pesticides, and antibiotics. Biodynamic • Incorporates the beneficial use of the cosmic energies into the cultivation of plants. • Systematic inputs of mineral, plant and animal nutrient to the field. • Cultivation practices are carried out according to the biodynamic calendar. One of the biodynamic farming practices is to bury cow horns filled with organic cow manure. After being underground for about five months, the compost is removed and made into a tea, which is spread around vineyards and farms. Indore Process • Manufacture of humus from vegetable & animal waste • Developed at the Institute of Plant Industry in Indore, India & brought to “us” by Sir Albert Howard • Determined the maintenance of soil fertility is the real basis of health and of resistance to disease. Various parasites were found to be only secondary matters: their activities resulted from the breakdown of a complex biological system -- the soil in its relation to the plant and to the animal -- due to improper methods of agriculture, an impoverished soil, or to a combination of both. -

Star-And-Furrow-110.Pdf

JOURNAL OF THE BIODYNAMIC AGRICULTURAL ASSOCIATION ■ ISSUE NO: 110 ■ WINTER 2009 ■ ISSN NO: 1472-4634 ■ £4.50 INTERVIEW WITH ALAN BROCKMAN SUSTAINABLE ENERGY ON A BIODYNAMIC FARM A NEW APPROACH TO MILLING AND BAKING GARDEN PLANNING AT PISHWANTON Demeter Certifi cation STAR & FURROW The Association owns and administers the Journal of the Biodynamic Agricultural Association Demeter Certifi cation Mark that is used by Published twice yearly biodynamic producers in the UK to guaran- Issue Number 110 - Winter 2009 THE BIODYNAMIC tee to consumers that internationally recog- ISSN 1472-4634 AGRICULTURAL nised biodynamic production standards are ASSOCIATION (BDAA) being followed. These standards cover both production and processing and apply in more STAR & FURROW is the membership magazine The Association exists in order to sup- than forty countries. They are equivalent to of The Biodynamic Agricultural Association port, promote and develop the biodynamic or higher than basic organic standards. The (BDAA). It is issued free to members. approach to farming, gardening and forestry. Demeter scheme is recognised in the UK as Non members can also purchase Star and This unique form of organic husbandry is Organic Certifi cation UK6. Furrow. For two copies per annum the rates are: inspired by the research of Rudolf Steiner UK £11.00 including postage (1861-1925) and is founded on a holistic and Apprentice Training Europe (airmail) £13.00 spiritual understanding of nature and the A two year practical apprentice training Rest of the World (airmail) £16.00 human being. course is offered in biodynamic agriculture and horticulture. Apprentices work in ex- Editor: Richard Swann, Contact via the BDAA The Association tries to keep abreast of change for board and lodging on established Offi ce or E-mail: [email protected] developments in science, nutrition, education, biodynamic farms and gardens and receive Design & layout: Dave Thorp of ‘The Workshop’ health and social reform. -

Biodynamic Agriculture.Pdf

CHAPTER-2 BIODYNAMIC AGRICULTURE Biodynamic agriculture is a form of alternative agriculture very similar to organic farming, but it includes various esoteric concepts drawn from the ideas of Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925). Initially developed in 1924, it was the first of the organic agriculture movements. It treats soil fertility, plant growth, and livestock care as ecologically interrelated tasks, emphasizing spiritual and mystical perspectives. Biodynamic has much in common with other organic approaches – it emphasizes the use of manures and composts and excludes the use of artificial chemicals on soil and plants. Methods unique to the biodynamic approach include its treatment of animals, crops, and soil as a single system, an emphasis from its beginnings on local production and distribution systems, its use of traditional and development of new local breeds and varieties. Some methods use an astrological sowing and planting calendar. Biodynamic agriculture uses various herbal and mineral additives for compost additives and field sprays; these are prepared using methods that are more akin to sympathetic magic than agronomy, such as burying ground quartz stuffed into the horn of a cow, which are said to harvest "cosmic forces in the soil." As of 2016 biodynamic techniques were used on 161,074 hectares in 60 countries. Germany accounts for 45% of the global total; the remainder average 1750 ha per country. Biodynamic methods of cultivating grapevines have been taken up by several notable vineyards. There are certification agencies for biodynamic products, most of which are members of the international biodynamic standards group Demeter International. No difference in beneficial outcomes has been scientifically established between certified biodynamic agricultural techniques and similar organic and integrated farming practices. -

Barga Summer Guide What, When & Where

IN ENGLISH VERSIONE ITALIANA SUll’altro lato inBARGA EVENTS • PLACES • FOOD & DRINK • accommodation • SHOPS & serviCES BARGA SUMMER GUIDE WHAT, WHEN & WHERE 2020 EDITION Il Giornale di BARGA VisitBarga.com arga is a pearl set in the Serchio Valley: Ba place of unique beauty that touches us profoundly. Its history is linked to that of the Poet Giovanni Pascoli who lived here and wrote some of his most famous poetry. But it also goes back many centuries and is reflected in the charm of our medieval town. This year “InBarga” has been adapted to the Coronavirus period that has overturned many moments and routines of our daily life and has forced us to re-plan all the events. We want to give you, for this reason, the opportu- nity to discover in these pages, a way to spend an unforgettable and alternative holiday in Barga despite these difficult moments. We invite you to wander around the streets and lanes completely absorbed in history, charm, sounds, scents, colours and welcom- ing warmth of the people. You will discover for sure why Barga and the surrounding places have always been a favourite destination for artists in search of inspiration and of a special Eden. You will fall in love with it too. inBARGA SUPPLEMENT TO IL GIORNALE DI BARGA NUMBER 835 DEL MAGGIO 2020 VIA DI BORGO, 2 – 55051 BARGA LU EXECUTIVE EDITOR: LUCA GALEOTTI TEXTS: SARA MOSCARDINI ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS: SONIA ERCOLINI GRAPHIC AND LAYOUT: CONMECOM DI MARCO TORTELLI PUBLISHING: SAN MARCO LITOTIPO SRL, LUCCA WITH THE CONTRIBUTION OF Società Benemerita Giovanni Pascoli -

Certifying Spirituality Biodynamics in America- Sarah Olsen MAFS Thesis

chatham F ALK SCHOOL OF SUST AINABILITY & ENVIRONMENT Master of Arts in Food Studies The Undersigned Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis of Sarah Olsen on April 26, 2019 "Certifying Spirituality: Biodynamics in America" Nadine Lehrer, Ph.D., Chair Assistant Professor, Food Studies, Chatham University Frederick Kirschenmann Distinguished Fellow, Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture This thesis is accepted in its present form by the Falk School of Sustainability as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Food Studies Certifying Spirituality: Biodynamics in America A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Masters of Food Studies Chatham University Sarah Olsen May 2019 Contents 1. Introduction -1 1.1 Background 2. Literature Review - 5 2.1 Spirituality and Agriculture - 5 2.2 History and Practice of Biodynamics - 12 2.3 Organics in the U.S. - 21 3. Methods - 23 4. Results- 35 4.1 Conference Participant Observation -35 4.1 Survey Results- 40 5. Conclusion - 59 6. Works Cited- 66 7. Appendix A- 68 Certifying Spirituality: Biodynamics in America Introduction: First described by Rudolf Steiner in a series of lectures in 1924, biodynamics is an agri- cultural model that focuses on the farm as an organism that can be affected, both positively and negatively, by the farmers interacting with the spiritual (non-physical) world. In other words, ac- cording to Steiner, the ways in which a farmer tends his/her plants and animals in relation to planetary phases and movements, and his/her treatment of spiritual creatures, all influence physi- cal properties of the earth and therefore the functioning of his/her farm (Steiner, 1993). -

Valle Del Serchio Settembre 2020 + Inv

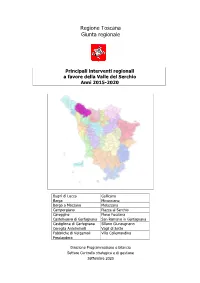

Regione Toscana Giunta regionale Principali interventi regionali a favore della Valle del Serchio Anni 2015-2020 Bagni di Lucca Gallicano Barga Minucciano Borgo a Mozzano Molazzana Camporgiano Piazza al Serchio Careggine Pieve Fosciana Castelnuovo di Garfagnana San Romano in Garfagnana Castiglione di Garfagnana Sillano Giuncugnano Coreglia Antelminelli Vagli di Sotto Fabbriche di Vergemoli Villa Collemandina Fosciandora Direzione Programmazione e bilancio Settore Controllo strategico e di gestione Settembre 2020 INDICE ORDINE PUBBLICO E SICUREZZA .................................................................................................. 3 SISTEMA INTEGRATO DI SICUREZZA URBANA.....................................................................................................3 ISTRUZIONE E DIRITTO ALLO STUDIO ..........................................................................................3 TUTELA E VALORIZZAZIONE DEI BENI E DELLE ATTIVITÀ CULTURALI.......................................... 3 POLITICHE GIOVANILI, SPORT E TEMPO LIBERO..........................................................................4 SPORT E TEMPO LIBERO....................................................................................................................................4 GIOVANI...........................................................................................................................................................4 TURISMO........................................................................................................................................4 -

Camporgiano, Camporeggiano

Dizionario Geografico, Fisico e Storico della Toscana (E. Repetti) http://193.205.4.99/repetti/ Camporgiano, Camporeggiano ID: 825 N. scheda: 10090 Volume: 1 Pagina: 434 - 437 ______________________________________Riferimenti: Toponimo IGM: Camporgiano Comune: CAMPORGIANO Provincia: LU Quadrante IGM: 096-2 Coordinate (long., lat.) Gauss Boaga: 1606788, 4890320 WGS 1984: 10.33634, 44.15985 ______________________________________ UTM (32N): 606852, 4890495 Denominazione: Camporgiano, Camporeggiano Popolo: S. Jacopo a Camporgiano Piviere: S. Pietro a Piazza e Sala Comunità: Camporgiano Giurisdizione: Camporgiano Diocesi: (Luni - Sarzana) Massa Ducale Compartimento: x Stato: Ducato di Modena ______________________________________ CAMPORGIANO già CAMPOREGGIANO in Garfagnana ( Campus Regianus ). Castello sulla ripa destra del Serchio con chiesa prioria (S. Jacopo), capoluogo di Comunità, residenza di un Giusdicente, nel Governo di Castelnuovo, Diocesi di Massa Ducale, già di Sarzana, Ducato di Modena. Risiede in un ripiano a mezza costa presso alla confluenza del fosso Vitojo alla destra del Serchio, sopra una rupe di macigno brecciato, che si modifica in una roccia serpentinosa, rupe che scende quasi a picco nell'alveo del Serchio, sul cui lembo si trova il pretorio, già castello difeso da 4 torri unite da altrettante cortine. Trovasi nel grado 27° 59' 4” di longitudine 44° 9' 5” di latitudine, 6 miglia toscane a maestro di Castelnuovo di Garfagnana; 11 miglia toscane idem da Barga; 30 a settentrione di Lucca; 15 miglia toscane a grecale di Massa Ducale, varcando l'Alpe Apuana per la via della Tambura. La rocca di Camporgiano, architettata nel secolo XIV, fu destinata sino d'allora a residenza dei giusdicenti della Vicarìa di questo nome, la quale abbracciava l'alta Garfagnana, consistente in 43 ville, situate presso che tutte nell'antico plebanato di Piazza , compreso nella Diocesi di Luni. -

What Is Biodynamics? by Sherry Wildfeuer

What Is Biodynamics? by Sherry Wildfeuer What do you think a human being really is? Your answer to this question will determine the character of your actions towards other people. If you conceive of yourself and all humans as wisely fashioned divine creations with a capacity for love which can only be achieved through one’s own activity, you will be more likely to take an interest in other people and their development. If you see humanity as an accidental product of physical processes occurring randomly in the universe, it may be more difficult to find the motivation for earnest and consistent work on yourself and for others. The same holds true for your concept of nature. Ours is not a philosophically oriented culture, yet we are strongly influenced by the unspoken philosophy of materialism that prevails in our education. Thus we are led to accept actions towards the earth that are the consequences of a mechanistic view of living creatures and their mutual relations. Biodynamic agriculture springs from a spiritual world view known as anthroposophy. The Austrian philosopher and seer Rudolf Steiner developed a new approach to science which integrates precise observation of natural phenomena, clear thinking, and knowledge of the spirit. It offers an account of the spiritual evolution of the Earth as a living being, and of the constitution of the human being and the kingdoms of nature. Rudolf Steiner gave a series of lectures in 1924 in response to questions brought by farmers who noticed even then a deterioration in seed quality and animal fertility. Practitioners and experimenters over the last 70 years have added tremendously to the body of knowledge known as biodynamics. -

Vagli Di Garfagnana - Vagli Sotto - Terrenuove Della Garfagnana

Dizionario Geografico, Fisico e Storico della Toscana (E. Repetti) http://193.205.4.99/repetti/ Vagli di Garfagnana - Vagli Sotto - Terrenuove della Garfagnana ID: 4263 N. scheda: 52490 Volume: 5 Pagina: 519, 619 ______________________________________Riferimenti: 52480 Toponimo IGM: Vagli di sotto Comune: VAGLI SOTTO Provincia: LU Quadrante IGM: 096-2 Coordinate (long., lat.) Gauss Boaga: 1603189, 4884924 WGS 1984: 10.29028, 44.11179 ______________________________________ UTM (32N): 603252, 4885098 Denominazione: Vagli di Garfagnana - Vagli Sotto - Terrenuove della Garfagnana Popolo: S. Regolo a Vagli Sotto Piviere: S. Pietro a Piazza e Sala Comunità: Vagli Sotto Giurisdizione: Camporgiano Diocesi: (Luni - Sarzana) Massa Ducale Compartimento: x Stato: Ducato di Modena ______________________________________ TERRENUOVE DELLA GARFAGNANA nella Valle superiore del Serchio. - Le Terre e i villaggi di Sassi, Rontano, Casatico, Vitojo, di Ceserana, Vagli di sotto, Vagli di sopra, e San Donnino, che nel 24 luglio 1451 si diedero volontariamente a Borso d'Este marchese di Ferrara, si distinsero col nome di Terre Nuove , per essere state l'ultime ad eleggersi la soggezione ai marchesi Estensi, che ne formarono una vicaria sottoposta al giusdicente di Castel Nuovo della Garfagnana. - Vedere GARFAGNANA. VAGLI DI GARFAGNANA nella valle superiore del Serchio. - Due villaggi omonimi ( Vagli sopra e Vagli Sotto) danno il titolo a una Comunità , di cui è capoluogo il villaggio di Vagli sotto. Esistono entrambi i paesetti nel fianco orientale dell'alpe Apuana, detta la Tambura, lungo la strada tracciata su quell'alpe fra Castenuovo e Massa-Ducale nel secolo passato per ordine di Ercole III Duca di Modena. - Tanto l'uno come l'altro villaggio conta la sua chiesa parrocchiale (S. -

Gal Garfagnana - Comune Di Camporgiano “Centro Di Aggregazione Per Servizi Sociali a Sostegno Delle Popolazioni Rurali”

GAL GARFAGNANA - COMUNE DI CAMPORGIANO “CENTRO DI AGGREGAZIONE PER SERVIZI SOCIALI A SOSTEGNO DELLE POPOLAZIONI RURALI” GAL GARFAGNANA PSR 2007-2013 “Asse 4 - Leader” Misura 321 a): “Servizi essenziali per l’economia e la popolazione rurale” Sottomisura a) “Reti di protezione sociale nelle zone rurali” PROGETTO: Centro di aggregazione per servizi sociali a sostegno delle popolazioni rurali BENEFICIARIO: COMUNE DI CAMPORGIANO CONTESTO TERRITORIALE: Camporgiano è un comune della provincia di Lucca in Garfagnana. La Garfagnana è un’area compresa tra le Alpi Apuane e l’Appennino Tosco Emiliano. Confinante a Nord con la Lunigiana, a Ovest con la Versilia e la provincia di Massa, a Est con la regione Emilia Romagna e a Sud con la Lucchesia, è interamente attraversata dal fiume Serchio, dai suoi molti affluenti ed è ricchissima di boschi. La Garfagnana offre un'ampia varietà di paesaggi, a partire da una fascia montana impervia e incontaminata, rocciosa sulle Alpi Apuane, prativa e dal declivio più dolce in Appennino, che si trasforma alle quote minori in un collina ricca di prati e terreni coltivati di una particolare bellezza paesaggistica. Il corso del fiume Serchio la divide e segna il centro della vallata. Camporgiano sorge nell’alta valle del Serchio in Garfagnana, sulla riva destra del fiume Serchio a 475 m slm, in una valle che divide le due catene montuose delle Alpi Apuane e degli Appennini. Il territorio comprende varie frazioni comunali, poste nelle zone di poggio mentre gli abitati di più ampie dimensioni si trovano nel fondovalle (Camporgiano, Filicaia). L’aspetto del paesaggio è quello dell’alta collina: folti boschi di castagni, terreni seminativi e vasti prati. -

DISCOVERING GARFAGNANA a Walk to Catch the Past and the Present of This Hidden Corner of Tuscany

GARFAGNANA GUIDE Associazione di Guide Ambientali della Garfagnana e Mediavalle DISCOVERING GARFAGNANA A walk to catch the past and the present of this hidden corner of Tuscany WHEN: every Saturday, from April to October PARTICIPANTS: min 2 / max 16 persons LENGHT: 8 Km (5 miles) ITINERARY: downhill route through tracks, country paths and dirt roads START: 14.30 at the townhall of Villa Collemandina FACILITIES: bars and water supply in Villa Collemandina, Castiglione and Pieve Fosciana END: 18.00 in Pieve Fosciana GUIDE: Pierluigi Pellizzer, qualified local guide, member of Garfagnana Guide association, fluent English speaking PRICE (per person): 2-3 persons, 22 Euro / 4-6 persons, 12 Euro / 7-16 persons, 8 Euro. Cost covers the guiding service and should be paid before starting. DESCRIPTION HIGHLIGHTS The walk is an easy itinerary through the ✔ The walled town of Castiglione picturesque villages of the valley. The qualified ✔ The medieval humpbacked bridge local guide will talk about the landscape, the history and the economy of Garfagnana, as: ✔ San Sito church in Villa Collemandina • the Apuan Alps and Apennines mountains, with ✔ The picturesque town of Pieve Fosciana theirs parks and the marble quarries ✔ The Apuan Alps and Apennines skyline • the economy of the valley: forests and pastures • medieval villages, strongholds and fortresses • a troubled history: from the Etruscans, through the Lombards, the duchy of Lucca and Modena • the farro (emmer), the wheat's ancestor, the local protected product • the chestnut process: the 'bread tree', the harvest, the 'Metato' storing place • local fairs and traditions FOR INFO AND BOOKING Booking required by 6 pm of the day before.