Toronto School of Theology at the University of Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACADEMIC CATALOG 2019-2020 Contents

ACADEMIC CATALOG 2019-2020 Contents Mission Statement ...................................................................................................................................... 1 President’s Message ................................................................................................................................... 2 Visiting ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 History .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Regis College at a Glance ......................................................................................................................... 5 Accreditation .............................................................................................................................................. 7 The Regis Pathways of Achievement ...................................................................................................... 9 Associate Degree Programs at a Glance ............................................................................................... 13 Regis Facilities and Services................................................................................................................... 16 General College Policies and Procedures............................................................................................. 20 Accreditation, State -

Paws for a Cause

Arlington Catholic High School Paws for a Cause By Brendan Meehan Guest Reporter organization, enhances the lives of At first glance, many people people with disabilities by providing would look at my dog Ziti and as- highly trained assistance dogs and sume he is my house pet. What they on-going support to ensure quality would not know was that Ziti has a partnerships. Since then, more than very special job, and a second life. 6,000 people have been placed in the Ziti, as those who have met him program, which assures, “The assis- would know, is one of the most en- tance dogs we breed, raise, and train ergetic and excited dogs one could aren’t just the ears, hands, and legs ever meet. Ziti, however, has a of their human partners. They’re softer side as a service dog in train- also goodwill ambassadors, and ing. Service animals can be defined often their best friends. They open as animals who have specialized up new opportunities and new pos- training to enable the greater in- sibilities, and spread incredible joy.” dependence of another being. For I’ve been raising these animals me, Ziti proves to be another fine since middle school, and Ziti is the example of the time and effort that third dog that I have fostered. In go into training a service animal. his time with me, he will learn over Founded in 1975, Canine Compan- forty commands, become an out- ions for Independence, a non-profit standing candidate for obedience training, and learn how to help an- Photo by Brendan Meehan It wasn’t actually even my idea to get involved with service animals. -

Northeast Sector

Sites & Sectors Introduction 123 Northeast Sector 127 Site 12 133 Site 21 142 Site 25 145 Site A 155 Northwest Sector 167 Site 1 173 Site 2 183 Site 4 193 Site E 203 Southwest Sector 215 Site 6 221 Site 7 231 Site 9a/b 241 Site B 251 Site C 261 Site D 271 Southeast Sector 283 Site 10 289 Site 14 299 Site 16 309 Site 17a/b 319 Site 19 329 Introduction Of the 23 initial development sites on the St. George Campus, 14 remain. Opportunities for expansion, through balanced intensification, infill and strategic renewal exist within the University precinct on University land. On the remaining sites, approximately 277,000 gsm (214,000 net new gsm) of facilities, can be constructed within the existing and approved zoning envelopes. These and additional infill sites within the precinct can be rezoned to increase the capacity of the campus in the immediate term adding another 524,000 gsm (480,000 net new gsm) without requiring additional property. These opportunities will permit timely capital expansion to occur in the immediate and medium term, without adding the cost of land acquisition to future projects. The longer term must, however, include growth beyond the University boundaries. Collaboration and cooperation between the University community and municipal partners is essential to see success in these broader initiatives. Development sites have been grouped and reviewed by campus quadrant ‘sectors’. Within each sector, existing and new development sites are proposed. Each development site includes proposed zoning permissions which have resulted from a process of analysis including shadow and massing studies, circulation and servicing requirements, heritage building review and open space considerations. -

Making Space for Culture: Community Consultation Summaries

Making Space for Culture Community Consultation Summaries April 2014 Cover Photos courtesy (clockwise from top left) Harbourfront Centre, TIFF Bell Lightbox, Artscape, City of Toronto Museum Services Back Cover: Manifesto Festival; Photo courtesy of Manifesto Documentation Team Making Space for Culture: Overview BACKGROUND Making Space for Culture is a long-term planning project led 1. Develop awareness among citizens, staff, City Councillors by the City of Toronto, Cultural Services on the subject of cultural and potential partners and funders of the needs of cultural infrastructure city-wide. Funded by the Province of Ontario, the and community arts organizations, either resident or providing study builds on the first recommendation made in Creative Capital programming in their ward, for suitable, accessible facilities, Gains: An Action Plan for Toronto, a report endorsed by City equipment and other capital needs. Council in May 2011. The report recommends “that the City ensure 2. Assist with decision-making regarding infrastructure a supply of affordable, sustainable cultural space” for use by cultural investment in cultural assets. industries, not-for-profit organizations and community groups in the City of Toronto. While there has been considerable public and private 3. Disseminate knowledge regarding Section 37 as it relates investment in major cultural facilities within the city in the past to cultural facilities to City Councillors, City staff, cultural decade, the provision of accessible, sustainable space for small and organizations, and other interested parties. mid-size organizations is a key factor in ensuring a vibrant cultural 4. Develop greater shared knowledge and strengthen community. collaboration and partnerships across City divisions and agencies with real estate portfolios, as a by-product of the The overall objective of the Making Space for Culture project is to consultation process. -

3D Map1103.Pdf

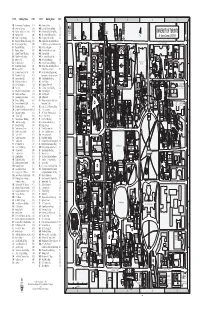

CODE Building Name GRID CODE Building Name GRID 1 2 3 4 5 AB Astronomy and Astrophysics (E5) LM Lash Miller Chemical Labs (D2) AD WR AD Enrolment Services (A2) LW Faculty of Law (B4) Institute of AH Alumni Hall, Muzzo Family (D5) M2 MARS 2 (F4) Child Study JH ST. GEORGE OI SK UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO 45 Walmer ROAD BEDFORD AN Annesley Hall (B4) MA Massey College (C2) Road BAY SPADINA ST. GEORGE N St. George Campus 2017-18 AP Anthropology Building (E2) MB Lassonde Mining Building (F3) ROAD SPADINA Tartu A A BA Bahen Ctr. for Info. Technology (E2) MC Mechanical Engineering Bldg (E3) BLOOR STREET WEST BC Birge-Carnegie Library (B4) ME 39 Queen's Park Cres. East (D4) BLOOR STREET WEST FE WO BF Bancroft Building (D1) MG Margaret Addison Hall (A4) CO MK BI Banting Institute (F4) MK Munk School of Global Affairs - Royal BL Claude T. Bissell Building (B2) at the Observatory (A2) VA Conservatory LI BN Clara Benson Building (C1) ML McLuhan Program (D5) WA of Music CS GO MG BR Brennan Hall (C5) MM Macdonald-Mowat House (D2) SULTAN STREET IR Royal Ontario BS St. Basil’s Church (C5) MO Morrison Hall (C2) SA Museum BT Isabel Bader Theatre (B4 MP McLennan Physical Labs (E2) VA K AN STREET S BW Burwash Hall (B4) MR McMurrich Building (E3) PAR FA IA MA K WW HO WASHINGTON AVENUE GE CA Campus Co-op Day Care (B1) MS Medical Sciences Building (E3) L . T . A T S CB Best Institute (F4) MU Munk School of Global Affairs - W EEN'S EEN'S GC CE Centre of Engineering Innovation at Trinity (C3) CHARLES STREET WEST QU & Entrepreneurship (E2) NB North Borden Building (E1) MUSEUM VP BC BT BW CG Canadiana Gallery (E3) NC New College (D1) S HURON STREET IS ’ B R B CH Convocation Hall (E3) NF Northrop Frye Hall (B4) IN E FH RJ H EJ SU P UB CM Student Commons (F2) NL C. -

Honor Societies 1

Honor Societies 1 Phi Sigma Tau serves as a means of awarding distinction to students HONOR SOCIETIES who have high scholarship and personal interest in philosophy, as well as popularizing interest in philosophy among the general collegiate population. Canisius College has chapters of a number of national and international honor societies. These societies have established specific Psi Chi is an international honor society in psychology and recognizes academic requirements for students who wish to join the society, and most students at both the undergraduate and graduate level. also have additional requirements that may include service, participation, Sigma Delta Pi is the national collegiate Hispanic honor society. recommendations, or academic standing guidelines. Membership is available to students who attain excellence in the study of the Honor Societies Open to Students in Any Major Spanish language and its cultures in Europe and Americas. Alpha Sigma Nu is the honor society of Jesuit institutions of higher Sigma Iota Rho is the International Studies honor society and encourages education, including all 28 Jesuit colleges and universities in the United a life-long devotion to a better understanding of the world we live in and States, Regis College of the University of Toronto, Campion College in to continuing support for and engagement in education, service, and Regina, Saskatchewan, and Sogang University in Seoul, South Korea. Juniors, occupational activities that reflect the mission of Sigma Iota Rho. seniors, and students in graduate and professional schools who rank in the top 15 percent of their classes may be considered for membership. The Sigma Tau Delta is an international English honor society that honors college’s chapter may nominate no more than four percent of the junior undergraduates, graduate students, and scholars in academia, as well as upon and senior classes for membership. -

2017-2018 Academic Catalog 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents

2017-2018 1 400 The Fenway Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.emmanuel.edu Arts and Sciences Office of Admissions 617-735-9715 617-735-9801 (fax) [email protected] Graduate and Professional Programs 617-735-9700 617-507-0434 (fax) [email protected] The information contained in this catalog is accurate as of August 2017. Emmanuel College reserves the right, however, to make changes at its discretion affecting poli cies, fees, curricula or other matters announced in this catalog. It is the policy of Emmanuel College not to discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation or the presence of any disability in the recruitment and employment of faculty and staff and the operation of any of its programs and activities, as specified by federal laws and regulations. Emmanuel College is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges, Inc. through its Commission on Institutions of Higher Education. Inquiries regarding the accreditation status by the New England Association should be directed to the administrative staff of the institution. Individuals may also contact: Commission on Institutions of Higher Education New England Association of Schools and Colleges 3 Burlington Woods Drive, Suite 100 Burlington, MA 018034514 7812710022 EMail: [email protected] 2017-2018 Academic Catalog 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents About Emmanuel College ..............5 Biostatistics .........................67 Business and Economics ............ 69 Economics ......................70 General Information -

Watch for Muggers

I Sex for sale i~1 neighbori~g communities PAGE 24 READERS CH01cE1 last Week • to Vote :J Community Newspaper Company www.allstonbnghtontab.com FRIDAY. FEBRUARY 27, 2004 Vol. 8. No. 29 48 Pages 3 Sections 75¢ End ofa peace.fit! day Cops on ·~ watch for muggers By Josh B. Wardrop .ILL'd \\ th .111 111L rca,t•d polict: p1l•,•.:11ce 111 .\11"1111 Bn ·ht111111L·1g.hhorho0<.k and puhliL F "''~trl'l ll.'" lll liil·ll" crime' -,preading. the (\\(1 tT1 1111 11a(, \\ .illled 111 C• llllll'l'llOll "11h a ,lnnt!, it Jan ua1'> con\ L' lliL'llLL' ' lPtc mbhL·ne' thn>u!!hout A B \L'L'lll (() ha\L' llll"llL'd tli1·1 1 allL'illtOll lO the' \(rL'Cl\. lkl\\L'L'I' I eh. l) I \.I J1,tnll 14 Polil'L' l°L''j)\llldL·d \l1 h1ur rl'p11rh 11l 1m1)..·~i11~' .11 gunpnilll 1hat thL') he lie' L' "l'l"L' perpetr.itvd h\ thl ,amc l\\(l 'uspL'L'h \\ .tlltL·d Ii ir al ka't It knm111L'IC1al nibhl'l'IL" 111 \ h ,111Lt: :h1: l'L'Ulllllm nl thc \e,1r. '\\l.'rL' lhl( .dh11lt1h•f\ p;hJ(l\L' )(°\ (ilL' \,llllL' (\\() lll'n · ,,11d I )1,ll"IL'l I I I 'olicl' ( '.ipt. \\ illia111 L' a1h. "hut ti L' de''- 1pt on 11.11L·h up. and lhL· ".t\ e 1lf 1 1l1Pll, l I'''•' 'l< ,• 111hht:11L'' ,1np1x.·d .il l hL· ,a111t· t1111e thL''L 111ug.g.111g~ iil· •an . -

3D Map20190723.Pdf

CODE Building Name GRID CODE Building Name GRID 1 2 3 4 5 AB Astronomy and Astrophysics (E2) MA Massey College (C2) AD WR AD Enrolment Services (A2) MB Lassonde Mining Building (F3) Institute of AH Alumni Hall, Muzzo Family (D5) MC Mechanical Engineering Bldg (E3) Child Study JH ST. GEORGE OI SK UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO 45 Walmer ROAD BEDFORD AN Annesley Hall (B4) ME 39 Queen's Park Cres. East (D4) Road BAY SPADINA ST. GEORGE N St. George Campus 2019-20 AP Anthropology Building (E2) MG Margaret Addison Hall (A4) ROAD SPADINA Tartu A A BA Bahen Ctr. for Info. Technology (E2) MK Munk School of Global Affairs & BLOOR STREET WEST BC Birge-Carnegie Library (B4) Public Policy at the Observatory (A2) BLOOR STREET WEST FE WO BF Bancroft Building (D1) ML McLuhan Program (D5) CO MK BI Banting Institute (F4) MM Macdonald-Mowat House (D2) Royal BL Claude T. Bissell Building (B2) MO Morrison Hall (C2) VA Conservatory LI BN Clara Benson Building (C1) MP McLennan Physical Labs (E2) WA of Music CS GO MG BR Brennan Hall (C5) MR McMurrich Building (E3) SULTAN STREET IR Royal Ontario BS St. Basil’s Church (C5) MS Medical Sciences Building (E3) Museum T REE K BT Isabel Bader Theatre (B4 MU Munk School of Global Affairs & VA T AN S S BW Burwash Hall (B4) Public Policy at Trinity (C3) PAR FA IA MA WW K WASHINGTON AVENUE GE CA Campus Co-op Day Care (B1) MY Myhal Centre of Engineering L . THO . A T S CG Canadiana Gallery (E3) Innovation & Entrepreneurship (E2) W EEN'S EEN'S GC CH Convocation Hall (E3) NB North Borden Building (E1) CHARLES STREET WEST QU CN 89 Chestnut Residence (F5) NC New College (D1) MUSEUM BW VP BC BT Charles St. -

Academic Calendar

2020-2021 Academic Calendar 2021-22 Wycliffe College at the University of Toronto Wycliffe College Academic Calendar 2021 - 22 1 2020-2021 All information corrects at the time of publication (June 2021) Subject to further changes and corrections. 5 Hoskin Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5S 1H7 Canada Telephone: (416) 946-3535 Facsimile: (416) 946-8309 Email: Admissions: [email protected] Registrar: [email protected] Front Desk: [email protected] Website: www.wycliffecollege.ca Federated with the University of Toronto Member College, Toronto School of Theology Accredited by the Commission on Accrediting of the Association of Theological Schools in the United States and Canada, and the following degree programs are approved: M.Div. M.T.S. D.Min. Th.M. Th.D. (closed to new applications) Ph.D. in Theological Studies M.A. in Theological Studies Approved for a Comprehensive Distance Education Program The Commission Contact information is: The Commission on Accrediting of the Association of Theological Schools in the United States and Canada 10 Summit Park Drive Pittsburgh, PA 15275 Telephone: (412) 788-6505 Fax: (412) 788-6510 Website: www.ats.edu Wycliffe College Academic Calendar 2021 - 22 2 2020-2021 Wycliffe College Academic Calendar 2021 - 22 3 2020-2021 PRINCIPAL’S MESSAGE Dear Fellow Learners, Most calendars are utilitarian documents. In Rome, they belonged to accountants who fashioned registers noting when accounts were due. But then, I imagine, some poor bookkeeper discovered that this would be a convenient place to record other important dates - like birthdays and anniversaries! Calendars have, of course, become useful aides-mémoires, and in the Wycliffe Calendar you will find a small section that contains important deadlines and notices for the coming academic year (though you are on your own for anniversaries!). -

Regis College Catalog

REGIS COLLEGE Denver, Colorado Catalog 1931 INDEX ON PAGE ONE Regis College Denver A College of Arts and Sciences A Boarding and Day College for Men Conducted by the Jesuit Fathers *£ Courses of Instruction Regis College maintains standard programs collegiate instruction leading to the degrees Bachelor of Arts Bachelor of Science Bachelor of Science in Commerce Bachelor of Philosophy Regis College conducts thorough courses in Teacher-Training Pre-Dentistry Pre-Engineering Pre-Law Pre-Medicine Regis College conducts Evening Courses ar Saturday Courses whenever a suitable numbi request them. NDEX INDEX k .B. Degree 31, 34 German 57 cademic Year 19 Grades 20 ccounting 42 Graduation Requirements.. 32 acknowledgments 88 Greek 58 dministration Officers 4 Historical Sketch 10 dmission, Methods of 28 History .- 59 dvanced Standing 29 Honors 23, 86 attendance 18 Journalism 51 ;.S. Degree 31, 35 Laboratories 14 J.S. in Commerce Latin 61 Degree 31, 36 Library 14 Request, Form of 16 Location 12 Jiology 14, 43 Mathematics 63 Soard of Managers 4 Merchandising 65 buildings - 13 Needs of the College 15 Calendar 3 Orientation 66 ampus Residence* 17 Ph.B. Degree 31, 37 :hemistry 14, 44 Philosophy 66 Tlass Hours 19 Physics 14, 69 lassification of Students.. 30 Pre-Dentistry, Minimum.... 40 College Organizations 75 Pre-Engineering, ommencement 83 Minimum 41 Commerce and Finance..31, 36 Pre-Law, Minimum 41 ourses of Instruction.... 12, 42 Pre-Medicine, Minimum.... 40 Degree Requirements.. ..31, 38 Prizes, Medals 16, 22, 84 Degrees Conferred 83 Public Lectures 12 Departments of Instruction 42 Public Speaking 70 Discipline 17 Reference Study 39 Drawing, Engineering 50 Regis High School 87 Economics 46 Registration 26 Education 48 Religion 11, 71 Electives 27, 38, 39 Reports 20 Employment 25 Research 39 Endowment 15 Saturday Courses 19, 81 Engineering Drawing 50 Scholarships 16, 21, 25 English 51 Seismic Observatory 14 Enrollment 78 Spanish 73 Entrance Requirements. -

Graduate Conjoint Degree Handbook 2018-19 1

2018-19 September 2018 Toronto School of Theology Graduate Centre for Theological Studies 47 Queen’s Park Crescent East, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2C3 www.tst.edu [email protected] 416-978-4050 The Toronto School of Theology The Toronto School of Theology (TST) is an ecumenical federation of seven member colleges. The following colleges participate in TST’s graduate programs: Emmanuel College (United Church of Canada), Knox College (Presbyterian Church in Canada), Regis College (Roman Catholic, Society of Jesus), the Faculty of Theology of the University of St. Michael's College (Roman Catholic, Basilian Fathers), the Faculty of Divinity of the University of Trinity College (Anglican) and Wycliffe College (Anglican). The colleges do not establish independent program requirements for the graduate degree programs. They support their graduate degree communities in various ways, such as teaching courses in the graduate programs; providing supervision of graduate students; participating in TST’s governance structures; and providing financial aid to students. Every graduate (advanced degree) student must be accepted for admission into one of the six participating theological institutions ("colleges"). Each conjoint degree is conferred under the authority of statutes and regulations of the province of Ontario, by both the student’s college and the UofT. Mission Statement The TST consortium is strongly committed to: critical reflection and scholarly research on matters of Christian faith, practice and ministry; excellence in theological education