The Rehabilitation of the Col. Robert Means Mansion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocm01251790-1863.Pdf (10.24Mb)

u ^- ^ " ±i t I c Hon. JONATHAN E. FIELD, President. 1. —George Dwight. IJ. — K. M. Mason. 1. — Francis Briwiej'. ll.-S. .1. Beal. 2.— George A. Shaw. .12 — Israel W. Andrews. 2.—Thomas Wright. 12.-J. C. Allen. 3. — W. F. Johnson. i'i. — Mellen Chamberlain 3.—H. P. Wakefield. 13.—Nathan Crocker. i.—J. E. Crane. J 4.—Thomas Rice, .Ir. 4.—G. H. Gilbert. 14.—F. M. Johnson. 5.—J. H. Mitchell. 15.—William L. Slade. 5. —Hartley Williams. 15—H. M. Richards. 6.—J. C. Tucker. 16. —Asher Joslin. 6.—M. B. Whitney. 16.—Hosea Crane. " 7. —Benjamin Dean. 17.— Albert Nichols. 7.—E. O. Haven. 17.—Otis Gary. 8.—William D. Swan. 18.—Peter Harvey. 8.—William R. Hill. 18.—George Whitney. 9.—.]. I. Baker. 19.—Hen^^' Carter. 9.—R. H. Libby. 19.—Robert Crawford. ]0.—E. F. Jeiiki*. 10.-—Joseph Breck. 20. —Samuel A. Brown. .JOHN MORIS?5KV, Sevii^aiU-ut-Anns. S. N. GIFFORU, aerk. Wigatorn gaHei-y ^ P=l F ISSu/faT-fii Lit Coiranoittoralllj of llitss3t|ttsttts. MANUAL FOR THE USE OF THE G-ENERAL COURT: CONTAINING THE RULES AND ORDERS OF THE TWO BRANCHES, TOGETHER WITH THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH, AND THAT OF THE UNITED STATES, A LIST OF THE EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE, AND JUDICIAL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT, STATE INSTITUTIONS AND THEIR OFFICERS, COUNTY OFFICERS, AND OTHER STATISTICAL INFORMATION. Prepared, pursuant to Orders of the Legislature, BY S. N. GIFFORD and WM. S. ROBINSON. BOSTON: \yRIGHT & POTTER, STATE PRINTERS, No. 4 Spring Lane. 1863. CTommonbtaltfj of iBnssacf)useits. -

Ranking America's First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary Moves from 2 to 5 ; Jackie

For Immediate Release: Monday, September 29, 2003 Ranking America’s First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 nd Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary moves from 2 nd to 5 th ; Jackie Kennedy from 7 th th to 4 Mary Todd Lincoln Up From Usual Last Place Loudonville, NY - After the scrutiny of three expert opinion surveys over twenty years, Eleanor Roosevelt is still ranked first among all other women who have served as America’s First Ladies, according to a recent expert opinion poll conducted by the Siena (College) Research Institute (SRI). In other news, Mary Todd Lincoln (36 th ) has been bumped up from last place by Jane Pierce (38 th ) and Florence Harding (37 th ). The Siena Research Institute survey, conducted at approximate ten year intervals, asks history professors at America’s colleges and universities to rank each woman who has been a First Lady, on a scale of 1-5, five being excellent, in ten separate categories: *Background *Integrity *Intelligence *Courage *Value to the *Leadership *Being her own *Public image country woman *Accomplishments *Value to the President “It’s a tracking study,” explains Dr. Douglas Lonnstrom, Siena College professor of statistics and co-director of the First Ladies study with Thomas Kelly, Siena professor-emeritus of American studies. “This is our third run, and we can chart change over time.” Siena Research Institute is well known for its Survey of American Presidents, begun in 1982 during the Reagan Administration and continued during the terms of presidents George H. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush (http://www.siena.edu/sri/results/02AugPresidentsSurvey.htm ). -

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

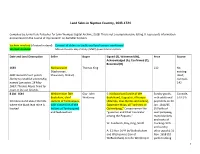

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

Activity Book Navigating the Bill Process

Activity Book Navigating the Bill Process 2 Know Your Presidents Can you find all these words in the crossword above? ADAMS GARFIELD LINCOLN ROOSEVELT GRANT ARTHUR MADISON TAFT HARDING BUCHANAN MCKINLEY TAYLOR BUSH HARRISON MONROE TRUMAN CLEVELAND HAYES NIXON TRUMP HOOVER CLINTON OBAMA TYLER COOLIDGE JACKSON PIERCE VANBUREN EISENHOWER JEFFERSON POLK WASHINGTON JOHNSON FILLMORE REAGAN WILSON FORD KENNEDY Bonus: Several Presidents shared the same last name – how many do you know? names) five (Hint: 3 Know Your Civics Can you find all these words in the crossword above? AMERICA GOVERNOR POLLING BALLOT HOUSE PRESIDENT BILL JUDICIAL PUBLIC HEARING CANDIDATE LAW PUBLIC POLICY CAPITOL LEGISLATURE REPRESENTATIVE CIVICS MAYOR SENATE COMMITTEE NATION SENATOR CONGRESS NONPARTISAN UNITED STATES COUNTRY POLITICAL TESTIMONY ELECTION POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE VOTE GOVERNMENT POLITICAL PARTY WHITE HOUSE 4 U.S. Citizenship Practice Test Could you pass the U.S. Citizenship test? Take these practice questions from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to find out! 1. Name the US war between the North and the South. a. World War I b. The Civil War c. The War of 1812 d. The Revolutionary War 2. What is one thing Benjamin Franklin is famous for? a. U.S. diplomat b. Youngest member of the Constitutional Convention c. Third President of the United States d. Inventor of the Airplane 3. Who did the United States fight in World War II? a. The Soviet Union, Germany, and Italy b. Austria-Hungary, Japan, and Germany c. Japan, China, and Vietnam d. Japan, Germany, and Italy 4. Who signs bills to become laws? a. The Secretary of State b. -

The Shays Rebellion a Political Aftermath

1911.] The Shays Rebellion. 67 THE SHAYS REBELLION A POLITICAL AFTERMATH. BY ANDREW MACPARLAND DAVIS. At the October meeting of this Society in 1902, Mr. John Noble read a paper entitled "A few notes on the Shays rebellion." Mr. Charles Francis Adams, who was present, expressed the hope that a special research nught be made as to the causes of the then existing discontent.^ At the May meeting of the Massachusetts Historical Society, in 1905^ Mr. Adams, in commenting on a publication entitled "Some features of Shays's rebeUion " by Jonathan Smith of Clinton, Massachusetts, said that in the written accounts of the rebellion, "no attempt has been made to go below the surface, and show what were the causes of the great unrest which then prevailed. " In selecting my subject for this paper, I had in mind the suggestions of Mr. Adams, but it will be seen by my title, that I have not undertaken to cover exactly the field to which he referred. There seems to me to be abundant explanation for the dis- content of the populace at that time, in the fact that a large pai-t of the community was forced to resort to barter through lack of a circulating medium. Add to that the necessarily burdensome nature of the war taxes, and you have a condition of affah-s which could not have been patiently borne by any but a saintly or a very intelligent community. My thesis is not therefore to show why there was unrest, but why there was violence. ^Prooeedinga American Antiquarian Society. -

Classes Without Quizzes-Edited

MARTHA WAS H INGTON A BIGA IL A DA M S MARTHA JEFFERSON DOLLEY MADISON S S ELISZ WABETHO MONROE LSO UISA A D A M S RACHEL JAC KS O N H ANNA H VA N B UREN A N NA H A RRIS O N featuring L ETITI A T YLER JULIA T YLE R S A R AH P OLK MARG A RET TAY L OR AnBIitGaAIL FcILBL MrOREide J A N E PIER C E 11 12 H A RRIET L ANE MAR YJoin T ODDfor a discussion L INC OonL N E LIZ A J OHN S O N JULIA GRANT L U C Y H AY E S LUC RETIA GARFIELD ELLEN ARTHUR FRANCES CLEVELAND CAROLINE HARRISON 10 IDA MCKINLEY EDITH ROOSEVELT HELEN TAFT ELLEN WILSON photographers, presidential advisers, and social secretaries to tell the stories through “Legacies of America’s E DITH WILSON F LORENCE H ARDING GRACE COOLIDGE First Ladies conferences LOU HOOVER ELEANOR ROOSEVELT ELIZABETH “BESS”TRUMAN in American politics and MAMIE EISENHOWER JACQUELINE KENNEDY CLAUDIA “LADY for their support of this fascinating series.” history. No place else has the crucial role of presidential BIRD” JOHNSON PAT RICIA “PAT” N IXON E LIZABET H “ BETTY wives been so thoroughly and FORD ROSALYN C ARTER NANCY REAGAN BARBAR A BUSH entertainingly presented.” —Cokie Roberts, political H ILLARY R O DHAM C L INTON L AURA BUSH MICHELLE OBAMA “I cannot imagine a better way to promote understanding and interest in the experiences of commentator and author of Saturday, October 18 at 2pm MARTHA WASHINGTON ABIGAIL ADAMS MARTHA JEFFERSON Founding Mothers: The Women Ward Building, Room 5 Who Raised Our Nation and —Doris Kearns Goodwin, presidential historian DOLLEY MADISON E LIZABETH MONROE LOUISA ADAMS Ladies of Liberty: The Women Who Shaped Our Nation About Anita McBride Anita B. -

Ocm01251790-1865.Pdf (10.56Mb)

11 if (^ Hon. JONATHAN Ii'IBIiD, President. RIGHT. - - Blaisdell. - Wentworth. 11 Josiah C — Jacob H. Loud. 11. _ William L. Keed. Tappan -Martin Griffin. 12.- - Francis A. Hobart. — E. B. Stoddard. 12. — John S. Eldridge. - 2d. - Pitman. 1.3.- James Easton, — George Hej'wood. 13. — William VV.CIapp, Jr. Robert C. Codman. 14.- - Albert C Parsons. — Darwin E. 'Ware. 14. — Hiram A. Stevens. -Charles R - Kneil. - Barstow. 15.- Thomas — Francis Childs. 15 — Henr)' Alexander, Jr- Henry 16.- - Francis E. Parker. — Freeman Cobb. 16.— Paul A. Chadbourne. - George Frost. - Southwick. - Samuel M. Worcester. 17. Moses D. — Charles Adams, Jr. 17. — John Hill. 18. -Abiiah M. Ide. 18. — Eben A. Andrews. -Alden Leiand. — Emerson Johnson. Merriam. Pond. -Levi Stockbridge. -Joel — George Foster. 19. — Joseph A. Hurd. - Solomon C. Wells, 20. -Yorick G. — Miio Hildreth. S. N. GIFFORD, Clerk. JOHN MORISSEY. Serffeant-nt-Arms. Cflininontofaltl of llassadprfts. MANUAL FOR THE USE OP THE GENERAL COURT CONTAlN'mG THE RULES AND ORDERS OF THE TWO BRANCHES, TOGETHER WITH THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH, AND THAT OF THE UNITED STATES, A LIST OF THE EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE, AND JUDICIAL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT, STATE INSTITUTIONS AND THEIR OFFICERS, COUNTY OFFICERS, AND OTHER STATISTICAL INFORMATION. i'C^c Prepared, pursuant to Orders of the Legislature, BY S. N. GIFFORD and WM. S. ROBINSON. BOSTON: \7RIGHT & POTTER, STATE PRINTERS, No. 4 Spring Lane. 186 5. Ccmmotttoealtfj of iHassncfjugetts. In Senate, January 10, 1865. Ordered, That the Clerks of the two branches cause to be printed and bound m suitable form two thousand copies of the Rules and Orders of the two branches, with lists of the several Standing and Special Committees, together with such other matter as has been prepared, in pursuance to an Order of the last legisla- ture. -

European Journal of American Studies, 10-1 | 2015 “First Lady but Second Fiddle” Or the Rise and Rejection of the Political Cou

European journal of American studies 10-1 | 2015 Special Issue: Women in the USA “First Lady But Second Fiddle” or the rise and rejection of the political couple in the White House: 1933-today. Pierre-Marie Loizeau Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/10525 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.10525 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Pierre-Marie Loizeau, ““First Lady But Second Fiddle” or the rise and rejection of the political couple in the White House: 1933-today.”, European journal of American studies [Online], 10-1 | 2015, document 1.5, Online since 26 March 2015, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/ 10525 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.10525 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License “First Lady But Second Fiddle” or the rise and rejection of the political cou... 1 “First Lady But Second Fiddle” or the rise and rejection of the political couple in the White House: 1933- today. Pierre-Marie Loizeau 1 One of the striking points of the presidential function lies in its being exclusively male. In the country of democracy and freedom par excellence, half of the population, as it were, has been excluded from electoral rolls. In reality, female representation has been one of the great weaknesses of the American government, not to mention the whole body politic in the history of the Republic Despite undeniable progress, especially in the last forty years, female leaders remain a minority in the country. The three women who have held the post of state secretaries (Madeleine Albright, Condoleezza Rice, and Hillary Clinton) in the last three administrations and the former House Speaker (Nancy Pelosi) remain exceptions to the rule. -

American First Ladies

AMERICAN FIRST LADIES Their Lives and Their Legacy edited by LEWIS L. GOULD GARLAND PUBLISHING, INC. NewYork S^London 1996 Contents Acknowledgments Introduction:The First Lady as Symbol and Institution Lewis L. Gould MarthaWashington 2 Patricia Brady Abigail Adams 16 Phyllis Lee Levin Dollej Madison 45 Holly Cowan Shulman Elizabeth Monroe 69 Julie K. Fix Louisa Adams 80 Lynn Hudson Parsons CONTENTS Anna Harrison 98 Nancy Beck Young LetitiaTyler 109 Melba Porter Hay Julia Tyler 111 Melba Porter Hay Sarah Polk 130 Jayne Crumpler DeFiore Margaret Taylor 145 Thomas H. Appleton Jr. Abigail Eillmore 154 Kristin Hoganson Jane Pierce 166 Debbie Mauldin Cottrell Mary Todd Lincoln 174 Jean H. Baker Eliza Johnson 191 Nancy Beck Young CONTENTS Julia Grant 202 John Y. Simon Lucy Webb Hayes 216 Olive Hoogenboom Lucretia Garfield 230 Allan Peskin Frances Folsom Cleveland 243 Sue Severn Caroline Scott Harrison 260 Charles W. Calhoun Ida Saxton McKinley 211 JohnJLeJfler Edith Kermit Roosevelt 294 Stacy A. Cordery Helen Herr on Toft 321 Stacy A. Cordery EllenAxsonWilson 340 Shelley Sallee CONTENTS Edith BollingWilson 355 Lewis L. Gould Florence Kling Harding 368 Carl Sferrazza Anthony Grace Goodhue Coolidge 384 Kiistie Miller Lou Henry Hoover 409 Debbie Mauldin Cottrell J Eleanor Roosevelt 422 Allida M. Black Bess Truman 449 Maurine H. Beasley Mamie Eisenhower 463 Martin M. Teasley Jacqueline Kennedy 416 Betty Boyd Caroli Lady Bird Johnson 496 Lewis L. Gould CONTENTS Patricia Nixon 520 Carl SJerrazza Anthony Betty Ford 536 John Pope Rosalynn Carter 556 Kathy B. Smith Nancy Reagan 583 James G. Benzejr. Barbara Bush 608 Myra Gutin Hillary Rodham Clinton 630 ^ Lewis L. -

Compliments of Hamilton and Sargent: a Story of Mystery and Tragedy and the Closing of the American Frontier

Annual Report Vol. 42 (2019) Compliments of Hamilton and Sargent: a story of mystery and tragedy and the closing of the American frontier Maura Jane Farrelly American Studies Program, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA [email protected] In December of 1882, the great American naturalist “I have been credibly informed...that 4,000 elk were George Grinnell published an editorial in his maga- killed by skin hunters in one winter,” Sheridan wrote zine, Forest and Stream, that called for federal offi- to Interior Secretary Henry Moore Teller in the ex- cials to move Yellowstone National Park’s boundary cerpt featured in Forest and Stream, “and that even south by about ten miles. Grinnell wanted the border last winter, in and around the edges of the park, there to go all the way to the 44th parallel, an area that today were as many as two thousand of these grand an- includes the John D. Rockefeller Memorial Parkway, imals killed.” The decorated Civil War veteran and connecting Yellowstone to its much smaller neighbor, famed Indian-killer wanted Yellowstone to be a pro- Grand Teton National Park. The geyser-riddled land- tective “reservation” for the wildlife found in the Amer- scape that Americans once called “The New Won- ican West. The creatures’ migration patterns, how- derland” had been designated a national park a little ever, made it such that the park would have to be more than a decade earlier by an act of Congress. bigger in order for it to serve that function. “This year Yellowstone was America’s first national park, and its I noticed. -

The Rhetorical Persona of Michelle Obama and the "Let's Move" Campaign

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2012 Mother Knows Best: The Rhetorical Persona of Michelle Obama and the "Let's Move" campaign Monika Bertaki University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Politics Commons, Rhetoric Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Repository Citation Bertaki, Monika, "Mother Knows Best: The Rhetorical Persona of Michelle Obama and the "Let's Move" campaign" (2012). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1541. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/4332521 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOTHER KNOWS BEST: THE RHETORICAL PERSONA OF MICHELLE OBAMA AND THE “LET’S MOVE” CAMPAIGN By Monika Bertaki Bachelor of Arts in Communication Studies University of Nevada, -

Abbot, J. Genealogy Abbot, J.G. Abbot, Nehemiah Abbott, A. A. Abbott

Miscellaneous Manuscripts Collection At the American Antiquarian Society BIB 442326 Abbot, J. Genealogy Abbot, J.G. Abbot, Nehemiah Abbott, A. A. Abbott, Charles Abbott, Jacob Abbott, Lyman Ab-y, Father Father Ab-y's Will, copy of poem Abington, MA Abington, MA (First Parish) Acton, MA Adamson, William William S. Pelletreau Addington, Isaac To Stephen Sewall Adler, Elmer A. Agassiz, Alexander Agassiz, Elizabeth C. Agassiz, Jean-Pierre Agassiz, Louis Friday Club material Ager Family Aikin, Arthur Aird, James Purchase of land in Florida Aitken, Robert Abbey, Charles E. Abbott, John S. C. Alaska List of Alaska newspapers, E.W. Allen Albee Family Albion, J. F. Alcott, A. Bronson Alcott, E. S. Alcott, Louisa M. Alcott, William Andrus Alden, H. M. Aldrich, Anne Reeve Aldrich, Charles F. Aldrich, P. Emory Alexander, Caleb Alexander, Thomas Alger, Jr. Horatio Alger, William R. Allee, J. F. Allen, Anna Allen, E. M. Allen, Ethan Allen, George American Anti-Slavery Society Commission Allen, Horace Allen, Ira Allen, James Allen, John Allen, Katherine Allen, Raymond C. Allen, Samuel, Jr. Allen, Silas Allen, Thaddeus Allen, Thomas Allen, William Allyn, John Almanac Alsop, Richard Alrord, C. A. Alden, Timothy Allen, Joseph Allen, Samuel America, Primitive Inhabitants American Bible Union American Historical Society American Republican Association American School Agent American Unitarian Association Ames, Azel, Jr. Ames, Harriet A. Ames, John G. Ames, Oliver Ames, R. P. M. Ames, Samuel Amhert, Jeffrey Ammidown, Holmes Amory, Frederic Amory, Jonathan Amory, Thomas C. Amory, Thomas C., Jr. Amory, W. Amsden, Ebenezer Amsden, Robards Anderson, Alexander Anderson, Rufus Andover Theological Seminary Andrew, John A.