The Shays Rebellion a Political Aftermath

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocm01251790-1863.Pdf (10.24Mb)

u ^- ^ " ±i t I c Hon. JONATHAN E. FIELD, President. 1. —George Dwight. IJ. — K. M. Mason. 1. — Francis Briwiej'. ll.-S. .1. Beal. 2.— George A. Shaw. .12 — Israel W. Andrews. 2.—Thomas Wright. 12.-J. C. Allen. 3. — W. F. Johnson. i'i. — Mellen Chamberlain 3.—H. P. Wakefield. 13.—Nathan Crocker. i.—J. E. Crane. J 4.—Thomas Rice, .Ir. 4.—G. H. Gilbert. 14.—F. M. Johnson. 5.—J. H. Mitchell. 15.—William L. Slade. 5. —Hartley Williams. 15—H. M. Richards. 6.—J. C. Tucker. 16. —Asher Joslin. 6.—M. B. Whitney. 16.—Hosea Crane. " 7. —Benjamin Dean. 17.— Albert Nichols. 7.—E. O. Haven. 17.—Otis Gary. 8.—William D. Swan. 18.—Peter Harvey. 8.—William R. Hill. 18.—George Whitney. 9.—.]. I. Baker. 19.—Hen^^' Carter. 9.—R. H. Libby. 19.—Robert Crawford. ]0.—E. F. Jeiiki*. 10.-—Joseph Breck. 20. —Samuel A. Brown. .JOHN MORIS?5KV, Sevii^aiU-ut-Anns. S. N. GIFFORU, aerk. Wigatorn gaHei-y ^ P=l F ISSu/faT-fii Lit Coiranoittoralllj of llitss3t|ttsttts. MANUAL FOR THE USE OF THE G-ENERAL COURT: CONTAINING THE RULES AND ORDERS OF THE TWO BRANCHES, TOGETHER WITH THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH, AND THAT OF THE UNITED STATES, A LIST OF THE EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE, AND JUDICIAL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT, STATE INSTITUTIONS AND THEIR OFFICERS, COUNTY OFFICERS, AND OTHER STATISTICAL INFORMATION. Prepared, pursuant to Orders of the Legislature, BY S. N. GIFFORD and WM. S. ROBINSON. BOSTON: \yRIGHT & POTTER, STATE PRINTERS, No. 4 Spring Lane. 1863. CTommonbtaltfj of iBnssacf)useits. -

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

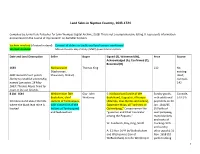

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

Ocm01251790-1865.Pdf (10.56Mb)

11 if (^ Hon. JONATHAN Ii'IBIiD, President. RIGHT. - - Blaisdell. - Wentworth. 11 Josiah C — Jacob H. Loud. 11. _ William L. Keed. Tappan -Martin Griffin. 12.- - Francis A. Hobart. — E. B. Stoddard. 12. — John S. Eldridge. - 2d. - Pitman. 1.3.- James Easton, — George Hej'wood. 13. — William VV.CIapp, Jr. Robert C. Codman. 14.- - Albert C Parsons. — Darwin E. 'Ware. 14. — Hiram A. Stevens. -Charles R - Kneil. - Barstow. 15.- Thomas — Francis Childs. 15 — Henr)' Alexander, Jr- Henry 16.- - Francis E. Parker. — Freeman Cobb. 16.— Paul A. Chadbourne. - George Frost. - Southwick. - Samuel M. Worcester. 17. Moses D. — Charles Adams, Jr. 17. — John Hill. 18. -Abiiah M. Ide. 18. — Eben A. Andrews. -Alden Leiand. — Emerson Johnson. Merriam. Pond. -Levi Stockbridge. -Joel — George Foster. 19. — Joseph A. Hurd. - Solomon C. Wells, 20. -Yorick G. — Miio Hildreth. S. N. GIFFORD, Clerk. JOHN MORISSEY. Serffeant-nt-Arms. Cflininontofaltl of llassadprfts. MANUAL FOR THE USE OP THE GENERAL COURT CONTAlN'mG THE RULES AND ORDERS OF THE TWO BRANCHES, TOGETHER WITH THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH, AND THAT OF THE UNITED STATES, A LIST OF THE EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE, AND JUDICIAL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT, STATE INSTITUTIONS AND THEIR OFFICERS, COUNTY OFFICERS, AND OTHER STATISTICAL INFORMATION. i'C^c Prepared, pursuant to Orders of the Legislature, BY S. N. GIFFORD and WM. S. ROBINSON. BOSTON: \7RIGHT & POTTER, STATE PRINTERS, No. 4 Spring Lane. 186 5. Ccmmotttoealtfj of iHassncfjugetts. In Senate, January 10, 1865. Ordered, That the Clerks of the two branches cause to be printed and bound m suitable form two thousand copies of the Rules and Orders of the two branches, with lists of the several Standing and Special Committees, together with such other matter as has been prepared, in pursuance to an Order of the last legisla- ture. -

Compliments of Hamilton and Sargent: a Story of Mystery and Tragedy and the Closing of the American Frontier

Annual Report Vol. 42 (2019) Compliments of Hamilton and Sargent: a story of mystery and tragedy and the closing of the American frontier Maura Jane Farrelly American Studies Program, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA [email protected] In December of 1882, the great American naturalist “I have been credibly informed...that 4,000 elk were George Grinnell published an editorial in his maga- killed by skin hunters in one winter,” Sheridan wrote zine, Forest and Stream, that called for federal offi- to Interior Secretary Henry Moore Teller in the ex- cials to move Yellowstone National Park’s boundary cerpt featured in Forest and Stream, “and that even south by about ten miles. Grinnell wanted the border last winter, in and around the edges of the park, there to go all the way to the 44th parallel, an area that today were as many as two thousand of these grand an- includes the John D. Rockefeller Memorial Parkway, imals killed.” The decorated Civil War veteran and connecting Yellowstone to its much smaller neighbor, famed Indian-killer wanted Yellowstone to be a pro- Grand Teton National Park. The geyser-riddled land- tective “reservation” for the wildlife found in the Amer- scape that Americans once called “The New Won- ican West. The creatures’ migration patterns, how- derland” had been designated a national park a little ever, made it such that the park would have to be more than a decade earlier by an act of Congress. bigger in order for it to serve that function. “This year Yellowstone was America’s first national park, and its I noticed. -

Abbot, J. Genealogy Abbot, J.G. Abbot, Nehemiah Abbott, A. A. Abbott

Miscellaneous Manuscripts Collection At the American Antiquarian Society BIB 442326 Abbot, J. Genealogy Abbot, J.G. Abbot, Nehemiah Abbott, A. A. Abbott, Charles Abbott, Jacob Abbott, Lyman Ab-y, Father Father Ab-y's Will, copy of poem Abington, MA Abington, MA (First Parish) Acton, MA Adamson, William William S. Pelletreau Addington, Isaac To Stephen Sewall Adler, Elmer A. Agassiz, Alexander Agassiz, Elizabeth C. Agassiz, Jean-Pierre Agassiz, Louis Friday Club material Ager Family Aikin, Arthur Aird, James Purchase of land in Florida Aitken, Robert Abbey, Charles E. Abbott, John S. C. Alaska List of Alaska newspapers, E.W. Allen Albee Family Albion, J. F. Alcott, A. Bronson Alcott, E. S. Alcott, Louisa M. Alcott, William Andrus Alden, H. M. Aldrich, Anne Reeve Aldrich, Charles F. Aldrich, P. Emory Alexander, Caleb Alexander, Thomas Alger, Jr. Horatio Alger, William R. Allee, J. F. Allen, Anna Allen, E. M. Allen, Ethan Allen, George American Anti-Slavery Society Commission Allen, Horace Allen, Ira Allen, James Allen, John Allen, Katherine Allen, Raymond C. Allen, Samuel, Jr. Allen, Silas Allen, Thaddeus Allen, Thomas Allen, William Allyn, John Almanac Alsop, Richard Alrord, C. A. Alden, Timothy Allen, Joseph Allen, Samuel America, Primitive Inhabitants American Bible Union American Historical Society American Republican Association American School Agent American Unitarian Association Ames, Azel, Jr. Ames, Harriet A. Ames, John G. Ames, Oliver Ames, R. P. M. Ames, Samuel Amhert, Jeffrey Ammidown, Holmes Amory, Frederic Amory, Jonathan Amory, Thomas C. Amory, Thomas C., Jr. Amory, W. Amsden, Ebenezer Amsden, Robards Anderson, Alexander Anderson, Rufus Andover Theological Seminary Andrew, John A. -

The Dudley Genealogies and Family Records

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com BOOK DOES 1WT ^\ t DUDLEY GENEALOGIES. THE DUDLEY GENEALOGIES AND FAMILY RECORDS. Arms borne by the Hon. Thomas Dudley, first Dep. Gov. and second Got. of Mass. Bay. BY DEAN DUDLEY. " Children's children arc the crown of old men ; And the glory of children are their fathers." .l^nftRTy" ^. State Historical So-: OF WISCONSIN,, BOSTON: 1876 „ PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR 1848. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1843, by Dean Dudlet, In the Clerk's office of the District Court for the District of Massachusetts. White & Potter, Printers, Corner Spring Lane and Devonshire street, Boston. as PREFACE. The Work, ^ Here presented, is intended as an introduction to a large • biographical account of the Dudley family, which I have long been collecting, and design to publish on my return from Eu rope, whither, I am about to proceed for the purpose of extend ing my researches further, than is practicable in this country. It seemed expedient to publish this collection thus early, in order, that an opportunity might be offered for the cor rection of unavoidable errors and the addition of such re cords, as might be found wanting in the genealogies. And, therefore, it is earnestly desired, that those, possessing addi tional records or corrections of errors, will forward them to me, as soon as possible ; and all appropriate biographical sketches will, also, be received with much gratitude. -

The Rehabilitation of the Col. Robert Means Mansion

The Rehabilitation of the Col. Robert Means Mansion Amherst, New Hampshire Bill Veillette For more information on the Col. Robert Means man- sion and its occupants, please contact me at: Bill Veillette 1 Pierce Lane Amherst, NH 03031 (603) 673-4856 [email protected]### © William P. Veillette, Amherst, N.H., 2009. Front cover image: Postcard of Col. Robert Means mansion. Hand colored, standard size, divided back; Boston: NEN, printed in France, c. 1910. Rear cover image: Eighteenth-century copper button and doll’s dress found in walls of Col. Robert Means house, Amherst, N.H. classical form. And, where it has seen alterations, al- The Rehabilitation of the most all of the evidence is still there to be able to de- Col. Robert Means Mansion, termine its original shape and features and how they have changed over time. Amherst, New Hampshire The house has dodged a few bullets, however. The 1 By Bill Veillette first was in 1788 when Michael Keef, a struggling yeoman, unfairly accused Robert Means, by now a wealthy merchant, of “grinding the face of the poor.” The Col. Robert Means “mansion house” (1785) is He threatened Means with “trouble.”4 Keef was later located in Amherst, New Hampshire, directly off the convicted of arson, which may have been the trouble southeast corner of what was known as “The Plain,” he had in mind. Next, the roof of the house caught fire where livestock used to graze and the militia once during town meeting in 1797. Because it was a stone’s drilled (1.1). Thirty-two-year-old Robert Means, a throw away from the meetinghouse, the mansion “was budding merchant, acquired the initial quarter acre of saved by there being plenty of help nearby.”5 There the property in 1774 “with the Shop & barn thereon was also the Great Fire of 1863 when Means’s adja- built by Me [Paul Dudley Sargent].”2 The “Shop,” cent store and three neighboring buildings on The which presumably became Robert Means’s store, Plain burned in the middle of the night. -

James Bowdoin: Patriot and Man of the Enlightenment

N COLLEGE M 1 ne Bowdoin College Library [Digitized by tlie Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/jamesbowdoinpatrOObowd 52. James BowdoinU^ Version B, ca. i 791, by Christian GuUager Frontisfiece JAMES BOWDOIN Patriot and Man of the Enlightenment By Professor Gordon E. Kershaw EDITED BY MARTHA DEAN CATALOGUE By R. Peter Mooz EDITED BY LYNN C. YANOK An exhibition held at the BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART Brunswick, Maine May 28 through September 12, 1976 © Copyright 1976 by The President and Trustees of Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Maine Front cover illustration: Number 16, James Bozvdoin II, by Robert Feke, 1748, Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Back cover illustrations: Number 48, Silhouette of James Bowdoin II, by an Unknown Artist, courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society; Number 47, signature of James Bowdoin II, from Autografh Letter, Boston, 1788, per- mission of Dr. and Mrs. R. Peter Mooz. This exhibition and catalogue were organized with the aid of grants from the Maine State American Revolution Bicentennial Commission and The First National Bank of Boston. Tyfesetting by The AntJioensen Press, Portland, Maine Printed by Salina Press, Inc., East Syracuse, Nezv York Contents List of Illustrations iv Foreword and Acknowledgments, r. peter mooz vii Chronology xi JAMES BOWDOIN: Patriot and Man of The Enlightenment, gordon e. kershaw i Notes 90 Catalogue, r. peter mooz 97 Bibliography 108 Plates III List of Illustrations Except as noted, the illustrations appear following the text and are numbered in the order as shown in the exhibition. o. 1. Sames Bozvdoi/i /, ca. 1725, by an Unknown Artist 2. -

Calculated for the Use of the State Of

317.3M3! [4 A MPHIVCS : /( V THE MASSACHUSETTS REGISTER, AND For the Year of our Lord 18 2 5, Being the first after Bissextile, or Leap Year, and Forty- ninth o( American Independence, <r CONTAINING Civile Judicial, Ecclesiastical and Military Lists in Associations, and Corporate Institutions for literary, agricultural, and charitable Purposes. A List of Post-Towns in Massachusetts, with the Na?nes of the Post-Masters. CITY OFFICERS IN BOSTON. ALSO, i Catalogues of the Officers of the GENERAL GOVERNMENT, With its several Departments and Establishments Times of the Sittings of the several Courts; Governors hi each State ; And a -V, Variety of other interesting Articles. BOSSOJTJ I PU3LISHED BY RICHARDSON 6c LORD, AND JAMES LORING. Sold wholesale and retail, a« their Book-Stores, Comhill. i^%^gffig*%#MfogH/>W '\$ 'M^>^Maffg| — ECLIPSES—FOR 1825. 'There- will 'be 'four Eclipses this year, two of the Sun, and two of the Moon, in the following order, viz : I. The first will be a very small eclipse of the Moon May 31st, the latter part of which will be visible, as follows' Beginning 7h. 10m. 1 Middle 7 24 f Appear, time Moon rises 7 84 C evening. End 7 39 ) Wljole duration only 29 Digits eclipsed, 0° 12$' on the Moon's'northern limb. II. The second will be of the Sun, June 16th day, 7h*> 38m. in the morning, but invisible to us on account of the Moon's southern latitude,—Moon's lat. 22° nearly S» III. The third will be of the Moon, November 25th. day, llh. 38m. -

Historic Burial-Places of Boston and Vicinity. by John M

1891.] Historie Burial-places of Boston and Vicinity. 381 HISTORIC BURIAL-PLACES OF BOSTON AND VICINITY. BY JOHN M. MBRRIAM. EVERY student of American History will find in early Boston a favorite subject. In her history are the begin- nings of all the great social, political and religious progress- ive movements toward the present America. However great the pride of the native Bostonian, others not so fortunate must excuse and commend it. ' If Chief Justice Sewall, in his dream of the Saviour's visit to Boston (I. Diai'y, p. 115) could have looked forward a century and more, he might well have expressed even greater admiration for the "Wis- dom of Christ in coming hither and spending some part of his short life here." Among the many objects so strongly stamped as historic by association with the men and events of early Boston, none to-day possesses keener interest to members of the American Antiquarian Society than the old graveyards. It was with great gratification, therefore, that a party of gentlemen many of whom are members of this Society, was permitted last May, by the invitation of Hon. George F. Hoar, to visit the more important of these ancient burial- places, and later, in July, by the courtesy of Mr. Charles Francis Adams, to visit the old burying-ground and other historic places in Quincy. The oldest place of burial in Boston is the King's Chapel Yard on Tremont street. Long before this place was asso- ciated with King's Chapel, it was a graveyard. Tradition, coming from Judge Sewall, through Rev. -

Pdf (Acrobat, Print/Search, 1.7

1 COLLECTIONS OF THE MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETY. 2 Committee of Publication. GEORGE E. ELLIS. WILLIAM H. WHITMORE. HENRY WARREN TORREY. JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL. Electronic Version Prepared by Dr. Ted Hildebrandt 4/6/2002 Gordon College, 255 Grapevine Rd. Wenham, MA. 01984 3 COLLECTIONS OF THE MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETY. Vol. VI. -- FIFTH SERIES. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY. M.DCCCLXXIX 4 UNIVERSITY PRESS: JOHN WILSON AND SON, CAMBRIDGE. SECOND EDITION. 5 PRE FACE. THE Publishing Committee herewith presents to the Society the second volume of the Diary of Samuel Sewall, Printed from the Manuscript in its Cabinet. The text of the volume in- cludes the period from January 14, 1699-1700, to April 14, 1714. Another volume in print will complete the publication of the manuscript Diary. The Judge's Letter-Book will furnish the materials for a fourth volume. The Committee has continued the same system of annotating the text which was adopted in the first volume. Resisting the prompting or opportunity to explain or illustrate the many in- teresting references which the Judge makes to matters of his- torical importance, to an extent which would expand the notes beyond the text, the method pursued, as the reader will observe, has been restricted to occasional comments, and to genealogical and local particulars and references, without quoting authorities easily accessible to the students of our history. The connection between Judge Sewall's family and that of Governor Dudley evidently embarrassed the former, alike in his official position as a magistrate, and in making entries in his diary concerning mat- ters in which they were occasionally at variance. -

Members of the American Academy by Election Year, 1900-1949

Members of the American Academy Listed by election year, 1900-1949 Duff, Alexander Wilmer Elected in 1900 Elected in 1902 (1864-1951) Bailey, Liberty Hyde (1858-1954) Emerton, Ephraim (1851-1935) Balfour, Arthur James (1848-1930) Bates, Arlo (1850-1918) Engler, Adolph Gustav Heinrich Behring, Emil Adolph von Castle, William Ernest (1867-1962) (1844-1930) (1854-1917) Choate, Joseph Hodges (1832-1917) Fritz, John (1822-1913) Burton, Alfred Edgar (1857-1935) Dawson, George Mercer Hale, George Ellery (1868-1938) Clifford, Harry Ellsworth (1849-1901) Halsted, William Stewart (1866-1952) Fernald, Merritt Lyndon (1852-1922) Cremona, Luigi (Antonio Luigi (1873-1950) Hearn, William Edward Gaudienzo Giuseppe) (1830-1903) Fuller, Melville Weston (1826-1888) Delitzsch, Friedrich (1850-1922) (1833-1910) Hoar, George Frisbie (1826-1904) Gardiner, Samuel Rawson Geikie, Archibald (1835-1924) Jackson, Henry (1839-1921) (1829-1902) Howe, William Wirt (1833-1909) Johnson, Lewis Jerome Hadley, Arthur Twining Kohlrausch, Friedrich Wilhelm (1867-1952) (1856-1930) Georg (1840-1910) Keen, William Williams von Hann, Julius Ferdinand Mitchell, William (1832-1900) (1837-1932) (1839-1921) Murray, John (1841-1914) Koch, Robert (Heinrich Hermann Hofman, Heinrich Oscar Richardson, Rufus Byam Robert) (1843-1910) (1852-1924) (1845-1914) Kronecker, Hugo (1839-1914) Horsley, Victor Alexander Haden Seymour, Thomas Day Lyman, Theodore (1874-1954) (1857-1916) (1848-1907) Mall, Franklin Paine (1862-1917) Hough, Theodore (1865-1924) Stephens, Henry Morse Moore, Eliakim Hastings