Decarceration Nation Episode 70 College Behind Bars Joshua Hoe 0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dangerous Summer

theHemingway newsletter Publication of The Hemingway Society | No. 73 | 2021 As the Pandemic Ends Yet the Wyoming/Montana Conference Remains Postponed Until Lynda M. Zwinger, editor 2022 the Hemingway Society of the Arizona Quarterly, as well as acquisitions editors Programs a Second Straight Aurora Bell (the University of Summer of Online Webinars.… South Carolina Press), James Only This Time They’re W. Long (LSU Press), and additional special guests. Designed to Confront the Friday, July 16, 1 p.m. Uncomfortable Questions. That’s EST: Teaching The Sun Also Rises, moderated by Juliet Why We’re Calling It: Conway We’ll kick off the literary discussions with a panel on Two classic posters from Hemingway’s teaching The Sun Also Rises, moderated dangerous summer suggest the spirit of ours: by recent University of Edinburgh A Dangerous the courage, skill, and grace necessary to Ph.D. alumna Juliet Conway, who has a confront the bull. (Courtesy: eBay) great piece on the novel in the current Summer Hemingway Review. Dig deep into n one of the most powerful passages has voted to offer a series of webinars four Hemingway’s Lost Generation classic. in his account of the 1959 bullfighting Fridays in a row in July and August. While Whether you’re preparing to teach it rivalry between matadors Antonio last summer’s Houseguest Hemingway or just want to revisit it with fellow IOrdóñez and Luis Miguel Dominguín, programming was a resounding success, aficionados, this session will review the Ernest Hemingway describes returning to organizers don’t want simply to repeat last publication history, reception, and major Pamplona and rediscovering the bravery year’s model. -

Prohibition Premieres October 2, 3 & 4

Pl a nnerMichiana’s bi-monthly Guide to WNIT Public Television Issue No. 5 September — October 2011 A FILM BY KEN BURNS AND LYNN NOVICK PROHIBITION PREMIERES OCTOBER 2, 3 & 4 BrainGames continues September 29 and October 20 Board of Directors Mary’s Message Mary Pruess Chairman President and GM, WNIT Public Television Glenn E. Killoren Vice Chairmen David M. Findlay Rodney F. Ganey President Mary Pruess Treasurer Craig D. Sullivan Secretary Ida Reynolds Watson Directors Roger Benko Janet M. Botz WNIT Public Television is at the heart of the Michiana community. We work hard every Kathryn Demarais day to stay connected with the people of our area. One way we do this is to actively engage in Robert G. Douglass Irene E. Eskridge partnerships with businesses, clubs and organizations throughout our region. These groups, David D. Gibson in addition to the hundreds of Michiana businesses that help underwrite our programs, William A. Gitlin provide WNIT with constant and immediate contact to our viewers and to the general Tracy D. Graham Michiana community. Kreg Gruber Larry D. Harding WNIT maintains strong partnerships and active working relationship with, among others, James W. Hillman groups representing the performing arts – Arts Everywhere, Art Beat, the Fischoff National Najeeb A. Khan Chamber Music Association, the Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival, the Krasl Art Center in Evelyn Kirkwood Kevin J. Morrison St. Joseph, the Lubeznik Center for the Arts in Michigan City and the Southwest Michigan John T. Phair Symphony; civic and cultural organizations like the Center for History, Fernwood Botanical Richard J. Rice Garden and Nature Center and the Historic Preservation Commission; educational, social Jill Richardson and healthcare organizations such as WVPE National Public Radio, the St. -

Review Essay Ken Burns and Lynn Novick's the Vietnam

Review Essay Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s The Vietnam War MARK PHILIP BRADLEY True confessions: I did not go into the eighteen hours of Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s The Vietnam War with a totally open mind.1 Burns’s 1990 documentary series The Civil War, which made his career, had evoked a storm of controversy, with such leading his- torians as Leon Litwack and Eric Foner offering scathing critiques of how the film depicted African Americans as passive victims and entirely ignored the ways in which the postwar era of Reconstruction became an exercise in white supremacy. As Foner wrote, “Faced with a choice between historical illumination or nostalgia, Burns consis- tently opts for nostalgia.”2 Subsequent documentaries on jazz and World War II always struck me, and in fact many critics, as deliberately skirting potentially subversive counter-narratives in a kind of burnishing of the past.3 And to be quite honest, all of them seemed too long. In the case of Burns and Novick’s earlier series The War (2007) and its fifteen-hour embrace of the greatest generation narrative, Burns’s insular docu- mentary painted World War II as an entirely American affair, with non-white and non- American voices largely to the side. The much-heralded “Ken Burns effect” had never worked its magic on me. When I began to hear the tagline for The Vietnam War in the drumbeat of publicity before it was first aired on PBS last September (you will have to conjure up the melan- choly Peter Coyote voiceover as you read)—“It was begun in good faith by decent peo- ple out of fateful misunderstandings, American overconfidence, and Cold War mis- calculations”—I anticipated a painful eighteen hours. -

The Legacy of American Photojournalism in Ken Burns's

Interfaces Image Texte Language 41 | 2019 Images / Memories The Legacy of American Photojournalism in Ken Burns’s Vietnam War Documentary Series Camille Rouquet Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/647 DOI: 10.4000/interfaces.647 ISSN: 2647-6754 Publisher: Université de Bourgogne, Université de Paris, College of the Holy Cross Printed version Date of publication: 21 June 2019 Number of pages: 65-83 ISSN: 1164-6225 Electronic reference Camille Rouquet, “The Legacy of American Photojournalism in Ken Burns’s Vietnam War Documentary Series”, Interfaces [Online], 41 | 2019, Online since 21 June 2019, connection on 07 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/647 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/interfaces.647 Les contenus de la revue Interfaces sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. THE LEGACY OF AMERICAN PHOTOJOURNALISM IN KEN BURNS’S VIETNAM WAR DOCUMENTARY SERIES Camille Rouquet LARCA/Paris Sciences et Lettres In his review of The Vietnam War, the 18-hour-long documentary series directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick released in September 2017, New York Times television critic James Poniewozik wrote: “The Vietnam War” is not Mr. Burns’s most innovative film. Since the war was waged in the TV era, the filmmakers rely less exclusively on the trademark “Ken Burns effect” pans over still images. Since Vietnam was the “living-room war,” played out on the nightly news, this documentary doesn’t show us the fighting with new eyes, the way “The War” did with its unearthed archival World War II footage. -

Vietnam Revisited

OCTOBER 2017 VIETNAM REVISITED elebrated filmmaker Ken Burns — heralded as “America’s storyteller” for such films as Jazz, Baseball, The Roosevelts, and Brooklyn Bridge — makes television history again this month with the premiere of The Vietnam War, a new 10-part, 18-hour documentary series co-directed by Lynn Novick. CTen years in the making, The Vietnam War tells the epic story of one of the most divisive and controversial events in American history as it has never before been told on film. The immersive narrative reveals the human dimensions of the war through testimony from nearly 80 witnesses, including Americans who fought in the war and others who opposed it, as well as Vietnamese combatants and civilians from both sides of the conflict. Digitally re-mastered archival footage, photographs taken by legendary 20th century photojournalists, historic television broadcasts, evocative home movies, and revelatory audio recordings from inside the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations bring the war and the chaotic era it encompassed to life. More than 120 popular songs that defined the era by The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, Simon and Garfunkel, Janis Joplin, Joni Mitchell, Pete Seeger, and other iconic artists further enhance the storytelling. “The Vietnam War was a decade of agony that took the lives of more than 58,000 Americans,” Burns said. “Not since the Civil War have we as a country been so torn apart. More than 40 years after it ended, we can’t forget Vietnam, and we are still arguing about why it went wrong, who was to blame and whether it was all worth it.” Burns hopes The Vietnam War will inspire national conversations about our country’s history and who we are as Americans. -

Vietnam and PTSD

EDITORIAL An Anniversary Postponed and a Diagnosis Delayed: Vietnam and PTSD More than 40 years after it ended, we can’t forget Vietnam and we are still arguing about why it went wrong, who was to blame and whether it was all worth it. Ken Burns1 any events both personal and public have this year of so much loss and heroism, I encour- been deferred during the 15 plus months age you to find a way to thank Vietnam veterans M of the pandemic. Almost everyone has who may have received the opposite of gratitude an example of a friend or family member who when they initially returned home. would have been sitting at what President Biden, As my small contribution to the commemora- Cynthia Geppert is during his memorial speech for the 500,000 vic- tion, this editorial will focus on the psychiatric Editor-in-Chief; tims of the virus referred to as the “empty chair” disorder of memory: posttraumatic stress disorder Chief, Consultation at a holiday gathering sans COVID-19.2 For (PTSD) and how the Vietnam War brought defi- Psychiatry and Ethics, New Mexico VA Health many in our country, part of the agonizing ef- nition—albeit delayed—to the agonizing diagno- Care System; and fort to awaken from the long nightmare of the sis that too many veterans experience. Professor and pandemic is to resume the rhythm of rituals na- The known clinical entity of PTSD is ancient. Director of Ethics Education at the tional, local, and personal that mark the year Narrative descriptions of the disorder are written University of New with meaning and offer rest and rejuvenation in the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh and in Mexico School of from the daily toil of duty. -

Minnesota Remembers Vietnam

MINNESOTA REMEMBERS VIETNAM A COLLABORATION OF THE KSMQ-TV LAKELAND PBS PIONEER PUBLIC TV PRAIRIE PUBLIC TWIN CITIES PBS WDSE-WRPT To our COMMUNITIES Our year-long, statewide initiative called Minnesota Remembers Vietnam was conceived well over two years ago when we learned that filmmakers Ken Burns and Lynn Novick were going to present to America their comprehensive and definitive work on Vietnam. We took pause at Twin Cities PBS (TPT) and asked: “What could we do to bring this story home? What might we do to honor and give voice to those in Minnesota whose lives were touched by this confusing, divisive, and tumultuous period in American history? And what might we do to create understanding and healing?” We set our sights very high, and the collective $2 million raised in public support from the State of Minnesota’s Legacy Fund, generous foundations and organizations, and our community, allowed us to dream big and create what has been the largest and one of the most important projects in TPT’s 60-year history. In partnership with the five other PBS stations in the state, we explored the war from all sides. It has been a deeply moving experience for all of us at TPT and the stations of the MPTA, and we feel much richer for having been a part of this. I can tell you very sincerely that in my four decades of working with PBS, I've never been involved in a project that was so universally embraced. The unifying message that I heard time and time again from those who supported the war, those who demonstrated against it, and those who only learned about it through the history books was that the time was now to seize the moment to honor those who served their country during this tumultuous and confusing time… people who were shunned and endured hardships upon returning home, and who, until very recently, did not feel welcome to tell their stories, both the joyful memories of friendships and camaraderie and the haunting memories of battle. -

Teacher's Guide

TEACHER’S GUIDE Additional Resources: PBS Resources MISSION US: “Prisoner in My Homeland” The creators of MISSION US have assembled the following list of PBS Resources to enhance and extend teacher and student learning about the people, places, and historical events depicted in the game. PBS LearningMedia, “The Fred T. Korematsu Institute.” https://ny.pbslearningmedia.org/collection/korematsu-institute-collection/ This collection from the education non-profit, The Fred T. Korematsu Institute, includes teacher- authored lessons related to documentary films on the Japanese American incarceration experience. Lessons are paired with short clips from the films. PBS LearningMedia, “Injustice at Home.” https://ny.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/injustice-at-home/injustice-at-home-the-japanese- american-experience-of-the-world-war-ii-era/ This educational resource includes five educational videos and an inquiry-based unit of study. Topics include help Executive Order 9066 and the resulting incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II; the failure of political leadership; the military experience of Japanese Americans; and historic discrimination and racial prejudice against Japanese Americans. Produced by KSPS Public Television and Eastern Washington educators. PBS LearningMedia, “Japanese Internment Camps: Teaching with Primary Sources.” https://ny.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/b10f6426-c8eb-4a6e-ac74-67ed6fb1dafb/japanese- internment-camps/ This inquiry kit features a series of Library of Congress sources related to the American internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. PBS Website for Children of the Camps. Directed by Stephen Holsapple, 1999. https://www.pbs.org/childofcamp/history/ The accompanying website for Children of the Camps, a one-hour documentary that portrays the poignant stories of six Japanese Americans who were interned as children in US concentration camps during World War II. -

Vegas PBS Source, Volume No

Trusted. Valued. Essential. SEPTEMBER 2019 Vegas PBS A Message from the Management Team General Manager General Manager Tom Axtell, Vegas PBS Educational Media Services Director Niki Bates Production Services Director Kareem Hatcher Business Manager Brandon Merrill Communications and Brand Management Director Allison Monette Content Director Explore a True American Cyndy Robbins Workforce Training & Economic Development Director Art Form in Country Music Debra Solt Interim Director of Development and Strategic Relations en Burns is television’s most prolific documentarian, and PBS is the Clark Dumont exclusive home he has chosen for his work. Member donations make it Engineering, IT and Emergency Response Director possible for us to devote enough research and broadcast time to explore John Turner the facts, nuances and impact of history in our daily lives and our shared SOUTHERN NEVADA PUBLIC TELEVISION BOARD OF DIRECTORS American values. Since his first film in 1981, Ken Burns has been telling Executive Director Kunique and fascinating stories of the United States. Tom Axtell, Vegas PBS Ken has provided historical insights on events like The Civil War, Prohibition and President The Vietnam War. He has investigated the impact of important personalities in The Tom Warden, The Howard Hughes Corporation Roosevelts, Thomas Jefferson and Mark Twain, and signature legacies like The Vice President Brooklyn Bridge,The National Parks and The Statute of Liberty. Now the filmmaker Clark Dumont, Dumont Communications, LLC explores another thread of the American identity in Country Music. Beginning Sunday, Secretary September 15 at 8 p.m., step back in time and explore the remarkable stories of the Nora Luna, UNR Cooperative Extension people and places behind this true American art form in eight two-hour segments. -

Reportto the Community

REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY Public Broadcasting for Greater Washington FISCAL YEAR 2020 | JULY 1, 2019 – JUNE 30, 2020 Serving WETA reaches 1.6 million adults per week via local content platforms the Public Dear Friends, Now more than ever, WETA is a vital resource to audiences in Greater THE WETA MISSION in a Time Washington and around the nation. This year, with the onset of the Covid-19 is to produce and hours pandemic, our community and our country were in need. As the flagship 1,200 distribute content of of new national WETA programming public media station in the nation’s capital, WETA embraced its critical role, of Need responding with enormous determination and dynamism. We adapted quickly intellectual integrity to reinvent our work and how we achieve it, overcoming myriad challenges as and cultural merit using we pursued our mission of service. a broad range of media 4 billion minutes The American people deserved and expected information they could rely to reach audiences both of watch time on the PBS NewsHour on. WETA delivered a wealth of meaningful content via multiple media in our community and platforms. Amid the unfolding global crisis and roiling U.S. politics, our YouTube channel nationwide. We leverage acclaimed news and public affairs productions provided trusted reporting and essential context to the public. our collective resources to extend our impact. of weekly at-home learning Despite closures of local schools, children needed to keep learning. WETA 30 hours programs for local students delivered critical educational resources to our community. We significantly We will be true to our expanded our content offerings to provide access to a wide array of at-home values; and we respect learning assets — on air and online — in support of students, educators diversity of views, and families. -

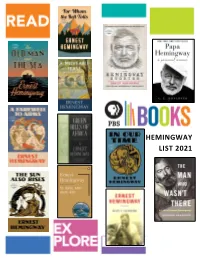

Hemingway List 2021

HEMINGWAY LIST 2021 Ernest Hemingway wrote for the common person, so that anyone could understand his manifold adventures with ease. HEMINGWAY, a three-part, six-hour documentary film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, examines the visionary work and the turbulent life of Ernest Hemingway, one of the greatest and most influential writers America has ever produced. Interweaving his eventful biography — a life lived at the ultimately treacherous nexus of art, fame, and celebrity — with carefully selected excerpts from his iconic short stories, novels, and non-fiction, the series reveals the brilliant, ambitious, charismatic, and complicated man behind the myth, and the art he created. This list compiles a selection of his canonical works, as well as biographies. Join the conversation at pbs.org/hemingwayevents, learn more at pbsbooks.org/hemingway, or follow on social #HemingwayPBS. BOOKS BY HEMINGWAY The Old Man and the Sea A Moveable Feast In Our Time This minimalistic 1953 Pulitzer Prize Published in 1964, this book examines << Ernest Hemingway winning novella describes the epic the glamorous happenings of creative This collection of short stories and struggle between a sun-weary Cuban minded gatherings in 1920’s Paris. The vignettes demonstrated Hemingway’s fisherman and a giant marlin as they story comes face to face with trademark knack for invoking a wide hash it out in the deep waters of the Gulf. Hemingway’s real-life interactions with spectrum of emotions through sparse It is often cited as the chief catalyst for writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald, James and simple prose. The book, published Hemingway winning the 1954 Nobel Joyce, and Gertrude Stein. -

July 30, 2017 TCA Panelist Bios

July 30, 2017 TCA Panelist Bios Ken Burns Ken Burns has been making documentary films for almost 40 years. Since the Academy Award-nominated Brooklyn Bridge in 1981, Ken has gone on to direct and produce some of the most acclaimed historical documentaries ever made, including The Civil War; Baseball; Jazz, The Statue of Liberty; Huey Long; Lewis and Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery; Frank Lloyd Wright; Mark Twain; Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson; The War; The National Parks: America’s Best Idea; The Roosevelts: An Intimate History; Jackie Robinson; and, most recently, Defying the Nazis: The Sharps’ War. A December 2002 poll conducted by Real Screen Magazine listed The Civil War as second only to Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North as the “most influential documentary of all time,” and named Ken Burns and Robert Flaherty as the “most influential documentary makers” of all time. In March 2009, David Zurawik of The Baltimore Sun said, “… Burns is not only the greatest documentarian of the day, but also the most influential filmmaker period. That includes feature filmmakers like George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. I say that because Burns not only turned millions of persons onto history with his films, he showed us a new way of looking at our collective past and ourselves.” The late historian Stephen Ambrose said of his films, “More Americans get their history from Ken Burns than any other source.” Future projects include films on the history of country music, Ernest Hemingway, and the history of stand-up comedy.