Diptera): Tests of Alternative Morphological Hypotheses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTHROPOD COMMUNITIES and PASSERINE DIET: EFFECTS of SHRUB EXPANSION in WESTERN ALASKA by Molly Tankersley Mcdermott, B.A./B.S

Arthropod communities and passerine diet: effects of shrub expansion in Western Alaska Item Type Thesis Authors McDermott, Molly Tankersley Download date 26/09/2021 06:13:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/7893 ARTHROPOD COMMUNITIES AND PASSERINE DIET: EFFECTS OF SHRUB EXPANSION IN WESTERN ALASKA By Molly Tankersley McDermott, B.A./B.S. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences University of Alaska Fairbanks August 2017 APPROVED: Pat Doak, Committee Chair Greg Breed, Committee Member Colleen Handel, Committee Member Christa Mulder, Committee Member Kris Hundertmark, Chair Department o f Biology and Wildlife Paul Layer, Dean College o f Natural Science and Mathematics Michael Castellini, Dean of the Graduate School ABSTRACT Across the Arctic, taller woody shrubs, particularly willow (Salix spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and alder (Alnus spp.), have been expanding rapidly onto tundra. Changes in vegetation structure can alter the physical habitat structure, thermal environment, and food available to arthropods, which play an important role in the structure and functioning of Arctic ecosystems. Not only do they provide key ecosystem services such as pollination and nutrient cycling, they are an essential food source for migratory birds. In this study I examined the relationships between the abundance, diversity, and community composition of arthropods and the height and cover of several shrub species across a tundra-shrub gradient in northwestern Alaska. To characterize nestling diet of common passerines that occupy this gradient, I used next-generation sequencing of fecal matter. Willow cover was strongly and consistently associated with abundance and biomass of arthropods and significant shifts in arthropod community composition and diversity. -

Diptera, Empidoidea) 263 Doi: 10.3897/Zookeys.365.6070 Research Article Launched to Accelerate Biodiversity Research

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 365: 263–278 (2013) DNA barcoding of Hybotidae (Diptera, Empidoidea) 263 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.365.6070 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.zookeys.org Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Using DNA barcodes for assessing diversity in the family Hybotidae (Diptera, Empidoidea) Zoltán T. Nagy1, Gontran Sonet1, Jonas Mortelmans2, Camille Vandewynkel3, Patrick Grootaert2 1 Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, OD Taxonomy and Phylogeny (JEMU), Rue Vautierstraat 29, 1000 Brussels, Belgium 2 Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, OD Taxonomy and Phylogeny (Ento- mology), Rue Vautierstraat 29, 1000 Brussels, Belgium 3 Laboratoire des Sciences de l’eau et environnement, Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Avenue Albert Thomas, 23, 87060 Limoges, France Corresponding author: Zoltán T. Nagy ([email protected]) Academic editor: K. Jordaens | Received 7 August 2013 | Accepted 27 November 2013 | Published 30 December 2013 Citation: Nagy ZT, Sonet G, Mortelmans J, Vandewynkel C, Grootaert P (2013) Using DNA barcodes for assessing diversity in the family Hybotidae (Diptera, Empidoidea). In: Nagy ZT, Backeljau T, De Meyer M, Jordaens K (Eds) DNA barcoding: a practical tool for fundamental and applied biodiversity research. ZooKeys 365: 263–278. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.365.6070 Abstract Empidoidea is one of the largest extant lineages of flies, but phylogenetic relationships among species of this group are poorly investigated and global diversity remains scarcely assessed. In this context, one of the most enigmatic empidoid families is Hybotidae. Within the framework of a pilot study, we barcoded 339 specimens of Old World hybotids belonging to 164 species and 22 genera (plus two Empis as outgroups) and attempted to evaluate whether patterns of intra- and interspecific divergences match the current tax- onomy. -

View the PDF File of the Tachinid Times, Issue 10

The Tachinid Times ISSUE 10 February 1997 Jim O’Hara, editor Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada, Biological Resources Program Eastern Cereal and Oilseed Research Centre C.E.F., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0C6 Correspondence: [email protected] This issue marks the 10th anniversary of The Resolutions adopted by International Conference on Tachinid Times. Though the appearance of the hardcopy Biological Control version of this newsletter has changed little over the An International Conference entitled, Technology years, the mode of production of the newsletter has Transfer in Biological Control: from Research to changed considerably. The first few issues were Practice, was held in Montpellier, France, 9-11 produced before personal computers were commonplace September 1996. The Conference was jointly organized in the workforce, and were compiled solely from letters by the International Organization for Biological Control sent by the readership. News items then began reaching (IOBC/OILB) and C.I.L.B.A./AGROPOLIS. me on diskettes, and now the Internet is the most Resolutions adopted by the participants are as follows common method used for submission of news. (reproduced from d’Agropolis, La lettre No. 38): A new medium for the exchange of information is now - WHEREAS biological control and IPM have upon us in the form of the World Wide Web, and its contributed significantly to environmentally compatible potential for the dissemination of scientific knowledge is and sustainable pest management for over 100 years with quickly being realized. Already there are “products” minimal non-target effects; appearing on the WWW which are unavailable in - WHEREAS biological control and IPM are eco- hardcopy, and it will not be long before some scientific logically-based processes that depend on a strong research journals publish in electronic versions only. -

Burmese Amber Taxa

Burmese (Myanmar) amber taxa, on-line supplement v.2021.1 Andrew J. Ross 21/06/2021 Principal Curator of Palaeobiology Department of Natural Sciences National Museums Scotland Chambers St. Edinburgh EH1 1JF E-mail: [email protected] Dr Andrew Ross | National Museums Scotland (nms.ac.uk) This taxonomic list is a supplement to Ross (2021) and follows the same format. It includes taxa described or recorded from the beginning of January 2021 up to the end of May 2021, plus 3 species that were named in 2020 which were missed. Please note that only higher taxa that include new taxa or changed/corrected records are listed below. The list is until the end of May, however some papers published in June are listed in the ‘in press’ section at the end, but taxa from these are not yet included in the checklist. As per the previous on-line checklists, in the bibliography page numbers have been added (in blue) to those papers that were published on-line previously without page numbers. New additions or changes to the previously published list and supplements are marked in blue, corrections are marked in red. In Ross (2021) new species of spider from Wunderlich & Müller (2020) were listed as being authored by both authors because there was no indication next to the new name to indicate otherwise, however in the introduction it was indicated that the author of the new taxa was Wunderlich only. Where there have been subsequent taxonomic changes to any of these species the authorship has been corrected below. -

Diptera: Empidoidea), with a Redefinition of the Tribe Ocydromiini

© Copyright Australian Museum, 2000 Records of the Australian Museum (2000) Vol. 52: 161–186. ISSN 0067–1975 Revision of the Genus Apterodromia (Diptera: Empidoidea), With a Redefinition of the Tribe Ocydromiini BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR1 AND JEFFREY M. CUMMING 2 1 Zoologisches Forschungsinstitut und Museum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, D-53113 Bonn, Germany [email protected] 2 Systematic Entomology Section, ECORC, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, K.W. Neatby Building, C.E.F., Ottawa, ON, Canada K1A 0C6 [email protected] ABSTRACT. The Australian endemic genus Apterodromia Oldroyd (Diptera: Empidoidea) is revised and includes four apterous species (A. evansi Oldroyd, A. minuta n.sp, A. setosa n.sp., and A. tasmanica n.sp.) and eight fully winged species (A. aurea n.sp., A. bickeli n.sp., A. irrorata n.sp., A. monticola n.sp., A. pala n.sp., A. spilota n.sp., A. tonnoiri n.sp., and A. vespertina n.sp.). The male of A. evansi is described and zoogeographic patterns of the genus are discussed. On the basis of wing venation and male terminalia Apterodromia is transferred from the Tachydromiinae to the tribe Ocydromiini (subfamily Ocydromiinae). The Ocydromiini is redefined, two new genera (Neotrichina n.gen. and Leptodromia n.gen.) are described, and all included genera are listed. Keys to major lineages of Australian Empidoidea and Southern Hemisphere genera of Ocydromiini are provided. The following new combinations are listed: Hoplopeza tachydromiaeformis (Bezzi), Leptodromia bimaculata (Bezzi), Neotrichina abdominalis (Collin), N. digna (Collin), N. digressa (Collin), N. distincta (Collin), N. elegans (Bigot), N. fida (Collin), N. indiga (Collin), N. -

1 U of Ill Urbana-Champaign PEET

U of Ill Urbana-Champaign PEET: A World Monograph of the Therevidae (Insecta: Diptera) Participant Individuals: CoPrincipal Investigator(s) : David K Yeates; Brian M Wiegmann Senior personnel(s) : Donald Webb; Gail E Kampmeier Post-doc(s) : Kevin C Holston Graduate student(s) : Martin Hauser Post-doc(s) : Mark A Metz Undergraduate student(s) : Amanda Buck; Melissa Calvillo Other -- specify(s) : Kristin Algmin Graduate student(s) : Hilary Hill Post-doc(s) : Shaun L Winterton Technician, programmer(s) : Brian Cassel Other -- specify(s) : Jeffrey Thorne Post-doc(s) : Christine Lambkin Other -- specify(s) : Ann C Rast Senior personnel(s) : Steve Gaimari Other -- specify(s) : Beryl Reid Technician, programmer(s) : Joanna Hamilton Undergraduate student(s) : Claire Montgomery; Heather Lanford High school student(s) : Kate Marlin Undergraduate student(s) : Dmitri Svistula Other -- specify(s) : Bradley Metz; Erica Leslie Technician, programmer(s) : Jacqueline Recsei; J. Marie Metz Other -- specify(s) : Malcolm Fyfe; David Ferguson; Jennifer Campbell; Scott Fernsler Undergraduate student(s) : Sarah Mathey; Rebekah Kunkel; Henry Patton; Emilia Schroer Technician, programmer(s) : Graham Teakle Undergraduate student(s) : David Carlisle; Klara Kim High school student(s) : Sara Sligar Undergraduate student(s) : Emmalyn Gennis Other -- specify(s) : Iris R Vargas; Nicholas P Henry Partner Organizations: Illinois Natural History Survey: Financial Support; Facilities; Collaborative Research Schlinger Foundation: Financial Support; In-kind Support; Collaborative Research 1 The Schlinger Foundation has been a strong and continuing partner of the therevid PEET project, providing funds for personnel (students, scientific illustrator, data loggers, curatorial assistant) and expeditions, including the purchase of supplies, to gather unknown and important taxa from targeted areas around the world. -

Diptera) Diversity in a Patch of Costa Rican Cloud Forest: Why Inventory Is a Vital Science

Zootaxa 4402 (1): 053–090 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4402.1.3 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C2FAF702-664B-4E21-B4AE-404F85210A12 Remarkable fly (Diptera) diversity in a patch of Costa Rican cloud forest: Why inventory is a vital science ART BORKENT1, BRIAN V. BROWN2, PETER H. ADLER3, DALTON DE SOUZA AMORIM4, KEVIN BARBER5, DANIEL BICKEL6, STEPHANIE BOUCHER7, SCOTT E. BROOKS8, JOHN BURGER9, Z.L. BURINGTON10, RENATO S. CAPELLARI11, DANIEL N.R. COSTA12, JEFFREY M. CUMMING8, GREG CURLER13, CARL W. DICK14, J.H. EPLER15, ERIC FISHER16, STEPHEN D. GAIMARI17, JON GELHAUS18, DAVID A. GRIMALDI19, JOHN HASH20, MARTIN HAUSER17, HEIKKI HIPPA21, SERGIO IBÁÑEZ- BERNAL22, MATHIAS JASCHHOF23, ELENA P. KAMENEVA24, PETER H. KERR17, VALERY KORNEYEV24, CHESLAVO A. KORYTKOWSKI†, GIAR-ANN KUNG2, GUNNAR MIKALSEN KVIFTE25, OWEN LONSDALE26, STEPHEN A. MARSHALL27, WAYNE N. MATHIS28, VERNER MICHELSEN29, STEFAN NAGLIS30, ALLEN L. NORRBOM31, STEVEN PAIERO27, THOMAS PAPE32, ALESSANDRE PEREIRA- COLAVITE33, MARC POLLET34, SABRINA ROCHEFORT7, ALESSANDRA RUNG17, JUSTIN B. RUNYON35, JADE SAVAGE36, VERA C. SILVA37, BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR38, JEFFREY H. SKEVINGTON8, JOHN O. STIREMAN III10, JOHN SWANN39, PEKKA VILKAMAA40, TERRY WHEELER††, TERRY WHITWORTH41, MARIA WONG2, D. MONTY WOOD8, NORMAN WOODLEY42, TIFFANY YAU27, THOMAS J. ZAVORTINK43 & MANUEL A. ZUMBADO44 †—deceased. Formerly with the Universidad de Panama ††—deceased. Formerly at McGill University, Canada 1. Research Associate, Royal British Columbia Museum and the American Museum of Natural History, 691-8th Ave. SE, Salmon Arm, BC, V1E 2C2, Canada. Email: [email protected] 2. -

Zootaxa, Empidoidea (Diptera)

ZOOTAXA 1180 The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera) BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR & JEFFREY M. CUMMING Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR & JEFFREY M. CUMMING The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera) (Zootaxa 1180) 172 pp.; 30 cm. 21 Apr. 2006 ISBN 1-877407-79-8 (paperback) ISBN 1-877407-80-1 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2006 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41383 Auckland 1030 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2006 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) Zootaxa 1180: 1–172 (2006) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1180 Copyright © 2006 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera) BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR1 & JEFFREY M. CUMMING2 1 Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Invertebrate Biodiversity, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, C.E.F., Ottawa, ON, Canada -

Zootaxa 414: 1–15 (2004) ISSN 1175-5326 (Print Edition) ZOOTAXA 414 Copyright © 2004 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (Online Edition)

Zootaxa 414: 1–15 (2004) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 414 Copyright © 2004 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Acraspisoides gen. nov. (Diptera: Therevidae: Agapophytinae): a new genus of stiletto-flies from Australia HILARY N. HILL & SHAUN L. WINTERTON Department of Entomology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, N.C. 27695, U.S.A. [email protected] Abstract A new Australian genus of Therevidae, Acraspisoides gen. nov., comprising a single species (A. helviarta sp. nov.) is described and illustrated. This new genus is placed within the subfamily Agapophytinae based on the presence of velutum patches on the fore and hind femora. Acrasp- isoides is easily separated from other agapophytine genera by the combination of characters: large ventral lobe on aedeagus, multiple rows of postocular setae in both sexes, antennae positioned low on frons, and wing cell m3 closed. Cladistic analyses using all genera of Agapophytinae (including Acraspisoides) based on adult morphological characters and sequence data of the protein-encoding gene, elongation factor-1α (EF-1α), were performed to determine the phylogenetic placement of Acraspisoides gen. nov. in the subfamily. Analysis of the combined morphological and molecular matrices produced two most parsimonious trees, placing Acraspisoides gen. nov. as the most basal genus of Agapophytinae. Key words: Diptera, Asiloidea, Therevidae, Agapophytinae, Acraspisoides, taxonomy, phyloge- netic, EF-1α, Australia Introduction Stiletto-flies (Diptera: Therevidae) are of virtually worldwide distribution, occurring in all geographical regions with the exception of Antarctica (Irwin & Lyneborg 1989). Therev- ids occur in a multitude of habitats including rainforests, coastal dunes, and deserts, with greatest diversity apparent in arid environments where the sandy, friable soils provide a suitable habitat for the soil-dwelling larvae (Irwin 1976; Winterton et al. -

Insects and Related Arthropods Associated with of Agriculture

USDA United States Department Insects and Related Arthropods Associated with of Agriculture Forest Service Greenleaf Manzanita in Montane Chaparral Pacific Southwest Communities of Northeastern California Research Station General Technical Report Michael A. Valenti George T. Ferrell Alan A. Berryman PSW-GTR- 167 Publisher: Pacific Southwest Research Station Albany, California Forest Service Mailing address: U.S. Department of Agriculture PO Box 245, Berkeley CA 9470 1 -0245 Abstract Valenti, Michael A.; Ferrell, George T.; Berryman, Alan A. 1997. Insects and related arthropods associated with greenleaf manzanita in montane chaparral communities of northeastern California. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-167. Albany, CA: Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service, U.S. Dept. Agriculture; 26 p. September 1997 Specimens representing 19 orders and 169 arthropod families (mostly insects) were collected from greenleaf manzanita brushfields in northeastern California and identified to species whenever possible. More than500 taxa below the family level wereinventoried, and each listing includes relative frequency of encounter, life stages collected, and dominant role in the greenleaf manzanita community. Specific host relationships are included for some predators and parasitoids. Herbivores, predators, and parasitoids comprised the majority (80 percent) of identified insects and related taxa. Retrieval Terms: Arctostaphylos patula, arthropods, California, insects, manzanita The Authors Michael A. Valenti is Forest Health Specialist, Delaware Department of Agriculture, 2320 S. DuPont Hwy, Dover, DE 19901-5515. George T. Ferrell is a retired Research Entomologist, Pacific Southwest Research Station, 2400 Washington Ave., Redding, CA 96001. Alan A. Berryman is Professor of Entomology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-6382. All photographs were taken by Michael A. Valenti, except for Figure 2, which was taken by Amy H. -

A New Genus of Empididae (Diptera) with Enlarged Postpedicels in Mid- Cretaceous Burmese Amber - in PRESS

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340003977 A new genus of Empididae (Diptera) with enlarged postpedicels in mid- Cretaceous Burmese amber - IN PRESS Article in Historical Biology · April 2020 DOI: 10.1080/08912963.2020.1743700 CITATIONS READS 0 52 2 authors: George Poinar Fernando E. Vega Oregon State University United States Department of Agriculture 764 PUBLICATIONS 13,423 CITATIONS 232 PUBLICATIONS 5,428 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Coffee berry borer View project Taxonomy of neotropical and fossil Strepsiptera (Insecta) View project All content following this page was uploaded by Fernando E. Vega on 21 March 2020. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Historical Biology An International Journal of Paleobiology ISSN: 0891-2963 (Print) 1029-2381 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ghbi20 A new genus of Empididae (Diptera) with enlarged postpedicels in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber George O. Poinar & Fernando E. Vega To cite this article: George O. Poinar & Fernando E. Vega (2020): A new genus of Empididae (Diptera) with enlarged postpedicels in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber, Historical Biology, DOI: 10.1080/08912963.2020.1743700 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2020.1743700 Published online: 21 Mar 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ghbi20 HISTORICAL BIOLOGY https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2020.1743700 ARTICLE A new genus of Empididae (Diptera) with enlarged postpedicels in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber George O. -

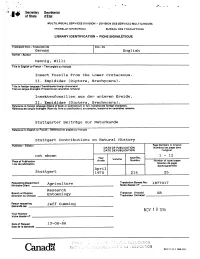

Hennig (1970) Insect Fossils from the Lower Cretaceous. II. Empididae

,- ~- . til. ."""r Secretary Secretariat of State d'Etat MULTILINGUAL SERVICES DIVISION - DIVISION DES SERVICES MUlTILINGUES TRANSLATION BUREAU BUREAU DES TRADLJCTIONS LIBRARY IDENTIFICATION - FICHE SIGNALETIQUE Translated from - Traduction de Into - En German English Author - ~uteur Hennig, Willi Title in Eraglish or French - Titre anglais ou fran~ais Insect Fossils From the Lower Cretaceous. II. Empididae (Diptera, Brachycera). Title in foreign language (Transliterate foreign characters) Titre en langue 'trang6re (Transcrire en caractAres romains) Insektenfossilien aus der unteren Kreide. II. Empididae (Diptera, Brachycera)~ Refere~ce in foreign language (Name of book or publication) in full, transliterate foreign characters. Rif4renc8 en langue ~trangtre (Nom du livre au publication), au complet, transcrire en caractAres romains. stuttgarter BeitrMge zur Naturkunde Reference in English or French - A6f6rence en anglais ou fran~ais stuttgart Contributions on Natural History Publisher .. Editeur Page Numbers in original DATE OF PUBLICATION Num'ros des pages dans DATE DE PUBLICAilON I'original not shown 1 12 Yeor Issue No. - Volume Place of Publication Annt1e Num6ro Number of typed pages Lieu de publieation Nombre de pages dactylographiees April Stuttgart 1970 214 25 Requesting Department Translation Bureau No. 1877017 Minist6re-CUent Agriculture Notre dossier nO _ Research. BranchOi~cdonoyor DivisionO~~lon ~_~t o_~~o_o~~~~_~~1 ~ Translator (Initials) AB __ Traducteur (lnitiales) __.,------------ Person requesting Jeff Curnmi.ng Demand6 par ~__--- ~_ NO\' 19 1986 Your Numbllr Vatr. dossier nO ~ _ Date of Request 13-08-86 Date de la derilande _ l •• Can. ada SEC 5·111 (84-10) Secretary Secretariat of State d'~tat MULT'L'NGUAL SERVICES DIVISION - DIVISION DES SERVICES MULTILINGUES TRANSLATION IlUREAU BUREAU DES TRADUCTIONS Client's No.-No du client Department Minist6re Division/Branch - Division/Direction City - Ville Agriculture Research ottawa, Entomology C.E.F.