Flies and Flowers Ii: Floral Attractants and Rewards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carl Von Linnén Merkitys Biologian Ja Erityisesti Suomen Biologian Kehitykselle

AURAICA Vol. 1, 2008: 93–100 Scripta a Societate Porthan edita Carl von Linnén merkitys biologian ja erityisesti Suomen biologian kehitykselle Petter Portin Kaikkien aikojen merkittävimmän kasvitieteilijän, Pohjoismaiden suurimman biologin, ruotsalaisen Carl von Linnén (1707–78) merkitys biologian yleiselle kehitykselle on erittäin merkittävä. Hän on ainoa 1700-luvulla vaikuttanut luonnontieteilijä, joka edelleen on maailmankuulu ja jonka työn arvo on selvästi havaittavissa vielä tänä päivänä. Linnén merkitys biologian kehitykselle on suunnattoman suuri kahdesta painavasta syystä. Ensinnäkin Linné on eliöiden luokitteluopin eli taksonomian isä. Hän kuvasi, nimesi ja järjesti valtavan määrän kasveja ja eläimiä. Taksonomia sinänsä on ensiarvoisen tärkeää biologisen luonnon lähes rajattoman moninaisuuden hallitse- miseksi. Lisäksi, vaikka Linnén itse ajattelikin, että lajeja on niin paljon kuin Luoja niitä alussa loi, hänen luomansa eliöiden hierarkkinen luokittelu avasi tietä evoluutioteorialle, mikä teoria puolestaan tärkein biologiaan yhtenäistävä teoria. Usein siteeratun lauseen mukaan biologiassa mikään ei käy järkeen muuten kuin evoluution valossa. Toinen Linnén suuri idea ja tärkeä uudistus on eliöiden niin sanottu binomiaalinimistö, jonka mukaan jokaisella kasvilla ja eläimellä on suku- ja lajinimestä koostuva kaksiosainen tieteellinen nimi. Niinpä esimerkiksi variksen tieteellinen nimi on Corvus corone , korpin Corvus corax ja naakan Corvus monedula . Nämä lajit siis kuuluvat kaikki variksen sukuun, Corvus , ja ovatkin polveutumisensa -

Of Dahlia Myths.Pub

Cavanilles’ detailed illustrations established the dahlia in the botanical taxonomy In 1796, the third volume of “Icones” introduced two more dahlia species, named D. coccinea and D. rosea. They also were initially thought to be sunflowers and had been brought to Spain as part of the Alejandro Malaspina/Luis Neé expedition. More than 600 drawings brought the plant collection to light. Cavanilles, whose extensive correspondence included many of Europe’s leading botanists, began to develop a following far greater than his title of “sacerdote” (priest, in French Abbé) ever would have offered. The A. J. Cavanilles archives of the present‐day Royal Botanical Garden hold the botanist’s sizable oeu‐ vre, along with moren tha 1,300 letters, many dissertations, studies, and drawings. In time, Cavanilles achieved another goal: in 1801, he was finally appointed professor and director of the garden. Regrettably, he died in Madrid on May 10, 1804. The Cavanillesia, a tree from Central America, was later named for this famousMaterial Spanish scientist. ANDERS DAHL The lives of Dahl and his Spanish ‘godfather’ could not have been any more different. Born March 17,1751, in Varnhem town (Västergötland), this Swedish botanist struggled with health and financial hardship throughout his short life. While attending school in Skara, he and several teenage friends with scientific bent founded the “Swedish Topographic Society of Skara” and sought to catalogue the natural world of their community. With his preacher father’s support, the young Dahl enrolled on April 3, 1770, at Uppsala University in medicine, and he soon became one of Carl Linnaeus’ students. -

Processing Tomato Enterprise Management Plan Tomato Potato Psyllid Processing Tomato Enterprise Management Plan

Processing tomato Enterprise management plan Tomato potato psyllid Processing tomato enterprise management plan CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 UNDERSTANDING PEST AND PATHOGEN BIOLOGY AND THEIR IDENTIFICATION 2 IDENTIFYING RISK PATHWAYS 5 APPLYING CONTROL AND MANAGEMENT OPTIONS 6 BIOSECURITY AWARENESS AND IMPLEMENTATION 12 MOVEMENT OF FRUIT TO PROCESSING FACILITY 13 PERMIT 14 APPENDIX 1 — Preliminary results 15 APPENDIX 2 — Biological control results 19 APPENDIX 3 — Chemical control results 23 MY NOTES 27 Tomato potato psyllid Processing tomato enterprise management plan 1 INTRODUCTION Tomato potato psyllid (TPP) is supporting ongoing efforts to renew and a serious pest of Processing maintain market access, as well as underpin tomatoes. TPP is the vector certification and assurance schemes. of the bacterium Candidatus Our aim is to build on current best practice Liberibacter solanacearum* to include the management of TPP, without (CLso) which is associated with creating unnecessary additional work. a range of symptoms that affect the production and economic THIS PLAN INCLUDES FIVE KEY performance of your crop. COMPONENTS: TPP WAS FIRST DETECTED TPP was first detected on mainland Australia UNDERSTANDING PEST AND in Western Australia (WA) in February 2017. ON MAINLAND AUSTRALIA PATHOGEN BIOLOGY AND THEIR This prompted a comprehensive biosecurity IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA IN response to minimise the impact of TPP on IDENTIFICATION FEBRUARY 2017. Australian businesses. After national agreement TPP could not be IDENTIFYING RISK PATHWAYS * As at October 2018, surveillance eradicated, efforts focussed on developing the confirms that CLso is not present science, biosecurity and business systems to in WA improve the capacity of growers and industry to manage TPP. APPLYING CONTROL AND An essential component of transition to MANAGEMENT OPTIONS management is the development and implementation of enterprise management plans for affected industries. -

Diptera, Empidoidea) 263 Doi: 10.3897/Zookeys.365.6070 Research Article Launched to Accelerate Biodiversity Research

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 365: 263–278 (2013) DNA barcoding of Hybotidae (Diptera, Empidoidea) 263 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.365.6070 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.zookeys.org Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Using DNA barcodes for assessing diversity in the family Hybotidae (Diptera, Empidoidea) Zoltán T. Nagy1, Gontran Sonet1, Jonas Mortelmans2, Camille Vandewynkel3, Patrick Grootaert2 1 Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, OD Taxonomy and Phylogeny (JEMU), Rue Vautierstraat 29, 1000 Brussels, Belgium 2 Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, OD Taxonomy and Phylogeny (Ento- mology), Rue Vautierstraat 29, 1000 Brussels, Belgium 3 Laboratoire des Sciences de l’eau et environnement, Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Avenue Albert Thomas, 23, 87060 Limoges, France Corresponding author: Zoltán T. Nagy ([email protected]) Academic editor: K. Jordaens | Received 7 August 2013 | Accepted 27 November 2013 | Published 30 December 2013 Citation: Nagy ZT, Sonet G, Mortelmans J, Vandewynkel C, Grootaert P (2013) Using DNA barcodes for assessing diversity in the family Hybotidae (Diptera, Empidoidea). In: Nagy ZT, Backeljau T, De Meyer M, Jordaens K (Eds) DNA barcoding: a practical tool for fundamental and applied biodiversity research. ZooKeys 365: 263–278. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.365.6070 Abstract Empidoidea is one of the largest extant lineages of flies, but phylogenetic relationships among species of this group are poorly investigated and global diversity remains scarcely assessed. In this context, one of the most enigmatic empidoid families is Hybotidae. Within the framework of a pilot study, we barcoded 339 specimens of Old World hybotids belonging to 164 species and 22 genera (plus two Empis as outgroups) and attempted to evaluate whether patterns of intra- and interspecific divergences match the current tax- onomy. -

Biology 302-Systematic Botany

Biology 302 – Field Systematic Botany “Nomina si nescis, perit et cognitio rerum” (If you do not know the names of things, the knowledge of them is useless) Summer II 2013 Linneaus Critica Botanica 1737 Instructor Dr. Ross A. McCauley Office: 447 Berndt Hall Office phone: 970-247-7338 E-mail: [email protected] Webpage: http://faculty.fortlewis.edu/mccauley_r/index.html Office hours: MWR 10:00 am-12:10 pm and by appointment Course information Meeting time and place: Lecture/Lab MWR 8:00–10: 00 am, Berndt 440; Field T 8:00 am – 4:30 pm. The lab and herbarium will be open and available for independent work until at least noon on all class days. Required texts: Judd, W. S., C. S. Campbell, E. A. Kellogg, P. F. Stevens and M. J. Donoghue. 2008. Plant Systematics: A Phylogenetic Approach, 3rd Edition. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, MA. ISBN: 978-0-87893-407-2 Weber, W. A. and R. C. Wittmann. 2012. Colorado Flora: Western Slope, 4th edition. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, CO. ISBN: 978-1-60732-142-2 Harris, J. G. and M. W. Harris. 2001. Plant Identification Terminology, 2nd edition, Spring Lake Publishing, Spring Lake, UT. ISBN: 978-0-96402-216-4 Required Supplies (available at FLC bookstore – probably not shelved with textbooks – ask clerk for assistance) 10x handlens 1 Rite-in-the-Rain, Horizontal Line All-Weather Notebook, No. 391 Course Website: http://moodle.fortlewis.edu I will use Moodle as a repository for any lecture material and plant lists. Most of these will also be made available in class. -

R. P. LANE (Department of Entomology), British Museum (Natural History), London SW7 the Diptera of Lundy Have Been Poorly Studied in the Past

Swallow 3 Spotted Flytcatcher 28 *Jackdaw I Pied Flycatcher 5 Blue Tit I Dunnock 2 Wren 2 Meadow Pipit 10 Song Thrush 7 Pied Wagtail 4 Redwing 4 Woodchat Shrike 1 Blackbird 60 Red-backed Shrike 1 Stonechat 2 Starling 15 Redstart 7 Greenfinch 5 Black Redstart I Goldfinch 1 Robin I9 Linnet 8 Grasshopper Warbler 2 Chaffinch 47 Reed Warbler 1 House Sparrow 16 Sedge Warbler 14 *Jackdaw is new to the Lundy ringing list. RECOVERIES OF RINGED BIRDS Guillemot GM I9384 ringed 5.6.67 adult found dead Eastbourne 4.12.76. Guillemot GP 95566 ringed 29.6.73 pullus found dead Woolacombe, Devon 8.6.77 Starling XA 92903 ringed 20.8.76 found dead Werl, West Holtun, West Germany 7.10.77 Willow Warbler 836473 ringed 14.4.77 controlled Portland, Dorset 19.8.77 Linnet KC09559 ringed 20.9.76 controlled St Agnes, Scilly 20.4.77 RINGED STRANGERS ON LUNDY Manx Shearwater F.S 92490 ringed 4.9.74 pullus Skokholm, dead Lundy s. Light 13.5.77 Blackbird 3250.062 ringed 8.9.75 FG Eksel, Belgium, dead Lundy 16.1.77 Willow Warbler 993.086 ringed 19.4.76 adult Calf of Man controlled Lundy 6.4.77 THE DIPTERA (TWO-WINGED FLffiS) OF LUNDY ISLAND R. P. LANE (Department of Entomology), British Museum (Natural History), London SW7 The Diptera of Lundy have been poorly studied in the past. Therefore, it is hoped that the production of an annotated checklist, giving an indication of the habits and general distribution of the species recorded will encourage other entomologists to take an interest in the Diptera of Lundy. -

Anthecological Relations Reputedly Anemophilous Flowers and Syrphid

Ada Bot. Neerl. 25(3). June 1976, p. 205-211. Anthecological relations between reputedly anemophilous flowers and syrphid flies. II. Plantago media L. H. Leereveld A.D.J. Meeuse and P. Stelleman Hugo de Vries-laboratorium. Universiteit van Amsterdam SUMMARY After intensive field work in Upper Hessia (W. Germany) the authors have come to the con- clusion that although Plantago media L. is most probably visited much more frequently and wider of insects than P. lanceolata L.. flies of the by a range syrphid Melanostoma-Platychei- transfer rus group play a negligible role in the pollen of P. media. The possible reason for this unexpectedresult is anything but clear and only a tentative possibility is suggested. 1. INTRODUCTION After the relation between syrphid flies ofthe Melanostoma-Platycheirus (M P) been group and Plantago lanceolatahad studied in the Netherlands (Stelleman ofthis the role ofthese flies effective & Meeuse. part I series), possible syrphid as pollinators of other species of Plantago seemed a promising field of study. In the media, which to human to be particular species P. our senses appears more attractive than P. lanceolataboth optically and olfactorally, seemed a suitable p. object, the more so since a great many insect visitors have been recorded on media (see Knuth 1899and Kugler 1970). The opportunity arose when Professor Neubauerand Professor Weberling of the botanical institute of the University of Giessen invited us to study the pol- lination ecology of this species in the Giessen area. We arrived in the area when the flowering period of P. media had not reached its peak and stayed until in had been for some sites flowering was over or the grass mowed hay-making and the flowering spikes were cut off. -

Pollination Ecology Summary

Pollination Ecology Summary Prof. em. Klaus Ammann, Neuchâtel [email protected] June 2013 Ohne den Pollenübertragungs-Service blütenbesuchender Tiere könnten sich viele Blütenpanzen nicht geschlechtlich fortpanzen. Die komplexen und faszinierenden Bestäubungsvorgänge bei Blütenpanzen sind Ausdruck von Jahrmillionen von Selektionsvorgängen, verbunden mit Selbstorganisation der Lebewesen; eine Sicht, die auch Darwin schon unterstützte. Bei vielen zwischenartlichen Beziehungen haben sich zwei oder auch mehrere Arten in ihrer Entwicklung gegenseitig beeinusst. Man spricht hier von sogenannter Coevolution. Deutlich ist die Coevolution auch bei verschiedenen Bestäubungssystemen und -mechanismen, die von symbiontischer bis parasitischer Natur sein können. Die Art-Entstehung, die Vegetationsökologie und die Entstehung von Kulturpanzen sind eng damit verbunden Veranstalter: Naturforschende Gesellschaft Schaffhausen 1. Pollination Ecology Darwin http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pollination_syndrome http://www.cas.vanderbilt.edu/bioimages/pages/pollination.htm Fenster, C.B., Armbruster, W.S., Wilson, P., Dudash, M.R., & Thomson, J.D. (2004) Pollination syndromes and floral specialization. Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics, 35, pp 375-403 http://www.botanischergarten.ch/Pollination/Fenster-Pollination-Syndromes-2004.pdf invitation to browse in the website of the Friends of Charles Darwin http://darwin.gruts.com/weblog/archive/2008/02/ Working Place of Darwin in Downe Village http://www.focus.de/wissen/wissenschaft/wissenschaft-darwin-genoss-ein-suesses-studentenleben_aid_383172.html Darwin as a human being and as a scientist Darwin, C. (1862), On the various contrivances by which orchids are fertilized by insects and on the good effects of intercrossing The Complete Work of Charles Darwin online, Scanned, OCRed and corrected by John van Wyhe 2003; further corrections 8.2006. -

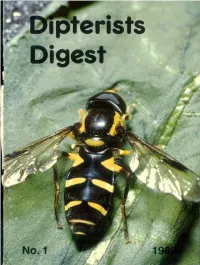

Ipterists Digest

ipterists Digest Dipterists’ Digest is a popular journal aimed primarily at field dipterists in the UK, Ireland and adjacent countries, with interests in recording, ecology, natural history, conservation and identification of British and NW European flies. Articles may be of any length up to 3000 words. Items exceeding this length may be serialised or printed in full, depending on the competition for space. They should be in clear concise English, preferably typed double spaced on one side of A4 paper. Only scientific names should be underlined- Tables should be on separate sheets. Figures drawn in clear black ink. about twice their printed size and lettered clearly. Enquiries about photographs and colour plates — please contact the Production Editor in advance as a charge may be made. References should follow the layout in this issue. Initially the scope of Dipterists' Digest will be:- — Observations of interesting behaviour, ecology, and natural history. — New and improved techniques (e.g. collecting, rearing etc.), — The conservation of flies and their habitats. — Provisional and interim reports from the Diptera Recording Schemes, including provisional and preliminary maps. — Records of new or scarce species for regions, counties, districts etc. — Local faunal accounts, field meeting results, and ‘holiday lists' with good ecological information/interpretation. — Notes on identification, additions, deletions and amendments to standard key works and checklists. — News of new publications/references/iiterature scan. Texts concerned with the Diptera of parts of continental Europe adjacent to the British Isles will also be considered for publication, if submitted in English. Dipterists Digest No.1 1988 E d ite d b y : Derek Whiteley Published by: Derek Whiteley - Sheffield - England for the Diptera Recording Scheme assisted by the Irish Wildlife Service ISSN 0953-7260 Printed by Higham Press Ltd., New Street, Shirland, Derby DE5 6BP s (0773) 832390. -

Empire State Native Pollinator Survey Study Plan

Empire State Native Pollinator Survey Study Plan i Empire State Native Pollinator Survey Study Plan June 2017 Matthew D. Schlesinger Erin L. White Jeffrey D. Corser Please cite this report as follows: Schlesinger, M.D., E.L. White, and J.D. Corser. 2017. Empire State Native pollinator survey study plan. New York Natural Heritage Program, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Albany, NY. Cover photos: Sanderson Bumble Bee (Bombus sandersoni) and flower longhorn (Clytus ruricola) by Larry Master, www.masterimages.org; Azalea sphinx moth (Darapsa choerilus) and Syrphus fly by Stephen Diehl and Vici Zaremba. ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Background: Rising Buzz and a Swarm of Pollinator Plans .................................................................... 1 Advisors and Taxonomic Experts .............................................................................................................. 1 Goal of the Survey ........................................................................................................................................ 2 General Sampling Design ............................................................................................................................. 2 The Role of Citizen Science ......................................................................................................................... 2 Focal Taxa .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Zootaxa, Empidoidea (Diptera)

ZOOTAXA 1180 The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera) BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR & JEFFREY M. CUMMING Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR & JEFFREY M. CUMMING The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera) (Zootaxa 1180) 172 pp.; 30 cm. 21 Apr. 2006 ISBN 1-877407-79-8 (paperback) ISBN 1-877407-80-1 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2006 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41383 Auckland 1030 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2006 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) Zootaxa 1180: 1–172 (2006) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1180 Copyright © 2006 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera) BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR1 & JEFFREY M. CUMMING2 1 Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Invertebrate Biodiversity, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, C.E.F., Ottawa, ON, Canada -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000).