P APERS of the I NTERNATIONAL C ONCERTINA a SSOCIATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 17-Tone Puzzle — and the Neo-Medieval Key That Unlocks It

The 17-tone Puzzle — And the Neo-medieval Key That Unlocks It by George Secor A Grave Misunderstanding The 17 division of the octave has to be one of the most misunderstood alternative tuning systems available to the microtonal experimenter. In comparison with divisions such as 19, 22, and 31, it has two major advantages: not only are its fifths better in tune, but it is also more manageable, considering its very reasonable number of tones per octave. A third advantage becomes apparent immediately upon hearing diatonic melodies played in it, one note at a time: 17 is wonderful for melody, outshining both the twelve-tone equal temperament (12-ET) and the Pythagorean tuning in this respect. The most serious problem becomes apparent when we discover that diatonic harmony in this system sounds highly dissonant, considerably more so than is the case with either 12-ET or the Pythagorean tuning, on which we were hoping to improve. Without any further thought, most experimenters thus consign the 17-tone system to the discard pile, confident in the knowledge that there are, after all, much better alternatives available. My own thinking about 17 started in exactly this way. In 1976, having been a microtonal experimenter for thirteen years, I went on record, dismissing 17-ET in only a couple of sentences: The 17-tone equal temperament is of questionable harmonic utility. If you try it, I doubt you’ll stay with it for long.1 Since that time I have become aware of some things which have caused me to change my opinion completely. -

Download the Just Intonation Primer

THE JUST INTONATION PPRIRIMMEERR An introduction to the theory and practice of Just Intonation by David B. Doty Uncommon Practice — a CD of original music in Just Intonation by David B. Doty This CD contains seven compositions in Just Intonation in diverse styles — ranging from short “fractured pop tunes” to extended orchestral movements — realized by means of MIDI technology. My principal objectives in creating this music were twofold: to explore some of the novel possibilities offered by Just Intonation and to make emotionally and intellectually satisfying music. I believe I have achieved both of these goals to a significant degree. ——David B. Doty The selections on this CD process—about synthesis, decisions. This is definitely detected in certain struc- were composed between sampling, and MIDI, about not experimental music, in tures and styles of elabora- approximately 1984 and Just Intonation, and about the Cageian sense—I am tion. More prominent are 1995 and recorded in 1998. what compositional styles more interested in result styles of polyphony from the All of them use some form and techniques are suited (aesthetic response) than Western European Middle of Just Intonation. This to various just tunings. process. Ages and Renaissance, method of tuning is com- Taken collectively, there It is tonal music (with a garage rock from the 1960s, mendable for its inherent is no conventional name lowercase t), music in which Balkan instrumental dance beauty, its variety, and its for the music that resulted hierarchic relations of tones music, the ancient Japanese long history (it is as old from this process, other are important and in which court music gagaku, Greek as civilization). -

A Study of Microtones in Pop Music

University of Huddersfield Repository Chadwin, Daniel James Applying microtonality to pop songwriting: A study of microtones in pop music Original Citation Chadwin, Daniel James (2019) Applying microtonality to pop songwriting: A study of microtones in pop music. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34977/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Applying microtonality to pop songwriting A study of microtones in pop music Daniel James Chadwin Student number: 1568815 A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Huddersfield May 2019 1 Abstract While temperament and expanded tunings have not been widely adopted by pop and rock musicians historically speaking, there has recently been an increased interest in microtones from modern artists and in online discussion. -

Mto.95.1.4.Cuciurean

Volume 1, Number 4, July 1995 Copyright © 1995 Society for Music Theory John D. Cuciurean KEYWORDS: scale, interval, equal temperament, mean-tone temperament, Pythagorean tuning, group theory, diatonic scale, music cognition ABSTRACT: In Mathematical Models of Musical Scales, Mark Lindley and Ronald Turner-Smith attempt to model scales by rejecting traditional Pythagorean ideas and applying modern algebraic techniques of group theory. In a recent MTO collaboration, the same authors summarize their work with less emphasis on the mathematical apparatus. This review complements that article, discussing sections of the book the article ignores and examining unique aspects of their models. [1] From the earliest known music-theoretical writings of the ancient Greeks, mathematics has played a crucial role in the development of our understanding of the mechanics of music. Mathematics not only proves useful as a tool for defining the physical characteristics of sound, but abstractly underlies many of the current methods of analysis. Following Pythagorean models, theorists from the middle ages to the present day who are concerned with intonation and tuning use proportions and ratios as the primary language in their music-theoretic discourse. However, few theorists in dealing with scales have incorporated abstract algebraic concepts in as systematic a manner as the recent collaboration between music scholar Mark Lindley and mathematician Ronald Turner-Smith.(1) In their new treatise, Mathematical Models of Musical Scales: A New Approach, the authors “reject the ancient Pythagorean idea that music somehow &lsquois’ number, and . show how to design mathematical models for musical scales and systems according to some more modern principles” (7). -

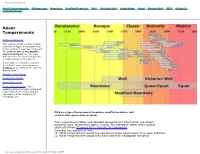

Temperaments Visualized

Temperaments Visualized About Temperaments • Pythagorean • Meantone • Modified Meantone • Well • Victorian Well • Quasi-Equal • Equal • Modern Well • EBVT • Return to rollingball home About Temperaments Historical Overview This section contains a brief graphic overview of types of temperaments in the context of classical composers. The bottom half of the graphic has live hotspots, but the upper half (with the names of composers) is sadly lacking in interactivity. If you click on a miniature and get the full-size chart, you can press backspace to return to the current History image. Homage to Jorgensen Reading the Charts About "Key Color" Temperamental links - other websites sites of interest will appear in the frame to the right, and you can explore while remaining at rollingball.com... Click on a type of temperament (meantone, modified meantone, well, victorian well, quasi-equal, or equal). The temperament dates and detailed temperament information are drawn primarily from Jorgensen's tome, Tuning. The composer dates were quickly abstracted from Classical Net's Timeline of Composers. Consider two aspects of this: (1) What temperament would the composers have heard when they were children? (2) What temperament would they have had their keyboards tuned to? http://www.rollingball.com/TemperamentsFrames.htm10/2/2006 4:13:04 PM About Temperaments About Temperaments Historical Overview This section contains a brief graphic overview of types of temperaments in the context of classical composers. The bottom half of the graphic has live hotspots, but the upper half (with the names of composers) is sadly lacking in interactivity. If you click on a miniature and get the full-size chart, you can press backspace to return to the current History image. -

European Philosophy and the Triumph of Equal Temperament/ Noel David Hudson University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2007 Abandoning nature :: European philosophy and the triumph of equal temperament/ Noel David Hudson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Hudson, Noel David, "Abandoning nature :: European philosophy and the triumph of equal temperament/" (2007). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1628. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1628 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABANDONING NATURE: EUROPEAN PHILOSOPHY AND THE TRIUMPH OF EQUAL TEMPERAMENT A Thesis Presented by NOEL DAVID HUDSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2007 UMASS/Five College Graduate Program in History © Copyright by Noel David Hudson 2006 All Rights Reserved ABANDONING NATURE: EUROPEAN PHILOSOPHY AND THE TRIUMPH OF EQUAL TEMPERAMENT A Thesis Presented by NOEL DAVID HUDSON Approved as to style and content by: Daniel Gordon, th^ir Bruce Laurie, Member Brian Ogilvie, Member Audrey Altstadt, Department Head Department of History CONTKNTS ( HAPTER Page 1. [NTR0D1 f< i ion 2. what is TEMPERAMENT? 3. THE CLASSICAL LEGACY 4. THE ENGLISH, MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS, AND OTHER PROBLEMS 5. A TROUBLING SOLUTION (>. ANCIEN1 HABITS OF MUSICAL THOUGHT IN THE "NEW PHILOSOPHY" 7. FROM THEORY TO PRACTICE X. A THEORETICAL INTERLUDE 9. -

Lute Tuning and Temperament in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

LUTE TUNING AND TEMPERAMENT IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES BY ADAM WEAD Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University August, 2014 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. Nigel North, Research Director & Chair Stanley Ritchie Ayana Smith Elisabeth Wright ii Contents Acknowledgments . v Introduction . 1 1 Tuning and Temperament 5 1.1 The Greeks’ Debate . 7 1.2 Temperament . 14 1.2.1 Regular Meantone and Irregular Temperaments . 16 1.2.2 Equal Division . 19 1.2.3 Equal Temperament . 25 1.3 Describing Temperaments . 29 2 Lute Fretting Systems 32 2.1 Pythagorean Tunings for Lute . 33 2.2 Gerle’s Fretting Instructions . 37 2.3 John Dowland’s Fretting Instructions . 46 2.4 Ganassi’s Regola Rubertina .......................... 53 2.4.1 Ganassi’s Non-Pythagorean Frets . 55 2.5 Spanish Vihuela Sources . 61 iii 2.6 Sources of Equal Fretting . 67 2.7 Summary . 71 3 Modern Lute Fretting 74 3.1 The Lute in Ensembles . 76 3.2 The Theorbo . 83 3.2.1 Solutions Utilizing Re-entrant Tuning . 86 3.2.2 Tastini . 89 3.2.3 Other Solutions . 95 3.3 Meantone Fretting in Tablature Sources . 98 4 Summary of Solutions 105 4.1 Frets with Fixed Semitones . 106 4.2 Enharmonic Fretting . 110 4.3 Playing with Ensembles . 113 4.4 Conclusion . 118 A Complete Fretting Diagrams 121 B Fret Placement Guide 124 C Calculations 127 C.1 Hans Gerle . -

Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder

Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2010 ABSTRACT Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder In this paper, I describe my recent work, which is primarily focused around a dynamic tuning system, and the construction of new electro-acoustic instruments using this system. I provide an overview of my aesthetic and theoretical influences, in order to give some idea of the path that led me to my current project. I then explain the tuning system itself, which is a type of dynamically tuned just intonation, realized through electronics. The third section of this paper gives details on the design and construction of the instruments I have invented for my own compositional purposes. The final section of this paper gives an analysis of the first large-scale piece to be written for my instruments using my tuning system, Concerning the Nature of Things. Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder I. Why Adaptable Just Intonation on Invented Instruments? 1.1 - Influences 1.1.1 - Inspiration from Medieval and Renaissance music 1.1.2 - Inspiration from Harry Partch 1.1.3 - Inspiration from American country music 1.2 - Tuning systems 1.2.1 - Why just? 1.2.1.1 – Non-prescriptive pitch systems 1.2.1.2 – Just pitch systems 1.2.1.3 – Tempered pitch systems 1.2.1.4 – Rationale for choice of Just tunings 1.2.1.4.1 – Consideration of non-prescriptive -

Musical Tuning Systems As a Form of Expression

Musical Tuning Systems as a Form of Expression Project Team: Lewis Cook [email protected] Benjamin M’Sadoques [email protected] Project Advisor Professor Wilson Wong Department of Computer Science This report represents the work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its website without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, please see http://www.wpi.edu/academics/ugradstudies/project- learning.html Abstract Many cultures and time periods throughout history have used a myriad of different practices to tune their instruments, perform, and create music. However, most musicians in the western world will only experience 12-tone equal temperament a represented by the keys on a piano. We want musicians to recognize that choosing a tuning system is a form of musical expression. The goal of this project was to help musicians of any skill-level experience, perform, and create music involving tuning systems. We created software to allow musicians to experiment and implement alternative tuning systems into their own music. ii Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................... ii Table of Figures .................................................................................................................... vii 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

Tuning Presets in the MOTM

Tuning Presets in the Sequential Prophet X Compiled by Robert Rich, September 2018 Comments for tunings 17-65 derived from the Scala library. Many thanks to Max Magic Microtuner for conversion assistance. R. Rich Notes: All of the presets except for #1 (12 Tone Equal Temperament) can be over-written by sending a tuning in the MTS format (Midi Tuning Standard.) The presets #2-17 match the Prophet 12, P6 and OB6, and began as a selection I made for the Synthesis Technology MOTM 650 Midi-CV module. Actual program numbers within the MTS messages start at #0 for the built-in 12ET, #1-64 for the user tunings. The display shows these as #2-65, with 12ET as #1. I intend these tunings only as an introduction, and I did not research their historical accuracy. For convenience, I used the software’s default 1/1 of C4 (Midi note 60), although this is not the original 1/1 for some of the tunings shown. Some of these tunings come very close to standard 12ET, and some of them are downright wacky, sometimes specific to a particular composer or piece of music. The tunings from 18 to 65 are organized only by alphabet, culled from the Scala library, not in any logical order. 1. 12 Tone Equal Temperament (non-erasable) The default Western tuning, based on the twelfth root of two. Good fourths and fifths, horrible thirds and sixths. 2. Harmonic Series MIDI notes 36-95 reflect harmonics 2 through 60 based on the fundamental of A = 27.5 Hz. -

Invariance of Controller Fingerings Across a Continuum of Tunings

Invariance of Controller Fingerings across a Continuum of Tunings Andrew Milne∗∗, William Setharesyy, and James Plamondonzz May 26, 2007 Introduction On the standard piano-style keyboard, intervals and chords have different shapes in each key. For example, the geometric pattern of the major third C–E is different from the geometric pattern of the major third D–F]. Similarly, the major scale is fingered differently in each of the twelve keys (in this usage, fingerings are specified without regard to which digits of the hand press which keys). Other playing surfaces, such as the keyboards of [Bosanquet, 1877] and [Wicki, 1896], have the property that each interval, chord, and scale type have the same geometric shape in every key. Such keyboards are said to be transpositionally invariant [Keisler, 1988]. There are many possible ways to tune musical intervals and scales, and the introduction of computer and software synthesizers makes it possible to realize any sound in any tuning [Carlos, 1987]. Typically, however, keyboard controllers are designed to play in a single tuning, such as the familiar 12-tone equal temperament (12-TET) which divides the octave into twelve perceptually equal pieces. Is it possible to create a keyboard surface that is capable of supporting many possible tunings? Is it possible to do so in a way that analogous musical intervals are fingered the same throughout the various tunings, so that (for example) the 12-TET fifth is fingered the same as the Just fifth and as the 17-TET fifth? (Just tunings ∗∗Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] yyDepartment of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706 USA. -

MTO 12.3: Duffin, Just Intonation in Renaissance Theory and Practice

Volume 12, Number 3, October 2006 Copyright © 2006 Society for Music Theory Ross W. Duffin ABSTRACT: Just intonation has a reputation as a chimerical, theoretical system that simply cannot work in practice. This is based on the assessment of most modern authorities and supported by misgivings expressed during the Renaissance when the practice was supposedly at its height. Looming large among such misgivings are tuning puzzles printed by the 16th-century mathematician, Giovanni Battista Benedetti. However, Renaissance music theorists are so unanimous in advocating the simple acoustical ratios of Just intonation that it seems clear that some reconciliation must have occurred between the theory and practice of it. This article explores the basic theory of Just intonation as well as problematic passages used to deny its practicability, and proposes solutions that attempt to satisfy both the theory and the ear. Ultimately, a resource is offered to help modern performers approach this valuable art. Received June 2006 Introduction | Theoretical Background | Benedetti's Puzzles | Problematic Passages | Is Just Tuning Possible? A New Approach | Problem Spots in the Exercises | Rehearsal Usage | Conclusion Introduction The idea . that one can understand the ratios of musical consonances without experiencing them with the senses is wrong. Nor can one know the theory of music without being versed in its practice. [1] So begins the first of two letters sent by the mathematician Giovanni Battista Benedetti to the composer Cipriano de Rore in 1563. Subsequently publishing the letters in 1585,(1) Benedetti was attempting to demonstrate that adhering to principles of Just intonation, as championed most famously by Gioseffo Zarlino,(2) would, in certain cases, cause the pitch of the ensemble to migrate.