Kali Malone Harmonic Space & Hegemonic Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freier Download BA 99 Als

BAD 99 ALCHEMY »Was bleibt einem denn anderes übrig, als zu viel in die Dinge hineinzuinterpretieren?«, sagte P. leichthin. »In was für einer armen, oberflächlichen, langweiligen Welt würden wir leben, wenn wir das nicht täten? Außerdem: Ist das überhaupt möglich? Es gibt immer mehr Bedeutungen, als wir erfassen können.« Edward St Auby Lesestoff (gefunden auf Flohmärkten, Krabbeltischen, bei Oxfam oder Brauchbar ) Gabrielle Bell - Die Voyeure Sergio Bleda - Schlaf, kleines Mädchen; Blutiger Winter Charles Bukowski - Anmerkungen eines Dirty Old Man; Fucktotum; Das ausbruchsichere Paradies Michael Cho - Shoplifter Hugo Claus - Der Kummer von Flandern Daniel Clowes - Ghost World Guido Crepax & R. L. Stevenson - Dr. Jekyll und Mr. Hyde Glyn Dillon - Das Nao in Brown Franz Dobler - Aufräumen Willem Elsschot - Villa des Roses Hans Fallada - Bauern, Bonzen und Bomben Theodor Fontane - Frau Jenny Treibel; Unterm Birnbaum Christophe Gaultier - Das Phantom der Oper (nach Gaston Leroux) Karl-Markus Gauß - Die Hundeesser von Svinia Georgi Gospodinov - Physik der Schwermut Günter Grass - Ein weites Feld Jiří Gruša - Der 16. Fragebogen Jung [Henin] - Kwaidan Franz Kafka - Der Bau Maurizio Maggiani - Königin ohne Schmuck Ransom Riggs + Cassandra Jean - Die Insel... Die Stadt der besonderen Kinder Per Petterson - Pferde stehlen Joann Sfar - Pascin Edward St Aubyn - Muttermilch Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa - Der Gattopardo Guntram Vesper - Frohburg Bernhard Viel - Utopie der Nation Dieter Wellershoff - Der Ernstfall Ror Wolf - Punkt ist Punkt; Die heiße Luft der Spiele Vladimir Zarev - Verfall 2 Alsarah & The Nubatones Wir strahlen, am 1.6.2018 beim Africa Festival goldberauscht durch ALSARAH & THE NUBATONES. Durch Sarah Mohamed Abunama-Elgadi, kurz: Alsarah, und ihre schöne Schwester Nahid, die man sich beide als Abgesandte aus dem Goldland der Ägypter reiz- voller nicht vorstellen kann. -

The 17-Tone Puzzle — and the Neo-Medieval Key That Unlocks It

The 17-tone Puzzle — And the Neo-medieval Key That Unlocks It by George Secor A Grave Misunderstanding The 17 division of the octave has to be one of the most misunderstood alternative tuning systems available to the microtonal experimenter. In comparison with divisions such as 19, 22, and 31, it has two major advantages: not only are its fifths better in tune, but it is also more manageable, considering its very reasonable number of tones per octave. A third advantage becomes apparent immediately upon hearing diatonic melodies played in it, one note at a time: 17 is wonderful for melody, outshining both the twelve-tone equal temperament (12-ET) and the Pythagorean tuning in this respect. The most serious problem becomes apparent when we discover that diatonic harmony in this system sounds highly dissonant, considerably more so than is the case with either 12-ET or the Pythagorean tuning, on which we were hoping to improve. Without any further thought, most experimenters thus consign the 17-tone system to the discard pile, confident in the knowledge that there are, after all, much better alternatives available. My own thinking about 17 started in exactly this way. In 1976, having been a microtonal experimenter for thirteen years, I went on record, dismissing 17-ET in only a couple of sentences: The 17-tone equal temperament is of questionable harmonic utility. If you try it, I doubt you’ll stay with it for long.1 Since that time I have become aware of some things which have caused me to change my opinion completely. -

Download the Just Intonation Primer

THE JUST INTONATION PPRIRIMMEERR An introduction to the theory and practice of Just Intonation by David B. Doty Uncommon Practice — a CD of original music in Just Intonation by David B. Doty This CD contains seven compositions in Just Intonation in diverse styles — ranging from short “fractured pop tunes” to extended orchestral movements — realized by means of MIDI technology. My principal objectives in creating this music were twofold: to explore some of the novel possibilities offered by Just Intonation and to make emotionally and intellectually satisfying music. I believe I have achieved both of these goals to a significant degree. ——David B. Doty The selections on this CD process—about synthesis, decisions. This is definitely detected in certain struc- were composed between sampling, and MIDI, about not experimental music, in tures and styles of elabora- approximately 1984 and Just Intonation, and about the Cageian sense—I am tion. More prominent are 1995 and recorded in 1998. what compositional styles more interested in result styles of polyphony from the All of them use some form and techniques are suited (aesthetic response) than Western European Middle of Just Intonation. This to various just tunings. process. Ages and Renaissance, method of tuning is com- Taken collectively, there It is tonal music (with a garage rock from the 1960s, mendable for its inherent is no conventional name lowercase t), music in which Balkan instrumental dance beauty, its variety, and its for the music that resulted hierarchic relations of tones music, the ancient Japanese long history (it is as old from this process, other are important and in which court music gagaku, Greek as civilization). -

Andrián Pertout

Andrián Pertout Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition Volume 1 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Produced on acid-free paper Faculty of Music The University of Melbourne March, 2007 Abstract Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition encompasses the work undertaken by Lou Harrison (widely regarded as one of America’s most influential and original composers) with regards to just intonation, and tuning and scale systems from around the globe – also taking into account the influential work of Alain Daniélou (Introduction to the Study of Musical Scales), Harry Partch (Genesis of a Music), and Ben Johnston (Scalar Order as a Compositional Resource). The essence of the project being to reveal the compositional applications of a selection of Persian, Indonesian, and Japanese musical scales utilized in three very distinct systems: theory versus performance practice and the ‘Scale of Fifths’, or cyclic division of the octave; the equally-tempered division of the octave; and the ‘Scale of Proportions’, or harmonic division of the octave championed by Harrison, among others – outlining their theoretical and aesthetic rationale, as well as their historical foundations. The project begins with the creation of three new microtonal works tailored to address some of the compositional issues of each system, and ending with an articulated exposition; obtained via the investigation of written sources, disclosure -

A Study of Microtones in Pop Music

University of Huddersfield Repository Chadwin, Daniel James Applying microtonality to pop songwriting: A study of microtones in pop music Original Citation Chadwin, Daniel James (2019) Applying microtonality to pop songwriting: A study of microtones in pop music. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34977/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Applying microtonality to pop songwriting A study of microtones in pop music Daniel James Chadwin Student number: 1568815 A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Huddersfield May 2019 1 Abstract While temperament and expanded tunings have not been widely adopted by pop and rock musicians historically speaking, there has recently been an increased interest in microtones from modern artists and in online discussion. -

Mto.95.1.4.Cuciurean

Volume 1, Number 4, July 1995 Copyright © 1995 Society for Music Theory John D. Cuciurean KEYWORDS: scale, interval, equal temperament, mean-tone temperament, Pythagorean tuning, group theory, diatonic scale, music cognition ABSTRACT: In Mathematical Models of Musical Scales, Mark Lindley and Ronald Turner-Smith attempt to model scales by rejecting traditional Pythagorean ideas and applying modern algebraic techniques of group theory. In a recent MTO collaboration, the same authors summarize their work with less emphasis on the mathematical apparatus. This review complements that article, discussing sections of the book the article ignores and examining unique aspects of their models. [1] From the earliest known music-theoretical writings of the ancient Greeks, mathematics has played a crucial role in the development of our understanding of the mechanics of music. Mathematics not only proves useful as a tool for defining the physical characteristics of sound, but abstractly underlies many of the current methods of analysis. Following Pythagorean models, theorists from the middle ages to the present day who are concerned with intonation and tuning use proportions and ratios as the primary language in their music-theoretic discourse. However, few theorists in dealing with scales have incorporated abstract algebraic concepts in as systematic a manner as the recent collaboration between music scholar Mark Lindley and mathematician Ronald Turner-Smith.(1) In their new treatise, Mathematical Models of Musical Scales: A New Approach, the authors “reject the ancient Pythagorean idea that music somehow &lsquois’ number, and . show how to design mathematical models for musical scales and systems according to some more modern principles” (7). -

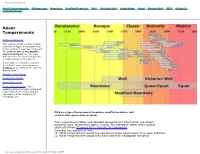

Temperaments Visualized

Temperaments Visualized About Temperaments • Pythagorean • Meantone • Modified Meantone • Well • Victorian Well • Quasi-Equal • Equal • Modern Well • EBVT • Return to rollingball home About Temperaments Historical Overview This section contains a brief graphic overview of types of temperaments in the context of classical composers. The bottom half of the graphic has live hotspots, but the upper half (with the names of composers) is sadly lacking in interactivity. If you click on a miniature and get the full-size chart, you can press backspace to return to the current History image. Homage to Jorgensen Reading the Charts About "Key Color" Temperamental links - other websites sites of interest will appear in the frame to the right, and you can explore while remaining at rollingball.com... Click on a type of temperament (meantone, modified meantone, well, victorian well, quasi-equal, or equal). The temperament dates and detailed temperament information are drawn primarily from Jorgensen's tome, Tuning. The composer dates were quickly abstracted from Classical Net's Timeline of Composers. Consider two aspects of this: (1) What temperament would the composers have heard when they were children? (2) What temperament would they have had their keyboards tuned to? http://www.rollingball.com/TemperamentsFrames.htm10/2/2006 4:13:04 PM About Temperaments About Temperaments Historical Overview This section contains a brief graphic overview of types of temperaments in the context of classical composers. The bottom half of the graphic has live hotspots, but the upper half (with the names of composers) is sadly lacking in interactivity. If you click on a miniature and get the full-size chart, you can press backspace to return to the current History image. -

European Philosophy and the Triumph of Equal Temperament/ Noel David Hudson University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2007 Abandoning nature :: European philosophy and the triumph of equal temperament/ Noel David Hudson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Hudson, Noel David, "Abandoning nature :: European philosophy and the triumph of equal temperament/" (2007). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1628. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1628 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABANDONING NATURE: EUROPEAN PHILOSOPHY AND THE TRIUMPH OF EQUAL TEMPERAMENT A Thesis Presented by NOEL DAVID HUDSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2007 UMASS/Five College Graduate Program in History © Copyright by Noel David Hudson 2006 All Rights Reserved ABANDONING NATURE: EUROPEAN PHILOSOPHY AND THE TRIUMPH OF EQUAL TEMPERAMENT A Thesis Presented by NOEL DAVID HUDSON Approved as to style and content by: Daniel Gordon, th^ir Bruce Laurie, Member Brian Ogilvie, Member Audrey Altstadt, Department Head Department of History CONTKNTS ( HAPTER Page 1. [NTR0D1 f< i ion 2. what is TEMPERAMENT? 3. THE CLASSICAL LEGACY 4. THE ENGLISH, MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS, AND OTHER PROBLEMS 5. A TROUBLING SOLUTION (>. ANCIEN1 HABITS OF MUSICAL THOUGHT IN THE "NEW PHILOSOPHY" 7. FROM THEORY TO PRACTICE X. A THEORETICAL INTERLUDE 9. -

Lute Tuning and Temperament in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

LUTE TUNING AND TEMPERAMENT IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES BY ADAM WEAD Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University August, 2014 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. Nigel North, Research Director & Chair Stanley Ritchie Ayana Smith Elisabeth Wright ii Contents Acknowledgments . v Introduction . 1 1 Tuning and Temperament 5 1.1 The Greeks’ Debate . 7 1.2 Temperament . 14 1.2.1 Regular Meantone and Irregular Temperaments . 16 1.2.2 Equal Division . 19 1.2.3 Equal Temperament . 25 1.3 Describing Temperaments . 29 2 Lute Fretting Systems 32 2.1 Pythagorean Tunings for Lute . 33 2.2 Gerle’s Fretting Instructions . 37 2.3 John Dowland’s Fretting Instructions . 46 2.4 Ganassi’s Regola Rubertina .......................... 53 2.4.1 Ganassi’s Non-Pythagorean Frets . 55 2.5 Spanish Vihuela Sources . 61 iii 2.6 Sources of Equal Fretting . 67 2.7 Summary . 71 3 Modern Lute Fretting 74 3.1 The Lute in Ensembles . 76 3.2 The Theorbo . 83 3.2.1 Solutions Utilizing Re-entrant Tuning . 86 3.2.2 Tastini . 89 3.2.3 Other Solutions . 95 3.3 Meantone Fretting in Tablature Sources . 98 4 Summary of Solutions 105 4.1 Frets with Fixed Semitones . 106 4.2 Enharmonic Fretting . 110 4.3 Playing with Ensembles . 113 4.4 Conclusion . 118 A Complete Fretting Diagrams 121 B Fret Placement Guide 124 C Calculations 127 C.1 Hans Gerle . -

Hcmf.Co.Uk Box Office 01484 430528 #Hcmf2019 Friday 15 – Sunday 24

Friday 15 – Sunday 24 November 2019 hcmf.co.uk Box Office 01484 430528 #hcmf2019 UK UK PREMIERE FESTIVAL DIARY W WORLD PREMIERE DATE NO EVENT TIME VENUE Fri 15 Nov Exhibition Launch: Claudia Molitor W 4pm Market Gallery, Temporary Contemporary, Queensgate Market edges ensemble: Grapefruit 5pm Temporary Contemporary, Queensgate Market Pre-Concert Talk: Naomi Pinnock + Ann Cleare 6pm St Paul’s Hall 1 Sonar Quartett + Juliet Fraser W UK 7pm St Paul’s Hall 2 The Riot Ensemble: Ann Cleare Portrait UK 9.30pm Huddersfield Town Hall Hanna Hartman: Solo Works UK 11.15pm Bates Mill Photographic Studio Sat 16 Nov Mini Pop-Up Art School 10am - 12pm Temporary Contemporary Queensgate Market Meet the Composer: Hanna Hartman 11am Phipps Hall 3 Ellen Arkbro + Marcus Pal W 1pm St Paul’s Hall 4 Iced Bodies UK 4pm Bates Mill Blending Shed 5 The Riot Ensemble W UK 7pm St Paul’s Hall 6 Decay / Sofia Jernberg 9.45pm Bates Mill Photographic Studio Sun 17 Nov Meet the Composer: Heiner Goebbels 11am Phipps Hall 7 Norrbotten NEO UK 1pm St Paul’s Hall 8 Hanna Hartman: Hurricane Season W 5pm Bates Mill Photographic Studio 9 Jenny Hval: The Practice Of Love 7pm Bates Mill Blending Shed 10 Heiner Goebbels + Gianni Gebbia 9pm St Paul’s Hall Isidore Isou: Juvenal Symphony No 4 UK 11pm Huddersfield Town Hall Mon 18 Nov Launch Event: cageconcert 10am - 5pm Richard Steinitz Building Atrium Installation: Georgia Rodgers W 11am - 5pm SPIRAL Studio, Richard Steinitz Building Group Chat W 11.30am Richard Steinitz Building Atrium John Butcher W 12pm Phipps Hall The Hermes Experiment -

Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder

Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2010 ABSTRACT Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder In this paper, I describe my recent work, which is primarily focused around a dynamic tuning system, and the construction of new electro-acoustic instruments using this system. I provide an overview of my aesthetic and theoretical influences, in order to give some idea of the path that led me to my current project. I then explain the tuning system itself, which is a type of dynamically tuned just intonation, realized through electronics. The third section of this paper gives details on the design and construction of the instruments I have invented for my own compositional purposes. The final section of this paper gives an analysis of the first large-scale piece to be written for my instruments using my tuning system, Concerning the Nature of Things. Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder I. Why Adaptable Just Intonation on Invented Instruments? 1.1 - Influences 1.1.1 - Inspiration from Medieval and Renaissance music 1.1.2 - Inspiration from Harry Partch 1.1.3 - Inspiration from American country music 1.2 - Tuning systems 1.2.1 - Why just? 1.2.1.1 – Non-prescriptive pitch systems 1.2.1.2 – Just pitch systems 1.2.1.3 – Tempered pitch systems 1.2.1.4 – Rationale for choice of Just tunings 1.2.1.4.1 – Consideration of non-prescriptive -

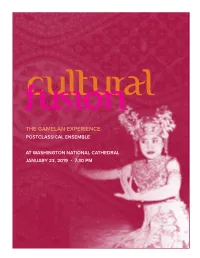

The Gamelan Experience Postclassical Ensemble

fusioncultural THE GAMELAN EXPERIENCE POSTCLASSICAL ENSEMBLE AT WASHINGTON NATIONAL CATHEDRAL JANUARY 23, 2019 • 7:30 PM Tonight’s performance is presented in partnership with Ambassador Budi Bowoleksono and the Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia. Underwriting is provided by The DC Commission on the Arts & Humanities, The Morris & Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation, Bloomberg Phanthropics and Freeport-McMoRan. fusioncultural THE GAMELAN EXPERIENCE POSTCLASSICAL ENSEMBLE AT WASHINGTON NATIONAL CATHEDRAL JANUARY 23, 2019 • 7:30 PM BENJAMIN PASTERNACK & WAN-CHI SU, piano NETANEL DRAIBLATE violin THE INDONESIAN EMBASSY JAVANESE GAMELAN, PAK MURYANTO, director THE INDONESIAN EMBASSY BALINESE GAMELAN, I. NYOMAN SUADIN, director PostClassical Ensemble conducted by ANGEL GIL-ORDÓÑEZ hosted & produced by JOSEPH HOROWITZ additional commentary INDONESIAN AMBASSADOR BUDI BOWOLEKSONO GAMELAN SCHOLAR BILL ALVES PROGRAM Javanese Gamelan: Sesonderan; Peacock Dance Claude Debussy: Pagodes (1903) Wan-Chi Su Maurice Ravel: La vallée des cloches (1905) Benjamin Pasternack Balinese Gamelan: Taboeh teloe Colin McPhee: Balinese Ceremonial Music for two pianos (1938) Taboeh teloe Pemoengkah Olivier Messiaen: Visions de l’Amen, movement one (1943) Amen de la Création Francis Poulenc: Sonata for Two Pianos, movement one (1953) Prologue: Extrêmement lent et calme Bill Alves: Black Toccata (2007; D.C. premiere) Wan-Chi Su & Benjamin Pasternack Intermission performance: Balinese Gamelan with Dancers Puspanjali Topeng Tua (composed by I. Nyoman Windha) Margapati (depicting