Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded From: Version: Published Version Publisher: Visit Manchester

Lindfield, Peter (2020) Building a Civic Gothic Palace for Britain’s Cotton Em- pire: the architecture of Manchester Town Hall. Visit Manchester. Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/626278/ Version: Published Version Publisher: Visit Manchester Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk Building a Civic Gothic Palace for Britain’s Cotton Empire: the architecture of Manchester Town Hall - Visit Manchester 01/08/2020, 16:50 Map Tickets Buy the Guide on Jul 29 2020 Building a Civic Gothic Palace for Britain’s Cotton Empire: the architecture of Manchester Town Hall In Haunt The twenty-third instalment as part of an ongoing series for Haunt Manchester by Dr Peter N. Lindfield FSA,FSA, exploring Greater Manchester’s Gothic architecture and hidden heritage. Peter’s previous Haunt Manchester articles include features on Ordsall Hall,, Albert’s Schloss and Albert Hall,, thethe MancunianMancunian GothicGothic SundaySunday SchoolSchool of St Matthew’s,, Arlington House inin Salford,Salford, MinshullMinshull StreetStreet CityCity PolicePolice andand SessionSession CourtsCourts and their furniture,, Moving Manchester's Shambles,, Manchester’s Modern Gothic in St Peter’s Square,, whatwhat was St John’s Church,, Manchester Cathedral,, The Great Hall at The University of Manchester,, St Chad’s inin Rochdale and more. From the city’s striking Gothic features to the more unusual aspects of buildings usually taken for granted and history hidden in plain sight, a variety of locations will be explored and visited over the course of 2020. His video series on Gothic Manchester can be viewed here.. InIn thisthis articlearticle hehe considersconsiders oneone ofof Manchester’sManchester’s landmarklandmark GothicGothic buildings,buildings, ManchesterManchester TownTown Hall,Hall, whichwhich isis currently undergoing restoration work (see(see below).below). -

3. Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

• Of course, their patrons, largely the middle-class themselves form different groups and each member of the PRB appealed to different types of buyers but together they created a stronger brand. In fact, they differed from a boy band as they created works that were bought independently. As well as their overall PRB brand each created an individual brand (sub-cognitive branding) that convinced the buyer they were making a wise investment. • Millais could be trusted as he was a born artist, an honest Englishman and made an ARA in 1853 and later RA (and President just before he died). • Hunt could be trusted as an investment as he was serious, had religious convictions and worked hard at everything he did. • Rossetti was a typical unreliable Romantic image of the artist so buying one of his paintings was a wise investment as you were buying the work of a ‘real artist’. 1 • The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) had only seven members but influenced many other artists. • Those most closely associated with the PRB were Ford Madox Brown (who was seven years older), Elizabeth Siddal (who died in 1862) and Walter Deverell (who died in 1854). • Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris were about five years younger. They met at Oxford and were influenced by Rossetti. I will discuss them more fully when I cover the Arts & Crafts Movement. • There were many other artists influenced by the PRB including, • John Brett, who was influenced by John Ruskin, • Arthur Hughes, a successful artist best known for April Love, • Henry Wallis, an artist who is best known for The Death of Chatterton (1856) and The Stonebreaker (1858), • William Dyce, who influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and whose Pegwell Bay is untypical but the most Pre-Raphaelite in style of his works. -

Renaissance to Regent Street: Harold Rathbone and the Della Robbia Pottery of Birkenhead

RENAISSANCE TO REGENT STREET: HAROLD RATHBONE AND THE DELLA ROBBIA POTTERY OF BIRKENHEAD JULIET CARROLL A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Liverpool John Moores University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy APRIL 2017 1 Renaissance to Regent Street: Harold Rathbone and the Della Robbia Pottery of Birkenhead Abstract This thesis examines the ways in which the unique creativity brought to late Victorian applied art by the Della Robbia Pottery was a consequence of Harold Rathbone’s extended engagement with quattrocento ceramics. This was not only with the sculpture collections in the South Kensington Museum but through his experiences as he travelled in Italy. In the first sustained examination of the development of the Della Robbia Pottery within the wider histories of the Arts and Crafts Movement, the thesis makes an original contribution in three ways. Using new sources of primary documentation, I discuss the artistic response to Italianate style by Harold Rathbone and his mentors Ford Madox Brown and William Holman Hunt, and consider how this influenced the development of the Pottery. Rathbone’s own engagement with Italy not only led to his response to the work of the quattrocento sculptor Luca della Robbia but also to the archaic sgraffito styles of Lombardia in Northern Italy; I propose that Rathbone found a new source of inspiration for the sgraffito workshop at the Pottery. The thesis then identifies how the Della Robbia Pottery established a commercial presence in Regent Street and beyond, demonstrating how it became, for a short time, an outstanding expression of these Italianate styles within the British Arts and Crafts Movement. -

Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer

Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer Manchester Art Gallery Reviewed by Dr Charlotte Starkey September 2011 It is always an illuminating experience to have the opportunity to see in one collection the major output of a significant artist, and the exhibition showing the work of Ford Madox Brown (1821 – 1893) at Manchester Art Gallery provides such an encounter. It is a reminder of the important links that cities such as Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham have with Pre-Raphaelite art in their permanent collections; and it is a fortunate legacy of Victorian entrepreneurs, that they helped to fund the museums, art galleries and other cultural institutions of the industrial cities and towns, seeking out the works of the Pre-Raphaelites in particular so enthusiastically. Ford Madox Brown was born in Calais in 1821. He was educated in Belgium, then lived in Paris and settled in London. Manchester became his home later in life when he was commissioned by Manchester Corporation to paint murals of the history of Manchester for Waterhouse’s Town Hall. He lived first in Crumpsall and then in the Victoria Park area of Manchester between 1881 and 1887. Brown’s life is chequered. He was one of the most gifted of Victorian artists, with a strict training in Europe as an artist. He did not join the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. He taught Dante Gabriel Rossetti. He was known by a wide circle of prominent Victorians either personally or through his art. In his personal life, however, he knew great loss and suffering: his first wife, Elisabeth, died in 1846 just five years after their marriage. -

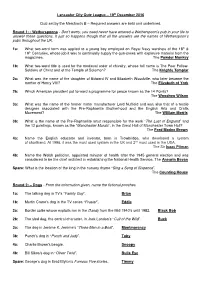

19Th December 2016 Quiz Set by the Merchants B – Required Answers

Lancaster City Quiz League – 19 th December 2016 Quiz set by the Merchants B – Required answers are bold and underlined. Round 1: - Wetherspoons - Don’t worry, you need never have entered a Wetherspoon’s pub in your life to answer these questions. It just so happens though that all the answers are the names of Wetherspoon’s pubs throughout the UK. 1a: What two-word term was applied to a young boy employed on Royal Navy warships of the 18 th & 19 th Centuries, whose job it was to continually supply the gun-crews with explosive material from the magazines. The Powder Monkey 1b: What two-word title is used for the medieval order of chivalry, whose full name is The Poor Fellow- Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon? The Knights Templar 2a: What was the name of the daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, who later became the mother of Henry VIII? The Elizabeth of York 2b: Which American president put forward a programme for peace known as the 14 Points? The Woodrow Wilson 3a: What was the name of the former motor manufacturer Lord Nuffield and was also that of a textile designer associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the English Arts and Crafts Movement? The William Morris 3b: What is the name of the Pre-Raphaelite artist responsible for the work “ The Last of England ” and the 12 paintings, known as the “ Manchester Murals ”, in the Great Hall of Manchester Town Hall? The Ford Madox Brown 4a: Name the English educator and inventor, born in Trowbridge, who developed a system of shorthand. -

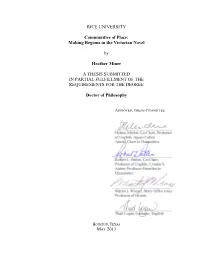

Making Regions in the Victorian Novel by Heather Miner a THESIS

RICE UNIVERSITY Communities of Place: Making Regions in the Victorian Novel by Heather Miner A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED , THESIS COMMITTEE : HOUSTON , TEXAS MAY 2013 Copyright Heather Miner 2013 ABSTRACT Communities of Place: Making Regions in the Victorian Novel Heather Miner Mid-way through George Eliot’s Middlemarch , the heroine of the novel develops a plan to move from her country estate in England’s Midlands to the northern industrial county of Yorkshire, where she intends to found a model factory town. Dorothea Brooke’s utopian fantasy of class relations, ultimately abandoned, hints at the broader regional and geospatial discourse at work in this canonical Victorian novel, but is equally ignored by critics and by other characters in Eliot’s realist masterpiece. In Communities of Place , I explore a new current of scholarship in Victorian studies by examining the role that England’s historic and geographic regions played in the development of the novel. Scholars of British literature and history have long argued that Victorian national and cultural identity was largely forged and promulgated from England’s urban centers. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the center became synonymous with London and, in the national metropolitan imagination, counties outside of London seemingly became homogenized into peripheral, anti-modern spaces. The critical tradition reinforces this historical narrative by arguing that the rise of nationalism precludes the development of regionalism. Thus, theorists of British nationalism have glossed over England’s intranational identity and have directed attention beyond England’s borders, toward France or Scotland, to analyze national identity within Great Britain as a whole. -

The Monuments and Memorials in Parliament Square, London

On Stage at the Theatre of State: The Monuments and Memorials in Parliament Square, London STUART JAMES BURCH A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of The Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2003 Abstract This thesis concerns Parliament Square in the City of Westminster, London. It is situated to the west of the Houses of Parliament (or New Palace at Westminster) and to the north of St. Margaret’s Church and Westminster Abbey. This urban space was first cleared at the start of the nineteenth-century and became a “square” in the 1860s according to designs by Edward Middleton Barry (1830-80). It was replanned by George Grey Wornum (1888-1957) in association with the Festival of Britain (1951). In 1998 Norman Foster and Partners drew up an (as yet) unrealised scheme to pedestrianise the south side closest to the Abbey. From the outset it was intended to erect statues of statesmen (sic) in this locale. The text examines processes of commissioning, execution, inauguration and reaction to memorials in this vicinity. These include: George Canning (Richard Westmacott, 1832), Richard I (Carlo Marochetti, 1851-66), Sir Robert Peel (Marochetti, 1853-67; Matthew Noble, 1876), Thomas Fowell Buxton (Samuel Sanders Teulon, 1865), fourteenth Earl of Derby (Matthew Noble, 1874), third Viscount Palmerston (Thomas Woolner, 1876), Benjamin Disraeli (Mario Raggi, 1883), Oliver Cromwell (William Hamo Thornycroft, 1899), Abraham Lincoln (Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1887/1920), Emmeline Pankhurst (Arthur George Walker, 1930), Jan Christian Smuts (Jacob Epstein, 1956) and Winston Churchill (Ivor Roberts-Jones, 1973) as well as possible future commemorations to David Lloyd George and Margaret Thatcher. -

Introduction To'ford Madox Brown and the Victorian Imagination'

LJMU Research Online Sheldon, JL and Trodd, C Introduction to 'Ford Madox Brown and the Victorian Imagination’ http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/186/ Article Citation (please note it is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from this work) Sheldon, JL and Trodd, C (2014) Introduction to 'Ford Madox Brown and the Victorian Imagination’. Visual Culture in Britain, 15 (3). pp. 227-238. ISSN 1471-4787 LJMU has developed LJMU Research Online for users to access the research output of the University more effectively. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LJMU Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of the record. Please see the repository URL above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information please contact [email protected] http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/ Authors: Colin Trodd and Julie Sheldon Email: [email protected] [email protected] Affiliation: University of Manchester Liverpool John Moores University Article Title: Introduction: Ford Madox Brown and the Victorian Imagination Abstract: The introduction to this special issue offers a critical overview of some of the most valuable historical engagements with Brown’s art. -

Ford Madox Brown: Works on Paper and Archive Material at Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery

FORD MADOX BROWN: WORKS ON PAPER AND ARCHIVE MATERIAL AT BIRMINGHAM MUSEUMS AND ART GALLERY VOLUME ONE: TEXT by LAURA MacCULLOCH A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham September 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This collaborative thesis focuses on the extensive collection of works on paper and related objects by Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893) held at Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery (BMAG). It is the first academic study to use Brown's works on paper as the basis for discussion. In doing so it seeks to throw light on neglected areas of his work and to highlight the potential of prints and drawings as subjects for scholarly research. The thesis comprises a complete catalogue of the works on paper by Brown held at BMAG and three discursive chapters exploring the strengths of the collection. Chapter one focuses on the significant number of literary and religious works Brown made in Paris between 1841 and 1844 and examines his position in the cross-cultural dialogues taking place in Europe in the mid-nineteenth century. -

Print This Article

Reattributing the Magdalene: Sandys to Shields at the NGV Alisa Bunbury Fig. 1. Frederic Shields. Sorrow. 1873. Coloured chalk over charcoal and wash on green paper, 58.3 × 53.0 cm. (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne). In 1904 the Director of the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), Bernard Hall (1859-1935), returned from a European buying trip, during which he spent the first instalment of the Gallery’s magnificent Felton Bequest. In his report, Hall wrote: From Mr. Trench, I bought a very moderate [sic] priced drawing by F. Sandys (£25) which is engraved amongst others in the Studio for October 1904 in an article on his work. It is old-fashioned in manner but Sandys has a certain standing amongst the big outsiders, and was accorded the posthumous honour of a special Exhibition of his works at The Burlington House this year at the same time as the Watts Exhibition was held.1 The work acquired by Hall was the large drawing Sorrow (Fig. 1). Created in coloured chalks on green paper, it depicts a life-size bust of a woman in robes and a veil, bending her head 1 B. Hall: Report to the Chairman of the Gallery Committee, July 1905, Felton Bequest Committee files, National Gallery of Victoria, p. 2. 118 Pre-Raphaelitism in Australasia Special Issue AJVS 22.2 (2018) over clasped hands. The rocky structure behind her, the covered vessel almost hidden by her flowing auburn hair, and the three crosses against the angry sky to the upper right clearly identify her as the grieving Mary Magdalene. -

Six Letters from Ford Madox Brown Joseph H

The Kentucky Review Volume 6 | Number 1 Article 5 Winter 1986 Memorials of a Friendship: Six Letters from Ford Madox Brown Joseph H. Gardner University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Gardner, Joseph H. (1986) "Memorials of a Friendship: Six Letters from Ford Madox Brown," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 6 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol6/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Library Notes 1 .L.S., Memorials of a Friendship: ;onal Six Letters from Ford Madox Brown Joseph H. Gardner l869; (New Ironically, it rained all day in Manchester on 15 September 1857; :ago: ironically because that Tuesday was one of the few bright days in rY of Frederic Shields's otherwise gloomy life. He had been born in fistory Hartlepool, 14 March 1833, the son of a bookbinder father and a n, dressmaker mother who moved to the neighborhood of St. Clement Danes, London, shortly after his birth. There his mother hers, opened a small shop while his father attempted to improve the family fortunes by enlisting as a mercenary in aid of Queen uary Isabella against the Carlist revolutionaries. -

Environmental Pressures on Building Design and Manchester's John Rylands Library

Journal of Design Hutory Vol. 13 No. 3 © 2000 The Design History Society Environmental Pressures on Building Design and Manchester's John Rylands Library Catherine Bowler and Peter Brimblecombe The enormous growth of the Victorian city and its parallel pollution problems confronted architects with great problems. Environmental pressures included denial of light, overcrowding, awkward sites, noise, accessibility and visibility of buildings, and air pollution. Corrosive pollutants were especially damaging to the minutely detailed Gothic architecture popular in Victorian Britain. Dense smoke made cities dark, coated the windows and penetrated inside damaging their contents. Basil Champneys, in designing Manchester's John Rylands Library, responded to these problems in an imaginative way that reflected the best of late nineteenth-century solutions. His thoughtful design made the most of available light and the crowded site. He used durable materials and colours that could resist the polluted air, while adopting electric light and air filtration inside. Valuable books and manuscripts were protected with carefully designed cases. Although not everyone was happy with the building, it has remained as an example of a determined attempt to cope with a very aggressive urban environment. Champneys confronted the conflict between design and the urban environment to produce a durable but pleasing library that proved suitable for users and provided secure accommodation for its contents. Keywords: air pollution—architecture—environmental design—interior design—library— urbanism Introduction continued to form the focus for many historical analyses of society in Victorian England. The environmental damage generated by the Indus- The environmental impact on die built environ- trial Revolution in England from the late eighteenth ment was also profound.