Introduction To'ford Madox Brown and the Victorian Imagination'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 14 March 2017 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Hingley, Richard (2016) 'Constructing the nation and empire : Victorian and Edwardian images of the building of Roman fortications.', in Graeco-Roman antiquity and the idea of Nationalism in the 19th century : case studies. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 153-174. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110473490-008 Publisher's copyright statement: The nal publication is available at www.degruyter.com Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Constructing the nation and empire: Victorian and Edwardian images of Roman building Richard Hingley ([email protected]) Introduction This paper draws upon four contrasting images dating to the period between 1857 and 1911 that show the building of Roman fortifications in Britain: a painting by William Bell Scott (1857), a mural by Ford Madox Brown (1879-80), a book illustration by Henry Ford (1911) and an engraving by Richard Caton Woodville (1911). -

Downloaded From: Version: Published Version Publisher: Visit Manchester

Lindfield, Peter (2020) Building a Civic Gothic Palace for Britain’s Cotton Em- pire: the architecture of Manchester Town Hall. Visit Manchester. Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/626278/ Version: Published Version Publisher: Visit Manchester Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk Building a Civic Gothic Palace for Britain’s Cotton Empire: the architecture of Manchester Town Hall - Visit Manchester 01/08/2020, 16:50 Map Tickets Buy the Guide on Jul 29 2020 Building a Civic Gothic Palace for Britain’s Cotton Empire: the architecture of Manchester Town Hall In Haunt The twenty-third instalment as part of an ongoing series for Haunt Manchester by Dr Peter N. Lindfield FSA,FSA, exploring Greater Manchester’s Gothic architecture and hidden heritage. Peter’s previous Haunt Manchester articles include features on Ordsall Hall,, Albert’s Schloss and Albert Hall,, thethe MancunianMancunian GothicGothic SundaySunday SchoolSchool of St Matthew’s,, Arlington House inin Salford,Salford, MinshullMinshull StreetStreet CityCity PolicePolice andand SessionSession CourtsCourts and their furniture,, Moving Manchester's Shambles,, Manchester’s Modern Gothic in St Peter’s Square,, whatwhat was St John’s Church,, Manchester Cathedral,, The Great Hall at The University of Manchester,, St Chad’s inin Rochdale and more. From the city’s striking Gothic features to the more unusual aspects of buildings usually taken for granted and history hidden in plain sight, a variety of locations will be explored and visited over the course of 2020. His video series on Gothic Manchester can be viewed here.. InIn thisthis articlearticle hehe considersconsiders oneone ofof Manchester’sManchester’s landmarklandmark GothicGothic buildings,buildings, ManchesterManchester TownTown Hall,Hall, whichwhich isis currently undergoing restoration work (see(see below).below). -

3. Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

• Of course, their patrons, largely the middle-class themselves form different groups and each member of the PRB appealed to different types of buyers but together they created a stronger brand. In fact, they differed from a boy band as they created works that were bought independently. As well as their overall PRB brand each created an individual brand (sub-cognitive branding) that convinced the buyer they were making a wise investment. • Millais could be trusted as he was a born artist, an honest Englishman and made an ARA in 1853 and later RA (and President just before he died). • Hunt could be trusted as an investment as he was serious, had religious convictions and worked hard at everything he did. • Rossetti was a typical unreliable Romantic image of the artist so buying one of his paintings was a wise investment as you were buying the work of a ‘real artist’. 1 • The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) had only seven members but influenced many other artists. • Those most closely associated with the PRB were Ford Madox Brown (who was seven years older), Elizabeth Siddal (who died in 1862) and Walter Deverell (who died in 1854). • Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris were about five years younger. They met at Oxford and were influenced by Rossetti. I will discuss them more fully when I cover the Arts & Crafts Movement. • There were many other artists influenced by the PRB including, • John Brett, who was influenced by John Ruskin, • Arthur Hughes, a successful artist best known for April Love, • Henry Wallis, an artist who is best known for The Death of Chatterton (1856) and The Stonebreaker (1858), • William Dyce, who influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and whose Pegwell Bay is untypical but the most Pre-Raphaelite in style of his works. -

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood: Painting

Marek Zasempa THE PRE-RAPHAELITE BROTHERHOOD: PAINTING VERSUS POETRY SUPERVISOR: prof. dr hab. Wojciech Kalaga Completed in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. UNIVERSITY OF SILESIA KATOWICE 2008 Marek Zasempa BRACTWO PRERAFAELICKIE – MALARSTWO A POEZJA PROMOTOR: prof. dr hab. Wojciech Kalaga UNIWERSYTET ŚLĄSKI KATOWICE 2008 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER 1: THE PRE-RAPHAELITE BROTHERHOOD: ORIGINS, PHASES AND DOCTRINES ............................................................................................................. 7 I. THE GENESIS .............................................................................................................................. 7 II. CONTEMPORARY RECEPTION AND CRITICISM .............................................................. 10 III. INFLUENCES ............................................................................................................................ 11 IV. THE TECHNIQUE .................................................................................................................... 15 V. FEATURES OF PRE-RAPHAELITISM: DETAIL – SYMBOL – REALISM ......................... 16 VI. THEMES .................................................................................................................................... 20 A. MEDIEVALISM ........................................................................................................................................ -

Renaissance to Regent Street: Harold Rathbone and the Della Robbia Pottery of Birkenhead

RENAISSANCE TO REGENT STREET: HAROLD RATHBONE AND THE DELLA ROBBIA POTTERY OF BIRKENHEAD JULIET CARROLL A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Liverpool John Moores University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy APRIL 2017 1 Renaissance to Regent Street: Harold Rathbone and the Della Robbia Pottery of Birkenhead Abstract This thesis examines the ways in which the unique creativity brought to late Victorian applied art by the Della Robbia Pottery was a consequence of Harold Rathbone’s extended engagement with quattrocento ceramics. This was not only with the sculpture collections in the South Kensington Museum but through his experiences as he travelled in Italy. In the first sustained examination of the development of the Della Robbia Pottery within the wider histories of the Arts and Crafts Movement, the thesis makes an original contribution in three ways. Using new sources of primary documentation, I discuss the artistic response to Italianate style by Harold Rathbone and his mentors Ford Madox Brown and William Holman Hunt, and consider how this influenced the development of the Pottery. Rathbone’s own engagement with Italy not only led to his response to the work of the quattrocento sculptor Luca della Robbia but also to the archaic sgraffito styles of Lombardia in Northern Italy; I propose that Rathbone found a new source of inspiration for the sgraffito workshop at the Pottery. The thesis then identifies how the Della Robbia Pottery established a commercial presence in Regent Street and beyond, demonstrating how it became, for a short time, an outstanding expression of these Italianate styles within the British Arts and Crafts Movement. -

Grafton Galleries

THE GRAFTON GALLERIES Grafton Street, Bond Street, W. HONORARY DIRECTORS. T. D. CROFT, ESQ. ALFRED FARQUHAR, ESQ. MARQUESS OF GRANBY. CARL MEYER, ESQ. HON. JOHM SCOTT MONTAGU, M.P EARL OF WHARNCLIFFE. A. STUART-WORTLEY, ESQ. SECRETARY. HENRY BISHOP, ESQ. 8, GRAFTON STREET, LONDON, W. 16•7 • INTRODUCTORY NOTE. WORD or two of introduction to the present Exhibition A may not come amiss. That Madox Brown was a remark able figure in the Art world of the present reign is now, I think, an acknowledged fact. That he was also a great painter has been generally ceded, even by those who, until lately, were his most ardent decriers. But there remains a body of public and cognoscenti who either ignore, or are ignorant of, both the man and his work. It is in the hope of reaching that body that the present Exhibition is held. "One-man shows" may or may not be desirable things; but, whether or no, such a show of Madox Brown's work is singularly appropriate, for did he not, along with a host of other incongruous things, invent the "one-man show " ? In 1865, at 191, Piccadilly, he exhibited a selection of 100 of his own works, a selection ranging from his earliest studies to his last picture, " Work," which had cost him eleven years' labour. Before that time no artist had been bold enough to challenge a verdict on so large a portion of his labours, though single pictures had been exhibited by artists like Mr. Holman Hunt and the late R. B. Martineau. -

Ford Madox Brown: Works on Paper and Archive Material at Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery

FORD MADOX BROWN: WORKS ON PAPER AND ARCHIVE MATERIAL AT BIRMINGHAM MUSEUMS AND ART GALLERY VOLUME TWO: ILLUSTRATIONS by LAURA MacCULLOCH A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham September 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. VOLUME TWO: ILLUSTRATIONS CONTENTS List of Illustrations page 1 List of Catalogue Illustrations page 13 Illustrations page 25 Catalogue Illustrations page 119 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig. 1 The Seeds and Fruits of English Poetry, 1845-1853, oil on canvas, Ashmolean Museum Fig. 2 Chaucer at the Court of Edward III, 1845-1851, oil on canvas, The Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney Fig. 3 Wycliffe reading his Translation of the Bible to John of Gaunt in the Presence of Chaucer and Gower (unframed), 1848, oil on canvas, Cartwright Hall Art Gallery, Bradford Fig. 4 Work, 1852-1865, oil on canvas, Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery Fig. 5 Last of England, 1852-1855, oil on panel, Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery Fig. -

Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer

Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer Manchester Art Gallery Reviewed by Dr Charlotte Starkey September 2011 It is always an illuminating experience to have the opportunity to see in one collection the major output of a significant artist, and the exhibition showing the work of Ford Madox Brown (1821 – 1893) at Manchester Art Gallery provides such an encounter. It is a reminder of the important links that cities such as Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham have with Pre-Raphaelite art in their permanent collections; and it is a fortunate legacy of Victorian entrepreneurs, that they helped to fund the museums, art galleries and other cultural institutions of the industrial cities and towns, seeking out the works of the Pre-Raphaelites in particular so enthusiastically. Ford Madox Brown was born in Calais in 1821. He was educated in Belgium, then lived in Paris and settled in London. Manchester became his home later in life when he was commissioned by Manchester Corporation to paint murals of the history of Manchester for Waterhouse’s Town Hall. He lived first in Crumpsall and then in the Victoria Park area of Manchester between 1881 and 1887. Brown’s life is chequered. He was one of the most gifted of Victorian artists, with a strict training in Europe as an artist. He did not join the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. He taught Dante Gabriel Rossetti. He was known by a wide circle of prominent Victorians either personally or through his art. In his personal life, however, he knew great loss and suffering: his first wife, Elisabeth, died in 1846 just five years after their marriage. -

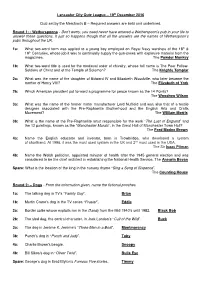

19Th December 2016 Quiz Set by the Merchants B – Required Answers

Lancaster City Quiz League – 19 th December 2016 Quiz set by the Merchants B – Required answers are bold and underlined. Round 1: - Wetherspoons - Don’t worry, you need never have entered a Wetherspoon’s pub in your life to answer these questions. It just so happens though that all the answers are the names of Wetherspoon’s pubs throughout the UK. 1a: What two-word term was applied to a young boy employed on Royal Navy warships of the 18 th & 19 th Centuries, whose job it was to continually supply the gun-crews with explosive material from the magazines. The Powder Monkey 1b: What two-word title is used for the medieval order of chivalry, whose full name is The Poor Fellow- Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon? The Knights Templar 2a: What was the name of the daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, who later became the mother of Henry VIII? The Elizabeth of York 2b: Which American president put forward a programme for peace known as the 14 Points? The Woodrow Wilson 3a: What was the name of the former motor manufacturer Lord Nuffield and was also that of a textile designer associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the English Arts and Crafts Movement? The William Morris 3b: What is the name of the Pre-Raphaelite artist responsible for the work “ The Last of England ” and the 12 paintings, known as the “ Manchester Murals ”, in the Great Hall of Manchester Town Hall? The Ford Madox Brown 4a: Name the English educator and inventor, born in Trowbridge, who developed a system of shorthand. -

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood: Painting Versus Poetry

Title: The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood: painting versus poetry Author: Marek Zasempa Citation style: Zasempa Marek. (2008). The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood: painting versus poetry. Praca doktorska. Katowice : Uniwersytet Śląski Marek Zasempa THE PRE-RAPHAELITE BROTHERHOOD: PAINTING VERSUS POETRY SUPERVISOR: prof. dr hab. Wojciech Kalaga Completed in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. UNIVERSITY OF SILESIA KATOWICE 2008 Marek Zasempa BRACTWO PRERAFAELICKIE – MALARSTWO A POEZJA PROMOTOR: prof. dr hab. Wojciech Kalaga UNIWERSYTET ŚLĄSKI KATOWICE 2008 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER 1: THE PRE-RAPHAELITE BROTHERHOOD: ORIGINS, PHASES AND DOCTRINES ............................................................................................................. 7 I. THE GENESIS .............................................................................................................................. 7 II. CONTEMPORARY RECEPTION AND CRITICISM .............................................................. 10 III. INFLUENCES ............................................................................................................................ 11 IV. THE TECHNIQUE .................................................................................................................... 15 V. FEATURES OF PRE-RAPHAELITISM: DETAIL – SYMBOL – REALISM ......................... 16 VI. THEMES ................................................................................................................................... -

Ford Madox Brown Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer

Jana Wijnsouw exhibition review of Ford Madox Brown Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012) Citation: Jana Wijnsouw, exhibition review of “Ford Madox Brown Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012), http://www.19thc- artworldwide.org/autumn12/wijnsouw-reviews-ford-madox-brown. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Wijnsouw: Ford Madox Brown Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012) Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer Manchester City Art Gallery September 24 – January 29, 2012 Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent February 25 – June 3, 2012 Catalogue: Julian Treuherz, with introductions by Robert Hoozee and Maria Balshaw, Ford Madox Brown. Brussels: Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent in association with Mercatorfonds, 2012. 160 pp., 115 color illustrations; chronology of the artist’s life; selected bibliography. € 24 ISBN: 978 90 6153 627 7 Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer offers a retrospective view of the oeuvre of this nineteenth-century British artist. Though Ford Madox Brown (1821–93) never actually joined the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, he was one of the main representatives of this British art movement. As the master of Dante Gabriël Rossetti (1828–82) and friend to many of the Pre- Raphaelite followers, he was closely affiliated with the group and both introduced and adopted some of the main principles of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. This exhibition aims to prove that Brown can even be considered as a Pre-Raphaelite pioneer, since he already developed a Pre-Raphaelite style before the Brotherhood was founded. -

Making Regions in the Victorian Novel by Heather Miner a THESIS

RICE UNIVERSITY Communities of Place: Making Regions in the Victorian Novel by Heather Miner A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED , THESIS COMMITTEE : HOUSTON , TEXAS MAY 2013 Copyright Heather Miner 2013 ABSTRACT Communities of Place: Making Regions in the Victorian Novel Heather Miner Mid-way through George Eliot’s Middlemarch , the heroine of the novel develops a plan to move from her country estate in England’s Midlands to the northern industrial county of Yorkshire, where she intends to found a model factory town. Dorothea Brooke’s utopian fantasy of class relations, ultimately abandoned, hints at the broader regional and geospatial discourse at work in this canonical Victorian novel, but is equally ignored by critics and by other characters in Eliot’s realist masterpiece. In Communities of Place , I explore a new current of scholarship in Victorian studies by examining the role that England’s historic and geographic regions played in the development of the novel. Scholars of British literature and history have long argued that Victorian national and cultural identity was largely forged and promulgated from England’s urban centers. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the center became synonymous with London and, in the national metropolitan imagination, counties outside of London seemingly became homogenized into peripheral, anti-modern spaces. The critical tradition reinforces this historical narrative by arguing that the rise of nationalism precludes the development of regionalism. Thus, theorists of British nationalism have glossed over England’s intranational identity and have directed attention beyond England’s borders, toward France or Scotland, to analyze national identity within Great Britain as a whole.