Environmental Pressures on Building Design and Manchester's John Rylands Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prospectus 2021/22

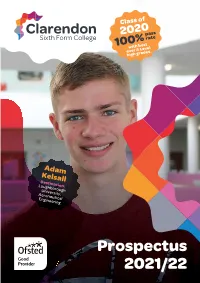

Lewis Kelsall 2020 Destination:e Cambridg 100 with bestLeve l University, ever A . Engineering high grades Adam Kelsall Destination: Loughborough University Aeronautical, Engineering Clarendon Sixth Form College Camp Street Ashton-under-Lyne OL6 6DF Prospectus 2021/22 03 Message from the Principal 04 Choose a ‘Good’ College 05 Results day success 06 What courses are on offer? 07 Choosing your level and entry requirements 08 How to apply 09 Study programme 12 Study skills and independent learning programme 13 Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) and Futures Programme 14 Student Hub 16 Dates for your diary 17 Travel and transport 18 University courses at Tameside College 19 A year in the life of... Course Areas 22 Creative Industries 32 Business 36 Computing 40 English and Languages 44 Humanities 50 Science, Mathematics and Engineering 58 Social Sciences 64 Performing Arts 71 Sports Studies and Public Services 02 Clarendon Sixth Form College Prospectus 2021/22 Welcome from the Principal Welcome to Clarendon Sixth Form College. As a top performing college in The academic and support Greater Manchester for school leavers, package to help students achieve while we aim very high for our students. Our studying is exceptional. It is personalised students have outstanding success to your needs and you will have access to a rates in Greater Manchester, with a range of first class support services at each 100% pass rate. stage of your learning journey. As a student, your career aspirations and This support package enables our students your college experience are very important to operate successfully in the future stages of to us. -

14-1676 Number One First Street

Getting to Number One First Street St Peter’s Square Metrolink Stop T Northbound trams towards Manchester city centre, T S E E K R IL T Ashton-under-Lyne, Bury, Oldham and Rochdale S M Y O R K E Southbound trams towardsL Altrincham, East Didsbury, by public transport T D L E I A E S ST R T J M R T Eccles, Wythenshawe and Manchester Airport O E S R H E L A N T L G D A A Connections may be required P L T E O N N A Y L E S L T for further information visit www.tfgm.com S N R T E BO S O W S T E P E L T R M Additional bus services to destinations Deansgate-Castle field Metrolink Stop T A E T M N I W UL E E R N S BER E E E RY C G N THE AVENUE ST N C R T REE St Mary's N T N T TO T E O S throughout Greater Manchester are A Q A R E E S T P Post RC A K C G W Piccadilly Plaza M S 188 The W C U L E A I S Eastbound trams towards Manchester city centre, G B R N E R RA C N PARKER ST P A Manchester S ZE Office Church N D O C T T NN N I E available from Piccadilly Gardens U E O A Y H P R Y E SE E N O S College R N D T S I T WH N R S C E Ashton-under-Lyne, Bury, Oldham and Rochdale Y P T EP S A STR P U K T T S PEAK EET R Portico Library S C ET E E O E S T ONLY I F Alighting A R T HARDMAN QU LINCOLN SQ N & Gallery A ST R E D EE S Mercure D R ID N C SB T D Y stop only A E E WestboundS trams SQUAREtowards Altrincham, East Didsbury, STR R M EN Premier T EET E Oxford S Road Station E Hotel N T A R I L T E R HARD T E H O T L A MAN S E S T T NationalS ExpressT and otherA coach servicesO AT S Inn A T TRE WD ALBERT R B L G ET R S S H E T E L T Worsley – Eccles – -

Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey Including Saint

Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret’s Church - UNESCO World Heritage Centre This is a cache of http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/426 as retrieved on Tuesday, April 09, 2019. UNESCO English Français Help preserve sites now! Login Join the 118,877 Members News & Events The List About World Heritage Activities Publications Partnerships Resources UNESCO » Culture » World Heritage Centre » The List » World Heritage List B z Search Advanced Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret’s Church Description Maps Documents Gallery Video Indicators Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret’s Church Westminster Palace, rebuilt from the year 1840 on the site of important medieval remains, is a fine example of neo-Gothic architecture. The site – which also comprises the small medieval Church of Saint Margaret, built in Perpendicular Gothic style, and Westminster Abbey, where all the sovereigns since the 11th century have been crowned – is of great historic and symbolic significance. Description is available under license CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 English French Arabic Chinese Russian Spanish Japanese Dutch Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret’s Church (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) © Tim Schnarr http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/426[04/09/2019 11:20:09 AM] Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret’s Church - UNESCO World Heritage Centre Outstanding Universal Value Brief synthesis The Palace of Westminster, Westminster Abbey and St Margaret’s Church lie next to the River Thames in the heart of London. With their intricate silhouettes, they have symbolised monarchy, religion and power since Edward the Confessor built his palace and church on Thorney Island in the 11th century AD. -

Road Closures & Reopenings

ROAD CLOSURES & REOPENINGS SUNDAY 19 MAY 2019 Dear Resident/Business Owner Mancunian Way Roundabout to Cornbrook; Chester Rd: from Hadfield St to Bridgewater Way;Chorlton Rd: from Jackson This year’s Simplyhealth Great Manchester Run will take place St to Mancunian Way; Chorlton St: from Portland St to Silver on Sunday 19th May 2019 and includes the Junior, Mini, 10k and St; City Rd East: from Albion St to Great Jackson St; Cross St: Half Marathon events. We’re celebrating 17 years of our hugely From Cross St to John Dalton St; Elevator Rd: from Wharfside popular running event this year. If you’re not taking part or can’t Way to Trafford Wharf Rd;Ellesmere St: from Hulme Hall Rd to get out to see the action live, the event will be broadcast live on Chester Rd; Fairfield St: from Ashton Old Rd to Mancunian Way; BBC 2 from 12:00 – 14:00 (please check TV listings for up to Great Bridgewater St: from Oxford St to Deansgate; Great date timings). Jackson St: from City Rd East to Chester Rd; Hardman St; Hulme Hall Rd: from Ellesmere St to Chester Rd; Jacksons Row; A stellar elite line-up will feature some of the world’s best athletes, Lloyd St; Major St: from Sackville St to Princess St; Manor St: at who will head a field of 30,000 competitors. The day starts with Mancunian Way; Midland St: from Hooper St to Ashton Old Rd; the Simplyhealth Great Manchester Run Half Marathon at 09:00, Minshul St: from Portland St to Aytoun St; Oxford St: from Peter followed by the Junior Run at 09:50 and the Mini Run at 10:50. -

Life in Stone Isaac Milner and the Physicist John Leslie

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT in Wreay, ensured that beyond her immediate locality only specialists would come to know and admire her work. RAYMOND WHITTAKER RAYMOND Panning outwards from this small, largely agricultural com- munity, Uglow uses Losh’s story to create The Pinecone: a vibrant panorama The Story of Sarah Losh, Forgotten of early nineteenth- Romantic Heroine century society that — Antiquarian, extends throughout Architect and the British Isles, across Visionary Europe and even to JENNY UGLOW the deadly passes of Faber/Farrer, Strauss and Giroux: Afghanistan. Uglow 2012/2013. is at ease in the intel- 344 pp./352 pp. lectual environment £20/$28 of the era, which she researched fully for her book The Lunar Men (Faber, 2002). Losh’s family of country landowners pro- vided wealth, stability and an education infused with principles of the Enlighten- ment. Her father, John, and several uncles were experimenters, industrialists, religious nonconformists, political reformers and enthusiastic supporters of scientific, literary, historical and artistic endeavour, like mem- bers of the Lunar Society in Birmingham, UK. John Losh was a knowledgeable collector of Cumbrian fossils and minerals. His family, meanwhile, eagerly consumed the works of geologists James Hutton, Charles Lyell and William Buckland, which revealed ancient worlds teeming with strange life forms. Sarah’s uncle James Losh — a friend of Pinecones, flowers and ammonites adorn the windows of Saint Mary’s church in Wreay, UK. political philosopher William Godwin, husband of the pioneering feminist Mary ARCHITECTURE Wollstonecraft — took the education of his clever niece seriously. She read all the latest books, and met some of the foremost inno- vators of the day, such as the mathematician Life in stone Isaac Milner and the physicist John Leslie. -

Gothic Beyond Architecture: Manchester’S Collegiate Church

Gothic beyond Architecture: Manchester’s Collegiate Church My previous posts for Visit Manchester have concentrated exclusively upon buildings. In the medieval period—the time when the Gothic style developed in buildings such as the basilica of Saint-Denis on the outskirts of Paris, Île-de-France (Figs 1–2), under the direction of Abbot Suger (1081–1151)—the style was known as either simply ‘new’, or opus francigenum (literally translates as ‘French work’). The style became known as Gothic in the sixteenth century because certain high-profile figures in the Italian Renaissance railed against the architecture and connected what they perceived to be its crude forms with the Goths that sacked Rome and ‘destroyed’ Classical architecture. During the nineteenth century, critics applied Gothic to more than architecture; they located all types of art under the Gothic label. This broad application of the term wasn’t especially helpful and it is no-longer used. Gothic design, nevertheless, was applied to more than architecture in the medieval period. Applied arts, such as furniture and metalwork, were influenced by, and followed and incorporated the decorative and ornament aspects of Gothic architecture. This post assesses the range of influences that Gothic had upon furniture, in particular by exploring Manchester Cathedral’s woodwork, some of which are the most important examples of surviving medieval woodwork in the North of England. Manchester Cathedral, formerly the Collegiate Church of the City (Fig.3), see here, was ascribed Cathedral status in 1847, and it is grade I listed (Historic England listing number 1218041, see here). It is medieval in foundation, with parts dating to between c.1422 and 1520, however it was restored and rebuilt numerous times in the nineteenth century, and it was notably hit by a shell during WWII; the shell failed to explode. -

The Industrial Revolution: 18-19Th C

The Industrial Revolution: 18-19th c. Displaced from their farms by technological developments, the industrial laborers - many of them women and children – suffered miserable living and working conditions. Romanticism: late 18th c. - mid. 19th c. During the Industrial Revolution an intellectual and artistic hostility towards the new industrialization developed. This was known as the Romantic movement. The movement stressed the importance of nature in art and language, in contrast to machines and factories. • Interest in folk culture, national and ethnic cultural origins, and the medieval era; and a predilection for the exotic, the remote and the mysterious. CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH Abbey in the Oak Forest, 1810. The English Landscape Garden Henry Flitcroft and Henry Hoare. The Park at Stourhead. 1743-1765. Wiltshire, England William Kent. Chiswick House Garden. 1724-9 The architectural set- pieces, each in a Picturesque location, include a Temple of Apollo, a Temple of Flora, a Pantheon, and a Palladian bridge. André Le Nôtre. The gardens of Versailles. 1661-1785 Henry Flitcroft and Henry Hoare. The Park at Stourhead. 1743-1765. Wiltshire, England CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH, Abbey in the Oak Forest, 1810. Gothic Revival Architectural movement most commonly associated with Romanticism. It drew its inspiration from medieval architecture and competed with the Neoclassical revival TURNER, The Chancel and Crossing of Tintern Abbey. 1794. Horace Walpole by Joshua Reynolds, 1756 Horace Walpole (1717-97), English politician, writer, architectural innovator and collector. In 1747 he bought a small villa that he transformed into a pseudo-Gothic showplace called Strawberry Hill; it was the inspiration for the Gothic Revival in English domestic architecture. -

Lancashire Historic Town Survey Programme

LANCASHIRE HISTORIC TOWN SURVEY PROGRAMME BURNLEY HISTORIC TOWN ASSESSMENT REPORT MAY 2005 Lancashire County Council and Egerton Lea Consultancy with the support of English Heritage and Burnley Borough Council Lancashire Historic Town Survey Burnley The Lancashire Historic Town Survey Programme was carried out between 2000 and 2006 by Lancashire County Council and Egerton Lea Consultancy with the support of English Heritage. This document has been prepared by Lesley Mitchell and Suzanne Hartley of the Lancashire County Archaeology Service, and is based on an original report written by Richard Newman and Caron Newman, who undertook the documentary research and field study. The illustrations were prepared and processed by Caron Newman, Lesley Mitchell, Suzanne Hartley, Nik Bruce and Peter Iles. Copyright © Lancashire County Council 2005 Contact: Lancashire County Archaeology Service Environment Directorate Lancashire County Council Guild House Cross Street Preston PR1 8RD Mapping in this volume is based upon the Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Lancashire County Council Licence No. 100023320 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Lancashire County Council would like to acknowledge the advice and assistance provided by Graham Fairclough, Jennie Stopford, Andrew Davison, Roger Thomas, Judith Nelson and Darren Ratcliffe at English Heritage, Paul Mason, John Trippier, and all the staff at Lancashire County Council, in particular Nik Bruce, Jenny Hayward, Jo Clark, Peter Iles, Peter McCrone and Lynda Sutton. Egerton Lea Consultancy Ltd wishes to thank the staff of the Lancashire Record Office, particularly Sue Goodwin, for all their assistance during the course of this study. -

A Building Stone Atlas of Greater Manchester

Strategic Stone Study A Building Stone Atlas of Greater Manchester First published by English Heritage June 2011 Rebranded by Historic England December 2017 Introduction The building stones of Greater Manchester fall into three Manchester itself, and the ring of industrial towns which well-defined groups, both stratigraphically and geographically. surround it, grew rapidly during the 18C and 19C, consuming The oldest building stones in Greater Manchester are derived prodigious quantities of local stone for buildings, pavements from the upper section of the Carboniferous Namurian and roads. As a result, the area contains a fairly sharp Millstone Grit Group. These rocks are exposed within the distinction between a built environment of Carboniferous denuded core of the Rossendale Anticline; the northern part of sandstone within the Pennine foothills to the north and east; the area, and also within the core of the main Pennine and urban areas almost wholly brick-built to the south and Anticline; the east part of the area. Within this group, the strata west. Because of rapacious demand during the mid to late 19C, tend to be gently inclined or horizontally bedded, and the resulting in rapid exhaustion of local stone sources, and sharp relief, coupled with lack of drift overburden, lent itself to perhaps allied to architectural whim, stone began to be large scale exploitation of the sandstones, especially in areas brought in by the railway and canal networks from more adjacent to turnpike roads. distant sources, such as Cumbria, Yorkshire, Derbyshire, and Staffordshire. During the late 20C and early 21C, a considerable Exposed on the flanks of the Rossendale and Pennine amount of new stone construction, or conservation repair, has anticlines, and therefore younger in age, are the rocks of the occurred, but a lack of active quarries has resulted in the Pennine Coal Measures Group. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 14 March 2017 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Hingley, Richard (2016) 'Constructing the nation and empire : Victorian and Edwardian images of the building of Roman fortications.', in Graeco-Roman antiquity and the idea of Nationalism in the 19th century : case studies. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 153-174. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110473490-008 Publisher's copyright statement: The nal publication is available at www.degruyter.com Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Constructing the nation and empire: Victorian and Edwardian images of Roman building Richard Hingley ([email protected]) Introduction This paper draws upon four contrasting images dating to the period between 1857 and 1911 that show the building of Roman fortifications in Britain: a painting by William Bell Scott (1857), a mural by Ford Madox Brown (1879-80), a book illustration by Henry Ford (1911) and an engraving by Richard Caton Woodville (1911). -

THE JOURNAL of ROMAN STUDIES All Rights Reserved

THE JOURNAL OF ROMAN STUDIES All rights reserved. THE JOURNAL OF ROMAN STUDIES VOLUME XI PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY FOR THE PRO- MOTION OF ROMAN STUDIES AT THE OFFICE OF THE SOCIETY, 19 BLOOMSBURY SQUARE, W.C.I. LONDON 1921 The printing of this -part was completed on October 20th, 1923. CONTENTS PAGE G. MACDONALD. The Building of the Antonine Wall : a Fresh Study of the Inscriptions I ENA MAKIN. The Triumphal Route, with particular reference to the Flavian Triumph 25 R. G. COLLINGWOOD. Hadrian's Wall: a History of the Problem ... ... 37 R. E. M. WHEELER. A Roman Fortified House near Cardiff 67 W. S. FERGUSON. The Lex Calpurnia of 149 B.C 86 PAUL COURTEAULT. An Inscription recently found at Bordeaux iof GRACE H. MACURDY. The word ' Sorex' in C.I.L. i2, 1988,1989 108 T. ASHBY and R. A. L. FELL. The Via Flaminia 125 J. S. REID. Tacitus as a Historian 191 M. V. TAYLOR and R G. COLLINCWOOD. Roman Britain in 1921 and 1922 200 J. WHATMOUGH. Inscribed Fragments of Stagshorn from North Italy ... 245 H. MATTINGLY. The Mints of the Empire: Vespasian to Diocletian ... 254 M. L. W. LAISTNER. The Obelisks of Augustus at Rome ... 265 M. L. W. LAISTNER. Dediticii: the Source of Isidore (Etym. 9, 4, 49-50) 267 Notices of Recent Publications (for list see next page) m-123, 269-285 M. CARY. Note on ' Sanguineae Virgae ' (J.R.S. vo. ix, p. 119) 285 Errata 287 Proceedings of the Society, 1921 288 Report of the Council and Statement of Accounts for the year 1920 289 Index .. -

Planning and Highways Committee on 27 July 2017 Item 12. 3 St Peter's

Manchester City Council Item No. 12 Planning and Highways Committee 27 July 2017 Application Number Date of Appln Committee Date Ward 116189/FO/2017 8th May 2017 27th Jul 2017 City Centre Ward Proposal Demolition of an existing building and construction of a 20 storey building (and basement) comprising a 328 bedroom hotel (Use Class C1) (with ancillary food and drink uses) on ground floor to 8th floor and a 262 bedroom apart-hotel (Class C1) with ancillary reception area, food and drink uses and staff facilities on floors 9-20. Location 3 St Peters Square (formally Peterloo House), Manchester, M1 4LF Applicant Mr Andrew Lavin , Property Alliance Group, C/o Agent Agent Mr Neil Lucas, HOW Planning, 40 Peter Street, Manchester, M2 5GP, Description The Site The site is 0.12 hectares in size and located in Manchester city centre. It is bounded by George Street, Dickinson Street, St Peter’s Square and Back George Street. Located in the George Street Conservation Area and next to the St Peter’s Square Conservation Area, the site forms part of the Civic Quarter Regeneration Framework area, a major regeneration priority for the City Council. There are no listed buildings on the site, but there are several nearby including the Grade II listed Princess Buildings (which includes 72-76 George Street next to the site boundary), Manchester Town Hall and Town Hall Extension (Grade I and II* respectively), Manchester Central Library (Grade II*) and the City Art Gallery and Athenaeum (Grade I and II*). The site is currently home to a seven storey office building called Peterloo House and private car park.