The Great Rift

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Knowledge and Practice of Testicular Self-Examination Among Secondary Students at Ntare School in Mbarara District, South Western Uganda

Open Access Research Knowledge and practice of testicular self-examination among secondary students at Ntare School in Mbarara District, South western Uganda Catherine Atuhaire1, Ambrose Byamukama1, Rosaline Yumumkah Cumber2, Samuel Nambile Cumber3,4,5,& 1Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Nursing, Mbarara, Uganda, 2Faculty of Political Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa, 3Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa, 4Section for Epidemiology and Social Medicine, Department of Public Health, Institute of Medicine (EPSO), The Sahlgrenska Academy at University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 5School of Health Systems and Public Health Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria Private Bag X323, Gezina, Pretoria, South Africa &Corresponding author: Samuel Nambile Cumber, School of Health Systems and Public Health Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria Private Bag X323, Gezina, Pretoria, South Africa Key words: Knowledge, practice, testicular, self-examination, Uganda Received: 12/02/2018 - Accepted: 15/03/2019 - Published: 06/06/2019 Abstract Introduction: testicular self-examination (TSE) is a screening technique that involves inspection of the appearance and palpation of the testes to detect any changes from the normal. Globally, the incidence of cancer has increased among which is testicular cancer (TC). Data on this topic among male secondary school adolescents in Uganda is limited therefore this study sought to assess the knowledge and practice of testicular self-examination among secondary students at Ntare School, Mbarara District in south western Uganda. The objective of the study is to assess the knowledge and practice of testicular self-examination among secondary students at Ntare School in Mbarara district, south western Uganda. -

Vote: 761 2014/15 Quarter 3

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 761 Mbarara Municipal Council 2014/15 Quarter 3 Structure of Quarterly Performance Report Summary Quarterly Department Workplan Performance Cumulative Department Workplan Performance Location of Transfers to Lower Local Services and Capital Investments Submission checklist I hereby submit _________________________________________________________________________. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:761 Mbarara Municipal Council for FY 2014/15. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Town Clerk, Mbarara Municipal Council Date: 5/8/2015 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District)/ The Mayor (Municipality) Page 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report Vote: 761 Mbarara Municipal Council 2014/15 Quarter 3 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Cumulative Receipts Performance Approved Budget Cumulative % Receipts Budget UShs 000's Received 1. Locally Raised Revenues 3,578,143 2,593,379 72% 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 1,510,962 1,124,046 74% 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 16,722,918 5,649,243 34% 2c. Other Government Transfers 4,366,138 3,838,831 88% 3. Local Development Grant 227,031 193,522 85% 4. Donor Funding 198,376 199,070 100% Total Revenues 26,603,568 13,598,090 51% Overall Expenditure Performance Cumulative Releases and Expenditure Perfromance -

Makerere University Business School

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY BUSINESS SCHOOL ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT PRIVATE ADMISSIONS, 2018/2019 ACADEMIC YEAR PRIVATE THE FOLLOWING HAVE BEEN ADMITTED TO THE FOLLOWING PROGRAMME ON PRIVATE SCHEME BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ACCOUNTING (MUBS) COURSE CODE ACC INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0801/525 NAMIRIMU Carolyne Mirembe 2017 F U 55 NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 45.8 2 U0083/542 ANKUNDA Crissy 2017 F U 46 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.7 3 U0956/649 SSALI PAUL 2017 M U 49 NAMIREMBE HILLSIDE S.S. 45.4 4 U0169/626 MUHANUZI Robert 2017 M U 102 ST.ANDREA KAHWA'S COL., HOIMA 45.2 5 U0048/780 NGANDA Nasifu 2017 M U 88 MASAKA SECONDARY SCHOOL 44.5 6 U0178/502 ASHABA Lynn 2017 F U 12 CALTEC ACADEMY, MAKERERE 43.6 7 U0060/583 ATUGONZA Sharon Mwesige 2017 F U 13 TRINITY COLLEGE, NABBINGO 43.6 8 U0763/546 NYALUM Connie 2017 F U 43 BUDDO SEC. SCHOOL 43.3 9 U2546/561 PAKEE PATIENCE 2016 F U 55 PRIDE COLLEGE SCHOOL MPIGI 43.3 10 U0334/612 KYOMUGISHA Rita Mary 2011 F U 55 UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 43.1 11 U0249/532 MUGANGA Diego 2017 M U 55 ST.MARIA GORETTI S.S, KATENDE 42.1 12 U1611/629 AHUURA Baseka Patricia 2017 F U 34 OURLADY OF AFRICA SS NAMILYANGO 41.5 13 U0923/523 NABUUMA MAJOREEN 2017 F U 55 ST KIZITO HIGH SCH., NAMUGONGO 41.5 14 U2823/504 NASSIMBWA Catherine 2017 F U 55 ST. HENRY'S COLLEGE MBALWA 41.3 15 U1609/511 LUBANGAKENE Innocent 2017 M U 27 NAALYA SSS 41.3 16 U0417/569 LUBAYA Racheal 2017 F U 16 LUZIRA S.S.S. -

George Mugarukye.Pdf

CONFLICT MANAGEMENT APPROACHES AND STRIKING IN SELECTED SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN MBARARA MUNICIPALITY BY GEORGE MUGARUKYE MAPAM/ 0001/131/DU BGC, DGC (KIU) /CERT PAM (MUK) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AW ARD OF MASTERS DEGREE IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION AND MANAGEMENT OF KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY NOVEMBER, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare to the best of my knowledge and ability that this is my original work and it has never been submitted to any University or any higher institution of learning for award of any qualification l \ - '1 ."\ ( Signed .... ......... Date . mV.t'.S ..-.. ....... .ct:<:-) . ...~. ....... GEORGE MUGARUKYE MAPAM/ 0001/131./DU APPROVAL This dissertation has been submitted for examination under our approval as the University supervisors Supervisor Signed .................. ..... ~~oLv)/4) Date ... ~ ........ .... ........ MR. LAWREN CE MBABAZI Supervisor 11 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my family, friends and relatives who helped me spiritually morally and financially in my education. I specifically dedicate it to my beloved daughter Ankunda Kerry Mugarukye. 111 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to my supervisors; Dr. Medard Twinamatsiko Katonera and Mr. Lawrence Mbabazi for their helpful supervision, comments and guidance about this research from the start to the end. Without their efforts and advice this research would not have been accomplished. Am also humbled to acknowledge the efforts of my family members paiticularly my wife, mum, sisters and brothers of whom if they were not there for me since I started my studies, probably I would not have taken an extra mile to reach where I have reached. -

Kyambogo University National Merit Admission 2019-2020

KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2019/2020 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE COURSE CODE AFD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U1223/539 BALABYE Alice Esther 2018 F U 16 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 47.9 2 U1223/589 NANYONJO Jovia 2018 F U 85 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 47.7 3 U0801/501 NAKIMBUGE Kevin 2018 F U 55 NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 45.9 4 U1688/510 TUMWESIGE Hilda Sylivia 2018 F U 34 KYADONDO SS 45.8 5 U1224/536 AKELLO Jovine 2018 F U 31 ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 45.8 6 U0083/693 TUKASHABA Catherine 2018 F U 50 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.7 7 U1609/503 OTHIENO Tophil 2018 M U 54 NAALYA SSS 45.7 8 U0046/508 ATUHAIRE Comfort 2018 F U 123 MARYHILL HIGH SCHOOL 45.6 9 U2236/598 NABULO Gorret 2018 F U 52 ST.MARY'S COLLEGE, LUGAZI 45.6 10 U0083/541 BEINOMUGISHA Izabera 2018 F U 50 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.5 KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2019/2020 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF VOCATIONAL STUDIES IN AGRICULTURE WITH EDUCATION COURSE CODE AGD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0059/548 SSEGUJJA Emmanuel 2018 M U 97 BUSOGA COLLEGE, MWIRI 33.2 2 U1343/504 AKOLEBIRUNGI Cecilia 2018 F U 30 AVE MARIA SECONDARY SCHOOL 31.7 3 U3297/619 KIYIMBA Nasser 2018 M U 51 BULOBA ROYAL COLLEGE 31.4 4 U1476/577 KIRYA Brian 2018 M U 93 RAINBOW HIGH SCHOOL, BUDAKA 31.2 5 U0077/619 KIZITO -

Bachelor of Arts with Education

BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH EDUCATION COURSE CODE EDA INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY SCHOOL 1 U1034/550 MUTEBI Wycliff 2010 M U BAPTIST HIGH SCHOOL, KITEBI 2 U2320/527 NAMUTEBI Annet 2010 F U KISOZI HIGH SCHOOL 3 U0026/626 LIBERTY Christopher 2010 M U KIGEZI COLLEGE, BUTOBERE 4 U0801/542 LUYIGA Maryanne 2010 F U NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 5 U0017/546 AOL Sharon 2010 F U IGANGA SECONDARY SCHOOL 6 U0512/555 SSEMWOGERERE Swaibu 2010 M U NAMAGABI S S 7 U0108/564 NANSUBUGA Christie 2010 F U KASAWO SECONDARY SCHOOL 8 U0959/501 KIZITO Pius 2010 M U NAMIRYANGO SS 9 U1354/661 NANUNGI Sherina 2009 F U MERRYLAND HIGH SCHOOL 10 U0183/625 WANYANA Breder 2010 F U UGANDA MARTYRS'HIGH SC. RUBAGA 11 U0052/521 BAHATI Preston 2010 M U MBARARA HIGH SCHOOL 12 U0956/736 NAKADAMA Wangubo Hadijah 2010 F U NAMIREMBE HILLSIDE S.S. 13 U0149/552 NAKANDI Sharifah 2010 F U KIBIBI SECONDARY SCHOOL 14 U1224/541 ATUHAIRE Phiona 2010 F U ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 15 U1664/503 KAZIBWE EMMANUEL 2009 M U ST. MARK'S SS NAMAGOMA 16 U0348/502 MUYIMBWA Geofrey 2010 M U ST.JOHN'S SEC.SCH., KABUWOKO 17 U2177/576 SSEMBIITO Sadamu 2010 M U MBOGO COLLEGE SCHOOL 18 U0956/777 ABAASA Phionah 2010 F U NAMIREMBE HILLSIDE S.S. 19 U0404/507 NAMBOOZE Winnie 2010 F U KIBUUKA MEMORIAL SCHOOL, MPIGI 20 U2061/660 NALUMAGA Eva 2010 F U MASAKA SECONDARY SCHOOL, ANNEX 21 U0298/670 NAKALEMA Rebecca 2010 F U LUWERO SECONDARY SCHOOL 22 U1350/501 NANTEGE Josephine Gladys 2010 F U MIDLAND HIGH SCHOOL 23 U1223/563 NAMATOVU Yudaya 2010 F U SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 24 U0660/529 NAKAWOOYA Rashidah 2010 F U KIJAGUZO SEC. -

Archives of the Bishop of Uganda

Yale University Library Yale Divinity School Library Archives of the Bishop of Uganda UCU-RG1 Christine Byaruhanga 2007 Revised: 2010-02-03 New Haven, Connecticut Copyright © 2007 by the Yale University Library. Archives of the Bishop of Uganda UCU-RG1 - Page 2 Table of Contents Overview 11 Administrative Information 11 Provenance 11 Information about Access 11 Ownership & Copyright 11 Cite As 11 Historical Note 12 Description of the Papers 12 Arrangement 13 Collection Contents 14 Series I. Administrative/Governing Bodies, 1911-1965 14 Church Missionary Society (CMS) 14 CMS Africa Secretary and General (London), 1955-1961 14 CMS East Africa Volume 1, 1953-1957 15 Dioceses 31 Uganda Diocese 31 Deanery Council Minutes 31 Diocesan Association of the Uganda Diocese 32 Diocesan Boards of the Uganda Diocese 34 Diocesan Council of the Uganda Diocese 35 Upper Nile Diocese 37 Diocesan Council of the Upper Nile Diocese (Book), 1955-1969 37 Diocesan Boards of Finance of the Upper Nile Diocese (Book), 1955-1962 37 Diocese of the Upper Nile 37 Ankole/Kigezi Diocese 39 Rural Deaneries 41 Deanery of Ankole 41 Ankole 41 Mbarara 41 Ecclesiastical Correspondences 42 Buganda 43 Deanery of Buddu 43 Deanery of Bukunja 44 Deanery of Bulemezi 45 Deanery of Busiro 46 Deanery of Bwekula 46 Deanery of Gomba 48 Deanery of Kako 49 Archives of the Bishop of Uganda UCU-RG1 - Page 3 Deanery of Kooki 49 Deanery of Kyagwe 49 Deanery of Mengo 50 Deanery of Ndeje 50 Deanery of Singo 51 Bunyoro 52 Deanery of Bunyoro 52 Busoga 54 Deanery of Busoga 54 Toro/Fort Portal 55 -

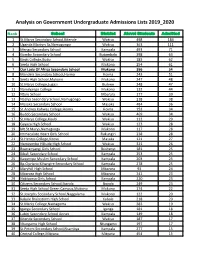

Analysis on Government Undergraduate Admissions Lists 2019 2020

Analysis on Government Undergraduate Admissions Lists 2019_2020 Rank School District Alevel Students Admitted 1 St.Marys Secondary School,Kitende Wakiso 498 184 2 Uganda Martyrs Ss,Namugongo Wakiso 363 111 3 Mengo Secondary School Kampala 493 71 4 Gombe Secondary School Butambala 398 63 5 Kings College,Budo Wakiso 183 62 6 Seeta High School Mukono 254 61 7 Our Lady Of Africa Secondary School Mukono 396 54 8 Mandela Secondary School,Hoima Hoima 243 51 9 Seeta High School,Mukono Mukono 247 48 10 St.Marys College,Lugazi Buikwe 248 47 11 Namilyango College Mukono 132 44 12 Ntare School Mbarara 177 39 13 Naalya Secondary School,Namugongo Wakiso 218 38 14 Masaka Secondary School Masaka 484 36 15 St.Andrea Kahwas College,Hoima Hoima 153 34 16 Buddo Secondary School Wakiso 469 34 17 St.Marys College,Kisubi Wakiso 112 29 18 Gayaza High School Wakiso 123 28 19 Mt.St.Marys,Namagunga Mukono 117 28 20 Immaculate Heart Girls School Rukungiri 238 28 21 St.Henrys College,Kitovu Masaka 121 27 22 Namirembe Hillside High School Wakiso 321 26 23 Bweranyangi Girls School Bushenyi 181 25 24 Kibuli Secondary School Kampala 253 25 25 Kawempe Muslim Secondary School Kampala 203 25 26 Bp.Cipriano Kihangire Secondary School Kampala 278 25 27 Maryhill High School Mbarara 93 24 28 Mbarara High School Mbarara 241 23 29 Nabisunsa Girls School Kampala 220 23 30 Citizens Secondary School,Ibanda Ibanda 249 23 31 Seeta High School Green Campus,Mukono Mukono 174 22 32 St.Josephs Secondary School,Naggalama Mukono 122 20 33 Kabale Brainstorm High School Kabale 218 20 34 St.Marks -

School Location; School Planning; *Secondexy Schools; Site Selection IDENTIFIERS School Eapping; *Uganda

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 190 EA 005 923 AUTHOR Gould, V. T. S. TITLE Planning the Location of Schools: Ankole District, Uganda. Case Studies -- 3. INSTITUTION United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organi:mtion, Paris (France). International Inst. for Educat%onal Planning. REPORT NO ISBN-9:!-803-1057-7 PUB DATE 73 NOTE 88p. AVAILABLE FROM Unipub1 Inc., P.O. Box 443, New York, New York 10016 (Order number ISBN 92-803-1057-7, $10.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.15 HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Case Studies; Educational Planning; *Elementary Schools; Foreign Countries; Geographic Location; Maps; Methodology; *Planning; *School Demography; School Mstricts; *School Location; School Planning; *Secondexy Schools; Site Selection IDENTIFIERS School Eapping; *Uganda ABSTRACT Ahkole District, Uganda, is typical of many developing areas of Africa, characterized by rapid population change (a result of both growth and redistribution), inadequate school provision, and severe financial constraints. The study relates the present patterns and organization of elementary and secondary level educational provision to the existing and projected population distribution. Population density is seen as a crucial variable affecting the choice of strategy for the development of the school map. Basic techniques of locational analysis are used to suggest a policy for expanding the elementary level system and to identify suitable locations for new secondary level schools. (Photographs may reproduce poorly.)(Author) Planning the location of schools: case studies-.3. An IIEP research project directed by'Jacques Hallak U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCE° EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY Planning the location of schools: Ankole District, Uganda "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL BY MICRO. -

Budget Monitoring Report Q1 FY2013-14.Pdf

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Budget Monitoring Report Quarter One Financial Year 2013/2014 February, 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS 5 FOREWORD 11 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 12 PART 1: INTRODUCTION 32 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND 33 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY 34 2.1 Process 34 2.2 Methodology 34 2.3 Limitations of the report 35 2.4 Structure of the report 35 PART 2: FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE 36 CHAPTER 3: FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE OF CENTRAL GOVERNMENT 37 3.1 Introduction 37 3.2 Scope and Methodology 37 3.3 Financial Performance of selected Ministries. 37 3.4 Conclusions 50 3.5 Recommendation 50 CHAPTER 4: FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS 51 4.1 Introduction 51 4.2 Objectives 51 4.3 Scope and Methodology 51 4.4 Limitations 51 4.5 Findings 51 PART 3: PHYSICAL PERFORMANCE 65 CHAPTER 5: AGRICULTURE 66 5.1 Introduction 66 5.2 Export Goat Breeding and Production 67 5.3 Increasing Mukene for Home Consumption 80 5.4 National Livestock Research Institute 95 5.5 Support to Fisheries Mechanization and Weed Control 109 5.6 Support to Implementation of Quality Assurance for Fish Marketing 125 CHAPTER 6: EDUCATION 140 6.1 Introduction 140 6.2 The ADB IV project 140 6.3 The Centres of Excellence 142 6.4 Existing Seed Secondary Schools expanded under ADB IV 157 6.5 New Seed Secondary Schools Constructed Under ADB IV 161 6.6 Existing Seed Secondary Schools for Expansion 167 6.7 New Seed Secondary Schools Constructed To 100% 171 3 6.8 Additional centres of excellence for rehabilitation and expansion 176 CHAPTER 7: ENERGY 182 7.1 Introduction 182 7.2 Scope -

Government Secondary Schools SN School District EMIS CODE

Government Secondary Schools SN School District EMIS CODE 1 ABIM S.S ABIM 4527 2 LOTUKE SEED S.S ABIM 188003 3 MORULEM GIRLS' S.S ABIM 188000 4 BIYAYA S.S.S ADJUMANI 11990 5 ALERE S.S.S ADJUMANI 418011 6 ADJUMANI S.S.S ADJUMANI 12016 7 DZAIPI S.S ADJUMANI 12034 8 OFUA S.S ADJUMANI 418002 9 ST MARY ASSUMPTA S.S.S ADJUMANI 12058 10 ADILANG SECONDARY SCHOOL AGAGO 4145 11 PATONGO S.S AGAGO 4153 12 ST CHARLES LWANGA AGAGO 4187 13 LIRA PALWO S.S AGAGO 4221 14 OMOT SECONDARY SCHOOL AGAGO 518015 15 AKWANG S.S AGAGO 518013 16 ST THERESA GIRLS SS ALEBTONG 4958 17 OMORO SS ALEBTONG 5019 18 AKII BUA COMP.SS ALEBTONG 208004 19 FATIMA ALOI COMP.GIRLS SS ALEBTONG 208026 20 ALOI SS ALEBTONG 4980 21 APALA SS ALEBTONG 5013 22 AGWINGIRI GIRL'S SCHOOL AMOLATAR 4908 23 AMOLATAR SS AMOLATAR 4911 24 ALEMERE COMPREHENSIVE SS AMOLATAR 208023 25 APUTI SS AMOLATAR 4888 26 AWELO SS AMOLATAR 4897 27 NAMASALE SEED SS AMOLATAR 690000 28 POKOT SS AMUDAT 268000 29 ST PAUL ABARILELA SS AMURIA 660000 30 AMURIA SS AMURIA 12423 31 MORUNGATUNY SSS AMURIA 660001 32 ORUNGO HIGH SCHOOL AMURIA 12432 33 ST PETERS SS AMURIA AMURIA 12456 34 JOHN ELURU MEM SS AMURIA 448017 35 ST FRANCIS ACUMET AMURIA 12473 36 LABIRA GIRLS SS AMURIA 12488 37 LWANI MEMORIAL COLLEGE AMURU 68006 38 KEYO SS AMURU 1432 39 ST MARY'S COLLEGE LACOR AMURU 1430 40 PABBO SS AMURU 1437 41 ADUKU S.S APAC 74 42 IKWERA GIRLS S.S APAC 82 43 CHAWENTE S.S APAC 92 44 INOMO S.S APAC 101 45 NAMBIASO AGRO S.S APAC 106 46 AKOKORO S.S APAC 121 47 APAC S.S APAC 148 48 CHEGERE S.S APAC 156 49 IBUJE S.S APAC 176 50 ADUMI SS -

Integra Ng Human Rights Educa on in Primary and Post

Integra� ng Human Rights Educa� on in Primary and Post – Primary Ins� tu� ons in Uganda A situa� on Analysis Report and Na� onal Implementa� on Strategy for Human Rights Educa� on December 2012 Integra� ng Human Rights Educa� on in Primary and Post – Primary Ins� tu� ons in Uganda A situa� on Analysis Report and Na� onal Implementa� on Strategy for Human Rights Educa� on December 2012 Table of Contents List of Acronyms..............................................................................................................iv Foreword.......................................................................................................................viii Acknowledgement..........................................................................................................ix Execu� ve Summary.........................................................................................................x Situa� on Analysis Report of the Current Status of Human Rights and Life Skills Educa� on in Primary and Post – Primary Educa� on Ins� u� ons in Uganda.........1 Introduc� on....................................................................................................................................................1 Background to Human Rights Educa� on........................................................................................................1 Introducing Human Rights Educa� on in Uganda within the framework of the WPHRE.................................2 Purpose of the situa� on analysis....................................................................................................................3