How Do Journalists Edit the Content of Press Releases for Publication in Online Newspapers?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Starbucks Corp. (SBUX) Annual General Meeting

Corrected Transcript 18-Mar-2020 Starbucks Corp. (SBUX) Annual General Meeting Total Pages: 14 1-877-FACTSET www.callstreet.com Copyright © 2001-2020 FactSet CallStreet, LLC Starbucks Corp. (SBUX) Corrected Transcript Annual General Meeting 18-Mar-2020 CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Kevin Johnson John Culver President, Chief Executive Officer & Director, Starbucks Corp. Group President-International, Channel Development and Global Coffee & Tea, Starbucks Corp. Rachel A. Gonzalez Executive Vice President, General Counsel & Secretary, Starbucks Corp. Rosalind Gates Brewer Chief Operating Officer, Group President & Director, Starbucks Corp. Justin Danhof General Counsel & Director-Free Enterprise Project, The National Patrick J. Grismer Center for Public Policy Research Executive Vice President & Chief Financial Officer, Starbucks Corp. Rossann Williams Executive Vice President & President-U.S. company-operated business and Canada, Starbucks Corp. ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION SECTION Kevin Johnson President, Chief Executive Officer & Director, Starbucks Corp. Well, good morning from Seattle, Washington, and welcome to Starbucks' 28th Annual Meeting of Shareholders. I'm so pleased to have you join this webcast and I want to open by thanking the Starbucks Board of Directors, all of whom are joining -

Thesis Old Media, New Media

THESIS OLD MEDIA, NEW MEDIA: IS THE NEWS RELEASE DEAD YET? HOW SOCIAL MEDIA ARE CHANGING THE WAY WILDFIRE INFORMATION IS BEING SHARED Submitted By Mary Ann Chambers Department of Journalism and Technical Communication In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring 2015 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Joseph Champ Peter Seel Tony Cheng Copyright by Mary Ann Chambers 2015 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT OLD MEDIA, NEW MEDIA: IS THE NEWS RELEASE DEAD YET? HOW SOCIAL MEDIA ARE CHANGING THE WAY WILDFIRE INFORMATION IS BEING SHARED This qualitative study examines the use of news releases and social media by public information officers (PIO) who work on wildfire responses, and journalists who cover wildfires. It also checks in with firefighters who may be (unknowingly or knowingly) contributing content to the media through their use of social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook. Though social media is extremely popular and used by all groups interviewed, some of its content is unverifiable ( Ma, Lee, & Goh, 2014). More conventional ways of doing business, such as the news release, are filling in the gaps created by the lack of trust on the internet and social media sites and could be why the news release is not dead yet. The roles training, friends, and colleagues play in the adaptation of social media as a source is explored. For the practitioner, there are updates explaining what social media tools are most helpful to each group. For the theoretician, there is news about changes in agenda building and agenda setting theories caused by the use of social media. -

Subsidizing the News? Organizational Press Releases' Influence on News Media's Agenda and Content Boumans, J

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Subsidizing the news? Organizational press releases' influence on news media's agenda and content Boumans, J. DOI 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1338154 Publication date 2018 Document Version Final published version Published in Journalism Studies License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Boumans, J. (2018). Subsidizing the news? Organizational press releases' influence on news media's agenda and content. Journalism Studies, 19(15), 2264-2282. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1338154 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 SUBSIDIZING THE NEWS? Organizational press releases’ influence on news media’s agenda and content Jelle Boumans The relation between organizational press releases and newspaper content has generated consider- able attention. -

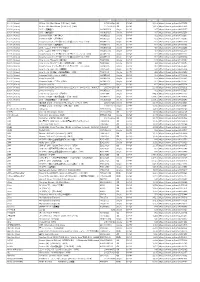

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

Washington Apple Pi Journal, May 1988

Wa1hington Journal of WasGhington Appl e Pi, Ltd Volume. 10 may 1988 number 5 Hiahliaht.1 ' . ~ The Great Apple Lawsuit- (pgs4&so) • Timeout AppleWorks Enhancements - I IGs •Personal Newsletter & Publish It! ~ MacNovice: Word Processing- The Next Generati on ~ Views & Reviews: MidiPaint and Performer ~ Macintosh Virus: Technical Notes In This Issue. Officers & Staff, Editorial ................................ ...................... 3 Personal Newsletter and Publish It! .................... Ray Settle 40* President's Corner ........................................... Tom Warrick 4 • GameSIG News ....................................... Charles Don Hall 41 Event Queue, General Information, Classifieds ..................... 6 Plan for Use of Tutorial Tapes & Disks ................................ 41 AV-SIG News .............................................. Nancy Sefcrian 6 The Design Page for W.A.P .................................. Jay Rohr 42 Commercial Classifieds, Job Mart .......................................... 7 MacNovice Column: Word Processing .... Ralph J. Begleiter 47 * WAP Calendar, SIG News ..................................................... 8 Developer's View: The Great Apple Lawsuit.. ..... Bill Hole 50• WAP Hotline............................................................. ............. 9 Macintosh Bits & Bytes ............................... Lynn R. Trusal 52 Q & A ............................... Robert C. Platt & Bruce F. Field 10 Macinations 3 .................................................. Robb Wolov 56 Using -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

The Effects of a Press Release and Newspaper Coverage on Perceived Trustworthiness

Journal of Behavioral Public Administration Vol 1(1), pp. 1-10 DOI: 10.30636/jbpa.11.16 Breaking bad news without breaking trust: The effects of a press release and newspaper coverage on perceived trustworthiness Stephan Grimmelikhuijsen*, Femke de Vries†, Wilte Zijlstra‡ Abstract: Can a government agency mitigate the negative effect of “bad news” on public trust? To answer this question, we carried out a baseline survey to measure public trust five days before a major press release in- volving bad news about an error committed by an independent regulatory agency in the Netherlands. Two days after the agency’s press release, we carried out a survey experiment to test the effects on public trust of the press release itself as well as related newspaper articles. Results show that the press release had no nega- tive effect on trustworthiness, which may be because the press release “steals thunder” (i.e. breaks the bad news before the news media discovered it) and focuses on a “rebuilding strategy” (i.e. offering apologies and focusing on future improvements). In contrast, the news articles mainly focused on what went wrong, which affected the competence dimension of trust but not the other dimensions (benevolence and integrity). We con- clude that strategic communication by an agency can break negative news to people without necessarily break- ing trust in that agency. And although effects of negative news coverage on trustworthiness were observed, the magnitude of these effects should not be overstated. Keywords: Public trust, News media, Regulation, Strategic communication, Survey experiment any scholars in public administration and Slothuus & De Vreese, 2010) and how crisis com- M communication acknowledge the im- munication affects organizational reputations (e.g. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE SELF-PERCEPTION OF VIDEO GAME JOURNALISM: INTERVIEWS WITH GAMES WRITERS REGARDING THE STATE OF THE PROFESSION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Severin Justin Poirot Norman, Oklahoma 2019 THE SELF-PERCEPTION OF VIDEO GAME JOURNALISM: INTERVIEWS WITH GAMES WRITERS REGARDING THE STATE OF THE PROFESSION A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE GAYLORD COLLEGE OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION BY Dr. David Craig, Chair Dr. Eric Kramer Dr. Jill Edy Dr. Ralph Beliveau Dr. Julie Jones © Copyright by SEVERIN JUSTIN POIROT 2019 All Rights Reserved. iv Acknowledgments I’ve spent a lot of time and hand wringing wondering what I was going to say here and whom I was going to thank. First of all I’d like to thank my committee chair Dr. David Craig. Without his guidance, patience and prayers for my well-being I don’t know where I would be today. I’d like to also thank my other committee members: Dr. Eric Kramer, Dr. Julie Jones, Dr. Jill Edy, and Dr. Ralph Beliveau. I would also like to thank former member Dr. Namkee Park for making me feel normal for researching video games. Second I’d like to thank my colleagues at the University of Oklahoma who were there in the trenches with me for years: Phil Todd, David Ferman, Kenna Griffin, Anna Klueva, Christal Johnson, Jared Schroeder, Chad Nye, Katie Eaves, Erich Sommerfeldt, Aimei Yang, Josh Bentley, Tara Buehner, Yousuf Mohammad and Nur Uysal. I also want to extend a special thanks to Bryan Carr, who possibly is a bigger nerd than me and a great help to me in finishing this study. -

Protecting Citizen Journalists: Why Congress Should Adopt a Broad Federal Shield Law

YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW Protecting Citizen Journalists: Why Congress Should Adopt a Broad Federal Shield Law Stephanie B. Turner* INTRODUCTION On August 1, 20o6, a federal district judge sent Josh Wolf, a freelance video journalist and blogger, to prison.' Wolf, a recent college graduate who did not work for a mainstream media organization at the time, captured video footage of an anti-capitalist protest in California and posted portions of the video on his blog.2 As part of an investigation into charges against protestors whose identi- ties were unknown, federal prosecutors subpoenaed Wolf to testify before a grand jury and to hand over the unpublished portions of his video.' Wolf re- fused to comply with the subpoena, arguing that the First Amendment allows journalists to shield their newsgathering materials.4 The judge disagreed, and, as * Yale Law School, J.D. expected 2012; Barnard College, B.A. 2009. Thank you to Adam Cohen for inspiration; to Emily Bazelon, Patrick Moroney, Natane Single- ton, and the participants of the Yale Law Journal-Yale Law & Policy Review student scholarship workshop for their helpful feedback on earlier drafts; and to Rebecca Kraus and the editors of the Yale Law & Policy Review for their careful editing. 1. See Order Finding Witness Joshua Wolf in Civil Contempt and Ordering Con- finement at 2, In re Grand Jury Proceedings to Joshua Wolf, No. CR 06-90064 WHA (N.D. Cal. 2006); Jesse McKinley, Blogger Jailed After Defying Court Orders, N.Y. TIMES, Aug. 2, 2006, at A15. 2. For a detailed description of the facts of this case, see Anthony L. -

How the Imperial Mode of Living Prevents a Good Life for All for a Good Life the Imperial Mode of Living Prevents – How Researchers and Activists

I.L.A. Kollektiv I.L.A. Kollektiv Today it feels like everybody is talking about the problems and crises of our times: the climate and resource crisis, Greece’s permanent socio-political crisis or the degrading exploitative practices of the textile industry. Many are aware of the issues, yet little AT THE EXPENSE seems to change. Why is this? The concept of the imperial mode of living explains why, in spite of increasing injustices, no long-term alternatives have managed to succeed and a socio-ecological transformation remains out of sight. This text introduces the concept of an imperial mode of living and explains how our OF OTHERS? current mode of production and living is putting both people and the natural world under strain. We shine a spotlight on various areas of our daily lives, including food, mobility and digitalisation. We also look at socio-ecological alternatives and approaches How the imperial mode of living to establish a good life for everyone – not just a few. prevents a good life for all The non-pro t association Common Future e.V. from Göttingen is active in a number of projects focussing on global justice and socio-ecological business approaches. From April to May , the association organised the I.L.A. Werkstatt (Imperiale Lebensweisen – Ausbeutungsstrukturen im . Jahrhundert/ Imperial Modes of Living – Structures of Exploitation in the st Century). Out of this was borne the interdisciplinary I.L.A. Kollektiv, consisting of young – How the imperial mode of living prevents a good life for all for a good life the imperial mode of living prevents – How researchers and activists. -

Analysing the Changing Trajectory of South Korea's ICT Business

Analysing the Changing Trajectory of South Korea’s ICT Business Environment Nigel Callinan Thesis presented for the award of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisors: Professor Bernadette Andreosso & Dr. Mikael Fernström University of Limerick Submitted to the University of Limerick November 2014 Declaration I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctor of Philosophy is entirely my own work, that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ___________________________________ I.D No: 10142886 Date: Monday 10th November 2014 2 Abstract This thesis aims to provide a new perspective on the development of South Korea’s Information and Communications Technologies (ICT) Business Environment by taking a cross-disciplinary look at the area. Most studies on this subject have tended to remain within the boundaries of a single discipline. In this study, an interdisciplinary approach is taken to trace more of the paths that have influenced the development. This will provide a better understanding of the area and this insight should make it easier for any prospective organisation hoping to enter the Korean market to be successful. In little over two generations, South Korea has transformed from being one of the poorest countries in the world into a global business leader. Currently, Information Technology products are at the forefront of exports from the country and the world’s largest electronics company hails from a city just south of Seoul. -

The Press Release: Do TV and Newspaper Editors See Eye to Eye?

Public Relations Journal Vol. 5, No. 2, Spring 2011 ISSN 1942-4604 © 2011 Public Relations Society of America The Press Release: Do TV and Newspaper Editors See Eye to Eye? Reginald F. Moody In an effort to expand and compare results with a 2008 study of newspaper editors, this research asked the following: Do TV assignment editors have similar preferences for writing style in press releases as do their newspaper counterparts, or are they inclined to respond differently, owing to the demands of TV audiences and the characteristics of the broadcast medium? Results of this experiment indicate that TV assignment editors are just as likely as newspaper editors to use all or part of press releases written in either the inverted pyramid style or narrative style. However, the two have mixed opinions as to which writing style produces a more interesting and enjoyable, more informative, clearer and more understandable and more credible press release. The author discusses how public relations students and professionals can benefit from this disparity of response between TV assignment editors and newspaper editors in the acceptance or rejection of news releases based on writing style. The notion that newspaper editors are more likely to choose a press release written in a narrative style over one written in an inverted-pyramid style was mixed at best when viewed from the surface of an experiment conducted in 2008 of newspaper editors across the American heartland. Nonetheless, writing style was seen as having an unquestionable link to an editor’s assessment of certain press release characteristics, such as whether a release was found to be more interesting and enjoyable, more informative, clearer and more understandable and more credible.