Elastic Energy Storage in the Mantis Shrimp's Fast Predatory Strike

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning in Stomatopod Crustaceans

International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 2006, 19 , 297-317. Copyright 2006 by the International Society for Comparative Psychology Learning in Stomatopod Crustaceans Thomas W. Cronin University of Maryland Baltimore County, U.S.A. Roy L. Caldwell University of California, Berkeley, U.S.A. Justin Marshall University of Queensland, Australia The stomatopod crustaceans, or mantis shrimps, are marine predators that stalk or ambush prey and that have complex intraspecific communication behavior. Their active lifestyles, means of predation, and intricate displays all require unusual flexibility in interacting with the world around them, imply- ing a well-developed ability to learn. Stomatopods have highly evolved sensory systems, including some of the most specialized visual systems known for any animal group. Some species have been demonstrated to learn how to recognize and use novel, artificial burrows, while others are known to learn how to identify novel prey species and handle them for effective predation. Stomatopods learn the identities of individual competitors and mates, using both chemical and visual cues. Furthermore, stomatopods can be trained for psychophysical examination of their sensory abilities, including dem- onstration of color and polarization vision. These flexible and intelligent invertebrates continue to be attractive subjects for basic research on learning in animals with relatively simple nervous systems. Among the most captivating of all arthropods are the stomatopod crusta- ceans, or mantis shrimps. These marine creatures, unfamiliar to most biologists, are abundant members of shallow marine ecosystems, where they are often the dominant invertebrate predators. Their common name refers to their method of capturing prey using a folded, anterior raptorial appendage that looks superficially like the foreleg of a praying mantis. -

Myogenesis of Malacostraca – the “Egg-Nauplius” Concept Revisited Günther Joseph Jirikowski1*, Stefan Richter1 and Carsten Wolff2

Jirikowski et al. Frontiers in Zoology 2013, 10:76 http://www.frontiersinzoology.com/content/10/1/76 RESEARCH Open Access Myogenesis of Malacostraca – the “egg-nauplius” concept revisited Günther Joseph Jirikowski1*, Stefan Richter1 and Carsten Wolff2 Abstract Background: Malacostracan evolutionary history has seen multiple transformations of ontogenetic mode. For example direct development in connection with extensive brood care and development involving planktotrophic nauplius larvae, as well as intermediate forms are found throughout this taxon. This makes the Malacostraca a promising group for study of evolutionary morphological diversification and the role of heterochrony therein. One candidate heterochronic phenomenon is represented by the concept of the ‘egg-nauplius’, in which the nauplius larva, considered plesiomorphic to all Crustacea, is recapitulated as an embryonic stage. Results: Here we present a comparative investigation of embryonic muscle differentiation in four representatives of Malacostraca: Gonodactylaceus falcatus (Stomatopoda), Neocaridina heteropoda (Decapoda), Neomysis integer (Mysida) and Parhyale hawaiensis (Amphipoda). We describe the patterns of muscle precursors in different embryonic stages to reconstruct the sequence of muscle development, until hatching of the larva or juvenile. Comparison of the developmental sequences between species reveals extensive heterochronic and heteromorphic variation. Clear anticipation of muscle differentiation in the nauplius segments, but also early formation of longitudinal trunk musculature independently of the teloblastic proliferation zone, are found to be characteristic to stomatopods and decapods, all of which share an egg-nauplius stage. Conclusions: Our study provides a strong indication that the concept of nauplius recapitulation in Malacostraca is incomplete, because sequences of muscle tissue differentiation deviate from the chronological patterns observed in the ectoderm, on which the egg-nauplius is based. -

New Insights Into Loss and Reacquisition of Larval Stages Revealed by Heterochrony Analysis Günther Joseph Jirikowski1*, Carsten Wolff2 and Stefan Richter1

Jirikowski et al. EvoDevo 2015, 6:4 http://www.evodevojournal.com/content/6/1/4 RESEARCH Open Access Evolution of eumalacostracan development —new insights into loss and reacquisition of larval stages revealed by heterochrony analysis Günther Joseph Jirikowski1*, Carsten Wolff2 and Stefan Richter1 Abstract Background: Within Malacostraca (Crustacea), direct development and development through diverse forms of larvae are found. Recent investigations suggest that larva-related developmental features have undergone heterochronic evolution in Malacostraca. In the light of current phylogenetic hypotheses, the free-swimming nauplius larva was lost in the lineage leading to Malacostraca and evolved convergently in the malacostracan groups Dendrobranchiata and Euphausiacea. Here we reconstruct the evolutionary history of eumalacostracan (Malacostraca without Phyllocarida) development with regard to early appendage morphogenesis, muscle and central nervous system development, and determine the heterochronic transformations involved in changes of ontogenetic mode. Results: Timing of 33 developmental events from the different tissues was analyzed for six eumalacostracan species (material for Euphausiacea was not available) and one outgroup, using a modified version of Parsimov-based genetic inference (PGi). Our results confirm previous suggestions that the event sequence of nauplius larva development is partly retained in embryogenesis of those species which do not develop such a larva. The ontogenetic mode involving a nauplius larva was likely replaced by direct development in the malacostracan stem lineage. Secondary evolution of the nauplius larva of Dendrobranchiata from this ancestral condition, involved only a very small number of heterochronies, despite the drastic change of life history. In the lineage leading to Peracarida, timing patterns of nauplius-related development were lost. -

Ultraviolet Filters in Stomatopod Crustaceans: Diversity, Ecology and Evolution Michael J

© 2015. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | The Journal of Experimental Biology (2015) 218, 2055-2066 doi:10.1242/jeb.122036 RESEARCH ARTICLE Ultraviolet filters in stomatopod crustaceans: diversity, ecology and evolution Michael J. Bok*,§, Megan L. Porter‡ and Thomas W. Cronin ABSTRACT 1988; Marshall et al., 1991a) and at least five receptors sensitive to Stomatopod crustaceans employ unique ultraviolet (UV) optical filters various spectral ranges of ultraviolet (UV) light (Kleinlogel and in order to tune the spectral sensitivities of their UV-sensitive Marshall, 2009; Marshall and Oberwinkler, 1999). Underlying photoreceptors. In the stomatopod species Neogonodactylus oerstedii, these diverse visual sensitivities is an array of optical and retinal we previously found four filter types, produced by five distinct structural modifications (Horridge, 1978; Marshall et al., 1991a; mycosporine-like amino acid pigments in the crystalline cones of their Schiff et al., 1986), the expression of a great number of opsins specialized midband ommatidial facets. This UV-spectral tuning array resulting in the most visual pigments yet described in a single eye produces receptors with at least six distinct spectral sensitivities, (Cronin and Marshall, 1989b; Cronin et al., 1993; Porter et al., 2009, despite expressing only two visual pigments. Here, we present a 2013), and the tuning of spectral sensitivity via serial filtering broad survey of these UV filters across the stomatopod order, effects due to more distal visual pigments as well as photostable examining their spectral absorption properties in 21 species from colored pigments (Cronin and Marshall, 1989a; Cronin et al., seven families in four superfamilies. We found that UV filters are 1994a,b, 2014; Marshall, 1988; Marshall et al., 1991b; Porter et al., present in three of the four superfamilies, and evolutionary character 2010). -

Evolution Der Muskelentwicklung Der Malacostraca (Crustacea

Evolution der Muskelentwicklung der Malacostraca (Crustacea) – Vergleichende Untersuchung ausgewählter Vertreter vor dem Hintergrund embryonaler und larvaler Transformationen Kumulative Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) Am Lehrstuhl für Allgemeine und Spezielle Zoologie des Instituts für Biowissenschaften an der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Rostock vorgelegt von Günther Joseph Jirikowski, geboren am 24.11.1983 in Ulm / Baden-Württemberg Rostock, Februar 2015 1 2 Gutachter: 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Stefan Richter, Allgemeine und Spezielle Zoologie, Institut für Biowissenschaften, Universität Rostock 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Gerhard Scholtz, Vergleichende Zoologie, Institut für Biologie, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Datum der Einreichung: 20. Februar 2015 Datum der Verteidigung: 17. April 2015 3 4 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitende Zusammenfassung ................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Übersicht .............................................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.2 Die Malacostraca .............................................................................................................................................................. 9 1.3 Einauplius und kryptische Larvalentwicklung ................................................................................................... -

Stomatopod Crustaceans from Mayotte Island (Crustacea, Hoplocarida)

STOMATOPOD CRUSTACEANS FROM MAYOTTE ISLAND (CRUSTACEA, HOPLOCARIDA) Joseph Poupin, Regis Cleva, Jean-Marie Bouchard, Vincent Dinhut, and Jacques Dumas Atoll Research Bulletin No. 624 ⬧ 6 June 2019 Washington, D.C. All statements made in papers published in the Atoll Research Bulletin are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Smithsonian Institution or of the editors of the bulletin. Articles submitted for publication in the Atoll Research Bulletin should be original papers and must be made available by authors for open access publication. Manuscripts should be consistent with the “Author Formatting Guidelines for Publication in the Atoll Research Bulletin.” All submissions to the bulletin are peer reviewed and, after revision, are evaluated prior to acceptance and publication through the publisher’s open access portal, Open SI (https://opensi.si.edu). Published by SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION SCHOLARLY PRESS P.O. Box 37012, MRC 957 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 https://scholarlypress.si.edu/ The rights to all text and images in this publication are owned either by the contributing authors or by third parties. Fair use of materials is permitted for personal, educational, or noncommercial purposes. Users must cite author and source of content, must not alter or modify the content, and must comply with all other terms or restrictions that may be applicable. Users are responsible for securing permission from a rights holder for any other use. ISSN: 0077-5630 (online) CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................................. -

Elena Tricarico Editors Social Recognition in Invertebrates the Knowns and the Unknowns Social Recognition in Invertebrates Laura Aquiloni · Elena Tricarico Editors

Laura Aquiloni · Elena Tricarico Editors Social Recognition in Invertebrates The Knowns and the Unknowns Social Recognition in Invertebrates Laura Aquiloni · Elena Tricarico Editors Social Recognition in Invertebrates The Knowns and the Unknowns 1 3 Editors Laura Aquiloni Elena Tricarico Department of Biology Department of Biology University of Florence University of Florence Florence Florence Italy Italy ISBN 978-3-319-17598-0 ISBN 978-3-319-17599-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-17599-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015936295 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Learning in Stomatopod Crustaceans

International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 2006, 19, 297-317. Copyright 2006 by the International Society for Comparative Psychology Learning in Stomatopod Crustaceans Thomas W. Cronin University of Maryland Baltimore County, U.S.A. Roy L. Caldwell University of California, Berkeley, U.S.A. Justin Marshall University of Queensland, Australia The stomatopod crustaceans, or mantis shrimps, are marine predators that stalk or ambush prey and that have complex intraspecific communication behavior. Their active lifestyles, means of predation, and intricate displays all require unusual flexibility in interacting with the world around them, imply- ing a well-developed ability to learn. Stomatopods have highly evolved sensory systems, including some of the most specialized visual systems known for any animal group. Some species have been demonstrated to learn how to recognize and use novel, artificial burrows, while others are known to learn how to identify novel prey species and handle them for effective predation. Stomatopods learn the identities of individual competitors and mates, using both chemical and visual cues. Furthermore, stomatopods can be trained for psychophysical examination of their sensory abilities, including dem- onstration of color and polarization vision. These flexible and intelligent invertebrates continue to be attractive subjects for basic research on learning in animals with relatively simple nervous systems. Among the most captivating of all arthropods are the stomatopod crusta- ceans, or mantis shrimps. These marine creatures, unfamiliar to most biologists, are abundant members of shallow marine ecosystems, where they are often the dominant invertebrate predators. Their common name refers to their method of capturing prey using a folded, anterior raptorial appendage that looks superficially like the foreleg of a praying mantis. -

RESEARCH ARTICLE Comparative Spring Mechanics in Mantis Shrimp

1317 The Journal of Experimental Biology 216, 1317-1329 © 2013. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd doi:10.1242/jeb.078998 RESEARCH ARTICLE Comparative spring mechanics in mantis shrimp S. N. Patek1,*, M. V. Rosario1 and J. R. A. Taylor2 1Department of Biology, Organismic and Evolutionary Graduate Program, University of Massachusetts Amherst, MA 01003, USA and 2Department of Biology, Indiana University-Purdue University, Fort Wayne, IN 46805-1499, USA *Author for correspondence ([email protected]) SUMMARY Elastic mechanisms are fundamental to fast and efficient movements. Mantis shrimp power their fast raptorial appendages using a conserved network of exoskeletal springs, linkages and latches. Their appendages are fantastically diverse, ranging from spears to hammers. We measured the spring mechanics of 12 mantis shrimp species from five different families exhibiting hammer- shaped, spear-shaped and undifferentiated appendages. Across species, spring force and work increase with size of the appendage and spring constant is not correlated with size. Species that hammer their prey exhibit significantly greater spring resilience compared with species that impale evasive prey (ʻspearersʼ); mixed statistical results show that species that hammer prey also produce greater work relative to size during spring loading compared with spearers. Disabling part of the spring mechanism, the ʻsaddleʼ, significantly decreases spring force and work in three smasher species; cross-species analyses show a greater effect of cutting the saddle on the spring force and spring constant in species without hammers compared with species with hammers. Overall, the study shows a more potent spring mechanism in the faster and more powerful hammering species compared with spearing species while also highlighting the challenges of reconciling within-species and cross-species mechanical analyses when different processes may be acting at these two different levels of analysis. -

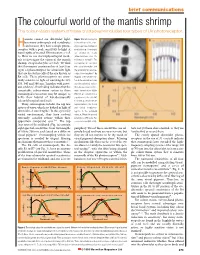

The Colourful World of the Mantis Shrimp the Colour-Vision System of These Crustaceans Includes Four Types of UV Photoreceptor

brief communications The colourful world of the mantis shrimp The colour-vision system of these crustaceans includes four types of UV photoreceptor. umans cannot see ultraviolet light, Figure 1 R8 photoreceptors but many arthropods and vertebrates in the midband of the stom- Hcan because they have a single photo- atopod eye have multiple UV receptor with a peak sensitivity to light at sensitivities a, Stomatopod wavelengths of around 350 nanometres (ref. eye showing the clearly 1). Here we use electrophysiological meth- defined midband, rows 1 to ods to investigate the vision of the mantis 6 (dorsal to ventral)4,5. The shrimp, Neogonodactylus oerstedii. We find top four rows are concerned that this marine crustacean has at least four with colour information, and types of photoreceptor for ultraviolet light the remaining two are spe- that are located in cells of the eye known as cialized for polarization2,5. b, R8 cells. These photoreceptors are maxi- Diagram of the photorecep- mally sensitive to light of wavelengths 315, tors in the six midband rows 330, 340 and 380 nm. Together with previ- and the peripheral retinae. ous evidence2, this finding indicates that the R8 cells are coloured. Chro- remarkable colour-vision system in these matic channels from 400 to stomatopod crustaceans may be unique, as 700 nm are contained in a befits their habitat of kaleidoscopically population of cells called R1 colourful tropical coral reefs. to R7 (ref. 4). VH and DH are Many stomatopods inhabit the top few representatives of the dorsal metres of water, which are bathed in light of and ventral hemisphere ultraviolet-A wavelengths3. -

Neuroarchitecture of the Color and Polarization Vision System of the Stomatopod Haptosquilla

THE JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE NEUROLOGY 467:326–342 (2003) Neuroarchitecture of the Color and Polarization Vision System of the Stomatopod Haptosquilla SONJA KLEINLOGEL,1* N. JUSTIN MARSHALL,1 JULIA M. HORWOOD,2 AND MIKE F. LAND2 1Vision, Touch, and Hearing Research Centre, Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane QLD 4072, Australia 2Sussex Centre for Neuroscience, School of Biological Sciences, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton, East Sussex BN1 9QG, United Kingdom ABSTRACT The apposition compound eyes of stomatopod crustaceans contain a morphologically distinct eye region specialized for color and polarization vision, called the mid-band. In two stomatopod superfamilies, the mid-band is constructed from six rows of enlarged ommatidia containing multiple photoreceptor classes for spectral and polarization vision. The aim of this study was to begin to analyze the underlying neuroarchitecture, the design of which might reveal clues how the visual system interprets and communicates to deeper levels of the brain the multiple channels of information supplied by the retina. Reduced silver methods were used to investigate the axon pathways from different retinal regions to the lamina gangli- onaris and from there to the medulla externa, the medulla interna, and the medulla termi- nalis. A swollen band of neuropil—here termed the accessory lobe—projects across the equator of the lamina ganglionaris, the medulla externa, and the medulla interna and represents, structurally, the retina’s mid-band. Serial semithin and ultrathin resin sections were used to reconstruct the projection of photoreceptor axons from the retina to the lamina ganglionaris. The eight axons originating from one ommatidium project to the same lamina cartridge. -

The Evolutionary History of Stomatopoda (Crustacea: Malacostraca) Inferred from Molecular Data

The evolutionary history of Stomatopoda (Crustacea: Malacostraca) inferred from molecular data Cara Van Der Wal1,2, Shane T. Ahyong2,3, Simon Y.W. Ho1 and Nathan Lo1 1 School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia 2 Australian Museum, Sydney, Australia 3 School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Kensington, Australia ABSTRACT The crustacean order Stomatopoda comprises seven superfamilies of mantis shrimps, found in coastal waters of the tropics and subtropics. These marine carnivores bear notable raptorial appendages for smashing or spearing prey. We investigated the evolutionary relationships among stomatopods using phylogenetic analyses of three mitochondrial and two nuclear markers. Our analyses recovered the superfamily Gonodactyloidea as polyphyletic, with Hemisquilla as the sister group to all other extant stomatopods. A relaxed molecular clock, calibrated by seven fossil-based age constraints, was used to date the origin and major diversification events of stomatopods. Our estimates suggest that crown-group stomatopods (Unipeltata) diverged from their closest crustacean relatives about 340 Ma (95% CRI [401–313 Ma]). We found that the specialized smashing appendage arose after the spearing appendage ∼126 Ma (95% CRI [174–87 Ma]). Ancestral state reconstructions revealed that the most recent common ancestor of extant stomatopods had eyes with six midband rows of hexagonal ommatidia. Hexagonal ommatidia are interpreted as plesiomorphic in stomatopods, and this is consistent with the malacostracan ground-plan. Our study provides insight into the evolutionary timescale and systematics of Stomatopoda, although further work is required to resolve with confidence the phylogenetic relationships among its Submitted 25 July 2017 superfamilies.