Knowledge of Causes-4-11-12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weighing Falling Bodies. Galileo's Thought Experiment in The

Weighing Falling Bodies. Galileo’s Thought Experiment in the Development of his Dynamical Thinking. Maarten Van Dyck Centre for Logic and Philosophy of Science Centre for History of Science Ghent University [email protected] {The author is research assistant of the Fund for Scientific Research (FWO) – Flanders} 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Tim De Mey, without whom I would have never plunged so deep in Galileo’s thought experiment; Paolo Palmieri, who made the invaluable suggestion that I should have a look at the postils to Rocco , and whose comments on a first version of this paper helped to significantly improve both its contents and presentation; and Sabina Leonelli for her much appreciated assistance in translating the Italian fragments from the postils to Rocco. 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction: The intelligibility of dynamics – the dynamics of intelligibility PART I – Understanding weight as a dynamic factor: Ambiguities 2. La bilancetta : Understanding mixtures and transforming gravities 2.a Solving the crown problem 2.b Balancing mixtures and speeds 3. De motu : Attempts at an Archimedean natural philosophy 3.a The dynamics of De motu 3.b From equal volumes to unit volumes 4. De motu : Introducing the thought experiment 4.a A hidden assumption 4.b The dynamical conundrum 5. Discorso : The impotence of specific gravity as a dynamic factor 5.a Moment and absolute weight 5.b Moment and specific weight 5.c The extrapolation argument PART II – Understanding weight as a dynamic factor: Towards a resolution 6. Postille a Roco : Rethinking the thought experiment 6.a Re-presenting the thought experiment 6.b Resolving the dynamical conundrum 7. -

In the Later Philosophy of Paul Feyerabend

Durham E-Theses Pluralism and the 'Problem of Reality' in the Later Philosophy of Paul Feyerabend KIDD, IAN,JAMES How to cite: KIDD, IAN,JAMES (2010) Pluralism and the 'Problem of Reality' in the Later Philosophy of Paul Feyerabend, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/864/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Kidd Pluralism and the ‘Problem of Reality’ in the Later Philosophy of Paul Feyerabend Abstract Feyerabend’s later philosophy was a sustained defence of cultural and epistemic diversity. After Against Method (1975) Feyerabend argued that his rejection of methodological monism challenged the presumed unity and superiority of scientific knowledge and practices. His later philosophy was therefore dedicated to a reassessment of the merits of a wide range of ‘non-scientific’ traditions present throughout non-Western indigenous cultures. -

Understanding the Progress of Science

Understanding the Progress of Science C. D. McCoy 30 May 2018 The central problem of epistemology has always been and still is the problem of the growth of knowledge. And the growth of knowledge can be studied best by studying the growth of scientific knowledge. —(Popper, 2002b, xix) Merely fact-minded sciences make merely fact-minded people. —(Husserl, 1970, 6) The growth of human knowledge is realized most dramatically in the growth of scientific knowledge. What we have come to know through science about the workings of our human bodies and the workings of heavenly bodies, among much else, astounds, especially in comparison to our accumulating knowledge of the commonplace and everyday. Impressed by the evident epistemic progress made by science, many philosophers during the 20th century thought that studying how scientific knowledge increases is a crucial task of epistemological inquiry, and, indeed, the progress of science has been a topic of considerable interest. Yet, eventually, late in the century, attention waned and for the most part shifted to other tasks. Recently, however, a provocative article by Bird has re-ignited philosophical interest in the topic of scientific progress (Bird, 2007). Bird criticizes what he takes to have been the most prominent accounts advanced in the 20th century and presses for what he views as a venerable but lately overlooked one. He claims that realist philosophers of science have often presumed that truth is the goal of science and progress to be properly characterized by an accu- mulation of truth or truths, and notes that anti-realists have often rejected truth as a goal of science and characterized progress in terms of, among other things, “problem-solving effectiveness.”1 He criticizes the former for overlooking the relevance of justification to progress and the latter for giving up on truth. -

Philosophy in the Nineteenth Century

GEORGEMASON UNIVERSITY UNIVERSllY LIBRARIES THE OXFORD HANDBOOK OF GERMAN PHILOSOPHY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY ............................................................................................................................................................... Edited by MICHAEL N. FORSTER and KRISTIN GJESDAL OXFORD U N lV ERSITY PR ESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Great Clarendon Street , Oxford, o:u 6oP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a depart ment of the t:niver,11r of Chford It furthers the University's obJective of excellence m n·s~·arch, s.:hol.1r,h1r , . and edu cation by publishing wor ldwide . Oxford is a regmereJ trade mJrk ,,t Oxford University Press m the IJK and in certain other countnc, © The several contribu tors 1015 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition pub!t,hed 10 2015 Impress ion 1 All rights reserved . No part of this publication may be rerroJuceJ. stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any mea ns, without the prior permiss ion in writing of Oxford University Press, or as npreHl y pcrm1tteJ by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the arpropr1ate repr oi:raph1,, rights organi zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outsi de th e swre of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford tJ111vers1ty Pre,,, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impo se this same condit ion on any .icqu irt'r Published in the United States of America by Oxford University l're,s 198 Madison Avenue , New York, NY wo16, United StJ tes of Amer tCJ British Library Cataloguing in Puhlication l>Jta Data availa ble Library of Congress Control Numher: 2014946121 ISBN 978- 0 -19-969654 - 3 Printed and boun d by CPI Gro up (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY Links to thud party websites are provided by Oxford in !(OOJ faith anJ for information only. -

1 What's So Special About Model Organisms?

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE What makes a model organism? AUTHORS Leonelli, Sabina; Ankeny, Rachel A. JOURNAL Endeavour DEPOSITED IN ORE 15 January 2015 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/20864 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication What’s So Special About Model Organisms? Rachel A. Ankeny* and Sabina Leonelli *Corresponding author: email: [email protected] , mailing address: School of History and Politics, Napier 423, University of Adelaide, Adelaide 5005 SA, Australia, telephone: +61-8-8303-5570, fax: +61-8-8303-3443. Abstract This paper aims to identify the key characteristics of model organisms that make them a specific type of model within the contemporary life sciences: in particular, we argue that the term “model organism” does not apply to all organisms used for the purposes of experimental research. We explore the differences between experimental and model organisms in terms of their material and epistemic features, and argue that it is essential to distinguish between their representational scope and representational target . We also examine the characteristics of the communities who use these two types of models, including their research goals, disciplinary affiliations, and preferred practices to show how these have contributed to the conceptualization of a model organism. We conclude that model organisms are a specific subgroup of organisms that have been standardized to fit an integrative and comparative mode of research, and that must be clearly distinguished from the broader class of experimental organisms. -

ICOHTEC NEWSLETTER O N 176, December 2020

ICOHTEC NEWSLETTER No 176, December 2020 www.icohtec.org Sound To Light System Sound Operated Lamp Switch Circuit The first real dedicated disco lights were invented in about 1968 when someone decided to control lighting using electronics (Transistors and Thyristors in those days, no silicon chips) the idea was to flash lamps to different frequencies, originally three channels. Basically one lamp would flash in time with the Bass frequency, one in time with the Middle and one in time with the Treble. For the first time Sound To Light was born. The sound of the light: https://youtu.be/vkVPXpSE_Us Newsletter of the International Committee for the History of Technology - ICOHTEC Editor: Francesco Gerali, The University of Oklahoma School of Library and Information Studies. Norman, OK, United States. Mail to [email protected] Newsletter of the International Committee for the History of Technology - ICOHTEC Editor: Francesco Gerali, 2020 IEEE Pugh Visiting Scholar, IEEE History Center, NJ, United States. Mail to [email protected] I. ICOHTEC I.1 26TH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY AND THE 48TH SYMPOSIUM OF ICOHTEC GO ONLINE I.2 MAURICE DAUMAS PRIZE - ICOHTEC’S ARTICLE PRIZE I.3 TURRIANO ICOHTEC PRIZE 2021 - CALL FOR SUBMISSIONS I.4 ICON II. PRIZES III. JOURNALS IV. E-SCHOL@RSHIP IN THE V. OPEN ACCESS VI. CALLS FOR MANUSCRIPTS VII. CALLS FOR PAPERS VIII. PLASTICIDADE, UMA HISTÓRIA DOS PLÁSTICOS EM PORTUGAL, A HISTORY OF PLASTICS IN PORTUGAL IX. JOBS, POSTDOCTORAL POSITIONS, AND RESEARCH FELLOWSHIPS X. JOIN ICOHTEC 1 I. ICOHTEC I.1 26th International Congress of History of Science and Technology and the 48th Symposium of ICOHTEC go online Dear Colleagues and Friends, Due to the risks of a real meeting, the organizers of the 26th International Congress of History of Science and Technology, ICHST (25 – 31 July 2021), decided to organize the conference online. -

Arc of the Data Scientific Universe Leslie HDSR

The Arc of the Data Scientific Universe A comment on Sabina Leonelli’s “Data Science in Times of Pand(dem)ic” David Leslie, The Alan Turing Institute [email protected] To be published in Harvard Data Science Review (Winter 2021) Abstract In this paper explore the scaffolding of normative assumptions that supports Sabina Leonelli’s implicit appeal to the values of epistemic integrity and the global public good that conjointly animate the ethos of responsible and sustainable data work in the context of COVID-19. Drawing primarily on the writings of sociologist Robert K. Merton, the thinkers of the Vienna Circle, and Charles Sanders Peirce, I make some of these assumptions explicit by telling a longer story about the evolution of social thinking about the normative structure of science from Merton’s articulation of his well-known norms—those of universalism, communism, organized skepticism, and disinterestedness—to the present. I show that while Merton’s norms and his intertwinement of these with the underlying mechanisms of democratic order provide us with an especially good starting point to explore and clarify the commitments and values of science, Leonelli’s broader, more context-responsive, and more holistic vision of the epistemic integrity of data scientific understanding, and her discernment of the global and biospheric scope of its moral-practical reach, move beyond Merton’s schema in ways that effectively draw upon important critiques. Stepping past Merton, I argue that a combination of situated universalism, methodological pluralism, strong objectivity, and unbounded communalism must guide the responsible and sustainable data work of the future. -

Aspects of Theory-Ladenness in Data-Intensive Science1

Aspects of theory-ladenness in data-intensive science1 Wolfgang Pietsch2 Munich Center for Technology in Society, TU München, Munich, Germany Abstract Recent claims, mainly from computer scientists, concerning a largely automated and model- free data-intensive science have been countered by critical reactions from a number of philosophers of science. The debate suffers from a lack of detail in two respects, regarding (i) the actual methods used in data-intensive science and (ii) the specific ways in which these methods presuppose theoretical assumptions. I examine two widely-used algorithms, classificatory trees and non-parametric regression, and argue that these are theory-laden in an external sense, regarding the framing of research questions, but not in an internal sense concerning the causal structure of the examined phenomenon. With respect to the novelty of data-intensive science, I draw an analogy to exploratory as opposed to theory-directed experimentation. 1. Introduction Over the past decade, computer scientists have claimed that a new scientific methodology has become possible through advances in information technology (e.g. Gray 2007). This approach is supposed to be data-driven, strongly inductive, and relatively theory-independent. The epistemology of such data-intensive science has recently emerged as a novel topic in philosophy of science. Generally, the reactions have been rather critical, often referring to the more or less trivial observation that some kind of theory-ladenness always occurs in scientific research. But, as I will argue, this means throwing the baby out with the bathwater, since interesting shifts in the role of theory can indeed be observed when examining specific methods employed in data-intensive science. -

Academic Philosopher of Science and Information Sabina Leonelli

DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY STUDIES STS Careers Podcast – Dr Emma Tobin talks to former BSc History, Philosophy and Social Studies of Science student, and current Professor of Philosophy and History of Science at the University of Exeter, Sabina Leonelli. Sabina graduated from the BSc in History, Philosophy and Social Studies of Science in 2000, before completing an MSc at LSE, going on to work as a research assistant to Hasok Chang at the Centre for the Philosophy of Natural and Social Science. She joined the University of Exeter in 2009, where she works to this day. ET Welcome to the STS Careers Podcast series. I’m Dr Emma Tobin, a philosopher of science here at STS, and I’m joined today by Dr Sabina Leonelli, who is a lecturer in the department of Sociology and Philosophy at the University of Exeter. Hi Sabina. SL Hi Emma. ET So thanks for joining us today in advance of your research seminar here at the department. What we wanted to do today is talk a little bit about careers in academia and ask you a little bit about your career path, how it went, some of the problems that you faced along the way and so on… and obviously some of the successes that you gained along the way. Can you tell us briefly what your career path has been. You started, obviously, with us as one of our undergraduate students here at STS. SL Sure. Right after that I was already thinking – I had a very strong inclination to do a PhD. -

Program Booklet

16th International Congress on Logic, Methodology and Philosophy of Science and Technology Bridging across academic cultures Faculty of Architecture, Czech Technical University in Prague Prague, Czech Republic 5–10 August 2019 Words of Welcome from the DLMPST/IUHPST Dear Logicians and Philosophers of Science, On behalf of the Division of Logic, Methodology and Philosophy of Science and Technology of the International Union of History and Philosophy of Science and Technology (DLMPST/IUHPST), we should like to welcome all fellow researchers and scholars in our fields to the XVI Congress on Logic, Methodology, and Philoso- phy of Science and Technology (CLMPST) and look forward to your joining us in Prague in August 2019. Our fields, logic and the philosophy of science and technology, traditionally form a nexus between disciplines, equally at home in the sciences, the humanities and the social sciences. As a consequence, many logicians and philosophers of science fre- quently act as mediators between disciplinary traditions and serve as translators of mutually unintelligible academic vernaculars. Thus the theme of the 2019 congress, “Bridging across academic cultures”, is central to the experience of many among us. The theme refers not only to the aforementioned academic cultures, so forcefully evoked in C. P. Snow’s 1959 Rede lecture, “The Two Cultures”, which celebrates its 60th anniversary in the year of our congress, but also to the highly topical cultural dif- ferences between various countries and regions around the globe. As the global repre- sentative of our fields, DLMPST/IUHPST seeks to enrich our scientific dialogue by including the voices of those traditionally underrepresented in our academic fields, be it due to geography, culture, ethnicity, or gender. -

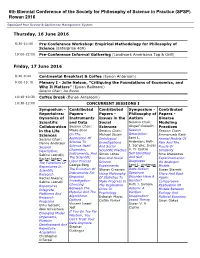

SPSP2016 Program

6th Biennial Conference of the Society for Philosophy of Science in Practice (SPSP) Rowan 2016 OpenConf Peer Review & Conference Management System Thursday, 16 June 2016 9:30-14:00 Pre-Conference Workshop: Empirical Methodology for Philosophy of Science (Enterprise 409) 19:00-22:00 Pre-Conference Informal Gathering (Landmark Americana Tap & Grill) Friday, 17 June 2016 8:30-9:00 Continental Breakfast & Coffee (Eynon Anteroom) 9:00-10:10 Plenary I - Julie Nelson, "Critiquing the Foundations of Economics, and Why It Matters" (Eynon Ballroom) Session Chair: Joe Rouse 10:10-10:30 Coffee Break (Eynon Anteroom) 10:30-12:00 CONCURRENT SESSIONS I Symposium - Contributed Contributed Symposium - Contributed Repertoires: Papers - Papers - Philosophy of Papers - Dynamics of Instruments Issues in the Autism Diverse Scientific and Data Social Session Chair: Modeling Collaboration Session Chair: Sciences Abigail Gosselin Practices in the Life Mieke Boon Session Chair: Session Session Chair: Sciences On The Michael Stuart Description: Emmanuele Ratti Jami L. Session Chair: Application Of Ontological Animal Models Of Anderson; Ruth Hanne Andersen Science To Investigations Pain And The J. Sample; Susan Session Science Itself: And Social Puzzle Of V. H. Castro Description: Chemistry, Scientific Practice Similarity Self Identities Sabina Leonelli; Instruments, And Simon Lohse Nina Atanasova And Self Rachel Ankeny The Scientific Bias And Social Experimentation Labor Process Diagnoses The Functions Of Science On Analogue George Borg Jami L. Anderson Repertoires In Experiments Models Does Autism Scientific The Evolution Of Sharon Crasnow Susan Sterrett Spectrum Research Instruments For Using Philosophy There And Back Disorder Have A Rachel Ankeny; Empirical Of Statistics To Again: Gender? Sabina Leonelli Investigation: Make Progress In Comparative Choosing Ruth J. -

Review of Sabina Leonelli's Data-Centric Biology

Manuscript Copyright The Philosophy of Science Association 2018. Preprint (not copyedited or formatted). Please use DOI when citing or quoting. DOI: 10.1086/697732 Sabina Leonelli, Data-Centric Biology: A Philosophical Study. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2016), 281 pp., $35.00 (paperback). Beckett Sterner School of Life Sciences Arizona State University E-mail: [email protected] Introduction The word “data” is everywhere in current discussions of science. How we store and share things people label “data” has become a central concern for the Open Science movement, for example, and the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health have invested billions of dollars in the creation of publicly accessible databases as a major new source of intellectual capital in science and industry. What is new here? Has there been a shift in what “data” means that is key to understanding the future of science? Sabina Leonelli’s new book, Data-Centric Biology: A Philosophical Study, argues for an important and fruitful answer outside the comfort zone of many philosophers. Along the way, she also delivers a range of valuable insights into the expanding efforts to standardize, automate, and communicate how scientists handle, share, reproduce, interpret, and store data. From the start, Leonelli rejects the idea that we can understand the significance of data for science in terms of intrinsic properties data possess as material traces of past processes. Similarly, the changes we’re seeing in science aren’t driven simply by revolutionary technologies or methods. “The real source of innovation in current biology is the attention paid to data handling and dissemination practices and the ways in which such practices mirror economic and political modes of interaction and decision making” (1).