The Case of Australian Christian Youth Festivals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

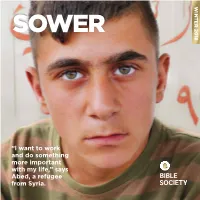

“I Want to Work and Do Something More Important with My Life,” Says Abed, a Refugee from Syria

WINTER 2018 SOWER “I want to work and do something more important with my life,” says Abed, a refugee from Syria. 1 A lamp to their feet A light to their path For long-time Bible Society the Flying Bible Man, who became chaplain to construction workers supporters Bill and Jocelyn Ross, a great asset. on a dam, Trevor Booth went the Bible really has proved to be “I’d go with Trevor in his plane with him to visit the workers. “He “a lamp to their feet and a light to and catch up with people on the had a good fi lm to show in the their path,” as they have navigated stations. I was fl ying with Trevor workmen’s mess service. On one the roads God has taken them. when the Bible Society made a occasion the sound system wasn’t After studying and marrying fi lm about his work in the East working – but it didn’t matter, in Canberra, Bill and Jocelyn Pilbara. What I remember the because Trevor narrated the fi lm! ministered for a few years in most about the fi lming was the He had shown the fi lm so many Albury, NSW, before moving to constant fl ies in our eyes! ... it was times, he knew the dialogue by the far north of Western Australia a wonderful experience” heart.” in 1970 and beginning a life-long When the Rosses moved to Trevor also assisted with the ministry there. Dampier, a Pilbara port town, Bill They began in the town of again engaged in patrols with Kununurra and the patrol district Trevor at several stations in the of the East Kimberley, with the West Pilbara, and Barrow Island. -

Annual Report Two Thousand & Fourteen Hillsong Church, Australia Hillsong Church Annual Report 2 Index

Annual Report Two Thousand & Fourteen Hillsong Church, Australia 2 Annual Report Hillsong Church Index Chairperson’s Report 4 The Church I Now See 5 Lead Pastor’s Report 6 General Manager’s Report 7 History 8 Church Services 10 Programs & Services 12 Children 14 Youth 16 Women 18 Young at Heart 20 Pastoral Care 22 Volunteers 24 Creative Arts 26 Worship 28 Conferences 30 Missions 32 Education 34 Local Community Services 36 Overseas Aid & Development 42 The Hillsong Foundation 46 Two Thousand & Fourteen Two Our Board 48 Financial Reports 51 “I see a church Governance 58 that beckons WELCOME HOME to every man, woman and child that walks through the doors.” – Brian Houston (The Church I Now See) 3 Chairperson’s Report Brian & Bobbie Houston As we reflect on the year past, we can truly thank God for His We have now been holding Hillsong Conference since 1986 unwavering goodness and love for humanity. God specialises with the mission: Championing the cause of local churches in lifting people out of tragedy and pain, rebuilding hope and everywhere. With over 22,000 attendees and 19 Christian restoring us to a friendship with Him. denominations represented we celebrate the diversity of the expressions of our faith and gather around the common We as a church are privileged to play our role in seeing lives understanding that a healthy local church can make a positive impacted through the Gospel of Jesus Christ. At Hillsong impact in its community. Church, hundreds of people make a decision to follow Christ each week, a foundational step on a journey of personal It is with this understanding we are enthusiastic about freedom and understanding. -

February 2004

VOLUME 31/1 FEBRUARY 2004 “Do you not give the horse his strength or clothe his neck with a flowing mane?” Job 39:19 faith in focus Volume 31/1, February 2004 CONTENTS Editorial Whose party are you going to? Uncovering a very present danger 3 It was some years ago that a minister was overhearing several colleagues at a minister’s conference speaking about several high-powered revival meetings Not satisfied with Jesus? When faith is not alone 7 they had experienced. They spoke in glowing terms of how warmly they felt and how much everyone there shared a wonderful spiritual unity. Sons of encouragement 8 This minister shared with them his own experience of a meeting he had come World News 9 from the night before he flew over. He detailed the feelings he had when over Breakthrough 40,000 sang the same songs, held hands, and came away with a truly The lesson in life 11 unforgetable event. Missions in focus His colleagues now were completely captivated by his story. This was something Growing the church in Karamoja extraordinary. And to hear all this from this man who otherwise you would think Prayer points RCNZ food aid to Malawi 12 was the last to be open to such a move of the Spirit! They had to ask him who was the cause for this incredible time. Which special person’s meeting was it? Surfing the Net The upside & downside of the Internet 15 “Oh,” the minister replied, “it was a Paul McCartney concert.” Naturally, those ministers felt somewhat taken in. -

Love Your Global Neighbour

theadvocate.tv DECEMBER 2018 IN CONVERSATION Finding Faith duo, Andrew Tierney “Perhaps we need to keep challenging ourselves about the and Tim Dunfield talk about their passion for writing power of un-deciding to open ourselves to an even bigger songs of worship and their debut album. PAGE 12 >> decision – an even bigger ‘yes’.” SIMON ELLIOTT PAGE 13>> 3 Holy secularism Christmas is not what it used to be >> 4 Royal Commission Scheme provides support for childhood abuse >> Photo: Shane Burrell Risanya can grow enough food to feed her family and sell at the market for an income, thanks to the support of good neighbours in Australia. Love your global 10 Asia Bibi freed Christian mother released neighbour from Pakistan’s death row >> Baptist World Aid Australia, in conjunction with A Just Cause, has launched a efforts leading up to the next new report: The Global Neighbour Index. The report examines: Is Australia a good Federal Election, where Baptists global neighbour?, taking seriously Jesus’ call to “love your neighbour as yourself”. around the country will organise electorate forums using the report as a guide to converse Committed to Against its most-developed peers, government and the broader “It is not often that we get to with candidates. Australia was ranked 11th out of community to participate influence the policymakers of The index uses ten indicators being honest, 20 overall in a report that graded responsibly in seeking change. our nation in such a specific and to consider complex issues such transparent and each country’s contribution to Rather than considering the way personal way,” Perth delegate as inequality, poverty, climate the United Nation’s Sustainable SDGs are being implemented in Karen Wilson said. -

MGS Masteroppgave Silje Sævareid Kleiveland.Pdf (324.7Kb)

A Qualitative Study A Journey Towards Hillsong Church A Norwegian Story Silje Sævareid Kleiveland VID vitenskapelige høgskole Stavanger Masteroppgave Master i Global Studies Antall ord: 27869 16.Mai 2018 1 Acknowledgement First, I want to say thank you to Hillsong church, and especially Hillsong Sandnes, where I have spent most of my research time throughout this study. Thank you for letting me join your church and fellowship, and for including me in your «family». Especially thanks to those of you who let me interview you. It was interesting and «lærerikt» to talk to you. And i wouldn’t´t have been able to do the research if if wasn’t´t for you. So thank you! Further, I want to thank my supervisor Stian Sørlie Eriksen who has provided meaningful guidance and inspiration through the process. Thanks to my little sister Camilla and Anette for their help and motivation in stressful times Last, but not at all the least, Erlend. Thank you for always being supportive of me, and backing me up in whatever I chose to do. Thank you for words of wisdom and encouragement. And for making dinner and walking the dog, while I´m working om my thesis. Abstract Hillsong Norway, which have congregations in several of the larger cities in Norway. Hillsong Norway quite recently formally established through incorporation of an already existing comparable locally grown church network. Based on qualitative studies and fieldwork in both churches, the thesis discusses how individuals and congregations come to see themselves as part of a global church and how this relates to individual and congregational identity. -

The Institution, the Ethic, and the Affect: the Hillsong Church and The

The Institution, the Ethic, and the Affect: The Hillsong Church and the Production of Multiple Affinities of the Self Submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Bachelor of Arts & Commerce, with Honours in Sociology College of Arts & Social Sciences, Australian National University Matthew Wade 2010 1 Unless otherwise acknowledged in the text, this thesis represents the original research of the author: Signed:………………………… Matthew Wade 2 Acknowledgments I would like to express the greatest of thanks to my Honours supervisor, Dr Maria Hynes. Dr Hynes’ relentless positivity, gentle encouragement, and of course brilliant insight were absolutely invaluable. Warm thanks also go to Dr Rachel Bloul and Dr Joanna Sikora for their guidance, as well as my fellow classmates. Lastly, I give guarded thanks to the Hillsong Church, an institution that at once is endlessly fascinating, inspiring, and unnerving. 3 Abstract The Hillsong Church, based in Sydney, is the Australian exemplar of the ‘megachurch’ phenomena, characterised by large, generally non- denominational churches with evangelical, ‘seeker-friendly’ aspirations and adoption of contemporary worship methods. Given the increasingly large following the Church commands, there is surprisingly little scholarly research on Hillsong, particularly from the perspective of Sociology. This study seeks to contribute to a sociological understanding of the phenomenon of Hillsong by analysing the particular ways that its doctrine and practices evoke and respond to crises of the self in modernity. Hillsong does not rail against the developments associated with modernity, rather, the Church consciously evangelises in recognition of them, managing to both empower the individual and also act as a bulwark against more dehumanising elements of modern society. -

1 Australasian Pentecostal Studies 13 (2010) Issue 13 (2010)

1 Australasian Pentecostal Studies 13 (2010) Issue 13 (2010) 2 Australasian Pentecostal Studies 13 (2010) Australasian Pentecostal Studies Editor: Shane Clifton, Alphacrucis College Editorial Advisory Board Individual articles, ©2010, APS and the contributors. John Capper, Jacqueline Grey, Tabor College (Victoria) Alphacrucis College Mark Hutchinson, Matthew Del Nevo, University of Western Sydney Catholic Institute of Sydney All copyright entitlements are retained for the electronic and other ver- sions of the contents of this journal. Note: The opinions expressed in articles published in Australasian Pente- costal Studies do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the editor and edi- torial advisory board. Australasian Pentecostal Studies is a peer refereed scholarly journal, type- set on Adobe InDesign CS4. Material for publication should be submitted to: The Editor, Australasian Pentecostal Studies, PO Box 125, Chester Hill 2162, Australia, Fax: +61-2-96459099; Email: [email protected]. Australasian Pentecostal Studies appears annually and in special additions as may occasionally occur. The costs of the journal are underwritten by the generous sponsorship of Alphacrucis College, as well as subscriptions as follows: Aust & NZ Rest of World Institution: AUS$40.00 US$40.00. Individual: AUS$30.00 US$30.00 Student: AUS$20.00 US$20.00 The Journal may be accessed by over the net, at http:// webjournals.alphacrucis.edu.au/ ISSN 1440-1991 Cover design, Elly Clifton 3 Australasian Pentecostal Studies 13 (2010) Contents Articles. 7. Stephen G. Fogarty, ‗The Dark Side of Charismatic Leadership‘. 21. Julien M. Ogereau, ‗Paul‘s Leadership Ethos in 2 Cor 10–13: A Critique of 21st Century Pentecostal Leadership‘. -

Guests of Pastors Brian and Bobbie Houston Hillsong Conference

GUESTS OF PASTORS BRIAN AND BOBBIE HOUSTON HILLSONG CONFERENCE Sydney Information Tuesday July 10 – Friday July 13, 2018 REGISTRATION INFORMATION For each person attending Hillsong Conference we will require a guest registration to be filled out through the link HERE. Please advise Jess Irwin ([email protected]) if you have previously registered so we can correctly allocate you to guest seating. Your guest pass will be posted to you prior to conference and we kindly ask you to bring this with you to conference. You will receive a guest pack from our team on arrival with any additional information you may need. Our guest relations team will continue to be in contact with you in the lead up to conference to ensure you have everything you need, however please feel free to contact us if you have any questions. LOCATION Qudos Bank Arena - Corner of Olympic Boulevard & Edwin Flack Avenue, Sydney Olympic Park NSW 2127. SCHEDULE For your general information, the schedule for Hillsong Conference 2018 begins with a night rally on the Tuesday evening of conference. From Wednesday – Friday of conference, each day will start with a morning rally with a break in the afternoon and a night rally again in the evening. Please continue to check the Hillsong Conference web page for updated program information at: https://hillsong.com/conference/sydney/program-2018/ HILLSONG LEADERSHIP NETWORK LUNCHEON Pastors Brian and Bobbie will be hosting a Hillsong Leadership Network luncheon on Tuesday, July 10 (prior to the commencement of conference). This gathering is a key focus and always an incredible time for connection. -

Worshipping Bodies: Affective Labour in the Hillsong Church

bs_bs_banner Worshipping Bodies: Affective Labour in the Hillsong Church MATTHEW WADE* and MARIA HYNES Sociology, Australian National University, Building 22, Acton Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Received 1 February 2012; Revised 31 May 2012; Accepted 31 July 2012 Abstract The Australian megachurch, Hillsong, is as well known for its music and spec- tacle as it is for the content of its religious ideas. This is largely due, as Connell argues in his geography of Hillsong, to the peculiar mix of the theological and the modern that a highly globalised and mediatised context can today produce. This paper re-examines the phenomenon of Hillsong through the theory of affect, which has gained notable analytical purchase in geography in recent years. More specifically, it uses the concept of ‘affective labour’ to analyse the specific ways in which bodies are put to work in the spaces of Hillsong worship. We demon- strate the way that Hillsong produces and mobilises affect in order to attain the collective experience of the spectacle, which is so crucial to Hillsong’s visibility as a social phenomenon and also to its recruitment of the individual member into the logic and ethos of the church as a whole. We indicate the importance for the success of Hillsong of producing particular kinds of subject, namely, subjects who are at once comfortable, enthusiastic and loyal. By recruiting its followers as affective labourers towards a shared evangelical cause, the embodied and vaguely felt sense of potential of members is mobilised towards the spectacular phenom- enon that is the Hillsong church. -

Hillsong Church

Hillsong Church Religion Media Centre Collaboration House, 77-79 Charlotte Street, London W1T 4LP | [email protected] Charity registration number: 1169562 Hillsong Church is an Australian Evangelical “mega church” with branches in 23 countries worldwide, including the UK. It is a Pentecostal Church affiliated with the largest Pentecostal movement in Australia, Australian Christian Churches, previously called the Assemblies of God in Australia. It is known for its original music under the three labels / groups: Hillsong Worship, Hillsong United and Young and Free. Under these labels, Hillsong has produced 66 albums. Hillsong claims to have a weekly global attendance of 130,000. HISTORY Hillsong Church has its origins in the leadership of Pastor Frank Houston (1922-2004), father of the current leader, Brian Houston (born 1954). Frank Houston, a New Zealander, served as superintendent of the Assemblies of God in New Zealand from 1965 to 1971. In 1977, Houston moved to Sydney and founded his own church, known as the Sydney Christian Life Centre. Affiliated churches were quickly established. Brian joined the church network in 1978 and was leading his own congregations from 1980. In 1983, Brian, with his wife Bobbie, founded Hills Christian Life Centre, and the associated music label, Hillsong, in the Hills District of Sydney, Australia. Affiliated churches were established through the 1980s and 1990s, and spread to other countries. The London church was formed in 1992. In 2000, Brian and Bobbie merged the Christian Life Centre churches under the new name of Hillsong Church, partly because of the success of the music label. 1 “Hillsong Church” BELIEFS AND PRACTICES Hillsong subscribes to the belief statement of the Australian Christian Churches – described as “Bible-loving, evangelical and Pentecostal, and are about connecting people to Jesus Christ.” The Bible is taken as “God’s word” and as authoritative. -

Your Alpha Australia Annual Report 2019 500,000 Guests… with Your Support We Can Double It

Your Alpha Australia Annual Report 2019 500,000 guests… with your support we can double it Thousands of Australians continue to answer the call of the Great Commission around the clock face of every part of the Church, Melinda Dwight faith. Hasn’t it been great to sharing around tables and see banners across Australia exploring faith together. Alpha Australia National drawing the attention of Director We are so grateful for the passers-by? All glory and generosity of all who give, @melindadwight thanks to God who has serve, pray, volunteer and prompted by the Holy Spirit invite, so that each of these What an amazing year! 500,000 to be Alpha guests. stories is made possible. We’ve loved celebrating Together we are seeking with you that through local All of us still know friends to make Jesus’ great churches running Alpha that haven’t come to faith. commision our first priority. 500,000 Australians have God cares about each of heard about the good them and so do we. Every Thank you for being hope news of Jesus. Great work person matters. Every story bearers and facilitating everyone! is important. Together let’s change in the faith climate facilitate another 500,000 to in Australia. Please keep Together there’s been participate in Alpha. praying that we can serve much prayer for people to many more people through explore faith, and many Thank you for your powerful Alpha and together see His conversations that have partnership in the Gospel. kingdom come. lead to invitations, and in As you can see in this some cases, acceptances. -

A Ministry of Teaching November/December 2003 Australia

Australia A Ministry of Teaching But strong meat belongeth to them that are of full age...to discern (diakrisis) both good and evil (Heb. 5:14) Whom shall He teach knowledge? and whom shall He make to understand doctrine?... (Is.28:9) Newsletter of TA Ministries Vol.2, No.25 November/December 2003 PO Box 1499, Hervey Bay, Qld, 4655 Editors Comment Australia Is the church today becoming more God focused or man focused? We Ph. 0411489472 (Mob.) Fax (07)41240915 would contend strongly that the church today is increasingly becoming self Website:http://taministries.cjb.net/ oriented in doctrine, behaviour and in worship. E-mail: [email protected] In the teaching of the doctrine of salvation it is not hard to see todays emphasis is on man...just ask Christians these questions: Does man seek or TA Ministries is a non-denominational non choose God for salvation? (No: Rom.3:11; Jn.1:11-13)...or does God choose profit faith ministry, teaching, informing and man? (Yes: Eph.1:4; Lk.19:10; Jn.15:16). The gifts - are they to edify self? equipping the church. (No: Rom.15:1-3; 1Cor.14:17)...or are they for the edification of the church to glorify God? (Yes: Eph.4:11,12; Rom.14:19; 1Thess.5:11; 1Cor.14:5,12,26). Editor: Terry Arnold (Dip. Bib. & Min., Dip. Methods of evangelism tend to indicate the doctrine used. Modern methods Teaching, Author.) increasingly highlight our lack of trust in the Gospel as the ‘power of God unto salvation’.