1 Australasian Pentecostal Studies 13 (2010) Issue 13 (2010)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

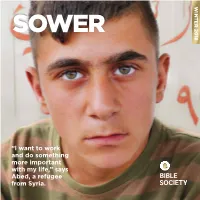

“I Want to Work and Do Something More Important with My Life,” Says Abed, a Refugee from Syria

WINTER 2018 SOWER “I want to work and do something more important with my life,” says Abed, a refugee from Syria. 1 A lamp to their feet A light to their path For long-time Bible Society the Flying Bible Man, who became chaplain to construction workers supporters Bill and Jocelyn Ross, a great asset. on a dam, Trevor Booth went the Bible really has proved to be “I’d go with Trevor in his plane with him to visit the workers. “He “a lamp to their feet and a light to and catch up with people on the had a good fi lm to show in the their path,” as they have navigated stations. I was fl ying with Trevor workmen’s mess service. On one the roads God has taken them. when the Bible Society made a occasion the sound system wasn’t After studying and marrying fi lm about his work in the East working – but it didn’t matter, in Canberra, Bill and Jocelyn Pilbara. What I remember the because Trevor narrated the fi lm! ministered for a few years in most about the fi lming was the He had shown the fi lm so many Albury, NSW, before moving to constant fl ies in our eyes! ... it was times, he knew the dialogue by the far north of Western Australia a wonderful experience” heart.” in 1970 and beginning a life-long When the Rosses moved to Trevor also assisted with the ministry there. Dampier, a Pilbara port town, Bill They began in the town of again engaged in patrols with Kununurra and the patrol district Trevor at several stations in the of the East Kimberley, with the West Pilbara, and Barrow Island. -

AFB Hosts Historic Management Conference

PR9000 The Blakemore Way_Newspaper February 2012_A3 24/01/2012 17:42 Page 1 February 2012 Management pecial Conference S The Newspaper for Employees of A.F. Blakemore & Son Ltd. To grow a family business AFB Hosts Historic in ways that are profitable Integration and sustainable for the benefit of our staff, Leads to Further customers and community. Management Name Changes Three divisions of the “Blakemore Retail Conference enlarged A.F. Blakemore combines two companies group of companies are to with a great heritage. We The ongoing integration process with Capper & Co and the role that this be rebranded as part of have an exciting future the integration process ahead of us and with our will play in generating sustainable growth were the key topics discussed with Capper & Co. first class management team and support staff we The Tates & Waynes at this year’s A.F. Blakemore Management Conference. make one great company. division of A.F. Blakemore The conference represented “We have a wonderful operation to create “best in Haigh, who presented his & Son Ltd has been "Our job for the future is an historic moment for A.F. opportunity with Capper & Co sector service”. vision for the future of retail rebranded as Blakemore to continue with the Retail following the integration to ensure that Blakemore with almost 300 and massive benefits are A.F. Blakemore’s support for development. merger of the two stores Blakemore Retail really is managers from across A.F. already being achieved as a small regional producers Peter Blakemore thanked his Blakemore and Capper & Co result of the merger.” groups in March 2011. -

IDEOLOGY Second Mrican Writers' Conference Stockh01m1986

IDEOLOGY Second Mrican Writers' Conference Stockh01m1986 Edited by with an lin"Coductory essay by Kii-sten B-olst Peitersen Per W&stbei-g Seminar Proceedings No. 28 Scandinavian Institute of African Studjes Seminar Proceedings No. 20 CRITICISM AND IDEOLOGY Second African Writers9 Conference Stockholm 1986 Edited by Kirsten Holst Petersen with an introductory essay by Per Wastberg Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, Uppsala 1988 Cover: "Nairobi City Centre", painting by Ancent Soi, Kenya, reproduced with the permission of Gunter PCus. ISSN 0281 -00 18 ISBN 91-7106-276-9 @ Nordiska afrikainstitutet, 1988 Phototypesetting by Textgruppen i Uppsala AB Printed in Sweden by Bohuslaningens Boktryckeri AB, Uddevalla 1988 Foreword The first Stockholm conference for African writers was held in 1967, at Hasselby Castle outside Stockholm, to discuss the role of the writer in mo- dern African Society, especially the relationship of his or her individuality to a wider social commitment. It was arranged on the initiative of Per Wastberg, well-known for having introduced much of African literature to the Swedish public. On Per Wastberg's initiative the Second Stockholm Conference for Afri- can Writers was arranged almost twenty years later. This time the Scandi- navian Institute of African Studies was again privileged to arrange the con- ference in cooperation with the Swedish Institute. We extend our gratitude to the Swedish Institute, the Swedish Interna- tional Development Authority (SIDA), and the Ministry for Foreign Af- fairs for generous financial support. We wish to thank our former Danish researcher Kirsten Holst Petersen for her skilful work in arranging the con- ference and editing this book. -

Thank a Veteran on Veterans Day Wednesday, Nov

VETERANS DAY SALUTE Thank a veteran on Veterans Day Wednesday, Nov. 11 SECTION C | THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 2020 THE NEWS Vernon “Bud” F. Adam Charles E. Allen Emmett Allen Gilbert Leroy Allen Harvey Lee Allen John Allen Marlin (Hoddy) Allen Cpl. SP3 Army, Tec 5 SrA Air Force US Navy US Marine Corps 7TH Regiment of Marines, Sgt, WWII July 22, 1954 - 1941 - 1945 1st Class WWII WWII Indiana Rifles 1942 - 1946 June 21, 1956 Okinawa and Guam. Served in the War of 1812 South Pacific Fought in the Korean War. SSG Elaine M. Anderson John R. Allensworth Rex Allensworth Dennis Altenhofen Ronald Altenhofen Army WAC Sept. 1966 - 1969 Andrew Armbruster Bernard Armbruster US Air Force US Navy US Navy US Army Army Reserves Vietnam WWII 1961 - 1963 A2C 1944 - 1946 EM3 Spec 4 Sept. 1974 - April 1995 Navy Army USS Hornet CVA12 Korea, KMAG Army Commendation Medal, 1964-1966 1955 - 1958 1960 - 1962 Good Conduct Medal, Army Achievement Medal Dennis Arps Claude Armbruster Gerald Armbruster Leo Armbruster Phil Armbruster Richard Armbruster SP4 US Army, Military Robert F. Baldwin WWII WWII WWII Vietnam Purple Heart - France Police, D Batter, 5th Lt. Col. US Army Army Army Army Army WWII Battalion 6th Air Defense 1994 - 2010 1968-1970 Army and 284th MP Company, 709th MP Battalion Frankfurt, West Germany WELLMAN KEOTA KALONA WILLIAMSBURG NORTH ENGLISH SIGOURNEY MT. PLEASANT Back row: Charles Yoder, Lyle Donald, Mellissa Zuber, Jared Powell, Kenton Doehrmann, and Bowen Yoder; Contact us for your pre-planning & funeral services front row: Brittni Kiefer, Kimberly Powell-Doehrmann, Jacque Powell, and Samantha Lown. -

Annual Report Two Thousand & Fourteen Hillsong Church, Australia Hillsong Church Annual Report 2 Index

Annual Report Two Thousand & Fourteen Hillsong Church, Australia 2 Annual Report Hillsong Church Index Chairperson’s Report 4 The Church I Now See 5 Lead Pastor’s Report 6 General Manager’s Report 7 History 8 Church Services 10 Programs & Services 12 Children 14 Youth 16 Women 18 Young at Heart 20 Pastoral Care 22 Volunteers 24 Creative Arts 26 Worship 28 Conferences 30 Missions 32 Education 34 Local Community Services 36 Overseas Aid & Development 42 The Hillsong Foundation 46 Two Thousand & Fourteen Two Our Board 48 Financial Reports 51 “I see a church Governance 58 that beckons WELCOME HOME to every man, woman and child that walks through the doors.” – Brian Houston (The Church I Now See) 3 Chairperson’s Report Brian & Bobbie Houston As we reflect on the year past, we can truly thank God for His We have now been holding Hillsong Conference since 1986 unwavering goodness and love for humanity. God specialises with the mission: Championing the cause of local churches in lifting people out of tragedy and pain, rebuilding hope and everywhere. With over 22,000 attendees and 19 Christian restoring us to a friendship with Him. denominations represented we celebrate the diversity of the expressions of our faith and gather around the common We as a church are privileged to play our role in seeing lives understanding that a healthy local church can make a positive impacted through the Gospel of Jesus Christ. At Hillsong impact in its community. Church, hundreds of people make a decision to follow Christ each week, a foundational step on a journey of personal It is with this understanding we are enthusiastic about freedom and understanding. -

A Theology of Possessions in the African Context: a Critical Survey

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UWC Theses and Dissertations UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE Thesis for MTh. Degree John Hugo Fischer Student Number: 2530178 Department of religion and theology Title of thesis A Theology of Possessions in the African context: A critical survey Supervisor: Prof. Ernst Conradie Date November 2007 1 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magister Theologae in the Department of Religion and Theology at the Faculty of Arts at the University of the Western Cape By John Hugo Fischer Supervisor: Professor E. M. Conradie November 2007 2 Keywords Possessions Africa Christianity Worldviews Consumerism Private Property Communal Possessions Urbanization Stewardship Vineyard Missions 3 Abstract This thesis has been researched against the back drop of conflict that had arisen due to different approaches to possessions in the African church as practiced within the Association of Vineyard Churches. This conflict arose because of diff erent cultural approaches to possessions and property rights as they affect different parts of the African church. In order to analyse this conflict and arrive at some understanding of the different forces operating in the area of resources and possessions it was necessary to adopt the approach laid out below. The objective was to arrive at an analysis of such differences, and the sources from which such differences originated, and then to draw some conclusion with regard to the present state of the debate on possessions and how this could affect the praxis of the Vineyard churches in Sub Saharan Africa in which I serve. -

February 2004

VOLUME 31/1 FEBRUARY 2004 “Do you not give the horse his strength or clothe his neck with a flowing mane?” Job 39:19 faith in focus Volume 31/1, February 2004 CONTENTS Editorial Whose party are you going to? Uncovering a very present danger 3 It was some years ago that a minister was overhearing several colleagues at a minister’s conference speaking about several high-powered revival meetings Not satisfied with Jesus? When faith is not alone 7 they had experienced. They spoke in glowing terms of how warmly they felt and how much everyone there shared a wonderful spiritual unity. Sons of encouragement 8 This minister shared with them his own experience of a meeting he had come World News 9 from the night before he flew over. He detailed the feelings he had when over Breakthrough 40,000 sang the same songs, held hands, and came away with a truly The lesson in life 11 unforgetable event. Missions in focus His colleagues now were completely captivated by his story. This was something Growing the church in Karamoja extraordinary. And to hear all this from this man who otherwise you would think Prayer points RCNZ food aid to Malawi 12 was the last to be open to such a move of the Spirit! They had to ask him who was the cause for this incredible time. Which special person’s meeting was it? Surfing the Net The upside & downside of the Internet 15 “Oh,” the minister replied, “it was a Paul McCartney concert.” Naturally, those ministers felt somewhat taken in. -

BAOR July 1989

BAOR ORDER OF BATTLE JULY 1989 “But Pardon, and Gentles all, The flat unraised spirits that have dared On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth So great an object….” Chorus, Henry V Act 1, Prologue This document began over five years ago from my frustration in the lack of information (or just plain wrong information) regarding the British Army of The Rhine in general and the late Cold War in particular. The more I researched through books, correspondence, and through direct questions to several “Old & Bold” on Regimental Association Forums, the more I became determined to fill in this gap. The results are what you see in the following pages. Before I begin a list of acknowledgements let me recognize my two co-authors, for this is as much their work as well as mine. “PM” was instrumental in sharing his research on the support Corps, did countless hours of legwork, and never failed to dig up information on some of my arcane questions. “John” made me “THINK” British Army! He has been an inspiration; a large part of this work would have not been possible without him. He added the maps and the color formation signs, as well as reformatting the whole document. I can only humbly say that these two gentlemen deserve any and all accolades as a result of this document. Though we have put much work into this document it is far from finished. Anyone who would like to contribute information of their time in BAOR or sources please contact me at [email protected]. The document will be updated with new information periodically. -

Love Your Global Neighbour

theadvocate.tv DECEMBER 2018 IN CONVERSATION Finding Faith duo, Andrew Tierney “Perhaps we need to keep challenging ourselves about the and Tim Dunfield talk about their passion for writing power of un-deciding to open ourselves to an even bigger songs of worship and their debut album. PAGE 12 >> decision – an even bigger ‘yes’.” SIMON ELLIOTT PAGE 13>> 3 Holy secularism Christmas is not what it used to be >> 4 Royal Commission Scheme provides support for childhood abuse >> Photo: Shane Burrell Risanya can grow enough food to feed her family and sell at the market for an income, thanks to the support of good neighbours in Australia. Love your global 10 Asia Bibi freed Christian mother released neighbour from Pakistan’s death row >> Baptist World Aid Australia, in conjunction with A Just Cause, has launched a efforts leading up to the next new report: The Global Neighbour Index. The report examines: Is Australia a good Federal Election, where Baptists global neighbour?, taking seriously Jesus’ call to “love your neighbour as yourself”. around the country will organise electorate forums using the report as a guide to converse Committed to Against its most-developed peers, government and the broader “It is not often that we get to with candidates. Australia was ranked 11th out of community to participate influence the policymakers of The index uses ten indicators being honest, 20 overall in a report that graded responsibly in seeking change. our nation in such a specific and to consider complex issues such transparent and each country’s contribution to Rather than considering the way personal way,” Perth delegate as inequality, poverty, climate the United Nation’s Sustainable SDGs are being implemented in Karen Wilson said. -

The Roots of African Theology

with the Vatican than with Protestant evangelicals. We should be If we should miss or dismiss the promise and the presence grateful for the many contacts between the WCC and the Roman of the crucified and risen Lord in the continuation of missionary Catholic Church during and after Vatican Council II, but it is likely work, our task would be a lost cause, a meaningless enterprise. that the official trend in the Vatican in the 1990s will continue We would make concessions to the professional pessimists who more in the direction of counter-reformation than co-reformation. think it is their task to spread alarm and defeatism. But within We should certainly continue official contacts with the Vatican, the light of the Lord's promise and presence, the continuation of but on the national, regional, and continental levels we should the church's mission in the last decade of this century will not strengthen our relations with those groups within the Roman be a lost cause or a meaningless enterprise, since we know that Catholic Church that, in spite of heavy pressure from the Vatican, in the Lord our labor cannot be in vain. are still moving in the direction of a co-reformation. Mission in the 1990s needs Christians and churches that work in the spirit of the document "Mission and Evangelism: An Notes ---------------- Ecumenical Affirmation." Our task now is to put flesh on the spirit of that document, in our words and deeds. 1. Harvey Cox, "Many Mansions or One Way? The Crisis in Interfaith Dialogue," Christian Century, August 17-24, 1988, pp. -

The Royal Engineers Journal

-- VOL. LXVI. No. 2 JUNE, 1952 THE ROYAL ENGINEERS JOURNAL CONTENTS The History of Early British Military Aeronautics Brigadier P.W. L. Broke-Smith WS5 The Haifa-Beirut-Tripoli Railway . Major D. H. Eakins 922 Royal Engineer Officer Training . Captain F.W. E. Fursdon 142 Soil Stabilization . Colonel E.W. L.Whitehorn 156 Demolitions and Minelaying-Some German Methods Major M. L. Crosthwait #7i Duffer's Oued . "The Duffer" 180 Beach Clearance Party . Sapper Jack " 186 Memoirs, Book Reviews, Technical Notes . 193 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY THE INSTITUTION OF ROYAL ENGINEERS CBHAT'HAM*.------ KENIT1`- --- ...- lA-n-. ~-.--- ~""''L^^ INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY AGEN AM DO NOT REMOVE 0 - CEMENTATION * for saling water lwka, arresting settlement of structures, remedying deterioration of concrete or masonry works. G U N I T E: for reconditioning defective concrete stnc- tures, encasing structural steelwork, lining tunnels, water reservoirs and other works. FO U N D A T IO N S: underpinning of damaged proprty presents little difficulty if F R A X CO IS BORED PILES are used. COMPANY LIMITED BENTLEY WORKS, DONCASTER Tel. DON 54177--9 i THE PRINTERS OF THIS JOURNAL Mackays of Chatham will be pleased to receive your enquiries and orders for Printing, Bookbinding and Blockmaking I Phone CaATHAM 2243 W. &J. MACKAY & Co. LTD. FAIR ROW, CHATHAM ADVERTISEMENTS i O 0S Ll- 8& u g z > O 0Sai o *uLU c0 xx u O'jS 5. 0 ". ' [0 I o, flr cl O ce ' 0 "OI - TH -CA CY Brook House, 113 Park Lane, London, W.1. ii ADVERTISEMENTS By Appointment Makers of Weatherproof Clothing to His Late Majesty King George VI Burberry Hacking Jacket with slant side pockets. -

Ubuntu: the Contribution of a Representative Indigenous African Ethics to Global Bioethics Leonard T

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 2012 Interpreting the Culture of Ubuntu: The Contribution of a Representative Indigenous African Ethics to Global Bioethics Leonard T. Chuwa Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Chuwa, L. (2012). Interpreting the Culture of Ubuntu: The onC tribution of a Representative Indigenous African Ethics to Global Bioethics (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/408 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERPRETING THE CULTURE OF UBUNTU: THE CONTRIBUTION OF A REPRESENTATIVE INDIGENOUS AFRICAN ETHICS TO GLOBAL BIOETHICS A Dissertation Submitted to the Center for Healthcare Ethics McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Leonard Tumaini Chuwa, A.J., M. A. December, 2012 Copyright by Leonard Tumaini Chuwa, A.J., M.A. 2012 INTERPRETING THE CULTURE OF UBUNTU: THE CONTRIBUTION OF A REPRESENTATIVE INDIGENOUS AFRICAN ETHICS TO GLOBAL BIOETHICS By Leonard Tumaini Chuwa, A.J., M.A. Approved ______________________________________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Gerard Magill, Ph.D. Henk ten Have, M.D., Ph.D. Professor of Healthcare Ethics Director, Center for Healthcare Ethics The Vernon F. Gallagher Chair of the Professor of Healthcare Ethics Integration of Science, Theology, (Committee member) Philosophy and Law (Dissertation Director) ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Aaron L.